Port Augusta

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2015) |

| Port Augusta Goordnada South Australia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

View across Spencer Gulf to Mount Brown | |||||||||

| Coordinates | 32°29′33″S 137°45′57″E / 32.49250°S 137.76583°E | ||||||||

| Population | 12,788 (UCL 2021)[1] | ||||||||

| Established | 1852 | ||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 5700[2] | ||||||||

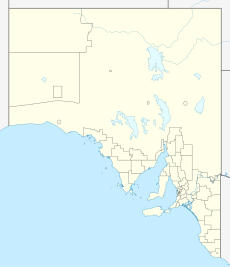

| Location |

| ||||||||

| LGA(s) | City of Port Augusta | ||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Stuart[3] Giles[4] | ||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Grey[5] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Port Augusta (Goordnada in the revived indigenous Barngarla language)[6] is a coastal city in South Australia about 310 kilometres (190 mi) by road from the state capital, Adelaide. Most of the city is on the eastern shores of Spencer Gulf, immediately south of the gulf's head,[7] comprising the city's centre and surrounding suburbs, Stirling North, and seaside homes at Commissariat Point, Blanche Harbor and Miranda.[8] The suburb of Port Augusta West is on the western side of the gulf on the Eyre Peninsula.[9] Together, these localities had a population of 13,515 people in the 2021 census.

Formerly a seaport, the city supports regional agriculture and services many mines in the South Australian interior to its north. A significant industry was electricity generation until 2019, when its coal-burning power stations were shut down. A solar farm opened in 2020.[10]

History

[edit]Port Augusta is part of Aboriginal Australians' Nukunu country, in which the local language is Barngarla. The last speaker of the language died in 1964, but successful efforts have been made to revive it based on a 3500-word dictionary compiled in the 1840s by German Lutheran pastor Clamor Wilhelm Schürmann.[6][11]: 230 Its original Barngarla name is Goordnada.[12]: 78

It is a natural harbour, which was proclaimed on 24 May 1852 by Alexander Elder (brother of Thomas Elder) and John Grainger, having discovered it while aboard the Government schooner Yatala, captained by Edward Dowsett.[13] The port was named after Augusta Sophia, Lady Young, the wife of the Governor of South Australia, Sir Henry Edward Fox Young. Lady Young was the daughter of Charles Marryat Snr., who had been a slaveholder in the British West Indies.[14][15] Her brother was the Anglican minister Dean of Adelaide Charles Marryat.

Flora and fauna

[edit]Marine species include resident species and migrating visitors. Occasional sightings are made of whales, sunfish, swordfish and turtles.[16][17][18][19]

Demographics

[edit]The city and its surrounds had a population of 13,515 people in the 2021 census. It was therefore the fourth largest urban area outside of Adelaide after Mount Gambier, Whyalla and Port Lincoln. 83.4% of residents were born in Australia and 20.8% were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. The most prevalent employment was community and personal service workers (17.7%), professionals (14.9%), technicians and trades workers (14.0%), labourers (13.1%), clerical and administrative workers (11.1%), sales workers (9.3%), machinery operators and drivers (9.3%), and managers (8.3%). The unemployment rate was 6.5% (South Australia: 5.4%). The median weekly household income was A$1277 per week.[20]

Transport

[edit]Port Augusta is at the head of Spencer Gulf, a natural barrier to land transport, leading to the city being considered to be the "crossroads of Australia", the junction of major road and rail links.[21]

Road

[edit]Port Augusta is located at the eastern end of the Eyre Highway to Perth and at the northern end of the Augusta Highway to Adelaide. It is situated at the southern end of the Stuart Highway to Darwin. Virtually all road traffic across southern Australia passes through Port Augusta across the top of Spencer Gulf.

Twice-daily coach services operate between Port Augusta, other country centres and Adelaide.[22]

Rail

[edit]

In 1878, the town became the southern terminus of a proposed north–south transcontinental line headed for Darwin 2500 km (1600 mi) away. As part of its commitments undertaken at Federation, the federal government took over this 1067 mm (3 ft 6 in) narrow gauge railway in 1911 and named it the "Central Australia Railway" in 1926. In 1929, it was extended to its last terminus at Alice Springs.[23]

Between 1913 and 1917, a 2000 km (1200 mi) long, east–west transcontinental railway, the Trans-Australian Railway, was built from Port Augusta to Kalgoorlie in Western Australia. It was built to 1435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge as part of a long-term plan to harmonise gauges between the mainland states. The choice created a break of gauge at Port Augusta until the standard gauge track was extended to Port Pirie in 1937. The last component of the all-through standard gauge line from Adelaide to Darwin was only completed in 2003.

Port Augusta is a stopping place of two long-distance "experiential" train services: the east-west Indian Pacific transcontinental service and The Ghan service between Adelaide and Darwin.

The not-for-profit Pichi Richi Railway, established in the 1970s on the southernmost section of the Central Australia Railway (CAR) at Quorn, was not connected to Port Augusta after the CAR closed in 1980. An ambitious project to build a line from Stirling North to the centre of Port Augusta was completed in 2001 and now provides half-day and full-day heritage railway journeys on selected dates from March to November.[24]

Aviation

[edit]Port Augusta Airport, 6 kilometres (4 miles) from the city, handles about 16,000 "fly-in fly-out" passengers a year who work at many mines in the north of South Australia. As of 2023[update], no other flights were available at the airport.[25]

Climate

[edit]Port Augusta has a hot desert climate (Köppen: BWh), with hot summers, mild winters and minimal precipitation year-round.[26][27] Some authors define it as hot semi-arid climate (BSh).[28][29] Temperatures vary throughout the year, with average maxima ranging from 34.1 °C (93.4 °F) in January to 18.0 °C (64.4 °F) in July, while average minima fluctuate between 19.5 °C (67.1 °F) in January and 4.6 °C (40.3 °F) in July. Mean annual rainfall is very low: 221.6 mm (8.72 in), spread between 72.2 precipitation days. There are 142.1 clear days and 92.4 cloudy days annually.[30] Extreme temperatures have ranged from −4.5 °C (23.9 °F) on 3 August 2014 to 49.5 °C (121.1 °F) on 24 January 2019.[31] Port Augusta has desert vegetation, although the city maintains with governmental aid with some plants adapted to aridity.[32] Port Augusta is regarded as a desert environment by the local government.[33]

| Climate data for Port Augusta (32º30'36"S, 137º43'12"E, 14 m AMSL) (2001-2024 normals and extremes, 3 pm humidity 1962-1997) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 49.5 (121.1) |

48.1 (118.6) |

43.1 (109.6) |

40.3 (104.5) |

32.2 (90.0) |

29.6 (85.3) |

26.9 (80.4) |

32.8 (91.0) |

38.4 (101.1) |

42.9 (109.2) |

46.3 (115.3) |

48.5 (119.3) |

49.5 (121.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 34.1 (93.4) |

33.1 (91.6) |

30.7 (87.3) |

26.6 (79.9) |

21.5 (70.7) |

18.1 (64.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.0 (68.0) |

24.1 (75.4) |

27.0 (80.6) |

30.0 (86.0) |

32.1 (89.8) |

26.3 (79.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 19.5 (67.1) |

18.8 (65.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

12.9 (55.2) |

8.6 (47.5) |

5.9 (42.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

5.4 (41.7) |

8.5 (47.3) |

11.9 (53.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

12.1 (53.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 11.7 (53.1) |

6.8 (44.2) |

6.6 (43.9) |

4.2 (39.6) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

−4 (25) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

6.9 (44.4) |

7.7 (45.9) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 15.3 (0.60) |

18.4 (0.72) |

11.9 (0.47) |

19.9 (0.78) |

16.4 (0.65) |

24.1 (0.95) |

15.8 (0.62) |

15.2 (0.60) |

18.3 (0.72) |

18.9 (0.74) |

21.7 (0.85) |

25.8 (1.02) |

221.6 (8.72) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 3.6 | 2.5 | 3.3 | 4.2 | 7.1 | 11.3 | 10.6 | 8.3 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 5.7 | 4.5 | 72.2 |

| Average afternoon relative humidity (%) | 36 | 36 | 39 | 41 | 48 | 53 | 51 | 45 | 40 | 37 | 35 | 37 | 42 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 11.5 (52.7) |

11.9 (53.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

7.6 (45.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

5.2 (41.4) |

4.3 (39.7) |

4.7 (40.5) |

6.0 (42.8) |

7.7 (45.9) |

10.1 (50.2) |

7.9 (46.2) |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology (2001-2024 normals and extremes, 3 pm humidity 1962-1997)[34][35] | |||||||||||||

Economy

[edit]Electricity generation

[edit]From the mid-1920s, the town was supplied with direct current electricity, which changed to alternating current in 1948.[36][37][38]

Electricity was generated at the Playford B (240 MW) and Northern power stations (520 MW) from brown coal mined at Leigh Creek, 250 km to the north. The only coal-fired electricity generating plants in South Australia, in 2009 they produced 33% of the state's electricity, but over 50% of the state's CO2 emissions from electricity generation.[39]

Playford B has not been operational since 2012. In October 2015, Alinta Energy announced the permanent closure of both Northern and Playford B in early 2016. The Northern Power Station went offline in May 2016.[40][41]

In 2016, a local community group was lobbying for assistance to replace the coal-fired plants with a solar thermal power station.[42] The premier of South Australia, Jay Weatherill announced in August 2017 that construction would begin in 2018 and was expected to be completed in 2020. The Aurora Solar Thermal Power Project is expected to cost A$650M to build, including a A$110M loan from the Federal Government, and deliver 150MW of electricity. SolarReserve has a contract to supply all of the electricity required by the state government's offices from this power project.[43][needs update]

Arid-zone horticulture

[edit]Separately, Sundrop Farms has a combined solar power tower, greenhouse and desalination plant which is used to produce tomatoes near the old power station site.[44] It opened in October 2016 and produces 39MW of thermal energy from over 23,000 mirrors and a 127 metres (417 ft) tower, used for heating, electricity, and desalination to irrigate tomatoes in greenhouses. Sundrop has a 10-year contract to supply Coles Supermarkets with at least 15,000 tonnes of truss tomatoes per year.[45]

Tourism

[edit]Port Augusta has been able to capitalise on the growing eco-tourism industry due to its proximity to the Flinders Ranges. The Pichi Richi Railway is a major drawcard, connecting Port Augusta to Quorn via the Pichi Richi Pass.

Within Port Augusta is the City of Port Augusta's Wadlata Outback Centre, providing tourists with an introduction to life in the Australian outback. The centre recorded over 500,000 visitors in 2006. North of the town, on the Stuart Highway, is the Australian Arid Lands Botanic Garden, a unique and award-winning garden, opened in 1996, which "showcases a diverse collection of arid zone habitats in a picturesque setting of more than 250 hectares".[46] The gardens have a cafe/restaurant with views across the saltbush plains to the escarpment of the Flinders Ranges. The PACC annual report shows more than 100,000 people visited the gardens in 2006.

Southwest of town is the El-Alamein army base.

Proposed multi-commodity port

[edit]In February 2019, the site of the former Playford power stations was sold by Alinta Energy to Cu-River Mining as a prospective port development site. The company intended to construct a transshipment facility suitable for the export of iron ore, wheat and other commodities.[47][needs update]

Media

[edit]The major publication of the town is The Transcontinental, a weekly newspaper that was first issued in October 1914 and continues to be located on Commercial Road. In 1971, a brief experiment, known as the Northern Observer (7 July 1971 – 30 August 1971), occurred when The Transcontinental and The Recorder from Port Pirie were published under a combined title in Port Pirie.[48]

Historically, the town published the Dispatch (1877–1916), which, as was common at the time, evolved through a series of name changes: Port Augusta Dispatch (18 August 1877 – 6 August 1880);[49] Port Augusta Dispatch and Flinders' Advertiser (13 August 1880 – 17 October 1884); Port Augusta Dispatch (20 October 1884 – 16 March 1885); and, Port Augusta Dispatch, Newcastle and Flinders Chronicle (18 March 1885 – 21 April 1916). For a short period, due to the short-lived discovery of gold at Teetulpa, a sister publication Teetulpa News and Golden Age (1886–1887) was printed by the Dispatch.[50]

Another publication, the Port Augusta and Stirling Illustrated News (1901), was printed briefly in the town by James Taylor, but was curtailed so he could focus on his printing business.[51]

Politics

[edit]State and federal

[edit]| 2006 state election[52] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Labor | 62.3% | |

| Liberal | 30.7% | |

| Family First | 3.0% | |

| Greens | 2.3% | |

| Democrats | 1.3% | |

| Independent | 0.3% | |

| 2007 federal election[53] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Labor | 53.99% | |

| Liberal | 31.4% | |

| Family First | 4.47% | |

| Greens | 3.86% | |

| National | 3.32% | |

| Independent | 1.69% | |

| Democrats | 1.27% | |

| 2022 federal election[54] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Liberal | 32.23% | |

| Labor | 30.86% | |

| Independent (Habermann) | 11.52% | |

| Greens | 8.59% | |

| One Nation | 6.45% | |

| United Australia Party | 5.66% | |

| Australian Federation Party | 2.34% | |

| Independent (Carmody) | 1.76% | |

| Liberal Democrats | 0.59% | |

Since the 2020 redistribution, Port Augusta was split between the state electoral district of Stuart and electoral district of Giles. In federal politics, the city is part of the division of Grey, and has been represented by Liberal MP Rowan Ramsey since 2007. Grey is held with a margin of 8.86% and is considered safe-liberal. The results shown are from the largest polling station in Port Augusta – which is located at Port Augusta TAFE college.

Local

[edit]Port Augusta is in the City of Port Augusta local government area. The City of Port Augusta is believed to have had the longest serving mayor in Australia, Joy Baluch, who died after 30 years of service on 14 May 2013.[citation needed][55] The council is based at the Port Augusta Civic Centre; prior to 1983, it operated out of the now-disused Port Augusta Town Hall.

Heritage listings

[edit]Port Augusta has a number of heritage-listed sites, including:

- Beauchamp Lane: Port Augusta Waterworks[56]

- Beauchamp Lane: Beatton Memorial Drinking Fountain[57]

- Beauchamp Lane: Gladstone Square Bandstand[58]

- 9 Church Street: St Augustine's Anglican Church, Port Augusta[59]

- Commercial Road: Old Port Augusta railway station[60]

- 52 Commercial Road: Port Augusta Institute[61]

- 54 Commercial Road: Port Augusta Town Hall[62]

- 34 Flinders Terrace: Port Augusta School of the Air[63]

- 1 Jervois Street: Port Augusta Courthouse[64]

- Stirling Street: Port Augusta railway station[65]

- off Tassie Street: Port Augusta Wharf[66]

- 12 Tassie Street: Bank of South Australia, Port Augusta[67]

See also

[edit]- Point Paterson Desalination Plant

- The Sundowners (1960), partly filmed on location in Port Augusta[68][self-published source?]

- List of extreme temperatures in Australia

References

[edit]- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Port Augusta (urban centre and locality)". Australian Census 2021.

- ^ Australia Post – Postcode: Port Augusta, SA (26 June 2008)

- ^ "District of Stuart Background Profile". Electoral Commission SA. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "District of Giles Background Profile". Electoral Commission SA. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Profile of the electoral division of Grey (SA)". Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ a b Hamilton, Jodie (26 June 2021). "Kindy kids learning Barngarla Indigenous language, spread joy as they talk". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Cat. No. 3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2011 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Accessed 10 August 2012.

- ^ "Journey through time". Port Augusta City Council. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ Boating Industry Association of South Australia (BIA); South Australia. Department for Environment and Heritage (2005), South Australia's waters an atlas & guide, Boating Industry Association of South Australia, p. 209, ISBN 978-1-86254-680-6

- ^ Parkinson, Giles (11 September 2020). "South Australia's biggest solar farm finally moves to full production". RenewEconomy. Archived from the original on 11 September 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2020), Revivalistics: From the Genesis of Israeli to Language Reclamation in Australia and Beyond, Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199812790 / ISBN 9780199812776

- ^ Zuckermann, Ghil'ad and the Barngarla (2019), Barngarlidhi Manoo (Speaking Barngarla Together), Barngarla Language Advisory Committee. (Barngarlidhi Manoo – Part II)

- ^ "SA Memory: Port Augusta". State Library of South Australia. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ Coventry, CJ (2019). "Links in the Chain: British slavery, Victoria and South Australia". Before/Now. 1 (1). doi:10.17613/d8ht-p058.

- ^ "Charles Marryat". Legacies of British Slave-ownership database. University College London. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ "Baby turtle caught at Port Augusta". Port Lincoln Times (SA : 1927 - 1954). 19 November 1942. p. 4. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ "PORT AUGUSTA, June 6". South Australian Chronicle and Weekly Mail (Adelaide, SA : 1868 - 1881). 13 June 1868. p. 7. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ "PORT AUGUSTA, FEBRUARY 4". South Australian Advertiser (Adelaide, SA : 1858 - 1889). 12 February 1870. p. 3. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ "PORT AUGUSTA, SEP. 15". Bunyip (Gawler, SA : 1863 - 1954). 17 September 1880. p. 3. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). 4004 "Port Augusta (Significant Urban Areas)". 2021 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Attractions". Port Augusta City Council. 24 September 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ "Whyalla - Port Augusta - Port Pirie - Adelaide Timetable" (PDF). Stateliner. 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ Babbage, Jack; Barrington, Rodney (1984). The history of Pichi Richi Railway. Quorn, South Australia: Pichi Richi Railway Preservation Society Inc. p. 11. ISBN 0959850961.

- ^ "Heritage railway operating since 1878". Pichi Richi Railway. 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ "Port Augusta Airport". Port Augusta City Council. 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ Specht, R. L.; Rundel, P. W.; Westman, W. E.; Catling, P. C.; Majer, J. D.; Greenslade, P. (6 December 2012). Mediterranean-type Ecosystems: A data source book. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 98. ISBN 978-94-009-3099-5.

- ^ "Port Augusta climate: Average Temperature, weather by month, Port Augusta weather averages - Climate-Data.org". en.climate-data.org. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ Rickard, Simon (2011). The New Ornamental Garden. Csiro Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-643-09596-0.

- ^ "Port Augusta, South Australia Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ "Port Augusta Power Station Climate (1958-1997)". FarmOnline Weather. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Port Augusta Aero Climate (2001-2024)". FarmOnline Weather. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Bush garden battling a crippling cash drought for desert garden". www.adelaidenow.com.au. 21 June 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ "NOTICE OF AUSTRALIAN ARID LANDS BOTANIC GARDEN ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ "Port Augusta Aero Climate Statistics (2001-2024)". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Port Augusta Power Station Climate Statistics (1958-1997)". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "ELECTRIC LIGHT FOR PORT AUGUSTA". Advertiser (Adelaide, SA : 1889 - 1931). 30 March 1923. p. 8. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Port Augusta Proceeding With Power Changeover". Chronicle (Adelaide, SA : 1895 - 1954). 8 July 1948. p. 9. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Advertising". Transcontinental (Port Augusta, SA : 1914 - 1954). 2 April 1948. p. 3. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ The Climate Group Greenhouse Indicator Series: Electricity Generation Report 2009 Archived 8 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ SA's coal era ends, but what's next? InDaily, 9 May 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^ End of an era: final day of coal-fired power generation in Port Augusta ABC News, 9 May 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^ Michael Slezak (23 March 2016). "Port Augusta 'busting a gut' to reinvent itself as a solar city when coal-fired power is switched off". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ "Solar thermal power plant announced for Port Augusta 'biggest of its kind in the world'". ABC News. 14 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ Fairfax Regional Media (24 March 2016). "Solar tower reaches new heights". The Transcontinental. Retrieved 24 March 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Staight, Kerry (2 October 2016). "Sundrop Farms pioneering solar-powered greenhouse to grow food without fresh water". Landline. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ "About the Garden". Australian Arid Lands Botanic Garden. Australian Arid Lands Botanic Garden. 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Candice Prosser (1 February 2019). "Shipping to return to Port Augusta with new port project". ABC News. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ Laube, Anthony. "LibGuides: SA Newspapers: M-N". guides.slsa.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ "Port Augusta Dispatch (SA : 1877 – 1880)". Trove. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ Laube, Anthony. "LibGuides: SA Newspapers: T-Z". guides.slsa.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Laube, Anthony. "LibGuides: SA Newspapers: O-R". guides.slsa.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ Port Augusta West Polling Booth Archived 15 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, District of Stuart, House of Assembly Division First Preferences, 2006 State Election. Retrieved on 26 June 2008.

- ^ Port Augusta East Polling Booth, Division of Grey, House of Representatives Division First Preferences, 2007 Federal Election. Retrieved on 26 June 2008.

- ^ "Port Augusta East - polling place". Australian Electoral Commission Tally Room 2022. 27 May 2022. Archived from the original on 24 June 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ Outspoken Port Augusta Mayor Joy Baluch dies after breast cancer battle adelaidenow (News Ltd.) Accessed 17 May 2013.

- ^ "Former Port Augusta Waterworks workshop, storeroom, stables and courtyard". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Beatton Memorial Drinking Fountain, Gladstone Square". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Gladstone Square Bandstand". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "St Augustine's Anglican Church". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Curdnatta Art Gallery (former first Port Augusta Railway Station)". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Port Augusta Institute". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Port Augusta Town Hall". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Former Port Augusta School of the Air". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Port Augusta Courthouse". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Second Port Augusta Railway Station". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Port Augusta Wharf". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Seaview House (former Bank of South Australia Port Augusta Branch)". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 February 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "America's Best, Britain's Finest: A Survey of Mixed Movies" – Google Books, John Howard Reid, pub. Lulu.com, March 2006. ISBN 9781411678774, p. 241[self-published source]