Pride of the Marines

| Pride of the Marines | |

|---|---|

Original film poster | |

| Directed by | Delmer Daves |

| Written by | Delmer Daves (uncredited) Marvin Borowsky |

| Screenplay by | Albert Maltz |

| Based on | Al Schmid, Marine 1944 book by Roger Butterfield |

| Produced by | Jerry Wald |

| Starring | John Garfield Eleanor Parker |

| Cinematography | J. Peverell Marley |

| Edited by | Owen Marks |

| Music by | Franz Waxman |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 119 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1,072,000[2] |

| Box office | $3,019,000[2] |

Pride of the Marines is a 1945 American biographical war film starring John Garfield and Eleanor Parker. It tells the story of U.S. Marine Al Schmid in World War II, his heroic stand against a Japanese attack during the Battle of Guadalcanal, in which he was blinded by a grenade, and his subsequent rehabilitation. The film was based on the 1944 Roger Butterfield book Al Schmid, Marine.

Albert Maltz was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Plot

[edit]Philadelphia steel worker Al Schmid has no intention of marriage until he meets Ruth Hartley. Al is impressed by Ruth and the couple fall in love. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Al joins the Marines. Before his departure, Al proposes marriage to Ruth on the train station platform.

Al is assigned to fight in the Pacific War. In August, 1942, on the island of Guadalcanal, Al is in the crew of a M1917 Browning machine gun at a gun emplacement with his buddies Lee Diamond and Johnny Rivers of "H" Company 2nd Battalion First Marines. During the Battle of the Tenaru, the onslaught by the Japanese is particularly heavy, but the men are able to kill some 200 of the enemy. Rivers is killed, Diamond is wounded, and Al is blinded by a hand grenade.

Sent stateside, Al navigates through a difficult rehabilitation. Diamond, also recovering, tries to console and encourage Al. However, Al, though hopeful of restoration of his sight, bitterly resents loss of his independence and attempts to break up with Ruth to spare her his pain.

Al is told he will be awarded the Navy Cross, and the ceremony will be in Philadelphia, his home town, where he will be permanently transferred to the Naval Hospital there. Diamond accompanies him. Al is angry and afraid of being forced to confront Ruth; and, believes she will pity him. He insists that he will get his sight back someday and until then will not be dependent upon family and friends. Ruth comes to Philadelphia's 30th Street Station and she and Diamond plan a ruse to make Al believe he is being taken to the hospital, when Ruth is actually taking him home. Going up the steps to the house, he realizes he is home. Ruth assures Al that his blindness makes no difference to her, and that she still loves him. During the award ceremony, he re-lives the events on Guadalcanal. As they leave the Navy Yard, he tells Ruth to get the cab with the red top on it – "it's fuzzy, but it's red." Al warns her that there is no guarantee he will see well again.[3] "Whichever way it is, we'll do it together," she replies. Al tells the cabbie to take them home.

Cast

[edit]- John Garfield as Al Schmid

- Eleanor Parker as Ruth Hartley

- Dane Clark as Lee Diamond

- John Ridgely as Jim Merchant

- Rosemary DeCamp as Virginia Pfeiffer

- Ann Doran as Ella May Merchant

- Ann E. Todd as Loretta Merchant

- Anthony Caruso as Johnny Rivers

Production

[edit]During the Battle of Guadalcanal, two enlisted Marines, Mitchell Paige and John Basilone were awarded the Medal of Honor for their use of the M1917 Browning machine gun against massed Japanese charges. In Jim Proser's book I'm Staying With My Boys: The Heroic Life of Sgt. John Basilone USMC[4] Proser tells of Basilone's friendship with John Garfield and Eddie Bracken when they toured the United States selling war bonds.

Screenwriters A. I. Bezzerides and Alvah Bessie developed a 26-page treatment of Roger Butterfield's book Al Schmid Marine.[5] Martin Borowsky also did an adaptation of Butterfield's book that was rewritten by Albert Maltz, to whom Garfield had spoken about Butterfield's story. Prior to filming, Garfield visited American soldiers in hospitals in Italy.[6]

In the liner notes for its re-mastered 2010 DVD release of the film, Warner Brothers said, "Garfield championed turning Al's story into a film ever since he read about the Marine's ordeal in Life magazine".[7] Garfield met Schmid during his rehabilitation, before a movie was ever planned.[8] Once the film was planned, Garfield lived with the Schmids for several weeks, becoming friends with the couple.[9]

Bessie and Maltz were later blacklisted over their "un-American" political opinions, as two of the Hollywood Ten.

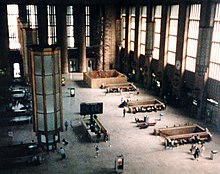

Film locations in Philadelphia include the 6500 block of Tulip Street.[10] Schmid's departure and subsequent homecoming from war were filmed at photogenic 30th Street Station,[11] although in reality he was met upon his return by his wife and parents at the more prosaic North Philadelphia Station, with news media on hand reporting the reunion.[12]

Reception

[edit]Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called the film "a splendid documentation of a dramatic crisis in a hero's life," with performances that were "all unqualifiedly excellent ... To say that this picture is entertaining to a truly surprising degree is an inadequate recommendation. It is inspiring and eloquent of a quality of human courage that millions must try to generate today."[13] Variety called it "a two-hour celluloid saga which should inspire much pride for many. As an entertainment film with a forceful theme, so punchy that its 'message' aspects are negligible, it is a credit to all concerned ... [Garfield] gives a vividly histrionic performance that will not be easily forgotten."[14] Harrison's Reports called the film "sensitive and at times forceful" and called Garfield "very good," but found the discourses by hospitalized servicemen "so long drawn out that they interrupt the flow of the story."[15] Wolcott Gibbs of The New Yorker wrote: "In spite of the fact that most of this has a somewhat familiar and mechanical air, the picture has its effective moments, mostly owing to Mr. Garfield's honest and very intelligent performance."[16]

Box office

[edit]According to Warner Bros records the film earned $2,295,000 domestically and $724,000 foreign.[2]

Adaptations

[edit]Pride of the Marines was adapted as a one-hour radio play on the December 31, 1945 episode of Lux Radio Theater,[17] with original stars John Garfield, Eleanor Parker, and Dane Clark reprising their roles from the film, and as a half-hour radio drama on the June 15, 1946 episode of Academy Award Theater,[18] starring Garfield but with different co-stars.

As a bonus feature in the Lux Radio Theater version, Al Schmid is introduced by phone and speaks with Garfield.

References

[edit]- ^ McGrath 1993, p. 73.

- ^ a b c "Appendix 1". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 15: 1–31. 1995. doi:10.1080/01439689508604551.

- ^ Al Schmid recovered partial sight in one eye.

- ^ Proser, Jim; Cutter, Jerry (2010). I'm Staying with My Boys: The Heroic Life of Sgt. John Basilone, USMC. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-61144-6. Retrieved March 22, 2014.

- ^ Norden, Martin F. (1994). Cinema Of Isolation: A History of Physical Disability in the Movies. Rutgers University Press. p. 342. ISBN 978-0813521046.

- ^ McGrath 1993, p. 71.

- ^ Pride of the Marines (DVD). Warner Brothers. 1945.

- ^ Gerber, David A., In Search of Al Schmid quoted in Mitchell & Snyder (1997, p. 115)

- ^ McGrath 1993, p. 72.

- ^ "Historical Northeast Philadelphia: Stories and Memories ~1994". Archived from the original on May 13, 2010.

- ^ Pride of the Marines (DVD). Warner Brothers. 1945. Event occurs at 0:30:00 and 1:41:00.

- ^ "Blind Hero Back Home". Philadelphia Inquirer. January 19, 1943. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (August 25, 1945). "Movie Review – Pride of the Marines". The New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ "Film Reviews". Variety. New York: Variety, Inc.: 22 August 8, 1945.

- ^ "'Pride of the Marines' with John Garfield and Eleanor Parker". Harrison's Reports: 126. August 11, 1945.

- ^ Gibbs, Wolcott (September 8, 1945). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. New York: F-R Publishing Corp. p. 43.

- ^ "Networks Plan Special New Year's Eve Shows". Youngstown Vindicator (Ohio). December 31, 1945. p. 7. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ "SATURDAY SELECTIONS". Youngstown Vindicator (Ohio). June 15, 1946. p. 4 (Peach section). Retrieved September 21, 2020.

Works cited

[edit]- Mitchell, David T.; Snyder, Sharon L. (1997). The Body and Physical Difference: Discourses of Disability. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472066599.

- McGrath, Patrick J. (1993). John Garfield: The Illustrated Career in Films and on Stage. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0899508672.

External links

[edit]- 1945 films

- 1940s biographical drama films

- 1945 drama films

- American biographical drama films

- American black-and-white films

- Culture of Philadelphia

- 1940s English-language films

- Films about the United States Marine Corps

- Films directed by Delmer Daves

- Films scored by Franz Waxman

- Films shot in Philadelphia

- Pacific War films

- Warner Bros. films

- World War II films made in wartime

- Films about disability in the United States

- Films about blind people in the United States

- English-language biographical drama films