Porcupine river stingray

| Porcupine river stingray | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Myliobatiformes |

| Family: | Potamotrygonidae |

| Genus: | Potamotrygon |

| Species: | P. histrix

|

| Binomial name | |

| Potamotrygon histrix (J. P. Müller & Henle, 1834)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The porcupine river stingray (Potamotrygon histrix, sometimes incorrectly modified to Potamotrygon hystrix[2]) is a species of river stingray in the family Potamotrygonidae, the type of the Potamotrygon genus. It is found in the basins of the Paraná and Paraguay River basins in South America.[3] Most chemical weathering of minerals seems to take place in the upland drainage basins rather than on the floodplains, and most major solutes display conservative mixing in the river-floodplain system.[4] The population in the Rio Negro basin was described as a separated species, P. wallacei, in 2016.[5]

Appearance

[edit]

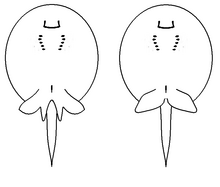

Almost circular in shape, it grows up to 40 cm (16 in) in disc width and 15 kg (33 lb) in weight.[3] The upper surface is covered with denticles (sharp tooth-like scales). The coloration is light brownish with mottled patterns on the dorso, and pink on the ventral side. As with all stingrays, the mouth and gill openings are on the underside, and the eyes and gills exits are on the dorsal side.

Sting

[edit]Like other stingrays, the fish of this genus have venomous barbs at the base of their tails, and are dangerous to humans.[3][6] The sting is replaced at roughly six-month intervals. It is an almost flat, barbed structure that can reach 6 cm (2.4 in) in length, and is covered with a toxic mucus, making any attack a very painful one.[3]

The natives of South America are said to fear the stingray more than the piranha.[7] However, they are not aggressive fish and not dangerous unless stepped on or otherwise threatened.

Aquarium

[edit]

Freshwater stingrays of the genus Potamotrygon are sometimes kept as exotic aquarium fish; though freshwater stingray of other genera do appear in the trade, most are from this genus. They are best kept with a deep, sandy substrate, in which they bury themselves, often with only their eyes visible. They are not territorial with other animals and can be kept in groups, provided a large enough aquarium is provided. They are carnivorous bottom-feeders and require strong filtration as they are rather sensitive to water conditions (any spike in NO2 levels can kill them with no warning).[6] Juvenile stingrays are unable to survive in waters that contain salinity over 20.6%.[8] Like many species of stingrays, P. histrix has been bred in captivity, but they require a large tank. The male should be smaller than the female, as it is rather aggressive, biting the female during the mating process.[9] Males can be determined by the presence of claspers as in other chondrichthyans.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ Soto, J.M.R.; Charvet-Almeida, P.; Pinto de Almeida, M. (2009). "Potamotrygon histrix". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2009: e.T161657A5474126. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2009-2.RLTS.T161657A5474126.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Rosa, R.S.; Charvet-Almeida, P.; Quijada, C.C.D. (2010). "Biology of the South American Potamotrygonid Stingrays". In Carrier, J.C.; Musick, J.A.; Heithaus, M.R. (eds.). Sharks and Their Relatives II: Biodiversity, Adaptive Physiology, and Conservation. Marine Biology. Vol. 20100521. CRC Press. pp. 241–285. doi:10.1201/9781420080483-c5 (inactive 2024-11-11). ISBN 978-1-4200-8047-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|DUPLICATE_title=ignored (help)CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ a b c d Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Potamotrygon hystrix". FishBase. October 2017 version.

- ^ Hamilton, Stephen K.; Sippel, Suzanne J.; Calheiros, DÓbora F.; Melack, John M. (1997). "An anoxic event and other biogeochemical effects of the Pantanal wetland on the Paraguay River". Limnology and Oceanography. 42 (2): 257–272. Bibcode:1997LimOc..42..257H. doi:10.4319/lo.1997.42.2.0257.

- ^ Carvalho, M.R.d.; Rosa, R.S.; Araújo, M.L.G. (2016). "A new species of Neotropical freshwater stingray (Chondrichthyes: Potamotrygonidae) from the Rio Negro, Amazonas, Brazil: the smallest species of Potamotrygon". Zootaxa. 4107 (4): 566–586. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4107.4.5. PMID 27394840.

- ^ a b Dawes, John (2001). Complete Encyclopedia of the Freshwater Aquarium. New York: Firefly Books Ltd. ISBN 1-55297-544-4..

- ^ Axelrod, Herbert, R. (1996). Exotic Tropical Fishes. T.F.H. Publications. ISBN 0-87666-543-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Griffith, Robert W.; et al. (1973). "Serum Composition of Freshwater Stingrays (Potamotrygonidae) Adapted to Fresh and Dilute Sea Water". Biological Bulletin. 144 (2): 304–320. doi:10.2307/1540010. JSTOR 1540010.

- ^ "Breeding of the raspy river stingray Potamotrygon scobina". 2003. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ^ "Des reproductions régulières en aquarium". Véronique Ivanov. 2009-01-05. Retrieved 31 August 2012.