Port Pirie

| Port Pirie South Australia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The lead smelter and grain silos at the wharf of Port Pirie | |||||||||

| Coordinates | 33°11′9″S 138°1′1″E / 33.18583°S 138.01694°E | ||||||||

| Population | 13,896[1] (2021 census) | ||||||||

| Established | 1845 | ||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 5540 | ||||||||

| Elevation | 4 m (13 ft) | ||||||||

| Time zone | ACST (UTC+9:30) | ||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | ACDT (UTC+10:30) | ||||||||

| Location | 223 km (139 mi) from Adelaide | ||||||||

| LGA(s) | Port Pirie Regional Council | ||||||||

| Region | Mid North | ||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Stuart[2] | ||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Grey[3] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

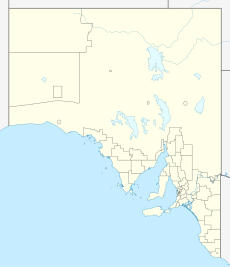

Port Pirie is a small city on the east coast of the Spencer Gulf in South Australia, 223 km (139 mi)[4] north of the state capital, Adelaide. Port Pirie is the largest city and the main retail centre of the Mid North region of South Australia. The city has an expansive history which dates back to 1845. Port Pirie was the first proclaimed regional city in South Australia, and is currently the second most important and second busiest port in SA.[5]

At the 2021 Census, Port Pirie had a population of 13,896.[1] Port Pirie is the eighth most populous city in South Australia after Adelaide, Mount Gambier, Gawler, Mount Barker, Whyalla, Murray Bridge and Port Lincoln.

The city's economy is dominated by one of the world's largest lead smelters,[6] operated by Nyrstar.[7] It also produces refined silver, copper, acid, gold and various other by-products.

In 2014, the smelter underwent a $650 million upgrade, of which $291 million was underwritten by the state government to replace some of the old existing plant and to reduce airborne lead emissions drastically.[8] Regardless of these upgrades, blood lead levels in young children continue to rise. In 2021 a report from the South Australian Health Department found an average blood level of 7.3 mg/dL in young children, compared to a finding of 5.3 mg/dL in 2014, and an upward trend of airborne lead levels.[9]

History

[edit]Prior to British settlement, the location that became Port Pirie was occupied by the indigenous tribe of Nukunu. The location was called 'Tarparrie', which is suspected to mean "Muddy Creek".[citation needed] The first European to see the location was Matthew Flinders in 1802, as he explored the Spencer Gulf by boat. The first land discovery of the location by a European was by the explorer Edward Eyre, who explored regions around Port Augusta. John Horrocks also discovered a pass through the Flinders Ranges to the coast, now named Horrocks Pass.[citation needed]

The town was originally called Samuel's Creek after the discovery of Muddy Creek by Samuel Germein. In 1846, Port Pirie Creek was named by Governor Robe after the John Pirie, the first vessel to navigate the creek when transporting sheep from Bowman's Run near Crystal Brook. In 1848, Matthew Smith and Emanuel Solomon bought 85 acres (34 ha) and subdivided it as a township to be known as Port Pirie. Little development occurred on site and by the late 1860s there were only three woolsheds on the riverfront.[10]

The locality was surveyed as a government town in December 1871 by Charles Hope Harris. The thoroughfares and streets were named after the family of George Goyder, Surveyor General of South Australia.[citation needed] In 1873, the land of Solomon and Smith was re-surveyed and named Solomontown. On 28 September 1876, with a population of 947, Port Pirie was declared a municipality.[11]

With the discovery of rich ore bearing silver, lead and zinc at Broken Hill in 1883, and the completion of a narrow gauge railway from Port Pirie to close to the Broken Hill field in 1888, the economic activities of the town underwent profound change. In 1889 a lead smelter was built by the British Blocks company to treat the Broken Hill ore. BHP initially leased the smelter from British Blocks but began constructing its own smelter from 1892. In 1913, the Russian consul-general Alexander Abaza reported that Port Pirie had a population of more than 500 Russians, mostly Ossetians, who had come to work at the smelter. At that time the town supported a Russian-language school and library.[12]

In 1915, the smelter was taken over by Broken Hill Associated Smelters (BHAS) – a joint venture of companies operating in Broken Hill. Led by the Collins House Group, by 1934 BHAS became the biggest lead smelter in the world.[13] The smelter gradually passed to Pasminco, then Zinifex, and since 2007 has been operated by Nyrstar.[14]

In 1921, the town's population had grown to 9,801, living in 2,308 occupied dwellings. By this date, there were 62 boarding houses to cater for the labour demands at the smelter, and the increasingly busy waterfront.[15]

During World War II (1941-1943), a Bombing and Gunnery school (2BAGS) was established by the Royal Air Force at Port Pirie. 22 men lost their lives there during training exercises. It was re-designated the 3 Aerial Observers School (3AOS) in December 1943.[16]

Port Pirie was declared South Australia's first provincial city in 1953, and today it is South Australia's second-largest port.[17]

Heritage listings

[edit]

The city is characterised by an attractive main street and some interesting and unusual historic buildings.[18] Heritage-listed sites include:

- 1 Alexander Street: Barrier Chambers Offices[19]

- 32 Ellen Street: Adelaide Steamship Company Building[20]

- 64-68 Ellen Street: Sampson's Butcher Shop[21]

- 69-71 Ellen Street: Port Pirie Customs House[22]

- 73-77 Ellen Street: Port Pirie (Ellen Street) railway station[23]

- 79-81 Ellen Street: Port Pirie Post Office[24]

- 85 Ellen Street: Development Board Building[25]

- 94 Ellen Street: Sample Rooms, rear of Portside Tavern[26]

- 134 Ellen Street: Family Hotel[27]

- 32 Florence Street: Carn Brae[28]

- 50-52 Florence Street: Waterside Workers' Federation Building[29]

- 105 Gertrude Street: Good Samaritan Catholic Convent School[30]

- Memorial Drive: Second World War Memorial Gates[31]

- 5 Norman Street: AMP Society Building, Port Pirie[32]

Demographics

[edit]In the 2021 census, the population of the Port Pirie urban area was 13,896 people. Approximately 51.0% of the population were female, 85.9% were Australian born, and 5.2% were Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people.

Port Pirie has significant Italian and Greek communities.

In 2021, the most popular industries for employment were copper, silver, lead and zinc smelting and refining (11.0%), non-psychiatric hospitals (6.0%), residential aged care (4.3%), other social assistance services (4.2%) and supermarket and grocery stores (3.9%). The unemployment rate was 7.7%. The median weekly household income was A$1044 per week. 48.5% of the population identified with no religion, while 21.0% identified themselves as Catholic.[1]

Geography

[edit]Port Pirie is at an elevation of 4 metres above sea level. It is approximately 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) inland, on the Pirie River, which is a tidal saltwater inlet from Spencer Gulf. It is on the coastal plain between Spencer Gulf to the west, and the Flinders Ranges to the east.

Climate

[edit]Port Pirie has a semi-arid climate (Köppen: BSh), with hot, dry summers and cool, somewhat wetter winters. The town is above Goyder's Line, and is surrounded by mallee scrub. Temperatures vary throughout the year, with average maxima ranging from 32.0 °C (89.6 °F) in January to 16.4 °C (61.5 °F) in July, and average minima fluctuating between 17.9 °C (64.2 °F) in February and 7.7 °C (45.9 °F) in July. Annual precipitation is low, averaging 345.9 mm (13.62 in), with a maximum in winter. There are 78.3 precipitation days, 125.0 clear days and 100.0 cloudy days annually. Extreme temperatures have ranged from 46.3 °C (115.3 °F) on 4 January 1979 to −1.7 °C (28.9 °F) on 27 June 1958.[33]

| Climate data for Port Pirie (33º10'12"S, 138º00'36"E, 2 m AMSL) (1877-2012 normals, extremes 1957-2012) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 46.3 (115.3) |

45.5 (113.9) |

42.5 (108.5) |

37.7 (99.9) |

31.0 (87.8) |

25.5 (77.9) |

26.5 (79.7) |

30.0 (86.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

39.5 (103.1) |

44.0 (111.2) |

44.6 (112.3) |

46.3 (115.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 32.0 (89.6) |

31.8 (89.2) |

29.4 (84.9) |

24.8 (76.6) |

20.4 (68.7) |

17.1 (62.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

18.1 (64.6) |

21.3 (70.3) |

24.5 (76.1) |

27.7 (81.9) |

30.0 (86.0) |

24.5 (76.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 17.7 (63.9) |

17.9 (64.2) |

16.0 (60.8) |

13.2 (55.8) |

10.7 (51.3) |

8.4 (47.1) |

7.7 (45.9) |

8.2 (46.8) |

9.8 (49.6) |

11.9 (53.4) |

14.4 (57.9) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.7 (54.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 4.4 (39.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

7.4 (45.3) |

4.8 (40.6) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

0.6 (33.1) |

0.3 (32.5) |

1.1 (34.0) |

1.1 (34.0) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 18.6 (0.73) |

17.8 (0.70) |

18.6 (0.73) |

27.5 (1.08) |

38.2 (1.50) |

40.7 (1.60) |

33.9 (1.33) |

34.9 (1.37) |

35.5 (1.40) |

33.3 (1.31) |

24.1 (0.95) |

23.0 (0.91) |

345.9 (13.62) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 3.1 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 5.3 | 8.3 | 10.2 | 10.6 | 10.6 | 8.1 | 6.9 | 5.2 | 4.1 | 78.3 |

| Average afternoon relative humidity (%) | 36 | 39 | 40 | 45 | 57 | 63 | 60 | 53 | 48 | 43 | 41 | 39 | 47 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 11.7 (53.1) |

11.9 (53.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

9.6 (49.3) |

9.8 (49.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

7.3 (45.1) |

6.7 (44.1) |

7.6 (45.7) |

7.8 (46.0) |

9.6 (49.3) |

10.6 (51.1) |

9.3 (48.8) |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology (1877-2012 normals, extremes 1957-2012)[34] | |||||||||||||

Transport

[edit]Port Pirie is 5 km (3 mi) off the Augusta Highway. It is serviced by Port Pirie Airport, six kilometres south of the city.

Railways

[edit]The first railway in Port Pirie opened in 1875 when the South Australian Railways 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) gauge Port Pirie-Cockburn line opened to Gladstone, ultimately being extended to Broken Hill.[35] The original Ellen Street station was located on the street with the track running down the middle.[36][37] The station today is occupied by the Port Pirie National Trust Museum.[38]

In 1937, it became a break-of-gauge station when the broad gauge Adelaide-Redhill line was extended to Port Pirie. At the same time the Commonwealth Railways standard gauge Trans-Australian Railway was extended south from Port Augusta to terminate at the new Port Pirie Junction station where it met the broad gauge line, in the suburb of Solomontown.[39][40]

As far back as 1943, a plan existed to build a new station to remove trains from Ellen Street.[41] As part of the gauge conversion of the Port Pirie to Broken Hill line, Mary Elie Street station was built to replace both Ellen Street and Port Pirie Junction stations.[42]

When opened, the new station was the meeting point for the Commonwealth Railways and South Australian Railways networks with through trains changing locomotives and crews, so the disadvantages were not as notable. However, after both became part of Australian National in July 1975 and trains began to operate in and out with the same locomotives, trains began to operate via Coonamia station on the outskirts of the city.

Mary Ellie Street station was eventually closed in the 1990s and in 2009 was redeveloped as the city's library. Until 2012, a GM class locomotive and three carriages were stabled at the platform.[43]

A freight line continues to operate into Port Pirie, feeding the metals plant with raw materials from Broken Hill, and transporting the processed material to Adelaide. This line is managed by Bowmans Rail.[44]

Sea transport

[edit]Port Pirie's marine facilities, managed by Flinders Ports, handle up to 100 ship visits annually, up to Handymax size, for commodities such as mineral concentrates, refined lead and zinc, coal, grain, and general cargo.[45]

Bridge to nowhere

[edit]

John Pirie Bridge, locally known as 'the bridge to nowhere', was built in the 1970s to encourage development of industry on the other side of Port Pirie Creek. Construction cost $410,000 and lasted 26 weeks. It was officially named the John Pirie Bridge in 1980. The land across the bridge remains undeveloped.[46]

Economy

[edit]The main industries are the smelting of metals, and the operation of silos to hold grain.

As of 2020[update], Port Pirie is the locality of the largest lead smelter and refinery in the southern hemisphere; a lead smelter has been there since the 1880s. The owner since 2007, Nyrstar, is the city's main employer.,[7] and high blood lead levels in the local population are an ongoing concern.[6] In 2006 Zinifex formed a joint venture with Umicore to create Nyrstar, which owns the smelter, with the intention that it would eventually be an entity separate from the parent companies.[47][48]

Waterfront development

[edit]The PPRC completed a major redevelopment of its foreshore area in 2014 including the construction of the Solomontown Beach Plaza, opening up Beach abroad to through traffic, replacing lighting along the beach and improving security.

Efforts to combat lead poisoning

[edit]Lead smelters contribute to several environmental problems, especially raised lead levels in the blood of some of the town population. The problem is particularly significant in many children who have grown up in the area. A state government project addressed this.[49][needs update] Nyrstar plans to progressively reduce lead in blood levels such that ultimately 95% of all children meet the national goal of 10 micrograms per decilitre. This has been known as the "tenby10" project. Community lead in blood levels in children are now at less than half the level that they were in the mid 1980s.[50]

The Port Pirie smelter conducted a project to reduce lead levels in children to less than 10 micrograms per decilitre by the end of 2010.[51][needs update]

"The goal we are committed to achieving is for at least 95% of our children aged 0 to 4 to have a blood lead level below ten micrograms per decilitre of blood (the first ten in tenby10) by the end of 2010" (the second ten in tenby10).[51]

Higher concentrations of lead have been found in the organs of bottlenose dolphins stranded near the lead smelter, compared to dolphins stranded elsewhere in South Australia.[52] The health impacts of these metals on dolphins has been examined and some associations between high metal concentrations and kidney toxicity were noted.[53]

Education

[edit]Port Pirie has many educational institutions, including John Pirie Secondary School[54] (years 7–12), St Mark's College[55] (Foundation - year 12), Mid North Christian College[56] (reception - year 12), many preschools and primary schools, and a TAFE campus (adult education).

Risdon Park High School (formerly Port Pirie Technical High School) was a co-ed state school.[57][58] In 1973, Port Pire Technical High School changed its name to Ridson Park High School,[57] and in 1995 the school merged with Port Pirie High School forming John Pirie Secondary School.[57]

Culture

[edit]

Port Pirie is home to the National Trust Historic and Folk Museum and Memorial Park,[citation needed] and the Port Pirie Regional Art Gallery also serves the regional community.[59]

Every September and October the city hosts a country music festival.

The Keith Michell Theatre, within the Northern Festival Centre, is named after the renowned actor Keith Michell, who grew up in Warnertown, 5 km (3 mi) from Port Pirie.[citation needed]

A play by actress and playwright Elena Carapetis, The Gods of Strangers, set in Port Pirie, is based on the oral histories of Greek, Cypriot and Italian people who migrated to regional South Australia after World War II. It was staged by the State Theatre Company South Australia in 2018.[60][61] It played at the Dunstan Playhouse in Adelaide as well as in Port Pirie. It was also filmed by local production company KOJO and intended to be shown by Country Arts SA in regional cinemas in 2020, but it was later shown online owing to the COVID-19 pandemic in South Australia.[62]

News media

[edit]The town's main newspaper, The Recorder, was first published 21 March 1885 as The Port Pirie Advocate and Areas News. In 1971, a brief experiment, known as the Northern Observer (7 July - 30 August 1971), occurred when The Recorder and The Transcontinental from Port Augusta were published under a combined title in Port Pirie.[63] The Recorder, which is still in print today (Tuesdays and Thursdays), has recently changed to a morning paper, after being delivered at around 3:00 pm.[64] Other Port Pirie newspapers include the free The Flinders News (Wednesdays), and The Advertiser, which covers some Port Pirie news, but to a very small extent.

Another newspaper, the Port Pirie Advertiser (7 April 1898 – 28 June 1924) was also published by Robert Osborne.[65] A further publication was the short-lived Saturday Times (6 December 1913 – 15 August 1914), printed by Roy Harold Butler and closed at the start of the Great War.[66]

Television coverage in the city is provided by the ABC, SBS, Southern Cross (7, 9 and 10) and Austar. Several radio stations cover Port Pirie, including ABC 639AM, ABC 891AM, 1044 5CS, 1242 5AU, ABC Classic FM, Radio National, ABC NewsRadio, triple j, Magic FM and Trax FM (a community radio station).

Governance

[edit]State and federal

[edit]| Port Pirie West State Elections | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006[67] | 2009[68] | ||

| Labor | 60.2% | 36.6% | |

| Liberal | 28.8% | 16.9% | |

| Family First | 5.7% | ||

| SA Greens | 3.4% | 2.6% | |

| Democrats | 1.9% | ||

| Geoff Brock | 40.9% | ||

| Nationals SA | 2.4% | ||

| One Nation | 0.5% | ||

| Port Pirie West 2007 Federal Election[69] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Labor | 58.79% | |

| Liberal | 28.02% | |

| Family First | 5.18% | |

| Greens | 4.29% | |

| National | 1.46% | |

| Democrats | 1.38% | |

| Independent | 0.89% | |

The results shown are from "Port Pirie West", the largest polling booth in Port Pirie, which is at the SA TAFE Campus.

Port Pirie is part of the federal division of Grey, and has been represented by Liberal MP Rowan Ramsey since 2007. Grey is held with a margin of 4.43% but is considered a safe Liberal seat.

The city is part of the state electoral district of Frome, which had been held since 1993 by former Liberal Premier, Rob Kerin, with a margin of 3.4%. It also has been considered a safe Liberal seat.

Although the region is generally Liberal-leaning because of its agricultural base, Port Pirie is an industrial centre that is favourable to the Australian Labor Party.

In late 2008, Rob Kerin announced his retirement, which led to a by-election being held in January 2009. Port Pirie mayor Geoff Brock announced his candidacy as an independent, and subsequently took the seat from the Liberals at the 2009 Frome by-election. After the poll for the by-election had closed and first preferences had been counted, (but before other preferences had been distributed), the result was LNP: 39.2%; ALP: 26.1%; Brock 23.6%; Nat: 6.6%; Greens: 3.8%; Other: 0.7%.[70][71]

State Opposition Leader Martin Hamilton-Smith (Liberal Party) claimed victory, prematurely.[72] Distribution of National Party, Greens and other preferences placed Brock ahead of the ALP candidate. Hence with the assistance of the ALP candidate's preferences, Geoff Brock won the by-election 51.7% to 48.3% for the Liberal candidate.[70][71]

Local government

[edit]Port Pirie and some of the sparsely inhabited areas around it are in the Port Pirie Regional Council local government area.

Notable residents

[edit]Sportspeople

[edit]- Brodie Atkinson (1972-), St. Kilda, Adelaide Crows, North Adelaide premiership player (1991), Sturt premiership player (2002) and Magarey Medal winner (1997)

- Mark Bickley (1969-), Adelaide Crows dual premiership captain

- Abby Bishop (1989-), Canberra Capitals basketball player

- Mark Jamar (1982-), Melbourne Demons player

- Lewis Johnston (1991-), Sydney Swans and Adelaide Crows football player

- Sam Mayes (1994-), North Adelaide, Brisbane Lions (2013-2018) and Port Adelaide FC (2019-) football player

- Nip Pellew (1893-1981), Australian test cricketer and North Adelaide player

- David Tiller (1958-), North Adelaide Roosters captain and premiership player

- Elijah Ware (1983-), Port Adelaide and Central Districts player and premiership player

Others

[edit]- Geoff Brock, state politician

- Sir Hugh Cairns (1896–1952), neurosurgeon

- Ted Connelly, state politician

- Lillian Crombie (1958–2024), actress[59]

- Andrew Lacey (1887–1946), federal and state politician, state leader of the ALP 1933–1938

- Keith Michell (1928-2015), actor

- John Noble (1948-), actor and director

- Robert Stigwood (1934-2016), music entrepreneur and impresario[73][74]

See also

[edit]- Category:People from Port Pirie

- Diocese of Willochra

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Port Pirie

- Sir John Pirie, 1st Baronet, for whom several places and features are named

- Nyrstar

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "2021 Port Pirie (Significant Urban Area), Census All persons QuickStats". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ "District of Stuart Background Profile". Electoral Commission SA. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Profile of the electoral division of Grey (SA)". Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ UBD South Australia and Northern Territory Country Road Atlas, 6th Edition, 2005. Universal Publishers Pty Ltd. ISBN 0 7319 1606 9

- ^ https://www.stateprosperity.sa.gov.au/upper-spencer-gulf

- ^ a b Port Pirie's lead smelter at risk of breaching licence to operate due to spike in lead levels ABC News, 8 November 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Port Pirie Overview". Nyrstar Limited. Archived from the original on 19 August 2006. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- ^ Port Pirie smelter could reopen old high-polluting sinter plant after new infrastructure damaged ABC News, 13 August 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ Port Pirie lead levels in two-year-olds hit 10-year high after Nyrstar's EPA licence breach ABC News, 22 February 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ Erik Eklund, Mining Towns: making a living, making a life, New South Publishing, Sydney, 2012, p. 137

- ^ https://www.aussietowns.com.au/town/port-pirie-sa

- ^ Massov, Alexander; Pollard, Marina; Windle, Kevin, eds. (2018). "Alexander Abaza" (PDF). A New Rival State?: Australia in Tsarist Diplomatic Communications. ANU Press. p. 304.

- ^ Eklund, Mining Towns, pp. 137-138.

- ^ https://www.nyrstar.com/operations/metals-processing/nyrstar-port-pirie

- ^ Eklund, Mining Towns, pp. 143-144.

- ^ "Port Pirie Air Force Commemorative Service". Air Force 100. 23 February 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ https://www.stateprosperity.sa.gov.au/upper-spencer-gulf

- ^ "Port Pirie", Travel section, smh.com.au, 17 February 2005. Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ "Barrier Chambers Offices". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Former Adelaide Steamship Company Building". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Dwelling (former Sampson's Butcher Shop)". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "National Trust Museum (former Port Pirie Customs House)". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "National Trust Museum (former Port Pirie Railway Station)". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Port Pirie Post Office". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Development Board Building (former Port Pirie Courthouse, later Customs House)". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Sample Rooms, rear of Jubilee (former Royal Exchange) Hotel". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Family Hotel". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Dwelling ('Carn Brae')". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Waterside Workers' Federation (former Amalgamated Workers' Association) Building". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Good Samaritan Catholic Convent School". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Second World War Memorial Gates". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Former AMP [Australian Mutual Provident Society] Port Pirie Office Building". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Port Pirie Nyrstar Comparison Climate (1877-2012)". FarmOnline Weather. Retrieved 10 August 2024.

- ^ "Port Pirie Climate Statistics (1877-2012)". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 10 August 2024.

- ^ Wilson, John, Port Pirie - The Narrow Gauge Era (1873–1935), Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin, March 1970, pp. 49–62

- ^ Bakewell, Guy and Wilson, John, Farewell to Ellen Street, Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin September 1968, pp. 210–213

- ^ Ward, Andrew (1982). Railway Stations of Australia. South Melbourne: MacMillan Company of Australia. pp. 60–61. ISBN 0-333338-53-7.

- ^ Port Pirie National Trust Museum Archived 9 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine Explore South Australia

- ^ Solomontown Railway Station Adelaide Advertiser 14 July 1937

- ^ Port Pirie Archived 28 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine National Railway Museum

- ^ Council Wants No Trains in Ellen Street The Recorder 31 March 1943

- ^ The Planning & Evaluation of Rail Standardisation Projects in Australia GR Webb 1976

- ^ Port Pirie Marie Elie Street Display Western Langford Railway Photography

- ^ "About Us - Bowman's Rail". www.bowmansrail.com.au. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016.

- ^ Access to Prime Infrastructure Port Pirie Regional Council. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ Ladgrove, Petria (7 December 2009). "Bridge To Nowhere". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ "Zinifex and Umicore seek to create the world's leading producer of zinc metal". Zinifex Limited. Australian Securities Exchange. 12 December 2006. Archived from the original on 25 March 2007. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- ^ "Zinifex, Umicore to combine zinc assets". The Age. 12 December 2006. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- ^ "Pt Pirie Environmental Health Centre". Retrieved 11 June 2006.

- ^ "Zinifex Port Pirie Strategy". Zinifex Limited. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- ^ a b "10 by Ten – 10 Ways To Have An Impact". www.tenby10.com. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ Lavery, T.J., Butterfield, N., Kemper, C.M., Reid, R.J., Sanderson, K. 2008. Metals and selenium in the liver and bone of three dolphin species from South Australia, 1988–2004. Science of the Total Environment, 390: 77–85

- ^ Lavery, T.J., Kemper, C.M., Sanderson, K., Schultz, C.G., Coyle, P., Mitchell, J.G., Seuront, L. 2008. Heavy metal toxicity of kidney and bone tissues in South Australian adult bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus), doi:10.1016/jmarenvres.2008.09.005

- ^ "Welcome to John Pirie Secondary School's website". www.johnpirihs.sa.edu.au. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ St Mark's College Archived 30 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Mid North Christian College - Port Pirie, SA - Home". www.midnorthcc.sa.edu.au. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ a b c "Risdon Park High School (S.A.) - Full record view - Libraries Australia Search". librariesaustralia.nla.gov.au. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ CARASS (14 March 2013). Proceedings of the Fifth International Congress on Mathematical Education. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4757-4238-1.

- ^ a b "Tribute - Lillian Crombie". Port Pirie Regional Council. 8 January 2024. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ McLean, CJ (17 November 2018). "Theatre Review: The Gods of Strangers". Glam Adelaide. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ Carapetis, Elena (17 January 2019). "The Gods Of Strangers". State Theatre Company. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ Marsh, Walter (19 June 2020). "The Gods of Strangers to return for online season". The Adelaide Review. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ Laube, Anthony. "LibGuides: SA Newspapers: M-N". guides.slsa.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ The Recorder - About Us Accessed 2 June 2013.

- ^ "Port Pirie advertiser". www.samemory.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ Laube, Anthony. "LibGuides: SA Newspapers: S". guides.slsa.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ Port Pirie West Polling Booth, District of Frome, House of Assembly Division First Preferences, 2006 State Election. Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ Port Pirie West Polling Booth Archived 25 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, District of Frome, House of Assembly Division First Preferences, 2009 By-election, 24 January 2009. Retrieved on 15 March 2009.

- ^ Port Pirie West Polling Booth, Division of Grey, House of Representatives Division First Preferences, 2007 Federal Election. Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ a b Frome 2009 By-election results, abc.net.au, 2 February 2009. Retrieved on 15 March 2009.

- ^ a b District of Frome - Electoral Results Archived 23 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Electoral Commission SA, 24 January 2009. Retrieved on 15 March 2009.

- ^ Libs claim Frome victory, AdelaideNow, 21 January 2009. Retrieved on 15 March 2009.

- ^ Late Port Pirie-raised music mogul Robert Stigwood who changed the entertainment world, The Advertiser, 5 January 2016. Accessed 6 January 2016.

- ^ Robert Stigwood, music mogul behind Bee Gees and Clapton, dies aged 81, ABC News, 5 January 2016. Accessed 6 January 2016.

External links

[edit]- Port Pirie, South Australia reference

- Port Pirie Regional Council

- "Port Pirie", Travel section, Sydney Morning Herald, 14 January 2008.

- "Port Pirie smelter changes from Zinifex to Nyrstar", ABC News, 31 August 2007.

- Nystar, Home page - English.