Priest-King (sculpture)

| Priest-King | |

|---|---|

The Priest King | |

| Artist | unknown, prehistoric |

| Year | c. 2000–1900 BCE |

| Type | fired steatite |

| Dimensions | 17.5 cm × 11 cm (6.9 in × 4.3 in ) |

| Location | National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi |

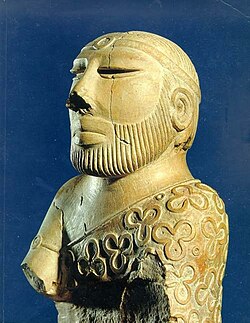

The Priest-King, in Pakistan often King-Priest,[1] is a small male figure sculpted in steatite found during the excavation of the ruined Bronze Age city of Mohenjo-daro in Sindh, now Pakistan, in 1925–26. It is dated to around 2000–1900 BCE, in Mohenjo-daro's Late Period, and is "the most famous stone sculpture" of the Indus Valley civilization ("IVC").[2] It is now in the collection of the National Museum of Pakistan as NMP 50-852. It is widely admired, as "the sculptor combined naturalistic detail with stylized forms to create a powerful image that appears much bigger than it actually is,"[3] and excepting possibly the Pashupati Seal, "nothing has come to symbolize the Indus Civilization better."[4]

The sculpture shows a neatly bearded man with a fillet around his head, possibly all that is left of a once-elaborate hairstyle or headdress; his hair is combed back. He wears an armband, and a cloak with drilled trefoil, single circle and double circle motifs, which show traces of red. His eyes might have originally been inlaid.[5] The sculpture is incomplete, broken off at the bottom, and possibly unfinished. Originally it was presumably larger and probably was a full-length seated or kneeling figure.[6] As it is now, it is 17.5 centimetres (6.9 in) high.[7]

Though the name Priest-King is now generally used, it is highly speculative, and "without foundation".[8] Ernest J. H. Mackay, the archaeologist leading the excavations at the site when the piece was found, thought it might represent a "priest". Sir John Marshall, head of the pre-Partition Archaeological Survey of India ("ASI") at the time, regarded it as possibly a "king-priest", but it appears to have been his successor, Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who was the first to use Priest-King.[9] An alternative designation for this and a few other IVC male figure sculptures is that they "are commemorative figures of clan leaders or ancestral figures".[3]

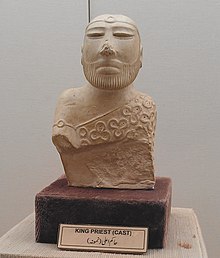

A replica is normally displayed at the National Museum of Pakistan, while the original is kept secure. Mr. Bukhari, the director of the museum explained in 2015 "It's a national symbol. We can't take risks with it".[10] The Urdu language title used by the museum (with the English "King-Priest") is not an exact translation, but حاکم اعلی (hakim aala), a well-known expression in Urdu-Persian-Arabic meaning a sovereign or bishop (who is entitled to sit in a chair of state on ceremonial occasions).

Description

[edit]

The statuette is carved in the soft mineral of steatite, and (despite being apparently unfinished) has been fired or baked at over 1000 °C to harden it. The long crack running down the right hand side of the face, already present when it was excavated, may have been caused by this, or by a later shock. There is an uneven break at the bottom of the piece, with the patterned robe continuing further down at the back than the front. The nose is also damaged at the tip, but many other areas are in good condition. It has been compared to other IVC male figures, more fully complete, which show a seated position, with in some cases one raised knee and the other leg tucked beneath the body. The Priest-King may have originally had this shape.[11] Some archaeologists, including Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, believe that this and other statues were "broken and defaced" deliberately, as their subjects lost their prestige.[12]

The eyes are wide but narrow, apparently half-closed; there were probably inlaid pieces of shell or stone representing the pupils.[13] The ears are very simply shaped, as on some other stone heads from the site. The back of the top of the head is flat, probably so that something now missing could be attached, and there are various theories as whether it was a carved "bun" or a more elaborate headdress, perhaps in other materials and only worn at times. Two holes below the ears may have been for attaching this, or perhaps a necklace. Mackay suggested the flattening was because the head was damaged, which few later writers agree with. Another possibility is that it was designed to fit into a niche with a sloping top.[14]

The figure wears a toga-like outer garment that only covers one shoulder, with a pattern of trefoils; Pakistani sources like to suggest this is in the local ajrak technique of block-printing. The interiors of the raised trefoil and other shapes on this were originally filled with a red material, probably some type of paste. The interiors of the shapes were left rough, to help this adhere. The space around the shapes showed traces, at the time of the original excavation, of a material which by then was "blackish" but may originally have given a green or blue background to the relief shapes.[15]

Marshall's first thoughts on the IVC had been that the links with Mesopotamia had been very close, and his preliminary reports, up to 1926, called it the "Indo-Sumerian Civilization". He then realized this was wrong, and started to use "Indus Civilization".[16] There has been much discussion of the possible relationship between the Priest-King and somewhat similar Mesopotamian figures. The art historian Benjamin Rowland concluded that "the plastic conception of the head in hard, mask-like planes and certain other technical details are fairly close, and yet not close enough to prove a real relationship".[17]

According to Gregory Possehl, it is the treatment of the facial hair in particular that suggests the figure was not fully finished. While the main beard is carefully worked with parallel lines, the upper lip is also raised above the level of the surrounding flesh, but no lines have been added to show moustache hair; it is simply smooth. On the cheeks the lines for the beard continue more faintly onto the cheek, which in a finished piece would probably have been smoothed away.[9]

Possible support for interpreting the figure as a religious person are the apparent representation of the eyes as fixed on the tip of his nose, a practice in yoga, and the similarity of the robe worn over one shoulder to later garments, including the Buddhist saṃghāti.[17] The focus on the tip of the nose was noticed by one of Marshall's Indian assistants, and Marshall saw the same feature in the Pashupati seal.[18]

Excavation and recent history

[edit]

The sculpture was found at a depth of 1.37 metres by the archaeologist Kashinath Narayan Dikshit (later head of the ASI) in the "D-K B" area of the city, and given the find number DK-1909. The precise findspot was "a small enclosure with some curious parallel walls", possibly the hypocaust for a hammam or sauna. The sculpture was found in a small passage between two of these walls, but this seems unlikely as its normal position, and it is thought that it fell or rolled into this space as the city fell into ruin.[7]

The finds from Mohenjo-daro were first sent to the Lahore Museum, but later transferred to New Delhi, the new capital of British India, and the headquarters of the ASI, with a view to displaying them in the "Central Imperial Museum" that was planned. Eventually, after the partition of India in 1947, this was established as the National Museum of India. The new Pakistani heritage authorities requested the return of the IVC artefacts, as almost all of those found by the time of independence had come from sites, like Mohenjo-daro, that were now in Pakistan.[19]

The statue was only returned to Pakistan after the 1972 Simla Agreement between Pakistan and India, represented by their heads of government, respectively Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, the President of Pakistan, and Indira Gandhi, the Prime Minister of India. According to a Pakistani archaeologist, Gandhi refused to return both the Priest-King and the other most iconic Indus sculpture, the Dancing Girl, a smaller bronze sculpture also found at Mohenjo-daro, and told Bhutto he could only choose one of them.[20]

The statue was exhibited in London at the exhibition of "The Art of India" at the Burlington Fine Arts Club in 1931 (Cat. 114), as was the Dancing Girl (Cat. 136).[21] This first display of IVC finds outside India attracted considerable notice in the press.[22] Other exhibitions include "Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus" in 2003, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Cat. 272a).[3] Replicas of the statue are popular in Pakistan and beyond,[23] and a replica that is much larger than the original has been erected at the entrance to the Mohenjo-daro site.

Context

[edit]Art

[edit]

The statue is one of the "seven principal pieces of human sculpture from Mohenjo-daro".[25] The others include two small full-length nude bronze female figures, both called "dancer"s by some, but alternative activities have been suggested, such as carrying offerings.[26] There are also three male heads in limestone or alabaster, apparently broken-off, and the headless figure of a Seated Man. Various points of contrast and comparison between these pieces and the Priest-King have been proposed; there is a considerable variety in the depiction of details among them.[27] The headless seated man may show the pose of the missing lower part of the Priest-King.[28] Very likely sculpture existed in wood, but none has survived.[29]

There are also very numerous small and simple terracotta figures from all over the IVC, most female, generally similar to those produced over much of India later, indeed up to the present day. Elaborate headdresses are a notable feature of these.[30]

Steatite was widely used in the IVC; in one technique it was ground into a paste, and then fired to make decorated beads, many of which were exported. It was also the main material used for carving Indus seals, sometimes fired and sometimes not; many were carved then given a coating which was lightly fired.[31]

Because of some similarities with art from there, some scholars have suggested that the Priest-King and the handful of similar pieces found in IVC contexts may draw on traditions from further north, especially the contemporary culture known as the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex ("BMAC"). Possibly the pieces were made for people from further north living in IVC cities.[32] Unlike the IVC, the BMAC left some rich graves suggesting a considerable degree of social differentiation,[33] and the large settlements excavated so far each centre on a large fortified complex. These were previously described as "temples", but were perhaps more likely the residence of a local ruler.[34]

IVC politics

[edit]The absence of evidence of a powerful ruling class, despite abundant evidence of highly complex social organization, was one of the most striking aspects of the IVC cities for early excavators, and clear evidence in the usual forms of grand tombs and palaces remains lacking. Whether a ruling class was necessary in Bronze Age conditions to achieve large-scale urbanization remains an unsettled question, also related to the question of whether the IVC was a state, and if so, one state or several. Given the lack of evidence for a military-based monarch or ruling class, the model of some sort of theocracy was widely adopted by the early archaeologists.[35]

This had support from Mesopotamian archaeology, where indeed the earliest cities of Sumer are still thought to have had rulers combining political and religious roles.[36] The British archaeologist Stuart Piggott, who was in India in the 1940s, thought the IVC was "a state ruled by priest-kings, wielding autocratic and absolute power from two main seats of government".[37] Wheeler agreed, and asserted:[38]

It can no longer be doubted that, whatever the source of their authority—and a dominant religious element can fairly be assumed—the lords of Harappa administered their city in a fashion not remote from that of the Priest-Kings or governors of Sumer and Akkad.

Wheeler saw the damage inflicted on the large male figures as deliberate, done during the violent overthrow of the IVC by Aryan invaders that he postulated, an explanation for the end of the IVC that is now generally discredited.[39] In the 21st-century, power in the IVC tends to be seen as more widely spread, perhaps between families or clans, and possibly involving councils, and the decline of the cities as more gradual.[40]

Priest-King figures had also been postulated for the Minoan civilization, which was roughly contemporary with the IVC, rising and falling a few centuries later, but whose discovery and excavation had been a couple of decades earlier. Like the IVC, this had no readable texts, so archaeologists had only the physical evidence to go on. In contrast to the IVC, a number of large and lavishly decorated "palaces" were extremely evident, but there was an absence of indications as to who, if anyone, had lived in them. The head of the excavations, Sir Arthur Evans, had favoured the idea of a Priest-King, and had so titled a fragmentary relief fresco found at Knossos in 1901. This was even more speculative than Wheeler's doing so for the Mohenjo-daro figure; most scholars now doubt the fragments all come from a single figure at all, and Prince of the Lilies is now the usual title given to Evans's reconstruction.[41] Like Marshall (who had trained under Evans),[42] he used his "priest-king" as the image on the cover of his main book on his excavations.[43]

Notes

[edit]- ^ See for example the museum label illustrated below

- ^ Kenoyer, 62 (quoted); Possehl, 114

- ^ a b c Aruz, 385

- ^ Possehl, 114 (quoted)

- ^ Harappa

- ^ Possehl, 114–115

- ^ a b Possehl, 114

- ^ Possehl, 115 (quoted); Aruz, 385; Singh (2008), 178

- ^ a b Possehl, 115

- ^ Shamsie (with quote); Tunio

- ^ Possehl, 115–116; Aruz, 385–388; Kenoyer, 62–63; Harappa

- ^ Kenoyer, 62 (quoted); though in Aruz, 385 Kenoyer is more cautious.

- ^ Several sources say that when the piece was found, one eye had the inlay still in place, though many others say the existence of inlays in the original work is "possible" or "probable"; e.g. Aruz, 385 "may have held inlay".

- ^ Aruz, 385; Possehl, 114–115; Harappa

- ^ Possehl, 114–115; Aruz, 385

- ^ Possehl, 12

- ^ a b Rowland, 34

- ^ Hiltebeitel, A, "The Indus Valley "Proto-Śiva", Reexamined through Reflections on the Goddess, the Buffalo, and the Symbolism of vāhanas", 1978, Anthropos, 73(5/6), 767-797, JSTOR

- ^ Singh (2015), 111–112

- ^ Tunio

- ^ Kumar, who includes a pdf of the full catalogue.

- ^ Kumar; see notes 38 and 39, including quotes from The Times (London) and The Times of India

- ^ Shamsie

- ^ Aruz, Cat #s 272b and 275b are included here.

- ^ Possehl, 113

- ^ Possehl, 113; Kenoyer thinks they carry offerings

- ^ Possehl, 113–117; two of the male pieces have pages on "Harappa" (by Kenoyer); Aruz includes two as Cats. 272b and 277.

- ^ Aruz, 388

- ^ Craven, 24

- ^ Michell, George (2000), Hindu Art and Architecture, 12, 2000, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 9780500203378; Blurton, T. Richard, Hindu Art, 1994, 157-160, British Museum Press, ISBN 0 7141 1442 1; Aruz, 391–392; Clark, Sharri, "Embodying Indus Life", Harappa.com; Craven, 19

- ^ Rowland, 37; Craven, 14

- ^ Aruz, 355, 366; Vidale, 56

- ^ Vidale, 40-42; Aruz, 351

- ^ Aruz, 349-350

- ^ Green; Singh (2008), 176-179

- ^ Possehl, 18; Jacobsen, Thorkild (Ed) (1939),"The Sumerian King List" (Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago; Assyriological Studies, No. 11., 1939)

- ^ Quoted by Possehl, 19; Singh (2008), 176

- ^ Quoted by Possehl, 18

- ^ Humes, 186-187

- ^ Possehl, 57; Green; Singh (2008), 176-179; Aruz, 377

- ^ Beard, 17–21, 23

- ^ Possehl, 10

- ^ Beard, 20

References

[edit]- Aruz, Joan (ed), Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, 2003, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), google books, (relevant IVC catalogue entries by Kenoyer, J.M.)

- Beard, Mary, "Builder of Ruins", in Confronting the Classics: Traditions, Adventures, and Innovations, 2013, Liveright, ISBN 9780871407160, 0871407167, google books

- Craven, Roy C., Indian Art: A Concise History, 1987, Thames & Hudson (Praeger in USA), ISBN 0500201463

- During Caspers, E. C. L., "The 'Priest King' from Moenjo-daro: An Iconographic Assessment", 1985, Annali dell'Istituto Universitario Orientale, vol. 45, issue=1, pp. 19–24, PDF

- Green, A.S. "Killing the Priest-King: Addressing Egalitarianism in the Indus Civilization", Journal of Archaeological Research, volume 29, 153–202, 2021, online

- "Harappa": ""Priest King," Mohenjo-daro" (by Jonathan Mark Kenoyer), Harappa.com. retrieved 6 June 2021

- Humes, Cynthia Ann, "Hindutva, Mythistory, and Pseudoarchaeology", Numen, 59(2/3), 178–201, JSTOR

- Kenoyer, J.M., Heuston, Kimberley Burton, The Ancient South Asian World, 2005, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195222432, 0195222431, google books

- Kumar, Brinda, "“Exciting a Wider Interest in the Art of India”: The 1931 Burlington Fine Arts Club Exhibition", British Art Studies, Issue 13

- Possehl, Gregory A., The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective, 2002, AltaMira Press, ISBN 9780759101722, 0759101728, google books

- Rowland, Benjamin, The Art and Architecture of India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, 1967 (3rd edn.), Pelican History of Art, Penguin, ISBN 0140561021

- Shamsie, Kamila, "The birth of a nation", The Economist 1843 online magazine, 19 January 2015 (log-in required)

- Singh, Kavita, "The Museum Is National", Chapter 4 in: Mathur, Saloni and Singh, Kavita (eds), No Touching, No Spitting, No Praying: The Museum in South Asia, 2015, Routledge, PDF on academia.edu

- Singh, Upinder, A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, 2008, Pearson Longman, ISBN 9788131716779, google books

- Tunio, Hafeez, "With King Priest 'in hiding', Dancing Girl yet to take the road back home", 16 July 2012, The Express Tribune

- Vidale, Massimo, Treasures from the Oxus: The Art and Civilization of Central Asia, 2017, I.B. Tauris, ISBN 9781838609764, google books

Further reading

[edit]- Ardeleanu-Jansen, A., "The Sculptural Art of the Harappa Culture", pp. 167–178 in Michael Jansen; Máire Mulloy; Günter Urban (eds.), Forgotten Cities on the Indus: Early Civilization in Pakistan from the 8th to the 2nd Millennium BC, 1991, Oxford University Press/Verlag Philipp von Zabern, ISBN 978-3-8053-1171-7.

- Vidale, Massimo, "A “Priest King” at Shahr-i Sokhta?", December 2017, Archaeological Research in Asia 15, DOI:10.1016/j.ara.2017.12.001