Prescription drug addiction

| Prescription drug addiction | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adderall is a commonly abused stimulant drug containing amphetamine.[1] | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology |

| Complications | Drug overdose |

| Frequency | Estimated over 3.43 million prescription opioid users and 3.42 million prescription stimulant users worldwide.[2] |

Prescription drug addiction is the chronic, repeated use of a prescription drug in ways other than prescribed for, including using someone else’s prescription.[3][4] A prescription drug is a pharmaceutical drug that may not be dispensed without a legal medical prescription. Drugs in this category are supervised due to their potential for misuse and substance use disorder. The classes of medications most commonly abused are opioids, central nervous system (CNS) depressants and central nervous stimulants.[3]: 5 In particular, prescription opioid is most commonly abused in the form of prescription analgesics.[5][6]

Prescription drug addiction was recognized as a significant public health and law enforcement problem worldwide in the past decade due to its medical and social consequences.[7] Particularly, the United States declared a public health emergency regarding increased drug overdoses in 2017.[8] Since then, multiple public health organizations have emphasized the importance of prevention, early diagnosis and treatments of prescription drug addiction to address this public health issue.[9]

Causes and risk factors

[edit]There are multiple risk factors that can increase the chance of developing drug addiction, including patient factors, nature of drug and over-prescription.

Patient factors

[edit]Studies have indicated that adolescents and young adults were particularly vulnerable to prescription drug abuse.[10] People with acute or chronic pain, anxiety disorders and ADHD were at increased risk for addiction comorbidity.[11] History of illicit drug use and substance use disorder were consistently identified as risk factors for prescription drug abuse.[12]

Misuse of opioid analgesics is frequently associated with mental health disorder, including depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and anxiety disorders.[13][14] Some risk factors for opioid and benzodiazepine sedatives or tranquilizers addiction are white race, female sex, panic symptoms, other psychiatric symptoms, alcohol and cigarette dependence and history of illicit drug use.[15][16][17] Addiction to pharmaceutical stimulants have been predominantly among adolescents and young adults.[18][19]

Drug characteristics

[edit]Patients who have been prescribed medications to treat a health condition or disorder are shown to be more vulnerable to prescription drug abuse and addiction, especially when the prescribed medicine falls into the same drug classes of common illicit drugs.[20] For example, methylphenidate and amphetamines are in the same stimulant category as cocaine and methamphetamine, while hydrocodone and oxycodone are under the opioid category as heroin.[10]

Key pharmacological factors associated with drug addiction include:

- high frequency of drug use

- high doses administered

- rapid rate of onset of action

- high drug potency

- co-ingestion of psychoactive substances with similar (eg. sedatives and alcohol) or different pharmacological profiles (eg. stimulants and nicotine) can result in additional reinforcement of addiction.[10][11][21]

Over-prescription and doctor shopping

[edit]Health practitioners can prescribe drugs in a number of ways that inadvertently and unintentionally contribute to prescription drug abuse..[3]: 29 They may inappropriately prescribe drugs due to influence by ill-informed, careless or deceptive patients or by succumbing to patient pressure..[3]: 29

The American Medical Association describes four mechanism by which a physician becomes involved in overprescribing in its four-”Ds” model:

- ’’’Dated’’’: the physician is outdated regarding knowledge of pharmacology and the differential diagnosis and management of diseases.

- ’’’Duped’’’: the physician may be vulnerable to a manipulative patient.

- ’’’Dishonest’’’: a dishonest physician may be motivated to write prescriptions for controlled substances under financial incentives.

- ’’’Disabled’’’: a physician with medical or psychiatric disability such that they have “loose” standards in prescribing controlled substances.[11][22]

The above over-prescription practices can lead to the aggravation of prescription drug addiction.[11]

A person may also gain access to prescription drugs via doctor shopping..[3]: 29 "Doctor shopping" describes a practice in which a person searches for multiple sources of drugs by visiting different health practitioners and presenting a different list of complaints to each practitioner; the patient will then obtain multiple prescriptions and fill them at different pharmacies.[23]

Commonly abused drug categories

[edit]Opioid analgesics

[edit]

Opioid painkillers exert CNS depressant effects by binding to opioid receptors.[24] Its psychoactive properties potentially cause euphoria.[25] Changes in the pain management including more liberal opioids prescription for chronic pain conditions, prescription of higher doses and the development of more potent opioid drugs play an important role contributing to the current epidemic of prescription opioid addiction.[26] Examples of opioid drugs include morphine, codeine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, fentanyl, tramadol and methadone.[27]

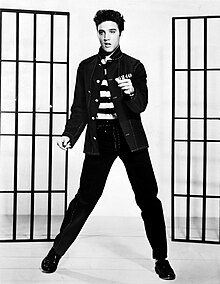

Stimulants

[edit]Stimulants are drugs that increase alertness and attention.[28] This class of drugs have been frequently prescribed for patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in many countries.[29][30] In addition to taking higher doses of medication than prescribed, stimulant users may also combine prescribed stimulants with illicit drugs or alcohol in order to induce euphoria.[31] Examples of prescribed stimulants include amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, methamphetamine and methylphenidate.[32]

Anxiolytic sedative-hypnotics

[edit]

Sedatives have potent, dose-dependent CNS depressant effects.[24] These drugs exert a calming effect and may also induce sleepiness.[34] Sedative-hypnotic medications are commonly prescribed for anti-anxiety or sleeping aid purposes.[35]

A major class of sedative-hypnotics causing addiction is benzodiazepines, which includes alprazolam, diazepam, clonazepam and lorazepam.[36]

Consequences

[edit]Prescription drug addiction is usually associated with both medical and social consequences.

Medical consequences

[edit]Different drug classes have different side effects. Long-term medical conditions induced by opioid include infection, hyperalgesia, opioid-induced bowel syndrome, opioid-related leukoencephalopathy and opioid amnestic syndrome.[32] Misuse of prescribed opioids medications is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.[37]

Syndromes of overdose of stimulants may include tremor, confusion, hallucinations, anxiety and seizures.[38]

Inappropriate use of prescribed benzodiazepines may induce nystagmus, stupor or coma, altered mental status (most commonly depression) and respiratory depression.[39]

Social consequences

[edit]Addiction to prescription drugs also brings social impacts. Due to the CNS effect caused by misuse of medications, people are more likely to have poor judgement and thus engaging in risky behaviors. Polydrug addiction with illegal or recreational drugs is also common.[40] It was found that adolescents with opioid addiction show higher rates of past-year criminal behaviors.[41] The risk of motor vehicle accidents may increase if consciousness is greatly reduced.[42] Addiction may also deteriorate academic or work performance and worsen relationships.[32]

Diagnosis

[edit]Signs and symptoms

[edit]

The signs and symptoms of opioids addiction include decreased body temperature and blood pressure, constipation, decreased sex drive, euphoria and others.[32] Conversely, people with addiction to stimulants often have increased blood pressure, heart rate, body temperature, decreased sleep and appetite.[43] Stimulants may cause anxiety and paranoia as well.[44] Addiction of benzodiazepines is diagnosed based on the withdrawal syndrome occurred after termination of regular use.[45] Benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms are similar to anxiety, including insomnia, excitability, restlessness, panic attacks and so on.[46]

Screening and testing

[edit]Screening tools with high validity are available to assess patients’ risk for opioid misuse, which include rapid opioid dependence screen (RODS), Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS) and OWLS.[47][48]

There is a standardized list of diagnostic criteria provided by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders for patients with positive screening results.[49] Additionally, urine drug testing can be an accurate method to measure specific biomarkers after metabolism.[50]

Treatment

[edit]Pharmacotherapies

[edit]

When a chronic prescription drug user suddenly ceases the use of an addictive drug, the person may experience unpleasant withdrawal symptoms depending on the drug type.[24] A constant opioid user may experience withdrawal symptoms such as nausea and diarrhea.[47] Detoxification is a procedure which treats addicts in withdrawal with low doses of a synthetic opiate drug which helps reduce the severity of their withdrawal symptoms.[32]: 162 This type of pharmacotherapy with an opioid agonist or antagonist is adopted widely, together with adjunct psychotherapy to prevent relapse. Examples of medications include methadone, naltrexone and clonidine.[51]

Currently, no FDA-approved medications are available for stimulants addiction.[52] However, some agents including bupropion, naltrexone and mirtazapine have demonstrated positive effects in treating addiction to amphetamine-type stimulants.[44] Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors have shown to be a potential treatment target.[53]

Notably, benzodiazepines addiction often occurs as a result of polydrug abuse, most commonly with opioids.[24] Medically supervised detoxification remains the first-line treatment for benzodiazepines addiction.[54] The use of other medication to aid withdrawal has not been well-developed.[55]

Behavioral therapies

[edit]Cognitive behavioral therapy and the Matrix model are treatment options for stimulant addicts that have been shown to be effective in preventing relapse, despite that patients addicted to opioid may not respond well to behavioral therapy.[56]

Prevention

[edit]Patients, healthcare providers, the government, pharmaceutical companies and a variety of stakeholders can contribute to the prevention of prescription drug misuse and its subsequent addiction.

Regulations regarding drug prescription

[edit]In addition to existing controlled substance scheduling systems, mandatory prescriber registration, education and training, many governments launched various initiatives and regulations to minimize misuse of prescription drugs.

For example, many healthcare providers are legally required to participate in local prescription-drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) to record patient drug use.[57] Nationwide PDMPS are effective in reducing abuse and diversion of prescription medications, and promote safer prescribing practices for patients.[57] PDMPs are effective against doctor shopping and incidents of over-prescription.[57][58]

Furthermore, different regions established specialized agencies to oversee drug addiction and its related regulations. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) and the French public interest group OFDT were established in 1993 to provide information concerning drug addiction and consequences.[59][60] Similarly, the US government founded the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) directed toward reducing drug misuse and overdose in 1974.[61] In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published its CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain.[62]

Screening for addiction

[edit]Addiction disorders affect 20 to 50 percent of hospitalized patients; therefore physicians must integrate basic screening questions into all histories and physical examinations.[11] Some major evidence-based assessment tools include the Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment, the National Institute on Drug Use Screening Tool, the CRAFFT 2.0 questionnaire, and the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10).[63]

There are many programs to assist addictive individuals in achieving abstinence. In countries like Brazil, the US and India, addictive patients may be referred to 12-step programs such as Alcoholic Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, and Pills Anonymous.[35][64]

Optimize alternative treatments

[edit]Safer, non-controlled and non-addictive medications serve as an alternative to controlled substances.[11] For example, abuse-deterrent formulations (ADF) are drug formulations that lower a drug’s addictiveness and/or prevent misuse by snorting or injection. ADFs have shown to decrease the illicit value of drugs and effectively eradicate substance addiction.[63][65]

Non-pharmacologic treatments with self-management strategies are highly recommended, such as behavioral treatments, relaxation techniques, physical therapy and psychotherapy.[11]

Ensuring drug compliance

[edit]Pharmacists improve drug compliance by counselling patients on medication instructions, along with educating patients about potential side effects related to medications.[66] Nevertheless, healthcare practitioners are responsible for recognizing problematic patterns in prescription drug use.[20] They may also use prescription-drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) to track drug prescription and dispensing patterns in patients.[20]

Patient-wise, some organizations have suggested ways to use prescription drugs properly. For example, the NIDA guideline recommends patients to:

- following the directions as explained on the label or by the pharmacist

- being aware of potential interactions with other drugs as well as alcohol

- never stopping or changing a dosing regimen without first discussing it with the doctor

- never using another person’s prescription and never giving their prescription medications to others

- storing prescription stimulants, sedatives, and opioids safely.[20]

Additionally, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provides a guideline for proper disposal of unused or expired medications.[20][67]

Epidemiology

[edit]Non-medical use of prescription opioids has been documented in many countries, most notably in West and North Africa, the Near and Middle East, and North America.[68]

United States

[edit]In 2005, the US National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) demonstrated that 6.4 million people aged 12 or older had used prescription drugs for non-medical reasons during the past month, including pain relievers, tranquillizers and stimulants.[35]

From 2006 to 2016, the total weight of stimulants prescribed in the US nearly doubled;[29] however, the trend of prescription stimulant misuse has been gradually declining since 2017.[68][69]

In 2017, it was estimated that approximately 76 million adults in the US were prescribed with opioid drugs in the previous year, with 12 percent of them reporting prescription opioid misuse between 2016 and 2017.[70] An estimate of more than 1 million Americans misused prescription stimulants, 2 million misused prescription analgesics, 1.5 million misused tranquillizers, and 271,000 misused sedatives for the first time within the past year.[71]

United Kingdom

[edit]In the United Kingdom, deaths from Tramadol (a synthetic opioid painkiller) overdose have risen to 240 per annum as of 2014.[72]

Europe

[edit]In Europe, methadone is the most widely prescribed opioid substitution medication, accounting for about 63 percent of substitution clients, followed by 35 percent of clients treated with buprenorphine-based medications. An average of 6 percent of students from the EU and Norway reported lifetime use of sedatives or tranquillizers without a doctor’s prescription.[73] In 2019, there was an increasing trend of prescription opioid addiction among Europe.[74] Both amphetamines and methamphetamines are stimulant drugs commonly used in Europe, though amphetamines were more frequently prescribed. Methamphetamine use has traditionally been limited to the Czech Republic and Slovakia, although there were signs of increase in other European countries.[73]

Asia

[edit]In comparison to the West, Asia-Pacific has a scarcity of data on prescription drug abuse. Still, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime stated that prescription drug abuse is a growing epidemic among recreational drug users in South Asia.[75] Although relevant studies in China were limited, they revealed a similar prevalence of prescription drug misuse among adolescents and young adults, which was 5.9 percent and 25.9 percent, respectively.[76] Most Asian studies, including those from Japan, Thailand, and Singapore, revealed the existence of prescription drug misuse in Asia, but their prevalence rates were found to be lower than that reported in Western developed countries.[76] In 2019, there was an increasing trend of prescription opioid addiction in India.[77]

South Africa

[edit]In comparison to the US, the prevalence of illicit drug use (including prescription drugs) in South Africa is relatively low.[78] Prescription drug and over-the-counter (OTC) drug abuse together constitutes 2.6 percent of all primary illicit substances admitted to South African drug treatment facilities.[78] However, lifetime illicit drug use for prescription or OTC medicines was highest among adolescents, at 16 percent prevalence rate, followed by inhalants, club drugs and others.[78]

See also

[edit]

External links

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Schachter R (February 2012). "A New Prescription for Fighting Drug Abuse". District Administration. 48 (2): 41. ISSN 1537-5749. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "Booklet 2: Global overview of drug demand and supply" (PDF). World Drug Report 2018. Vienna, Austria: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2018. ISBN 978-92-1-148304-8.

- ^ a b c d e The non-medical use of prescription drugs - Policy Direction Issues (Discussion Paper) (PDF) (Report). United Nations Office On Drugs And Crime. September 2011. p. 1. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "The Science of Drug Use and Addiction: The Basics". National Institute on Drug Abuse. 25 June 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "Curbing prescription opioid dependency". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 95 (5): 318–319. May 2017. doi:10.2471/BLT.17.020517. PMC 5418819. PMID 28479631.

- ^ Holmes D (January 2012). "Prescription drug addiction: the treatment challenge". Lancet. 379 (9810): 17–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60007-5. PMID 22232799. S2CID 12678152.

- ^ Executive summary. World Drug Report 2018 (Report). United Nations. June 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "What is the U.S. Opioid Epidemic?". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 4 December 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ 2019 National Drug Threat Assessment (NDTA) (PDF) (Report). US Drug Enforcement Administration. December 2019.

- ^ a b c Compton WM, Volkow ND (June 2006). "Abuse of prescription drugs and the risk of addiction". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 83 (Suppl 1): S4-7. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.020. PMID 16563663.

- ^ a b c d e f g Longo LP, Parran T, Johnson B, Kinsey W (April 2000). "Addiction: part II. Identification and management of the drug-seeking patient". American Family Physician. 61 (8): 2401–8. PMID 10794581.

- ^ Riva JJ, Noor ST, Wang L, Ashoorion V, Foroutan F, Sadeghirad B, et al. (November 2020). "Predictors of Prolonged Opioid Use After Initial Prescription for Acute Musculoskeletal Injuries in Adults : A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies". Annals of Internal Medicine. 173 (9): 721–729. doi:10.7326/M19-3600. PMID 32805130. S2CID 221164563.

- ^ Fleming MF, Balousek SL, Klessig CL, Mundt MP, Brown DD (July 2007). "Substance use disorders in a primary care sample receiving daily opioid therapy". The Journal of Pain. 8 (7): 573–82. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2007.02.432. PMC 1959336. PMID 17499555.

- ^ Boscarino JA, Rukstalis M, Hoffman SN, Han JJ, Erlich PM, Gerhard GS, Stewart WF (October 2010). "Risk factors for drug dependence among out-patients on opioid therapy in a large US health-care system". Addiction. 105 (10): 1776–82. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03052.x. PMID 20712819.

- ^ McHugh RK, Nielsen S, Weiss RD (January 2015). "Prescription drug abuse: from epidemiology to public policy". Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 48 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2014.08.004. PMC 4250400. PMID 25239857.

- ^ Becker WC, Fiellin DA, Desai RA (October 2007). "Non-medical use, abuse and dependence on sedatives and tranquilizers among U.S. adults: psychiatric and socio-demographic correlates". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 90 (2–3): 280–7. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.009. PMC 3745028. PMID 17544227.

- ^ Back SE, Payne RL, Simpson AN, Brady KT (November 2010). "Gender and prescription opioids: findings from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health". Addictive Behaviors. 35 (11): 1001–7. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.06.018. PMC 2919630. PMID 20598809.

- ^ Kaye S, Darke S (March 2012). "The diversion and misuse of pharmaceutical stimulants: what do we know and why should we care?". Addiction. 107 (3): 467–77. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03720.x. PMID 22313101.

- ^ Looby A, De Young KP, Earleywine M (September 2013). "Challenging expectancies to prevent nonmedical prescription stimulant use: a randomized, controlled trial". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 132 (1–2): 362–8. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.003. PMC 3708969. PMID 23570818.

- ^ a b c d e How can prescription drug misuse be prevented?. National Institute on Drug Abuse (Report). June 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Volkow ND, Swanson JM (November 2003). "Variables that affect the clinical use and abuse of methylphenidate in the treatment of ADHD". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (11): 1909–18. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1909. PMID 14594733.

- ^ Wilford BB (1990). Balancing the response to prescription drug abuse: report of a national symposium on medicine and public policy. Chicago: American Medical Association: Department of Substance Abuse. pp. 19–24.

- ^ Preuss CV, Kalava A, King KC (2021). "Prescription of Controlled Substances: Benefits and Risks". StatPearls. PMID 30726003.

- ^ a b c d Weiss RD (2012). "Drug Abuse and Dependence". Goldman's Cecil Medicine. pp. 153–159. doi:10.1016/B978-1-4377-1604-7.00033-6. ISBN 978-1-4377-1604-7.

- ^ Brody H (September 2019). "Opioids". Nature. 573 (7773): S1. Bibcode:2019Natur.573S...1B. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-02681-7. PMID 31511676.

- ^ "Pain Management & Opioid Use". American Academy of Family Physicians. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Volkow ND, Jones EB, Einstein EB, Wargo EM (February 2019). "Prevention and Treatment of Opioid Misuse and Addiction: A Review". JAMA Psychiatry. 76 (2): 208–216. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3126. PMID 30516809. S2CID 54626908.

- ^ "Prescription Drugs". Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ a b Piper BJ, Ogden CL, Simoyan OM, Chung DY, Caggiano JF, Nichols SD, McCall KL (2018). "Trends in use of prescription stimulants in the United States and Territories, 2006 to 2016". PLOS ONE. 13 (11): e0206100. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1306100P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0206100. PMC 6261411. PMID 30485268.

- ^ Grimmsmann T, Himmel W (January 2021). "The 10-year trend in drug prescriptions for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in Germany". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 77 (1): 107–115. doi:10.1007/s00228-020-02948-3. PMC 7782395. PMID 32803292.

- ^ Wilens TE, Gignac M, Swezey A, Monuteaux MC, Biederman J (April 2006). "Characteristics of adolescents and young adults with ADHD who divert or misuse their prescribed medications". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 45 (4): 408–14. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000199027.68828.b3. PMID 16601645.

- ^ a b c d e f g Maisto SA, Galizio M, Connors GJ (January 2018). Drug Use and Abuse. Cengage Learning. p. 261. ISBN 978-1-337-40897-4.

- ^ "Prince death: Singer's family sues doctor over opioid addiction". BBC News. 25 August 2018.

- ^ Hoffman RS, Howland MA, Lewin NA, Nelson LS, Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum N (2015). Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies (10th ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-07-180184-3. OCLC 861895453.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Lessenger JE, Feinberg SD (2008). "Abuse of prescription and over-the-counter medications". Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 21 (1): 45–54. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2008.01.070071. PMID 18178702. S2CID 25185500.

- ^ Longo LP, Johnson B (April 2000). "Addiction: Part I. Benzodiazepines--side effects, abuse risk and alternatives". American Family Physician. 61 (7): 2121–8. PMID 10779253.

- ^ Imam MZ, Kuo A, Ghassabian S, Smith MT (March 2018). "Progress in understanding mechanisms of opioid-induced gastrointestinal adverse effects and respiratory depression". Neuropharmacology. 131: 238–255. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.12.032. PMID 29273520. S2CID 3414348.

- ^ Spiller HA, Hays HL, Aleguas A (July 2013). "Overdose of drugs for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: clinical presentation, mechanisms of toxicity, and management". CNS Drugs. 27 (7): 531–43. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0084-8. PMID 23757186. S2CID 40931380.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association (2013-05-22). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth ed.). American Psychiatric Association. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. hdl:2027.42/138395. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ^ Subramaniam GA, Stitzer MA (April 2009). "Clinical characteristics of treatment-seeking prescription opioid vs. heroin-using adolescents with opioid use disorder". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 101 (1–2): 13–9. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.015. PMC 2746065. PMID 19081205.

- ^ Subramaniam GA, Stitzer MA (April 2009). "Clinical characteristics of treatment-seeking prescription opioid vs. heroin-using adolescents with opioid use disorder". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 101 (1–2): 13–9. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.015. PMC 2746065. PMID 19081205.

- ^ De Maricourt P, Gorwood P, Hergueta T, Galinowski A, Salamon R, Diallo A, et al. (2016). "Balneotherapy Together with a Psychoeducation Program for Benzodiazepine Withdrawal: A Feasibility Study". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2016: 8961709. doi:10.1155/2016/8961709. PMC 5124454. PMID 27956923. S2CID 8266146.

- ^ Hamilton GJ (2009). "Prescription drug abuse". Psychology in the Schools. 46 (9): 892–898. doi:10.1002/pits.20429.

- ^ a b Cao DN, Shi JJ, Hao W, Wu N, Li J (June 2016). "Advances and challenges in pharmacotherapeutics for amphetamine-type stimulants addiction". European Journal of Pharmacology. 780: 129–35. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.03.040. PMID 27018393.

- ^ Committee on Safety of Medicines (January 1988). "Benzodiazepines, dependence and withdrawal symptoms". UK Government Bulletin to Prescribing Doctors. 21 (1–2).

- ^ Cloos JM, Ferreira V (January 2009). "Current use of benzodiazepines in anxiety disorders". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 22 (1): 90–5. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32831a473d. PMID 19122540. S2CID 20715355.

- ^ a b Wickersham JA, Azar MM, Cannon CM, Altice FL, Springer SA (January 2015). "Validation of a Brief Measure of Opioid Dependence: The Rapid Opioid Dependence Screen (RODS)". Journal of Correctional Health Care. 21 (1): 12–26. doi:10.1177/1078345814557513. PMC 4435561. PMID 25559628.

- ^ Picco L, Middleton M, Bruno R, Kowalski M, Nielsen S (November 2020). "Validation of the OWLS, a Screening Tool for Measuring Prescription Opioid Use Disorder in Primary Care". Pain Medicine. 21 (11): 2757–2764. doi:10.1093/pm/pnaa275. PMID 32869062.

- ^ Ehlers CL, Gizer IR, Gilder DA, Wilhelmsen KC (December 2011). "Linkage analyses of stimulant dependence, craving, and heavy use in American Indians". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 156B (7): 772–80. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.31218. PMC 3188982. PMID 21812097.

- ^ Raouf M, Bettinger JJ, Fudin J (April 2018). "A Practical Guide to Urine Drug Monitoring". Federal Practitioner. 35 (4): 38–44. PMC 6368048. PMID 30766353.

- ^ Strain EC, Stitzer ML (2006). The Treatment of Opioid Dependence. JHU Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8018-8219-7.

- ^ "How can prescription drug addiction be treated?". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ Sofuoglu M, Mooney M (November 2009). "Cholinergic functioning in stimulant addiction: implications for medications development". CNS Drugs. 23 (11): 939–52. doi:10.2165/11310920-000000000-00000. PMC 2778856. PMID 19845415.

- ^ Diaper AM, Law FD, Melichar JK (February 2014). "Pharmacological strategies for detoxification". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 77 (2): 302–14. doi:10.1111/bcp.12245. PMC 4014033. PMID 24118014.

- ^ Guaiana G, Barbui C (June 2016). "Discontinuing benzodiazepines: best practices". Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 25 (3): 214–6. doi:10.1017/S2045796016000032. PMC 6998737. PMID 26818890.

- ^ Blanchard J, Hunter SB, Osilla KC, Stewart W, Walters J, Pacula RL (May 2016). "A Systematic Review of the Prevention and Treatment of Prescription Drug Misuse". Military Medicine. 181 (5): 410–23. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00009. PMID 27136647.

- ^ a b c Worley J (May 2012). "Prescription drug monitoring programs, a response to doctor shopping: purpose, effectiveness, and directions for future research". Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 33 (5): 319–28. doi:10.3109/01612840.2011.654046. PMID 22545639. S2CID 33391190.

- ^ Haffajee RL, Jena AB, Weiner SG (March 2015). "Mandatory use of prescription drug monitoring programs". JAMA. 313 (9): 891–2. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.18514. PMC 4465450. PMID 25622279.

- ^ "L'OFDT". Observatoire Français Des Drogues et Des Toxicomanies (in French). 26 June 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "About EMCDDA". European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ National Institute on Drug Abuse. "About NIDA". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ "About CDC's Opioid Prescribing Guideline". www.cdc.gov. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 17 February 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ a b "5 Evidence-Based Screening Tools for Addiction Professionals". Advanced Recovery Systems. 7 December 2017.

- ^ Salwan J, Katz CL (26 June 2014). "A review of substance [corrected] use disorder treatment in developing world communities". Annals of Global Health. 80 (2): 115–21. doi:10.1016/j.aogh.2014.04.010. PMID 24976549.

- ^ Maldonado R, Baños JE, Cabañero D (February 2016). "The endocannabinoid system and neuropathic pain". Pain. 157 (Suppl 1): S23–S32. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000428. hdl:10230/34808. PMID 26785153. S2CID 6415727.

- ^ Albrecht S (18 May 2011). "The Pharmacist's Role in Medication Adherence". US Pharmacist. 36 (5): 45–48.

- ^ "Disposal of Unused Medicines: What You Should Know". FDA. 23 September 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ a b World Drug Report 2020 (Set of 6 Booklets). United Nations. 2021. ISBN 978-92-1-148345-1.

- ^ "2019 NSDUH Annual National Report". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). U.S. Department Health & Human Services. 11 September 2020.

Graphics from the Key Findings Report

- ^ Griesler PC, Hu MC, Wall MM, Kandel DB (September 2019). "Medical Use and Misuse of Prescription Opioids in the US Adult Population: 2016-2017". American Journal of Public Health. 109 (9): 1258–1265. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305162. PMC 6687264. PMID 31318593.

- ^ What is the scope of prescription drug misuse? (Report). National Institute on Drug Abuse. 13 April 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "Current UK data on opioid misuse". Faculty of Pain Medicine of the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ a b European Monitoring Centre for Drugs Drug Addiction (2018). European drug report 2018: Trends and developments. Publications Office. doi:10.2810/800331. ISBN 978-92-9497-272-9.

- ^ European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (6 June 2019). European drug report 2019: trends and developments. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. ISBN 978-92-9497-398-6.

- ^ Misuse of prescription drugs: A South Asia perspective (PDF) (Report). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2011.

- ^ a b Chan WL, Wood DM, Dargan PI (April 2021). "Prescription medicine misuse in the Asia-Pacific region: An evolving issue?". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 87 (4): 1660–1667. doi:10.1111/bcp.14638. PMID 33140471. S2CID 226242899.

- ^ Ambekar A, Agrawal A, Rao R, Mishra AK, Khandelwal SK, Chadda RK (February 2019). Magnitude of Substance Use in India 2019 (PDF) (Report). New Delhi: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India.

- ^ a b c Peltzer K, Ramlagan S, Johnson BD, Phaswana-Mafuya N (November 2010). "Illicit drug use and treatment in South Africa: a review". Substance Use & Misuse. 45 (13): 2221–43. doi:10.3109/10826084.2010.481594. PMC 3010753. PMID 21039113.