Home Army

| Home Army | |

|---|---|

| Armia Krajowa (AK) | |

Polish red-and-white flag with superposed Kotwica (lit. 'anchor') emblem of the Polish Underground State and Home Army | |

| Active | 14 February 1942 – 19 January 1945 |

| Country | German-occupied Poland |

| Allegiance | Polish government-in-exile |

| Role | Armed forces of the Polish Underground State |

| Size | c. 400,000 (1944) |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Tadeusz Komorowski Stefan Rowecki Leopold Okulicki Emil August Fieldorf Antoni Chruściel |

The Home Army (Polish: Armia Krajowa, pronounced [ˈarmja kraˈjɔva]; abbreviated AK) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) established in the aftermath of the German and Soviet invasions in September 1939. Over the next two years, the Home Army absorbed most of the other Polish partisans and underground forces. Its allegiance was to the Polish government-in-exile in London, and it constituted the armed wing of what came to be known as the Polish Underground State. Estimates of the Home Army's 1944 strength range between 200,000 and 600,000. The latter number made the Home Army not only Poland's largest underground resistance movement but, along with Soviet and Yugoslav partisans, one of Europe's largest World War II underground movements.[a]

The Home Army sabotaged German transports bound for the Eastern Front in the Soviet Union, destroying German supplies and tying down substantial German forces. It also fought pitched battles against the Germans, particularly in 1943 and in Operation Tempest from January 1944. The Home Army's most widely known operation was the Warsaw Uprising of August–October 1944. The Home Army also defended Polish civilians against atrocities by Germany's Ukrainian and Lithuanian collaborators. Its attitude toward Jews remains a controversial topic.

As Polish–Soviet relations deteriorated, conflict grew between the Home Army and Soviet forces. The Home Army's allegiance to the Polish government-in-exile caused the Soviet government to consider the Home Army to be an impediment to the introduction of a communist-friendly government in Poland, which hindered cooperation and in some cases led to outright conflict. On 19 January 1945, after the Red Army had cleared most Polish territory of German forces, the Home Army was disbanded. After the war, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s, communist government propaganda portrayed the Home Army as an oppressive and reactionary force. Thousands of ex-Home Army personnel were deported to gulags and Soviet prisons, while other ex-members, including a number of senior commanders, were executed. After the fall of communism in Central and Eastern Europe, the portrayal of the Home Army was no longer subject to government censorship and propaganda.

Origins

| Part of a series on the |

| Polish Underground State |

|---|

|

The Home Army originated in the Service for Poland's Victory (Służba Zwycięstwu Polski), which General Michał Karaszewicz-Tokarzewski set up on 27 September 1939, just as the coordinated German and Soviet invasions of Poland neared completion.[1] Seven weeks later, on 17 November 1939, on orders from General Władysław Sikorski, the Service for Poland's Victory was superseded by the Armed Resistance (Związek Walki Zbrojnej), which in turn, a little over two years later, on 14 February 1942, became the Home Army.[1][2] During that time, many other resistance organisations remained active in Poland,[3] although most of them, merged with the Armed Resistance or with its successor, the Home Army, and substantially augmented its numbers between 1939 and 1944.[2][3]

The Home Army was loyal to the Polish government-in-exile and to its agency in occupied Poland, the Government Delegation for Poland (Delegatura). The Polish civilian government envisioned the Home Army as an apolitical, nationwide resistance organisation. The supreme command defined the Home Army's chief tasks as partisan warfare against the German occupiers, the re-creation of armed forces underground and, near the end of the German occupation, a general armed rising to be prosecuted until victory. Home Army plans envisioned, at war's end, the restoration of the pre-war government following the return of the government-in-exile to Poland.[4][1][2][5][6][7]

The Home Army, though in theory subordinate to the civil authorities and to the government-in-exile, often acted somewhat independently, with neither the Home Army's commanders in Poland nor the "London government" fully aware of the other's situation.[8]: 235–236

After Germany started its invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, the Soviet Union joined the Allies and signed the Anglo-Soviet Agreement on 12 July 1941. This put the Polish government in a difficult position since it had previously pursued a policy of "two enemies". Although a Polish–Soviet agreement was signed in August 1941, cooperation continued to be difficult and deteriorated further after 1943 when Nazi Germany publicised the Katyn massacre of 1940.[9]

Until the major rising in 1944, the Home Army concentrated on self-defense (the freeing of prisoners and hostages, defense against German pacification operations) and on attacks against German forces. Home Army units carried out thousands of armed raids and intelligence operations, sabotaged hundreds of railway shipments, and participated in many partisan clashes and battles with German police and Wehrmacht units. The Home Army also assassinated prominent Nazi collaborators and Gestapo officials in retaliation against Nazi terror inflicted on Poland's civilian population; prominent individuals assassinated by the Home Army included Igo Sym (1941) and Franz Kutschera (1944).[1][5]

Membership

Size

In February 1942, when the Home Army was formed from the Armed Resistance, it numbered around 100,000 members.[5] Less than a year later, at the start of 1943, it had reached a strength of around 200,000.[5] In the summer of 1944, when Operation Tempest began, the Home Army reached its highest membership:[5] estimates of membership in the first half and summer of 1944 range from 200,000,[8]: 234 through 300,000,[10] 380,000[5] and 400,000[11] to 450,000–500,000,[12] though most estimates average at about 400,000; the strength estimates vary due to the constant integration of other resistance organisations into the Home Army, and that while the number of members was high and that of sympathizers was even higher, the number of armed members participating in operations at any given time was smaller—as little as one per cent in 1943, and as many as five to ten per cent in 1944[11]—due to an insufficient number of weapons.[5][13][8]: 234

Home Army numbers in 1944 included a cadre of over 10,000–11,000 officers, 7,500 officers-in-training (singular: podchorąży) and 88,000 non-commissioned officers (NCOs).[5] The officer cadre was formed from prewar officers and NCOs, graduates of underground courses, and elite operatives usually parachuted in from the West (the Silent Unseen).[5] The basic organizational unit was the platoon, numbering 35–50 people, with an unmobilized skeleton version of 16–25; in February 1944, the Home Army had 6,287 regular and 2,613 skeleton platoons operational.[5] Such numbers made the Home Army not only the largest Polish resistance movement, but one of the two largest in World War II Europe.[a] Casualties during the war are estimated at 34,000[10] to 100,000,[5] plus some 20,000[10]–50,000[5] after the war (casualties and imprisonment).

Demographics

The Home Army was intended to be a mass organisation that was founded by a core of prewar officers.[5] Home Army soldiers fell into three groups. The first two consisted of "full-time members": undercover operatives, living mostly in urban settings under false identities (most senior Home Army officers belonged to this group); and uniformed (to a certain extent) partisans, living in forested regions (leśni, or "forest people"), who openly fought the Germans (the forest people are estimated at some 40 groups, numbering 1,200–4,000 persons in early 1943, but their numbers grew substantially during Operation Tempest).[8]: 234–235 The third, largest group were "part-time members": sympathisers who led "double lives" under their real names in their real homes, received no payment for their services, and stayed in touch with their undercover unit commanders but were seldom mustered for operations, as the Home Army planned to use them only during a planned nationwide rising.[8]: 234–235

The Home Army was intended to be representative of the Polish nation, and its members were recruited from most parties and social classes.[8]: 235–236 Its growth was largely based on integrating scores of smaller resistance organisations into its ranks; most of the other Polish underground armed organizations were incorporated into the Home Army, though they retained varying degrees of autonomy.[2] The largest organization that merged into the Home Army was the leftist Peasants' Battalions (Bataliony Chłopskie) around 1943–1944,[14] and parts of the National Armed Forces (Narodowe Siły Zbrojne) became subordinate to the Home Army.[15] In turn, individual Home Army units varied substantially in their political outlooks, notably in their attitudes toward ethnic minorities and toward the Soviets.[8]: 235–236 The largest group that completely refused to join the Home Army was the pro-Soviet, communist People's Army (Armia Ludowa), which numbered 30,000 people at its height in 1944.[16]

Women

Home Army ranks included a number of female operatives.[17] Most women worked in the communications branch, where many held leadership roles or served as couriers.[18] Approximately a seventh to a tenth of the Home Army insurgents were female.[19][18][20]

Notable women in the Home Army included Elżbieta Zawacka, an underground courier who was sometimes called the only female Cichociemna.[21] Grażyna Lipińska organised an intelligence network in German-occupied Belarus in 1942–1944.[22][23] Janina Karasiówna and Emilia Malessa were high-ranking officers described as "holding top posts" within the communication branch of the organisation.[18] Wanda Kraszewska-Ancerewicz headed the distribution branch.[18] Several all-female units existed within the AK structures, including Dysk, an entirely female sabotage unit led by Wanda Gertz, who carried out assassinations of female Gestapo informants in addition to sabotage.[18][24] During the Warsaw Uprising, two all-female units were created—a demolition unit and a sewer system unit.[19]

Many women participated in the Warsaw Uprising, particularly as medics or scouts;[25][26][19] they were estimated to form about 75% of the insurgent medical personnel.[20] By the end of the uprising, there were about 5,000 female casualties among the insurgents, with over 2,000 female soldiers taken captive; the latter number reported in contemporary press caused a "European sensation".[18]

Structure

Home Army Headquarters was divided into five sections, two bureaus and several other specialized units:[1][5][27]

- Section I: Organization – personnel, justice, religion

- Section II: Intelligence and Counterintelligence

- Section III: Operations and Training – coordination, planning, preparation for a nationwide uprising

- Section IV: Logistics

- Section V: Communication – including with the Western Allies; air drops

- Bureau of Information and Propaganda (sometimes called "Section VI") – information and propaganda

- Bureau of Finances (sometimes called "Section VII") – finances

- Kedyw (acronym for Kierownictwo Dywersji, Polish for "Directorate of Diversion") – special operations

- Directorate of Underground Resistance

The Home Army's commander was subordinate in the military chain of command to the Polish Commander-in-Chief (General Inspector of the Armed Forces) of the Polish government-in-exile and answered in the civilian chain of command to the Government Delegation for Poland.[5][4]

The Home Army's first commander, until his arrest by the Germans in 1943, was Stefan Rowecki (nom de guerre "Grot", "Spearhead"). Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski (Tadeusz Komorowski, nom de guerre "Bór", "Forest") commanded from July 1943 until his surrender to the Germans when the Warsaw Uprising was suppressed in October 1944. Leopold Okulicki, nom de guerre Niedzwiadek ("Bear"), led the Home Army in its final days.[1][28][29][30]

| Home Army commander | Codename | Period | Replaced because | Fate | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Michał Karaszewicz-Tokarzewski Technically, commander of Służba Zwycięstwu Polski and Związek Walki Zbrojnej as Armia Krajowa was not named such until 1942 |

Torwid | 27 September 1939 – March 1940 | Arrested by the Soviets | Joined the Anders Army, fought in the Polish Armed Forces in the West. Emigrated to United Kingdom. |

|

| General Stefan Rowecki | Grot | 18 June 1940 – 30 June 1943 | Discovered and arrested by German Gestapo | Imprisoned in Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Executed by personal decree of Heinrich Himmler after Warsaw Uprising had begun. |

|

| General Tadeusz Komorowski | Bór | July 1943 – 2 September 1944 | Surrendered after end of Warsaw Uprising. | Emigrated to United Kingdom. |

|

| General Leopold Okulicki | Niedźwiadek | 3 October 1944 – 17 January 1945 | Dissolved AK trying to lessen the Polish-Soviet tensions. | Arrested by the Soviets, sentenced to imprisonment in the Trial of the Sixteen. Likely executed in 1946. |

|

Regions

The Home Army was divided geographically into regional branches or areas (obszar),[1] which were subdivided into subregions or subareas (podokręg) or independent areas (okręgi samodzielne). There were 89 inspectorates (inspektorat) and 280 (as of early 1944) districts (obwód) as smaller organisational units.[5] Overall, the Home Army regional structure largely resembled Poland's interwar administration division, with an okręg being similar to a voivodeship (see Administrative division of Second Polish Republic).[5]

There were three to five areas: Warsaw (Obszar Warszawski, with some sources differentiating between left- and right-bank areas – Obszar Warszawski prawo- i lewobrzeżny), Western (Obszar Zachodni, in the Pomerania and Poznań regions), and Southeastern (Obszar Południowo-Wschodni, in the Lwów area); sources vary on whether there was a Northeastern Area (centered in Białystok – Obszar Białystocki) or whether Białystok was classified as an independent area (Okręg samodzielny Białystok).[31]

| Area | Districts | Codenames | Units (re)created during the reconstruction of the Polish Army in Operation Tempest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warsaw area Codenames: Cegielnia (Brickworks), Woda (Water), Rzeka (River) Warsaw Col. Albin Skroczyński Łaszcz |

Eastern Warsaw-Praga Col. Hieronim Suszczyński Szeliga |

Struga (stream), Krynica (source), Gorzelnia (distillery) | 10th Infantry Division |

| Western Warsaw Col. Franciszek Jachieć Roman |

Hallerowo (Hallertown), Hajduki, Cukrownia (Sugar factory) | 28th Infantry Division | |

| Northern Warsaw Lt. Col. Zygmunt Marszewski Kazimierz |

Olsztyn, Tuchola, Królewiec, Garbarnia (tannery) | 8th Infantry Division | |

| Southeastern area Codenames: Lux, Lutnia (Lute), Orzech (Nut) Lwów Col. Władysław Filipkowski Janka |

Lwów Lwów – divided into two areas Okręg Lwów Zachód (West) and Okręg Lwów Wschód (East) Col. Stefan Czerwiński Luśnia |

Dukat (ducat), Lira (lire), Promień (ray) | 5th Infantry Division |

| Stanisławów Stanisławów Capt. Władysław Herman Żuraw |

Karaś (crucian carp), Struga (stream), Światła (lights) | 11th Infantry Division | |

| Tarnopol Tarnopol Maj. Bronisław Zawadzki |

Komar (mosquito), Tarcza (shield), Ton (tone) | 12th Infantry Division | |

| Western area Codename: Zamek (Castle) Poznań Col. Zygmunt Miłkowski Denhoff |

Pomerania Gdynia Col. Janusz Pałubicki Piorun |

Borówki (berries), Pomnik (monument) | |

| Poznań Poznań Col. Henryk Kowalówka |

Pałac (palace), Parcela (lot) | ||

| Independent areas | Wilno Wilno Col. Aleksander Krzyżanowski Wilk |

Miód (honey), Wiano (dowry) (subunit "Kaunas Lithuania") | |

| Nowogródek Nowogródek Lt.Col. Janusz Szlaski Borsuk |

Cyranka (garganey), Nów (new moon) | Zgrupowanie Okręgu AK Nowogródek | |

| Warsaw Warsaw Col. Antoni Chruściel Monter |

Drapacz (sky-scraper), Przystań (harbour), Wydra (otter), Prom (shuttle) |

||

| Polesie Pińsk Col. Henryk Krajewski Leśny |

Kwadra (quarter), Twierdza (keep), Żuraw (crane) | 30th Infantry Division | |

| Wołyń Równe Col. Kazimierz Bąbiński Luboń |

Hreczka (buckwheat), Konopie (hemp) | 27th Infantry Division | |

| Białystok Białystok Col. Władysław Liniarski Mścisław |

Lin (tench), Czapla (aigrette), Pełnia (full moon) | 29th Infantry Division | |

| Lublin Lublin Col. Kazimierz Tumidajski Marcin |

Len (linnen), Salon (saloon), Żyto (rye) | 3rd Legions' Infantry Division 9th Infantry Division | |

| Kraków Kraków various commanders, incl. Col. Julian Filipowicz Róg |

Gobelin, Godło (coat of arms), Muzeum (museum) | 6th Infantry Division 106th Infantry Division 21st Infantry Division 22nd Infantry Division 24th Infantry Division Kraków Motorized Cavalry Brigade | |

| Silesia Katowice various commanders, incl. Col. Zygmunt Janke Zygmunt |

Kilof (pick), Komin (chimney), Kuźnia (foundry), Serce (heart) | ||

| Kielce-Radom Kielce, Radom Col. Jan Zientarski Mieczysław |

Rolnik (farmer), Jodła (fir) | 2nd Legions' Infantry Division 7th Infantry Division | |

| Łódź Łódź Col. Michał Stempkowski Grzegorz |

Arka (ark), Barka (barge), Łania (bath) | 25th Infantry Division 26th Infantry Division | |

| Foreign areas | Hungary Budapest Lt.Col. Jan Korkozowicz |

Liszt | |

| Reich Berlin |

Blok (block) |

In 1943 the Home Army began recreating the organization of the prewar Polish Army, its various units now being designated as platoons, battalions, regiments, brigades, divisions, and operational groups.[5]

Operations

Intelligence

The Home Army supplied valuable intelligence to the Allies; 48 per cent of all reports received by the British secret services from continental Europe between 1939 and 1945 came from Polish sources.[32] The total number of those reports is estimated at 80,000, and 85 per cent of them were deemed to be high quality or better.[33] The Polish intelligence network grew rapidly; near the end of the war, it had over 1,600 registered agents.[32]

The Western Allies had limited intelligence assets in Central and Eastern Europe. The extensive in-place Polish intelligence network proved a major resource; between the French capitulation and other Allied networks that were undeveloped at the time, it was even described as "the only [A]llied intelligence assets on the Continent".[34][35][32] According to Marek Ney-Krwawicz, for the Western Allies, the intelligence provided by the Home Army was considered to be the best source of information on the Eastern Front.[36]

Home Army intelligence provided the Allies with information on German concentration camps and the Holocaust in Poland (including the first reports on this subject received by the Allies[37][38]), German submarine operations, and, most famously, the V-1 flying bomb and V-2 rocket.[1][36] In one Project Big Ben mission (Operation Wildhorn III;[39] Polish cryptonym, Most III, "Bridge III"), a stripped-for-lightness RAF twin-engine Dakota flew from Brindisi, Italy, to an abandoned German airfield in Poland to pick up intelligence prepared by Polish aircraft-designer Antoni Kocjan, including 100 lb (45 kg) of V-2 rocket wreckage from a Peenemünde launch, a Special Report 1/R, no. 242, photographs, eight key V-2 parts, and drawings of the wreckage.[40] Polish agents also provided reports on the German war production, morale, and troop movements.[32] The Polish intelligence network extended beyond Poland and even beyond Europe: for example, the intelligence network organized by Mieczysław Zygfryd Słowikowski in North Africa has been described as "the only [A]llied ... network in North Africa".[32] The Polish network even had two agents in the German high command itself.[32]

The researchers who produced the first Polish–British in-depth monograph on Home Army intelligence (Intelligence Co-operation Between Poland and Great Britain During World War II: Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee, 2005) described contributions of Polish intelligence to the Allied victory as "disproportionally large"[41] and argued that "the work performed by Home Army intelligence undoubtedly supported the Allied armed effort much more effectively than subversive and guerilla activities".[42]

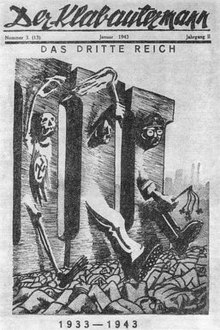

Subversion and propaganda

The Home Army also conducted psychological warfare. Its Operation N created the illusion of a German movement opposing Adolf Hitler within Germany itself.[1]

The Home Army published a weekly Biuletyn Informacyjny (Information Bulletin), with a top circulation (on 25 November 1943) of 50,000 copies.[43][44]

Major operations

Sabotage was coordinated by the Union of Retaliation and later by Wachlarz and Kedyw units.[2]

Major Home Army military and sabotage operations included:

- the Zamość Rising of 1942–1943, with the Home Army sabotaging German plans to expel Poles under Generalplan Ost[2]

- the protection of the Polish population from the massacres of Poles in Volhynia in 1943–1944[2]

- Operation Garland, in 1942, sabotaging German rail transport[2]

- Operation Belt in 1943, a series of attacks on German border outposts on the frontier between the General Government and the territories annexed by Germany

- Operation Jula, in 1944, another rail-sabotage operation[2]

- most notably Operation Tempest; in 1944, a series of nationwide risings which aimed primarily to seize control of cities and areas where German forces were preparing defenses against the Soviet Red Army, so that Polish underground civil authorities could take power before the arrival of Soviet forces.[45]

The largest and best-known of the Operation Tempest battles, the Warsaw Uprising, constituted an attempt to liberate Poland's capital and began on 1 August 1944. Polish forces took control of substantial parts of the city and resisted the German-led forces until 2 October (a total of 63 days). With the Poles receiving no aid from the approaching Red Army, the Germans eventually defeated the insurrectionists and burned the city, quelling the Uprising on 2 October 1944.[1] Other major Home Army city risings included Operation Ostra Brama in Wilno and the Lwów Uprising. The Home Army also prepared for a rising in Kraków but aborted due to various circumstances. While the Home Army managed to liberate a number of places from German control—for example, the Lublin area, where regional structures were able to set up a functioning government—they ultimately failed to secure sufficient territory to enable the government-in-exile to return to Poland due to Soviet hostility.[1][2][45]

The Home Army also sabotaged German rail- and road-transports to the Eastern Front in the Soviet Union.[46] Richard J. Crampton estimated that an eighth of all German transports to the Eastern Front were destroyed or substantially delayed due to Home Army operations.[46]

| Sabotage / covert-operation type | Total numbers |

|---|---|

| Damaged locomotives | 6,930 |

| Damaged railway wagons | 19,058 |

| Delayed repairs to locomotives | 803 |

| Derailed transports | 732 |

| Transports set on fire | 443 |

| Blown-up railway bridges | 38 |

| Disruptions to electricity supply in the Warsaw grid | 638 |

| Damaged or destroyed army vehicles | 4,326 |

| Damaged aeroplanes | 28 |

| Destroyed fuel-tanks | 1,167 |

| Destroyed fuel (in tonnes) | 4,674 |

| Blocked oil wells | 5 |

| Destroyed wood wool wagons | 150 |

| Burned down military stores | 130 |

| Disruptions in factory production | 7 |

| Built-in flaws in aircraft engines parts | 4,710 |

| Built-in flaws in cannon muzzles | 203 |

| Built-in flaws in artillery projectiles | 92,000 |

| Built-in flaws in air-traffic radio stations | 107 |

| Built-in flaws in condensers | 70,000 |

| Built-in flaws in electro-industrial lathes | 1,700 |

| Damage to important factory machinery | 2,872 |

| Acts of sabotage | 25,145 |

| Assassinations of Nazi Germans | 5,733 |

Assassination of Nazi leaders

The Polish Resistance carried out dozens of attacks on German commanders in Poland, the largest series being that codenamed "Operation Heads". Dozens of additional assassinations were carried out, the best-known being:

- Operation Bürkl—Franz Bürkl, SS-Oberscharführer, Gestapo officer, and commandant of the Pawiak prison, assassinated 7 September 1943.[49]

- Operation Kutschera—Franz Kutschera, SS-Brigadeführer and Generalmajor of Ordnungspolizei; SS and Police Leader of the Warsaw District, assassinated 1 February 1944.[50]

Weapons and equipment

As a clandestine army operating in an enemy-occupied country and separated by over a thousand kilometers from any friendly territory, the Home Army faced unique challenges in acquiring arms and equipment,[51] though it was able to overcome these difficulties to some extent and to field tens of thousands of armed soldiers. Nevertheless, the difficult conditions meant that only infantry forces armed with light weapons could be fielded. Any use of artillery, armor or aircraft was impossible (except for a few instances during the Warsaw Uprising, such as the Kubuś armored car).[51][52] Even these light-infantry units were as a rule armed with a mixture of weapons of various types, usually in quantities sufficient to arm only a fraction of a unit's soldiers.[13][8]: 234 [51]

Home Army arms and equipment came mostly from four sources: arms that had been buried by the Polish armies on battlefields after the 1939 invasion of Poland, arms purchased or captured from the Germans and their allies, arms clandestinely manufactured by the Home Army itself, and arms received from Allied air drops.[51]

From arms caches hidden in 1939, the Home Army obtained 614 heavy machine guns, 1,193 light machine guns, 33,052 rifles, 6,732 pistols, 28 antitank light field guns, 25 antitank rifles, and 43,154 hand grenades. However, due to their inadequate preservation, which had to be improvised in the chaos of the September Campaign, most of the guns were in poor condition. Of those that had been buried in the ground and had been dug up in 1944 during preparations for Operation Tempest, only 30% were usable.[53]: 63

Arms were sometimes purchased on the black market from German soldiers or their allies, or stolen from German supply depots or transports.[51] Efforts to capture weapons from the Germans also proved highly successful. Raids were conducted on trains carrying equipment to the front, as well as on guardhouses and gendarmerie posts. Sometimes weapons were taken from individual German soldiers accosted in the street. During the Warsaw Uprising, the Home Army even managed to capture several German armored vehicles, most notably a Jagdpanzer 38 Hetzer light tank destroyer renamed Chwat and an armored troop transport SdKfz 251 renamed Grey Wolf.[52]

Arms were clandestinely manufactured by the Home Army in its own secret workshops, and by Home Army members working in German armaments factories.[51] In this way the Home Army was able to procure submachine guns (copies of British Stens, indigenous Błyskawicas and KIS), pistols (Vis), flamethrowers, explosive devices, road mines, and Filipinka and Sidolówka hand grenades.[51] Hundreds of people were involved in the manufacturing effort. The Home Army did not produce its own ammunition, but relied on supplies stolen by Polish workers from German-run factories.[51]

The final source of supply was Allied air drops, which was the only way to obtain more exotic, highly useful equipment such as plastic explosives and antitank weapons such as the British PIAT. During the war, 485 air-drop missions from the West (about half of them flown by Polish airmen) delivered some 600 tons of supplies for the Polish resistance.[54] Besides equipment, the planes also parachuted in highly qualified instructors (Cichociemni), 316 of whom were inserted into Poland during the war.[10][55]

Air drops were infrequent. Deliveries from the west were limited by Stalin's refusal to let the planes land on Soviet territory, the low priority placed by the British on flights to Poland; and the extremely heavy losses sustained by Polish Special Duties Flight personnel. Britain and the United States attached more importance to not antagonizing Stalin than they did to the aspirations of the Poles to regain their national sovereignty, particularly after Hitler attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941 and the Soviets joined the Western Allies in the war against Germany.[56]

In the end, despite all efforts, most Home Army forces had inadequate weaponry. In 1944, when the Home Army was at its peak strength (200,000–600,000, according to various estimates), the Home Army had enough weaponry for only about 32,000 soldiers."[8]: 234 On 1 August 1944, when the Warsaw Uprising began, only a sixth of Home Army fighters in Warsaw were armed.[8]: 234

Relations with ethnic groups

Jews

Home Army members' attitudes toward Jews varied widely from unit to unit,[57][58][59] and the topic remains controversial.[60] The Home Army answered to the National Council of the Polish government-in-exile, where some Jews served in leadership positions (e.g. Ignacy Schwarzbart and Szmul Zygielbojm),[61] though there were no Jewish representatives in the Government Delegation for Poland.[62]: 110–114 Traditionally, Polish historiography has presented the Home Army interactions with Jews in a positive light, while Jewish historiography has been mostly negative; most Jewish authors attribute the Home Army's hostility to endemic antisemitism in Poland.[63] More recent scholarship has presented a mixed, ambivalent view of Home Army–Jewish relations. Both "profoundly disturbing acts of violence as well as extraordinary acts of aid and compassion" have been reported. In an analysis by Joshua D. Zimmerman, postwar testimonies of Holocaust survivors reveal that their experiences with the Home Army were mixed even if predominantly negative.[64] Jews trying to seek refuge from Nazi genocidal policies were often exposed to greater danger by open resistance to German occupation.[65]: 273

Members of the Home Army were named Righteous Among the Nations for risking their lives to save Jews, examples include Jan Karski,[66] Aleksander Kamiński,[67] Stefan Korboński,[68] Henryk Woliński,[69] Jan Żabiński,[70] Władysław Bartoszewski,[71] Mieczysław Fogg,[72] Henryk Iwański,[73] and Jan Dobraczyński.[74]

Daily operations

A Jewish partisan detachment served in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising,[75][76] and another in Hanaczów.[77][78] The Home Army provided training and supplies to the Warsaw Ghetto's Jewish Combat Organization.[77] It is likely that more Jews fought in the Warsaw Uprising than in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, some fought in both.[65]: 273 Thousands of Jews joined, or claimed to join, the Home Army in order to survive in hiding, but Jews serving in the Home Army were the exception rather than the rule. Most Jews in hiding could not pass as ethnic Poles and would have faced deadly consequences if discovered.[79][65]: 275

In February 1942, the Home Army Operational Command's Office of Information and Propaganda set up a Section for Jewish Affairs, directed by Henryk Woliński.[80] This section collected data about the situation of the Jewish population, drafted reports, and sent information to London. It also centralized contacts between Polish and Jewish military organizations. The Home Army also supported the Relief Council for Jews in Poland (Żegota) as well as the formation of Jewish resistance organizations.[81][82]

Holocaust

From 1940 onward, the Home Army courier Jan Karski delivered the first eyewitness account of the Holocaust to the Western powers, after having personally visited the Warsaw Ghetto and a Nazi concentration camp.[62]: 110–114 [83][38][37] Another crucial role was played by Witold Pilecki, who was the only person to volunteer to be imprisoned at Auschwitz (where he would spend three and a half years) to organize a resistance on the inside and to gather information on the atrocities occurring there to inform the Western Allies about the fate of the Jewish population.[84] Home Army reports from March 1943 described crimes committed by the Germans against the Jewish populace. AK commander General Stefan Rowecki estimated that 640,000 people had been murdered in Auschwitz between 1940 and March 1943, including 66,000 ethnic Poles and 540,000 Jews from various countries (this figure was revised later to 500,000).[85] The Home Army started carrying out death sentences for szmalcowniks in Warsaw in the summer of 1943.[86]

Antony Polonsky observed that "the attitude of the military underground to the genocide is both more complex and more controversial [than its approach towards szmalcowniks]. Throughout the period when it was being carried out, the Home Army was preoccupied with preparing for ... [the moment when] Nazi rule in Poland collapsed. It was determined to avoid premature military action and to conserve its strength (and weapons) for the crucial confrontation that, it was assumed, would determine the fate of Poland. ... [However,] to the Home Army, the Jews were not a part of 'our nation' and ... action to defend them was not to be taken if it endangered [the Home Army's] other objectives." He added that "it is probably unrealistic to have expected the Home Army—which was neither as well armed nor as well organized as its propaganda claimed—to have been able to do much to aid the Jews. The fact remains that its leadership did not want to do so."[87]: 68 Rowecki's attitudes shifted in the following months as the brutal reality of the Holocaust became more apparent, and the Polish public support for the Jewish resistance increased. Rowecki was willing to provide Jewish fighters with aid and resources when it contributed to "the greater war effort", but had concluded that providing large quantities of supplies to the Jewish resistance would be futile. This reasoning was the norm among the Allies, who believed that the Holocaust could only be halted by a significant military action.[62]: 110–122

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

The Home Army provided the Warsaw Ghetto with firearms, ammunition, and explosives,[88] but only after it was convinced of the eagerness of the Jewish Combat Organization (Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa, ŻOB) to fight,[87]: 67 and after Władysław Sikorski's intervention on the Organization's behalf.[89] Zimmerman describes the supplies as "limited but real".[62]: 121-122 Jewish fighters of the Jewish Military Union (Żydowski Związek Wojskowy, ŻZW) received from the Home Army, among other things, 2 heavy machine guns, 4 light machine guns, 21 submachine guns, 30 rifles, 50 pistols, and over 400 grenades.[90] Some supplies were also provided to the ŻOB, but less than to ŻZW with whom the Home Army had closer ties and ideological similarities.[91] Antoni Chruściel, commander of the Home Army in Warsaw, ordered the entire armory of the Wola district transferred to the ghetto.[92] In January 1943 the Home Army delivered a larger shipment of 50 pistols, 50 hand grenades, and several kilograms of explosives, along with a number of smaller shipments that carried a total of 70 pistols, 10 rifles, 2 hand machine guns, 1 light machine gun, ammunition, and over 150 kilograms of explosives.[92][93] The number of supplies provided to the ghetto resistance has been sometimes described as insufficient, as the Home Army faced a number of dilemmas which forced it to provide no more than limited assistance to the Jewish resistance, such as supply shortages and the inability to arm its own troops, the view (shared by most of the Jewish resistance) that any wide-scale uprising in 1943 would be premature and futile, and the difficulty of coordinating with the internally divided Jewish resistance, coupled with the pro-Soviet attitude of the ŻOB.[94][92] During the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Home Army units tried to blow up the Ghetto wall twice, carried out diversionary actions outside the Ghetto walls, and attacked German sentries sporadically near the Ghetto walls.[95][96] According to Marian Fuks, the Ghetto uprising would not have been possible without supplies from the Polish Home Army.[97][92]

A year later, during the 1944 Warsaw Uprising, the Zośka Battalion liberated hundreds of Jewish inmates from the Gęsiówka section of the Warsaw concentration camp.[65]: 275

Attitude to fugitives

Because it was the largest Polish resistance organization, the Home Army's attitude towards Jewish fugitives often determined their fate.[63] According to Antony Polonsky the Home Army saw Jewish fugitives as security risks.[87]: 66 At the same time, AK's "paper mills" supplied forged identification documents to many Jewish fugitives, enabling them to pass as Poles.[65]: 275 Home Army published a leaflet in 1943 stating that "Every Pole is obligated to help those in hiding. Those who refuse them aid will be punished on the basis of...treason to the Polish Nation".[98] Nevertheless, Jewish historians have asserted that the main cause for the low survival rates of escaping Jews was the antisemitism of the Polish population.[99]

Attitudes towards Jews in the Home Army were mixed.[59] A few AK units actively hunted down Jews,[100]: 238 [101] and in particular two district commanders in the northeast of Poland (Władysław Liniarski of Białystok and Janusz Szlaski of Nowogródek) openly and routinely persecuted Jewish partisans and fugitives;[102] however, these were the only two provinces, out of seventeen, where such orders were issued by provincial commanders.[103] The extent of such behaviors in the Home Army overall has been disputed;[104]: 88–90 [105] Tadeusz Piotrowski wrote that the bulk of the Home Army's antisemitic behavior can be ascribed to a small minority of members,[104]: 88–90 often affiliated with the far-right National Democracy (ND, or Endecja) party, whose National Armed Forces organization was mostly integrated into the Home Army in 1944.[106]: 17 [106]: 45 Adam Puławski has suggested that some of these incidents are better understood in the context of the Polish–Soviet conflict, as some of the Soviet-affiliated partisan units that AK units attacked or was attacked by had a sizable Jewish presence.[77] In general, AK units in the east were more likely to be hostile towards Jewish partisans, who in turn were more closely associated with the Soviet underground, while AK units in the west were more helpful towards the Jews. The Home Army had a more favorable attitude towards Jewish civilians and was more hesitant or hostile towards independent Jewish partisans, whom it suspected of pro-Soviet sympathies.[107] General Rowecki believed that antisemitic attitudes in eastern Poland were related to Jewish involvement with Soviet partisans.[108] Some AK units were friendly to Jews,[109] and in Hanaczów Home Army officers hid and protected an entire 250-person Jewish community, and supplied a Jewish Home Army platoon.[110] The Home Army leadership punished a number of perpetrators of antisemitic violence in its ranks, in some cases sentencing them to death.[104]: 88–90

Most of the underground press was sympathetic towards Jews,[85] and the Home Army's Bureau of Information and Propaganda was led by operatives who were pro-Jewish and represented the liberal wing of Home Army;[85] however, the bureau's anti-communist sub-division, created as a response to communist propaganda, was led by operatives who held strong anti-communist and anti-Jewish views, including the Żydokomuna stereotype.[111][85] The perceived association between Jews and communists was actively reinforced by Operation Antyk, whose initial reports "tended to conflate communists with Jews, dangerously disseminating the notion that Jewish loyalties were to Soviet Russia and communism rather than to Poland", and which repeated the notion that antisemitism was a "useful tool in the struggle against Soviet Russia".[112]

Lithuanians

Although the Lithuanian and Polish resistance movements had common enemies—Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union—they began working together only in 1944–1945, after the Soviet reoccupation, when both fought the Soviet occupiers.[113] The main obstacle to unity was a long-standing territorial dispute over the Vilnius Region.[114]

The Lithuanian Activist Front (Lietuvos Aktyvistų Frontas, or LAF)[104]: 163 cooperated with Nazi operations against Poles during the German occupation. In autumn 1943, the Home Army carried retaliatory out operations against the Nazis' Lithuanian supporters, mainly the Lithuanian Schutzmannschaft battalions, the Lithuanian Territorial Defense Force, and the Lithuanian Secret Police,[115] killing hundreds of mostly Lithuanian policemen and other collaborators during the first half of 1944. In response, the Lithuanian Sonderkommando, who had already killed hundreds of Polish civilians since 1941 (particularly the Ponary massacre),[104]: 168–169 intensified their operations against the Poles.

In April 1944, the Home Army in the Vilnius Region attempted to open negotiations with Povilas Plechavičius, commander of the Lithuanian Territorial Defense Force, and proposed a non-aggression pact and cooperation against Nazi Germany.[116] The Lithuanian side refused and demanded that the Poles either leave the Vilnius region (disputed between Poles and Lithuanians) or subordinate themselves to the Lithuanians' struggle against the Soviets.[116] In the May 1944 Battle of Murowana Oszmianka, the Home Army dealt a substantial blow to the Nazi-sponsored Lithuanian Territorial Defense Force,[104]: 165–166 [117] which resulted in a low-level civil war between anti-Nazi Poles and pro-Nazi Lithuanians that was encouraged by the German authorities;[115] it culminated in the June 1944 massacres of Polish and Lithuanian civilians in the villages of Glitiškės (Glinciszki) and Dubingiai (Dubinki) respectively.[104]: 168–169

Postwar assessments of the Home Army's activities in Lithuania have been controversial. In 1993, the Home Army's activities there were investigated by a special Lithuanian government commission. Only in recent years have Polish and Lithuanian historians been able to approach consensus, though still differing in their interpretations of many events.[118][119]

Ukrainians

In the Southeastern part of occupied Polish territories, there have been long-standing tensions between the Polish and Ukrainian populations. Poland's plans to restore its prewar borders were opposed by the Ukrainians, and some Ukrainian groups' collaboration with Nazi Germany had discredited their partisans as potential Polish allies.[120] While the Polish government-in-exile considered tentative plans about providing a limited autonomy for Ukrainians, in 1942 the staff of the Home Army of Lviv recommended deporting 1–1.5 million Ukrainians to the Soviet Union and settling the remainder in other parts of Poland once the war ended.[121] The situation escalated the next year when the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (Українська повстанська армія, Ukrayins'ka Povstans'ka Armiya, UPA), a Ukrainian nationalist force and the military arm of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (Організація Українських Націоналістів, Orhanizatsiya Ukrayins'kykh Natsionalistiv, OUN),[122] directed most of its attacks against Poles and Jews.[123] Stepan Bandera, one of UPA's leaders, and his followers concluded that the war would end in the exhaustion of both Germany and the Soviet Union, leaving only the Poles—who laid claim to East Galicia (viewed by the Ukrainians as western Ukraine, and by the Poles as Kresy)—as a significant force, and therefore the Poles had to be weakened before the war's end.[120]

The OUN decided to attack Polish civilians, who constituted about a third of the population of the disputed territories.[120] It equated Ukrainian independence with ethnic homogeneity, which meant the Polish presence had to be completely removed.[120] By February 1943 the OUN began a deliberate campaign of killing Polish civilians.[120] In massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia, beginning in the spring of 1943, 100,000 Poles were killed.[124][125][126] OUN forces targeted Polish villages, which prompted the formation of Polish self-defense units (e.g., the Przebraże Defence) and fights between the Home Army and the OUN.[120][127][128] The Germans encouraged both sides against each other; Erich Koch said: "We have to do everything possible so that a Pole, when meeting a Ukrainian, will be ready to kill him, and conversely, a Ukrainian will be ready to kill the Pole." A German commissioner from Sarny, when local Poles complained about massacres, answered: "You want Sikorski, the Ukrainians want Bandera. Fight each other."[129] On 10 July 1943, Zygmunt Rumel was sent to talk with local Ukrainians with the goal of ending the massacres; the mission was unsuccessful, and the Banderites killed the Polish delegation.[130] On 20 July that year the Home Army command decided to establish partisan units in Volhynia. Several formations were created, most notably, in January 1944, the 27th Home Army Infantry Division. Between January and March 1944, the division fought 16 major battles with the UPA, expanding its operational base and securing Polish forces against the main attack.[131] One of the largest battles between the Home Army and the UPA took place in Hanaczów, where local self-defence forces managed to fend off two attacks.[132] In March 1944 the Home Army also carried out reprisal attack against UPA in the village of Sahryń, remembered as "Sahryń massacre", ended in ethnic cleansing operations in which about 700 Ukrainian civilians were killed.[133]

The Polish government-in-exile in London was taken by surprise; it did not expect Ukrainian anti-Polish actions of such magnitude.[120] There is no evidence that the Polish government-in-exile contemplated a general policy of revenge against the Ukrainians, but local Poles, including Home Army commanders, engaged in retaliatory actions.[120] Polish partisans attacked the OUN, assassinated Ukrainian commanders, and carried out operations against Ukrainian villages.[120] Retaliatory operations aimed at intimidating the Ukrainian population contributed to increased support for the UPA.[134] The Home Army command tried to limit operations against Ukrainian civilians to a minimum.[135] According to Grzegorz Motyka, the Polish operations resulted in 10,000 to 15,000 Ukrainian deaths in 1943–47,[136] including 8,000-10,000 on territory of post-war Poland.[137][138] From February to April 1945, mainly in Rzeszowszczyzna (the Rzeszów area), Polish units (including affiliates of the Home Army) carried out retaliatory attacks in which about 3,000 Ukrainians were killed; one of the most infamous ones is known as the Pawłokoma massacre.[139][140]

By mid-1944, most of the disputed regions were occupied by the Soviet Red Army. Polish partisans disbanded or went underground, as did most Ukrainian partisans. Both the Poles and the Ukrainians would increasingly concentrate on the Soviets as their primary enemy – and both would ultimately fail.[120]

Relations with the Soviet Union

Home Army relations with the Soviet Red Army grew worse as the war progressed. The Soviet Union invaded Poland on 17 September 1939 after the German invasion that began on 1 September 1939; even though the Germans invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Soviets saw Polish partisans loyal to the Polish government-in-exile more as a potential obstacle to Soviet plans to control postwar Poland than as a potential ally.[141] On orders from the Soviet Stavka (high command) issued on 22 June 1943,[104]: 98–99 Soviet partisans engaged Polish partisans in combat; it has also been claimed that they attacked the Poles more frequently than the Germans.[141]

In late 1943 the actions of Soviet partisans, who had been ordered to destroy Home Army forces,[104]: 98–99 even resulted in limited uneasy cooperation between some Home Army units and German forces.[104]: 88–90 While the Home Army still treated the Germans as the enemy and conducted operations against them,[104]: 88–90 some Polish units in the Nowogródek and Wilno areas accepted them when the Germans offered arms and supplies to the Home Army to be used against the Soviet partisans. However, such arrangements were purely tactical and indicated no ideological collaboration, as demonstrated by France's Vichy regime or Norway's Quisling regime.[104]: 88–90 The Poles' main motive was to acquire intelligence on the Germans and to obtain much-needed equipment.[57] There were no known joint Polish–German operations, and the Germans were unsuccessful in recruiting the Poles to fight exclusively against the Soviet partisans.[104]: 88–90 Furthermore, most cooperative efforts between local Home Army commanders and the Germans were condemned by Home Army headquarters.[104]: 88–90

With the Eastern Front entering Polish territories in 1944, the Home Army established an uneasy truce with the Soviets. Even so, the main Red Army and NKVD forces conducted operations against Home Army partisans, including during or directly after Poland's Operation Tempest, which the Poles had envisioned to be a joint Polish–Soviet operation against the retreating Germans which would also establish Polish claims to those territories.[142][better source needed] The Home Army helped Soviet units with scouting assistance, uprisings, and assistance in liberating some cities (e.g., Operation Ostra Brama in Vilnius, and the Lwów Uprising), only to find that Home Army troops were arrested, imprisoned, or executed immediately afterwards.[46]

Long after the war, Soviet forces continued engaging many Home Army soldiers, who received the moniker of "cursed soldiers".[142][better source needed]

Postwar

The Home Army was officially disbanded on 19 January 1945 to avoid civil war and armed conflict with the Soviets. However, many former Home Army units decided to continue operations. The Soviet Union, and the Polish communist government that it controlled, viewed the underground, still loyal to the Polish government-in-exile, as a force to be extirpated before they could gain complete control of Poland. Future Secretary General of the Polish United Workers' Party, Władysław Gomułka, is quoted as saying: "Soldiers of the AK are a hostile element which must be removed without mercy." Another prominent Polish communist, Roman Zambrowski, said that the Home Army had to be "exterminated."[142][better source needed]

The first Home Army structure designed primarily to deal with the Soviet threat had been NIE, formed in mid-1943. Its aim was not to engage Soviet forces in combat, but to observe them and to gather intelligence while the Polish Government-in-Exile decided how to deal with the Soviets; at that time, the exiled government still believed in the possibility of constructive negotiations with the Soviets. On 7 May 1945 NIE was disbanded and transformed into the Armed Forces Delegation for Poland (Delegatura Sił Zbrojnych na Kraj), but it was disbanded on 8 August 1945 to stop partisan resistance.[142][better source needed]

The first Polish communist government formed in July 1944—the Polish Committee of National Liberation—declined to accept jurisdiction over Home Army soldiers; as a result, for over a year Soviet agencies such as the NKVD took responsibility for disarming the Home Army. By the end of the war, around 60,000 Home Army soldiers were arrested, 50,000 of whom were deported to Soviet gulags and prisons; most of these soldiers had been taken captive by the Soviets during or after Operation Tempest when many Home Army units tried to work together with the Soviets in a nationwide uprising against the Germans. Other Home Army veterans were arrested when they approached Polish communist government officials after having been promised amnesty. Home Army soldiers stopped trusting the government after a number of broken promises in the first few years of communist control.[142][better source needed]

The third post-Home Army organization was Freedom and Independence (Wolność i Niezawisłość, WiN). Its primary goal was not fighting; rather, it was designed to help Home Army soldiers transition from partisan to civilian life; while secrecy was necessary in light of increasing persecution of Home Army veterans by the communist government.[143][better source needed] WiN was in great need of funds to pay for false documents and provide resources for the partisans, many of whom had lost their homes and life savings in the war. WiN was far from efficient: it was viewed as an enemy of the state, starved of resources, and a vocal faction advocated armed resistance against the Soviets and their Polish proxies. In the second half of 1945, the Soviet NKVD and the newly created Polish secret police, the Department of Security (Urząd Bezpieczeństwa, UB), managed to convince several Home Army and WiN leaders that they wanted to offer amnesty to Home Army members, and gained information about large numbers of Home Army and WiN people and resources in the following months. By the time the (imprisoned) Home Army and WiN leaders realised their mistake, the organizations had been crippled, with thousands of their members arrested. WiN was finally disbanded in 1952. By 1947 a colonel of the communist forces declared that "The terrorist and political underground [had] ceased to be a threatening force, though there [were] still men of the forests" to be dealt with.[142][better source needed]

The persecution of the Home Army was only part of the Stalinist repressions in Poland. In 1944–56, approximately 2 million people were arrested; over 20,000, including Pilecki, organizer of the resistance in Auschwitz, were executed in communist prisons, and 6 million Polish citizens (every third adult Pole) were classified as "reactionary" or "criminal elements", and were subjected to spying by state agencies.[142][better source needed]

Most Home Army soldiers were captured by the NKVD or by Poland's UB political police. They were interrogated and imprisoned on various charges such as "fascism".[144][145] Many were sent to Gulags, executed, or "disappeared".[144] For example, all the members of Batalion Zośka, which had fought in the Warsaw Uprising, were locked up in communist prisons between 1944 and 1956.[146] In 1956 an amnesty released 35,000 former Home Army soldiers from prisons.[147]

Even then, some partisans remained in the countryside, and were unwilling or unable to rejoin the community; they became known as the cursed soldiers. Stanisław Marchewka "Ryba" was killed in 1957, and the last AK partisan, Józef "Lalek" Franczak, was killed in 1963 – almost two decades after World War II had ended. It was only four years later, in 1967, that Adam Boryczka—a soldier of AK and a member of the elite, Britain-trained Cichociemny ("Silent Unseen") intelligence and support group—was released from prison. Until the end of the People's Republic of Poland, Home Army soldiers remained under investigation by the secret police, and it was only in 1989, after the fall of communism, that the sentences of Home Army soldiers were finally declared null and void by Polish courts.[142][better source needed]

Many monuments to the Home Army have since been erected in Poland, including the Polish Underground State and Home Army Monument near the Sejm building in Warsaw, unveiled in 1999.[148][149] The Home Army is also commemorated in the Home Army Museum in Kraków[150] and in the Warsaw Uprising Museum in Warsaw.[151]

See also

- Gray Ranks

- Polish contribution to World War II

- Polish resistance movement in World War II

- Western betrayal

Notes

- ^ a b A number of sources say that the Home Army was the largest resistance movement in Nazi-occupied Europe. Norman Davies writes that "Armia Krajowa (Home Army), the AK, ... could fairly claim to be the largest of European resistance [organizations]."[152] Gregor Dallas writes that the "Home Army (Armia Krajowa or AK) in late 1943 numbered around 400,000, making it the largest resistance organization in Europe."[153] Mark Wyman writes that "Armia Krajowa was considered the largest underground resistance unit in wartime Europe."[154] The numbers of Soviet partisans were very similar to those of the Polish resistance.[155][156]

References

- Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Marek Ney-Krwawicz, The Polish Underground State and The Home Army (1939–45) Archived 3 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Translated from Polish by Antoni Bohdanowicz. Article on the pages of the London Branch of the Polish Home Army Ex-Servicemen Association. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Armia Krajowa". Encyklopedia PWN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

- ^ a b Tomasz Strzembosz, Początki ruchy oporu w Polsce. Kilka uwag. In Krzysztof Komorowski (ed.), Rozwój organizacyjny Armii Krajowej, Bellona, 1996, ISBN 83-11-08544-7

- ^ a b Prazmowska, A. (29 July 2004). Civil War in Poland 1942-1948. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-230-50488-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r (in Polish) Armia Krajowa Archived 14 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Encyklopedia WIEM. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- ^ Wróbel, Piotr (27 January 2014). Historical Dictionary of Poland 1945-1996. Taylor & Francis. p. 1872. ISBN 978-1-135-92701-1.

- ^ Rozett, Robert; Spector, Shmuel (26 November 2013). Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. Routledge. pp. 506–. ISBN 978-1-135-96957-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Roy Francis Leslie (19 May 1983). The History of Poland Since 1863. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27501-9.

- ^ Andrew A. Michta (1990). Red Eagle: The Army in Polish Politics, 1944–1988. Hoover Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-8179-8861-6.

- ^ a b c d Polish contribution to the Allied victory in World War 2 (1939–1945). Publications of Embassy of the Republic of Poland in Canada. Retrieved 21 December 2006.

- ^ a b Laqueur, Walter (2019). "5. The Twentieth Century (II): Partisans against Hitler". Guerrilla: A Historical and Critical Study. Milton: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-69636-7. OCLC 1090493874.

- ^ Stanisław Salmonowicz, Polskie Państwo Podziemne, Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, Warszawa, 1994, ISBN 83-02-05500-X, p.317

- ^ a b Guerrilla Warfare: A Historical and Critical Study. Transaction Publishers. pp. 202–203. ISBN 978-1-4128-2488-0.

- ^ Wojskowy przegla̜d historyczny (in Polish). s.n. 1996. p. 134.

- ^ Hanna Konopka; Adrian Konopka (1 January 1999). Leksykon historii Polski po II wojnie światowej 1944–1997 (in Polish). Graf-Punkt. p. 130. ISBN 978-83-87988-08-1.

- ^ "Armia Ludowa". Encyklopedia PWN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2006.

- ^ autor zbiorowy (23 November 2015). Wielka Księga Armii Krajowej. Otwarte. p. 294. ISBN 978-83-240-3431-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Drapikowska, Barbara (2013). "Militarna partycypacja kobiet w Siłach Zbrojnych RP". Zeszyty Naukowe AON. 2 (91): 166–194. Archived from the original on 9 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Women and War: A Historical Encyclopedia from Antiquity to the Present. ABC-CLIO. 2006. p. 472. ISBN 978-1-85109-770-8.

- ^ a b Drapikowska, Barbara (2016). "Kobiety w polskiej armii – ujęcie historyczne". Czasopismo Naukowe Instytutu Studiów Kobiecych (in Polish) (1): 45–65. doi:10.15290/cnisk.2016.01.01.03. ISSN 2451-3539. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023.

- ^ Półturzycki, Józef (2014). "Spór o Elżbietę Zawacką – żołnierza i pedagoga". Rocznik Andragogiczny (in Polish). 21: 317–332. doi:10.12775/RA.2014.023. ISSN 2391-7571. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023.

- ^ "Grażyna Lipińska – życiorys" (PDF). Załącznik do Uchwały Senatu PW nr 202/XLVI/2007 z dnia 27 June 2007 r. (in Polish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 May 2023.

- ^ Jerzy Turonek (1992). Wacław Iwanowski i odrodzenie Białorusi (in Polish). Warszawska Oficyna Wydawnicza "Gryf". p. 118. ISBN 978-83-85209-12-6.

- ^ Marcinkiewicz-Kaczmarczyk, Anna (18 November 2015). "Żeńskie oddziały sabotażowo-dywersyjne w strukturach armii podziemnej w latach 1940–1944 na podstawie relacji i wspomnień ich członkiń". Pamięć I Sprawiedliwość. 2 (26): 115–138 – via cejsh.icm.edu.pl.

- ^ Tendyra, Bernadeta (26 July 2004). "The Warsaw women who took on Hitler". Archived from the original on 12 January 2022 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ Malgorzata Fidelis (21 June 2010). Women, Communism, and Industrialization in Postwar Poland. Cambridge University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-521-19687-1.

- ^ Marek Ney-Krwawicz (1993). Armia Krajowa: siła zbrojna Polskiego Państwa Polskiego (in Polish). Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne. pp. 18–25. ISBN 978-83-02-05061-9.

- ^ LERSKI, GEORGE J. (1982). "Review of GENERAŁ: Opowieść o Leopoldzie Okulickim (The General: Story of Leopold Okulicki), Jerzy R. Krzyżanowski". The Polish Review. 27 (1/2): 166–168. ISSN 0032-2970. JSTOR 25777876.

- ^ Nowak-Jeziorański, Jan (2003). "Gestapo i NKWD". Karta (in Polish) (37): 88–97. ISSN 0867-3764.

- ^ Jerzy Jan Lerski; George J. Lerski; Halina T. Lerski (1996). Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 47, 401, 513–514, 605–505. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0.

- ^ Wiesław Józef Wiąk (2003). Struktura organizacyjna Armii Krajowej 1939-1944 (in Polish). UPJW. pp. 5, 82. ISBN 978-83-916862-7-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Kochanski, Halik (13 November 2012). The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War. Harvard University Press. pp. 234–236. ISBN 978-0-674-06816-2.

- ^ Soybel, Phyllis L. (2007). "Intelligence Cooperation between Poland and Great Britain during World War II. The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee". Sarmatian Review. XXVII (1): 1266–1267. ISSN 1059-5872.

- ^ Schwonek, Matthew R. (19 April 2006). "Intelligence Co-operation Between Poland and Great Britain during World War II: The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee, vol. 1 (review)". The Journal of Military History. 70 (2): 528–529. doi:10.1353/jmh.2006.0128. ISSN 1543-7795. S2CID 161747036.

- ^ Peszke, Michael Alfred (1 December 2006). "A Review of: "Intelligence Co-Operation between Poland and Great Britain during World War II — The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee"". The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 19 (4): 787–790. doi:10.1080/13518040601028578. ISSN 1351-8046. S2CID 219626554.

- ^ a b Ney-Krwawicz (2001), p. 98.

- ^ a b Zimmerman (2015), p. 54.

- ^ a b Engel, David (1983). "An Early Account of Polish Jewry under Nazi and Soviet Occupation Presented to the Polish Government-In-Exile, February 1940". Jewish Social Studies. 45 (1): 1–16. ISSN 0021-6704. JSTOR 4467201.

- ^ Ordway, Frederick I., III. "The Rocket Team." Apogee Books Space Series 36 (pgs 158, 173)

- ^ McGovern, James. "Crossbow and Overcast." W. Morrow: New York, 1964. (pg 71)

- ^ Anglo-Polish Historical Committee (2005). Tessa Stirling; Daria Nałęcz; Tadeusz Dubicki (eds.). Intelligence Co-operation Between Poland and Great Britain During World War II: Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee. Vallentine Mitchell. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-85303-656-2.

This tendency influenced the unwillingness to recognize the disproportionally large contribution of Polish Intelligence to the Allied victory over Germany

- ^ Anglo-Polish Historical Committee (2005). Tessa Stirling; Daria Nałęcz; Tadeusz Dubicki (eds.). Intelligence Co-operation Between Poland and Great Britain During World War II: Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee. Vallentine Mitchell. p. 410. ISBN 978-0-85303-656-2.

- ^ "Biuletyn Informacyjny : wydanie codzienne". dLibra Digital Library. Warsaw Public Library. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ ""Biuletyn Informacyjny" wychodził w konspiracji co tydzień przez pięć lat. Rekordowy nakład - 50 tys. egzemplarzy". wpolityce.pl. 24 November 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Burza". Encyklopedia PWN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

- ^ a b c Crampton, R.J. (1994). Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century. Routledge. pp. 197–198. ISBN 978-0-415-05346-4.

- ^ Ney-Krwawicz (2001), p. 166.

- ^ Marek Ney-Krwawicz (1993). Armia Krajowa: siła zbrojna Polskiego Państwa Polskiego (in Polish). Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne. p. 214. ISBN 978-83-02-05061-9.

- ^ Strzembosz (1983), pp. 343–346.

- ^ Strzembosz (1983), p. 423.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rafal E. Stolarski, The Production of Arms and Explosive Materials by the Polish Home Army in the Years 1939–1945. Archived 30 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine Translated from Polish by Antoni Bohdanowicz. Article on the pages of the London Branch of the Polish Home Army Ex-Servicemen Association. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

- ^ a b Evan McGilvray (19 July 2015). Days of Adversity: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Helion & Company. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-1-912174-34-8.

- ^ Stefan Korboński, The Polish Underground State, Columbia University Press, 1978, ISBN 0-914710-32-X

- ^ Michael Alfred Peszke (2005). The Polish Underground Army, the Western Allies, and the Failure of Strategic Unity in World War II. McFarland. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-7864-2009-4.

- ^ Stefan Bałuk (2009). Silent and Unseen: I was a Polish WWII Special Ops Commando (in Polish). Askon. p. 125. ISBN 978-83-7452-036-2.

- ^ Peszke (2013), passim.

- ^ a b John Radzilowski, Review of Yaffa Eliach's There Once Was a World: A 900-Year Chronicle of the Shtetl of Eishyshok, Journal of Genocide Research, vol. 1, no. 2 (June 1999), City University of New York.

- ^ Robert D. Cherry; Annamaria Orla-Bukowska (1 January 2007). Rethinking Poles and Jews: Troubled Past, Brighter Future. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-7425-4666-0.

- ^ a b Zimmerman (2015), p. 418.

- ^ Blutinger, Jeffrey (Fall 2010). "An Inconvenient Past: Post-Communist Holocaust Memorialization". Shofar. 29 (1): 73–94. doi:10.1353/sho.2010.0093. ISSN 0882-8539. JSTOR 10.5703/shofar.29.1.73. S2CID 144954562.

- ^ Jewish Responses to Persecution: 1938–1940. Rowman & Littlefield. 2011. p. 478. ISBN 978-0-7591-2039-6.

- ^ a b c d Joshua D. Zimmerman (January 2009). Murray Baumgarten; Peter Kenez; Bruce Allan Thompson (eds.). Case of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 978-0-87413-039-3.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Armstrong, John Lowell (1994). "The Polish Underground and the Jews: A Reassessment of Home Army Commander Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski's Order 116 against Banditry". The Slavonic and East European Review. 72 (2): 259–276. ISSN 0037-6795. JSTOR 4211476.

- ^ Zimmerman, Joshua D. (2019). "The Polish Underground Home Army (AK) and the Jews: What Postwar Jewish Testimonies and Wartime Documents Reveal". East European Politics and Societies and Cultures. 34: 194–220. doi:10.1177/0888325419844816. S2CID 204482531.

- ^ a b c d e Snyder, Timothy (8 September 2015). Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning. Crown/Archetype. ISBN 9781101903469.

- ^ "Karski Jan". The Righteous Among The Nations Database. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Kamiński Aleksander". The Righteous Among The Nations Database.

- ^ "Korbonski Stefan". The Righteous Among The Nations Database. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Woliński Henryk". The Righteous Among The Nations Database. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Żabiński Jan & Żabińska Antonina (Erdman)". The Righteous Among The Nations Database. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Bartoszewski Władysław". The Righteous Among The Nations Database. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Fogg Mieczyslaw". The Righteous Among The Nations Database. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Iwański Henryk & Iwańska Wiktoria". The Righteous Among The Nations Database. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Dobraczyński Jan". The Righteous Among The Nations Database. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ Powstanie warszawskie w walce i dyplomacji - page 23 Janusz Kazimierz Zawodny, Andrzej Krzysztof Kunert 2005

- ^ Shmuel Krakowski (January 2003). "The Attitude of the Polish Underground to the Jewish Question during the Second World War". In Joshua D. Zimmerman (ed.). Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath. Rutgers University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8135-3158-8.

- ^ a b c Adam Puławski (2003). "Postrzeganie żydowskich oddziałów partyzanckich przez Armię Krajową i Delegaturę Rządu RP na Kraj" (PDF). Pamięć i Sprawiedliwość [Memory and Justice] (in Polish). 2 (4): 287. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2023.

- ^ Zimmerman (2015), p. 317.

- ^ Zimmerman 2015, p. 5.

- ^ "Henryk Wolinski". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Archived from the original on 9 May 2023.

- ^ John Wolffe; Open University (2004). Religion in History: Conflict, Conversion and Coexistence. Manchester University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-7190-7107-2.

- ^ "Zegota, page 4/34 of the Report" (PDF). Yad Vashem Shoa Resource Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Robert Cherry; Annamaria Orla-Bukowska (7 June 2007). Rethinking Poles and Jews: Troubled Past, Brighter Future. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 119–120. ISBN 978-1-4616-4308-1.

- ^ Ackerman, Elliot (26 July 2019). "The Remarkable Story of the Man Who Volunteered to Enter Auschwitz". Time. Archived from the original on 8 May 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d Zimmerman (2015), p. 188.

- ^ Jarosław Piekałkiewicz (30 November 2019). Joanna Drzewieniecki (ed.). Dance with Death: A Holistic View of Saving Polish Jews during the Holocaust. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 256–257. ISBN 978-0-7618-7167-5.

- ^ a b c David Cesarani; Sarah Kavanaugh, eds. (2004). Holocaust: Responses to the persecution and mass murder of the Jews. Holocaust: critical concepts in historical studies. Vol. 5. London / New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-27509-5. [page needed]

- ^ David Wdowiński (1963). And we are not saved. New York: Philosophical Library. p. 222. ISBN 0-8022-2486-5. Note: Chariton and Lazar were never co-authors of Wdowiński's memoir. Wdowiński is considered the "single author."

- ^ Rashke, Richard (1995) [1983]. Escape from Sobibor (2nd ed.). University of Illinois Press. p. 416. ISBN 978-0252064791.

- ^ Lukas (2012), p. 175.

- ^ David Wdowiński (1963). And we are not saved. New York: Philosophical Library. p. 222. ISBN 0-8022-2486-5. Note: Chariton and Lazar were never co-authors of Wdowiński's memoir. Wdowiński is considered the "single author".

- ^ a b c d Fuks, Marian (1989). "Pomoc Polaków bojownikom getta warszawskiego" [Assistance of Poles in the Warsaw ghetto uprising]. Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego (in Polish). 1 (149): 43–52, 144.

Without assistance of Poles and even their active participation in some actions, without the supply of arms from the Polish underground movement - the outbreak of the uprising in the Warsaw ghetto was impossible.

- ^ Peter Kenez (January 2009). Murray Baumgarten; Peter Kenez; Bruce Allan Thompson (eds.). The Attitude of the Polish Home Army (AK) to the Jewish Question during the Holocaust: the Case of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. University of Delaware Press. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-0-87413-039-3.

- ^ Monika Koszyńska, Paweł Kosiński, Pomoc Armii Krajowej dla powstańców żydowskich w getcie warszawskim (wiosna 1943 r.), 2012, Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. P.6. Quote: W okresie prowadzenia walki bieżącej ZWZ-AK stanowczo unikało starć zbrojnych, które byłyby skazane na niepowodzenie i okupione ofiarami o skali trudnej do przewidzenia. To podstawowe założenie w praktyce uniemożliwiało AK czynne wystąpienie po stronie Żydów planujących demonstracje zbrojne w likwidowanych przez Niemców gettach... Kłopotem była też niemożność wytypowania przez rozbitą wewnętrznie konspirację żydowską przedstawicieli do prowadzenia rozmów z dowództwem AK.... Ograniczony rozmiar akowskiej pomocy związany był ze stałymi niedoborami uzbrojenia własnych oddziałów... oraz z lewicowym (prosowieckim) obliczem ŻOB...

- ^ Monika Koszyńska, Paweł Kosiński, Pomoc Armii Krajowej dla powstańców żydowskich w getcie warszawskim (wiosna 1943 r.), 2012, Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. P.10-18

- ^ Joshua D. Zimmerman (5 June 2015). The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939–1945. Cambridge University Press. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-1-107-01426-8.

- ^ Joshua D. Zimmerman (9 October 2015). "Zimmerman: Podziemie polskie a Żydzi. Solidarność, zdrada i wszystko pomiędzy" [Zimmerman: Polish underground and Jews. Solidarity, betrayal and everything in between]. ResPublica (Interview) (in Polish). Interviewed by Filip Mazurczak.

- ^ Zimmerman (2015), p. 194.

- ^ Wilhelm Heitmeyer; John Hagan (19 December 2005). International Handbook of Violence Research. Springer. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-4020-3980-5.

- ^ Bauer, Yehuda (1989). "Jewish Resistance and Passivity in the Face of the Holocaust". In François Furet (ed.). Unanswered questions: Nazi Germany and the genocide of the Jews (1st American ed.). New York: Schocken Books. pp. 235–251. ISBN 978-0-8052-4051-1.

- ^ Connelly, John (14 November 2012). "The Noble and the Base: Poland and the Holocaust". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ Zimmerman (2015), pp. 267–298.

- ^ Zimmerman, Joshua D. (2 July 2015). "Rethinking the Polish Underground". Interview in Yeshiva University News.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Tadeusz Piotrowski (1998). Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918-1947. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0371-4.

- ^ Eliach, Yaffa (2009) [1996]. "The Pogrom at Eishyshok". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- ^ a b Gunnar S. Paulsson (2002). Secret City: The Hidden Jews of Warsaw, 1940–1945. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09546-3.

- ^ Zimmerman (2015), p. 299.

- ^ Zimmerman (2015), p. 189.

- ^ Zimmerman (2015), p. 346.

- ^ Zimmerman (2015), pp. 314–318.

- ^ Zalesiński, Łukasz (2017). "Żołnierze akcji "Antyk" kontra komuniści". Polska Zbrojna.

- ^ Zimmerman (2015), pp. 208, 357.

- ^ (in Lithuanian) Arūnas Bubnys. Lietuvių ir lenkų pasipriešinimo judėjimai 1942–1945 m.: sąsajos ir skirtumai (Lithuanian and Polish resistance movements 1942–1945), 30 January 2004

- ^ Petersen, Roger (2002). Understanding Ethnic Violence: Fear, Hatred, and Resentment in Twentieth-century Eastern Europe. Cambridge University. p. 152. ISBN 0-521-00774-7.

- ^ a b Snyder, Timothy (2003). The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999. Yale University Press. p. 84. ISBN 0-300-10586-X.

- ^ a b Piskunowicz, Henryk (1996). "Armia Krajowa na Wileńszczyżnie". In Krzysztof Komorowski (ed.). Armia Krajowa: Rozwój organizacyjny (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Bellona. pp. 213–214. ISBN 83-11-08544-7.

- ^ (in Polish) Henryk Piskunowicz, Działalnośc zbrojna Armi Krajowej na Wileńszczyśnie w latach 1942–1944 in Zygmunt Boradyn; Andrzej Chmielarz; Henryk Piskunowicz (1997). Tomasz Strzembosz (ed.). Armia Krajowa na Nowogródczyźnie i Wileńszczyźnie (1941–1945). Warsaw: Institute of Political Sciences, Polish Academy of Sciences. pp. 40–45. ISBN 83-907168-0-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link) - ^ Jacek J. Komar (1 September 2004). "W Wilnie pojednają się dziś weterani litewskiej armii i polskiej AK" [Today in Vilnius veterans of Lithuanian army and AK will forgive each other]. Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2006.

- ^ Dovile, Budryte (30 September 2005). Taming Nationalism?. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-7546-4281-X. p.187

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Timothy Snyder, "To Resolve the Ukrainian Question Once and for All: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ukrainians in Poland, 1943–1947 Archived 16 May 2011 at Wikiwix," Journal of Cold War Studies, Spring 1999 Vol. 1 Issue 2, pp. 86–120

- ^ Mick, Christoph (7 April 2011). "Incompatible Experiences: Poles, Ukrainians and Jews in Lviv under Soviet and German Occupation, 1939-44" (PDF). Journal of Contemporary History. 46 (2): 336–363. doi:10.1177/0022009410392409. S2CID 159856277. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2023.

- ^ Marples, David R. (2007). Heroes and Villains: Creating National History in Contemporary Ukraine. Central European University Press. pp. 285–286. ISBN 978-9637326981.

- ^ Cooke, Philip; Shepherd, Ben (2014). Hitler's Europe Ablaze: Occupation, Resistance, and Rebellion during World War II. Skyhorse Publishing. pp. 336–337. ISBN 978-1-63220-159-1.

Jews who had escaped the Holocaust, and a large Polish minority, passionately hated UPA because it engaged in thorough ethnic cleansing, killing all the Jews it could find, about 50,000 Poles in Volhynia and between 20,000 and 30,000 Poles in Galicia.

- ^ Motyka (2011), pp. 447–448.

- ^ "The Effects of the Volhynian Massacres". 1943 Volhynia Massacre. Truth and Remembrance. Institute of National Remembrance. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ J. P. Himka. Interventions: Challenging the Myths of Twentieth-Century Ukrainian history. University of Alberta. 28 March 2011. p. 4

- ^ Motyka (2006), p. 324.

- ^ Motyka (2006), p. 390.

- ^ Jurij Kiriczuk, Jak za Jaremy i Krzywonosa, Gazeta Wyborcza 23 April 2003. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

- ^ Motyka (2006), p. 327.

- ^ Motyka (2006), pp. 358–360.

- ^ Motyka (2006), pp. 382, 387.

- ^ Marek Jasiak, "Overcoming Ukrainian Resistance" in: Ther, Philipp; Siljak, Ana (2001). Redrawing nations: ethnic cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944-1948. Oxford: Rowman & Littfield. p. 174.

- ^ Motyka (2016), p. 110.

- ^ Motyka (2006), p. 413.