2016 United States presidential election

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

538 members of the Electoral College 270 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 60.1%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

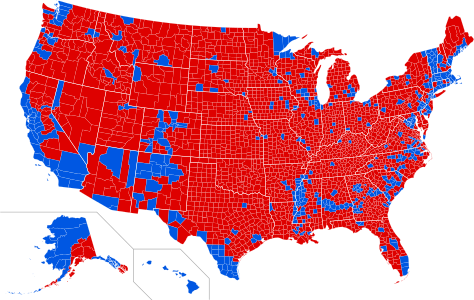

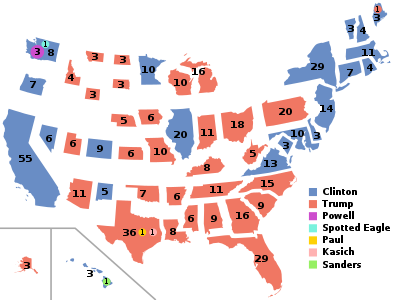

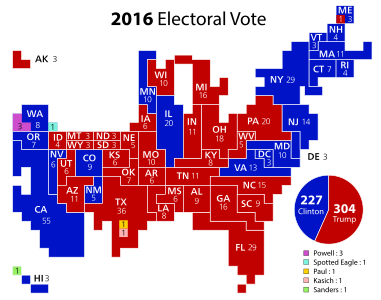

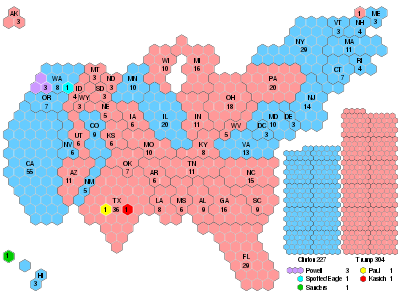

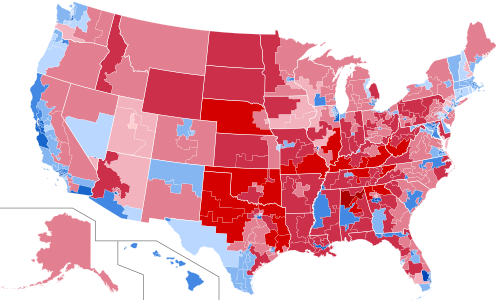

Presidential election results map. Red denotes states won by Trump/Pence and blue denotes those won by Clinton/Kaine. Numbers indicate electoral votes cast by each state and the District of Columbia. On election night, Trump won 306 electors and Clinton 232. However, because of seven faithless electors (five Democratic and two Republican), Trump received 304 votes and Clinton 227. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Republican Party | |

|---|---|

| Democratic Party | |

| Third parties | |

| Related races | |

| |

The 2016 United States presidential election was the 58th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 8, 2016. The Republican ticket of businessman Donald Trump and Indiana governor Mike Pence defeated the Democratic ticket of former secretary of state and former first lady Hillary Clinton and Virginia junior senator Tim Kaine, in what was considered one of the biggest political upsets in American history.[3] It was the fifth and most recent presidential election in which the winning candidate lost the popular vote.[2][4] It was also the sixth and most recent presidential election in U.S. history in which both major party candidates were registered in the same home state; the others have been in 1860, 1904, 1920, 1940, and 1944.

Incumbent Democratic president Barack Obama was ineligible to pursue a third term due to the term limits established by the Twenty-second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Clinton secured the nomination over U.S. senator Bernie Sanders in the Democratic primary and became the first female presidential nominee of a major American political party. Initially considered a novelty candidate, Trump emerged as the Republican front-runner, defeating several notable opponents, including U.S. senators Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, as well as governors John Kasich and Jeb Bush.[5] Trump's right-wing populist, nationalist campaign, which promised to "Make America Great Again" and opposed political correctness, illegal immigration, and many United States free-trade agreements,[6] garnered extensive free media coverage due to Trump's inflammatory comments.[7][8] Clinton emphasized her extensive political experience, denounced Trump and many of his supporters as a "basket of deplorables", bigots, and extremists, and advocated the expansion of president Barack Obama's policies, racial, LGBT, and women's rights, and inclusive capitalism.[9]

The tone of the general election campaign was widely characterized as divisive, negative, and troubling.[10][11][12] Trump faced controversy over his views on race and immigration, incidents of violence against protesters at his rallies,[13][14][15] and numerous sexual misconduct allegations including the Access Hollywood tape. Clinton's popularity and public image were tarnished by concerns about her ethics and trustworthiness,[16] and a controversy and subsequent FBI investigation regarding her improper use of a private email server while serving as secretary of state, which received more media coverage than any other topic during the campaign.[17][18] Clinton led in almost every nationwide and swing-state poll, with some predictive models giving Clinton over a 90 percent chance of winning.[19][20]

On Election Day, Trump over-performed his polls, winning several key swing states, while losing the popular vote by 2.87 million votes.[21] Trump received the majority in the Electoral College and won upset victories in the Democratic-leaning Rust Belt states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. The pivotal victory in this region, which Trump won by fewer than 80,000 votes in the three states with the combined 46 electoral votes, was considered the catalyst that won him the Electoral College vote. Trump's surprise victories were perceived to have been assisted by Clinton's lack of campaigning in the region, the rightward shift of the white working class,[22] and the influence of Sanders–Trump voters who refused to back her after Bernie Sanders dropped out.[23][24][25] Ultimately, Trump received 304 electoral votes and Clinton 227, as two faithless electors defected from Trump and five from Clinton. Trump flipped six states that had voted Democratic in 2012: Florida, Iowa, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, as well as Maine's 2nd congressional district. Trump was the first president with neither prior public service nor military experience.

With ballot access to the entire national electorate, Libertarian nominee Gary Johnson received nearly 4.5 million votes (3.27%), the highest nationwide vote share for a third-party candidate since Ross Perot in 1996,[26] while Green Party nominee Jill Stein received almost 1.45 million votes (1.06%). Independent candidate Evan McMullin received 21.4% of the vote in his home state of Utah, the highest share of the vote for a non-major party candidate in any state since 1992.[27]

On January 6, 2017, the United States Intelligence Community concluded that the Russian government had interfered in the 2016 elections,[28][29] and that it did so in order to "undermine public faith in the U.S. democratic process, denigrate Secretary Clinton, and harm her electability and potential presidency".[30] A Special Counsel investigation of alleged collusion between Russia and the Trump campaign began in May 2017,[31][32] and ended in March 2019. The investigation concluded that Russian interference in favor of Trump's candidacy occurred "in sweeping and systematic fashion" but it "did not establish that members of the Trump campaign conspired or coordinated with the Russian government".[33][34]

Background

Article Two of the Constitution of United States provides that the President and Vice President of the United States must be natural-born citizens of the United States, at least 35 years old, and residents of the United States for a period of at least 14 years.[35] Candidates for the presidency typically seek the nomination of one of the political parties, in which case each party devises a method (such as a primary election) to choose the candidate the party deems best suited to run for the position. Traditionally, the primary elections are indirect elections where voters cast ballots for a slate of party delegates pledged to a particular candidate. The party's delegates then officially nominate a candidate to run on the party's behalf. The general election in November is also an indirect election, where voters cast ballots for a slate of members of the Electoral College; these electors in turn directly elect the president and vice president.[36]

President Barack Obama, a Democrat and former U.S. senator from Illinois, was ineligible to seek reelection to a third term due to the restrictions of the American presidential term limits established by the Twenty-second Amendment; in accordance with Section 1 of the Twentieth Amendment, his term expired at noon eastern standard time on January 20, 2017.[37][38]

Both the Democratic and Republican parties, as well as third parties such as the Green and Libertarian parties, held a series of presidential primary elections and caucuses that took place between February and June 2016, staggered among the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and U.S. territories. This nominating process was also an indirect election, where voters cast ballots for a slate of delegates to a political party's nominating convention, who in turn elected their party's presidential nominee. Speculation about the 2016 campaign began almost immediately following the 2012 campaign, with New York magazine declaring that the race had begun in an article published on November 8, two days after the 2012 election.[39] On the same day, Politico released an article predicting that the 2016 general election would be between Clinton and former Florida Governor Jeb Bush, while an article in The New York Times named New Jersey Governor Chris Christie and Senator Cory Booker from New Jersey as potential candidates.[40][41]

Nominations

Republican Party

Primaries

With seventeen major candidates entering the race, starting with Ted Cruz on March 23, 2015, this was the largest presidential primary field for any political party in American history,[42] before being overtaken by the 2020 Democratic presidential primaries.[43]

Prior to the Iowa caucuses on February 1, 2016, Perry, Walker, Jindal, Graham, and Pataki withdrew due to low polling numbers. Despite leading many polls in Iowa, Trump came in second to Cruz, after which Huckabee, Paul, and Santorum withdrew due to poor performances at the ballot box. Following a sizable victory for Trump in the New Hampshire primary, Christie, Fiorina, and Gilmore abandoned the race. Bush followed suit after scoring fourth place to Trump, Rubio, and Cruz in South Carolina. On March 1, 2016, the first of four "Super Tuesday" primaries, Rubio won his first contest in Minnesota, Cruz won Alaska, Oklahoma, and his home state of Texas, and Trump won the other seven states that voted. Failing to gain traction, Carson suspended his campaign a few days later.[44] On March 15, 2016, the second "Super Tuesday", Kasich won his only contest in his home state of Ohio, and Trump won five primaries including Florida. Rubio suspended his campaign after losing his home state.[45]

Between March 16 and May 3, 2016, only three candidates remained in the race: Trump, Cruz, and Kasich. Cruz won the most delegates in four Western contests and in Wisconsin, keeping a credible path to denying Trump the nomination on the first ballot with 1,237 delegates. Trump then augmented his lead by scoring landslide victories in New York and five Northeastern states in April, followed by a decisive victory in Indiana on May 3, 2016, securing all 57 of the state's delegates. Without any further chances of forcing a contested convention, both Cruz[46] and Kasich[47] suspended their campaigns. Trump remained the only active candidate and was declared the presumptive Republican nominee by Republican National Committee chairman Reince Priebus on the evening of May 3, 2016.[48]

A 2018 study found that media coverage of Trump led to increased public support for him during the primaries. The study showed that Trump received nearly $2 billion in free media, more than double any other candidate. Political scientist John M. Sides argued that Trump's polling surge was "almost certainly" due to frequent media coverage of his campaign. Sides concluded "Trump is surging in the polls because the news media has consistently focused on him since he announced his candidacy on June 16."[49] Prior to clinching the Republican nomination, Trump received little support from establishment Republicans.[50]

Nominees

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Business and personal 45th & 47th President of the United States Tenure

Impeachments Civil and criminal prosecutions  |

||

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Vice President of the United States

U.S. Representative

for Indiana's 2nd and 6th districts Vice presidential campaigns

|

||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Donald Trump | Mike Pence | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of The Trump Organization (1971–2017) |

50th Governor of Indiana (2013–2017) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Candidates

Major candidates were determined by the various media based on common consensus. The following were invited to sanctioned televised debates based on their poll ratings.

Trump received 14,010,177 total votes in the primary. Trump, Cruz, Rubio and Kasich each won at least one primary, with Trump receiving the highest number of votes and Ted Cruz receiving the second highest.

| Candidates in this section are sorted by popular vote from the primaries | |||||||

| Ted Cruz | John Kasich | Marco Rubio | Ben Carson | Jeb Bush | Rand Paul | Chris Christie | Mike Huckabee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| U.S. senator from Texas (2013–present) |

69th Governor of Ohio (2011–2019) |

U.S. senator from Florida (2011–present) |

Dir. of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Johns Hopkins Hospital (1984–2013) |

43rd Governor of Florida (1999–2007) |

U.S. senator from Kentucky (2011–present) |

55th Governor of New Jersey (2010–2018) |

44th Governor of Arkansas (1996–2007) |

|

|

||||||

| Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign |

| W: May 3 7,811,110 votes |

W: May 4 4,287,479 votes |

W: Mar 15 3,514,124 votes |

W: Mar 4 857,009 votes |

W: Feb 20 286,634 votes |

W: Feb 3 66,781 votes |

W: Feb 10 57,634 votes |

W: Feb 1 51,436 votes |

| [51][52][53] | [54] | [55][56][57] | [58][59][60] | [61][62] | [63][64][65] | [66][67] | [68][69] |

| Carly Fiorina | Jim Gilmore | Rick Santorum | Lindsey Graham | George Pataki | Bobby Jindal | Scott Walker | Rick Perry |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CEO of Hewlett-Packard (1999–2005) |

68th Governor of Virginia (1998–2002) |

U.S. senator from Pennsylvania (1995–2007) |

U.S. senator from South Carolina (2003–present) |

53rd Governor of New York (1995–2006) |

55th Governor of Louisiana (2008–2016) |

45th Governor of Wisconsin (2011–2019) |

47th Governor of Texas (2000–2015) |

|

|

| |||||

| Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign |

| W: Feb 10 40,577 votes |

W: Feb 12 18,364 votes |

W: Feb 3 16,622 votes |

W: December 21, 2015 5,666 votes |

W: December 29, 2015 2,036 votes |

W: November 17, 2015 222 votes |

W: September 21, 2015 1 write-in vote in New Hampshire |

W: September 11, 2015 1 write-in vote in New Hampshire |

| [70][71] | [72][73] | [74][75] | [76][77] | [78] | [79][80] | [81][82][83] | [83][84][85] |

Vice presidential selection

Trump turned his attention towards selecting a running mate after he became the presumptive nominee on May 4, 2016.[86] In mid-June, Eli Stokols and Burgess Everett of Politico reported that the Trump campaign was considering New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich from Georgia, Senator Jeff Sessions of Alabama, and Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin.[87] A June 30 report from The Washington Post also included Senators Bob Corker from Tennessee, Richard Burr from North Carolina, Tom Cotton from Arkansas, Joni Ernst from Iowa, and Indiana governor Mike Pence as individuals still being considered for the ticket.[88] Trump also said he was considering two military generals for the position, including retired Lieutenant General Michael Flynn.[89]

In July 2016, it was reported that Trump had narrowed his list of possible running mates down to three: Christie, Gingrich, and Pence.[90]

On July 14, 2016, several major media outlets reported that Trump had selected Pence as his running mate. Trump confirmed these reports in a message Twitter on July 15, 2016, and formally made the announcement the following day in New York.[91][92] On July 19, the second night of the 2016 Republican National Convention, Pence won the Republican vice presidential nomination by acclamation.[93]

Democratic Party

Primaries

Former secretary of state Hillary Clinton, who also served in the U.S. Senate and was the first lady of the United States, became the first Democrat in the field to formally launch a major candidacy for the presidency with an announcement on April 12, 2015, via a video message.[94] While nationwide opinion polls in 2015 indicated that Clinton was the front-runner for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination, she faced strong challenges from independent Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont,[95] who became the second major candidate when he formally announced on April 30, 2015, that he was running for the Democratic nomination.[96] September 2015 polling numbers indicated a narrowing gap between Clinton and Sanders.[95][97][98] On May 30, 2015, former governor of Maryland Martin O'Malley was the third major candidate to enter the Democratic primary race,[99] followed by former independent governor and Republican senator of Rhode Island Lincoln Chafee on June 3, 2015,[100][101] former Virginia senator Jim Webb on July 2, 2015,[102] and former Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig on September 6, 2015.[103]

On October 20, 2015, Webb announced his withdrawal from the primaries, and explored a potential independent run.[104] The next day, Vice President Joe Biden decided not to run, ending months of speculation, stating, "While I will not be a candidate, I will not be silent."[105][106] On October 23, Chafee withdrew, stating that he hoped for "an end to the endless wars and the beginning of a new era for the United States and humanity."[107] On November 2, after failing to qualify for the second DNC-sanctioned debate after adoption of a rule change negated polls which before might have necessitated his inclusion in the debate, Lessig withdrew as well, narrowing the field to Clinton, O'Malley, and Sanders.[108]

On February 1, 2016, in an extremely close contest, Clinton won the Iowa caucuses by a margin of 0.2 points over Sanders. After winning no delegates in Iowa, O'Malley withdrew from the presidential race that day. On February 9, Sanders bounced back to win the New Hampshire primary with 60% of the vote. In the remaining two February contests, Clinton won the Nevada caucuses with 53% of the vote and scored a decisive victory in the South Carolina primary with 73% of the vote.[109][110] On March 1, eleven states participated in the first of four "Super Tuesday" primaries. Clinton won Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Massachusetts, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia and 504 pledged delegates, while Sanders won Colorado, Minnesota, Oklahoma, and his home state of Vermont and 340 delegates. The following weekend, Sanders won victories in Kansas, Nebraska, and Maine with 15- to 30-point margins, while Clinton won the Louisiana primary with 71% of the vote. On March 8, despite never having a lead in the Michigan primary, Sanders won by a small margin of 1.5 points and outperforming polls by over 19 points, while Clinton won 83% of the vote in Mississippi.[111] On March 15, the second "Super Tuesday", Clinton won in Florida, Illinois, Missouri, North Carolina, and Ohio. Between March 22 and April 9, Sanders won six caucuses in Idaho, Utah, Alaska, Hawaii, Washington, and Wyoming, as well as the Wisconsin primary, while Clinton won the Arizona primary. On April 19, Clinton won the New York primary with 58% of the vote. On April 26, in the third "Super Tuesday" dubbed the "Acela primary", she won contests in Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, while Sanders won in Rhode Island. Over the course of May, Sanders accomplished another surprise win in the Indiana primary[112] and also won in West Virginia and Oregon, while Clinton won the Guam caucus and Kentucky primary (and also non-binding primaries in Nebraska and Washington).

On June 4 and 5, Clinton won two victories in the Virgin Islands caucus and Puerto Rico primary. On June 6, 2016, the Associated Press and NBC News reported that Clinton had become the presumptive nominee after reaching the required number of delegates, including pledged delegates and superdelegates, to secure the nomination, becoming the first woman to ever clinch the presidential nomination of a major U.S. political party.[113] On June 7, Clinton secured a majority of pledged delegates after winning primaries in California, New Jersey, New Mexico, and South Dakota, while Sanders won only Montana and North Dakota. Clinton also won the final primary in the District of Columbia on June 14. At the conclusion of the primary process, Clinton had won 2,204 pledged delegates (54% of the total) awarded by the primary elections and caucuses, while Sanders had won 1,847 (46%). Out of the 714 unpledged delegates or "superdelegates" who were set to vote in the convention in July, Clinton received endorsements from 560 (78%), while Sanders received 47 (7%).[114]

Although Sanders had not formally dropped out of the race, he announced on June 16, 2016, that his main goal in the coming months would be to work with Clinton to defeat Trump in the general election.[115] On July 8, appointees from the Clinton campaign, the Sanders campaign, and the Democratic National Committee negotiated a draft of the party's platform.[116] On July 12, Sanders formally endorsed Clinton at a rally in New Hampshire in which he appeared with her.[117] Sanders then went on to headline 39 campaign rallies on behalf of Clinton in 13 key states.[118]

Nominees

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

First Lady of the United States

U.S. Senator from New York

U.S. Secretary of State

2008 presidential campaign 2016 presidential campaign Organizations

|

||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hillary Clinton | Tim Kaine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 67th U.S. Secretary of State (2009–2013) |

U.S. Senator from Virginia (2013–present) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Candidates

The following candidates were frequently interviewed by major broadcast networks and cable news channels or were listed in publicly published national polls. Lessig was invited to one forum, but withdrew when rules were changed which prevented him from participating in officially sanctioned debates.

Clinton received 16,849,779 votes in the primary.

| Candidates in this section are sorted by popular vote from the primaries | ||||||||

| Bernie Sanders | Martin O'Malley | Lawrence Lessig | Jim Webb | Lincoln Chafee | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| U.S. senator from Vermont (2007–present) |

61st governor of Maryland (2007–2015) |

Harvard Law professor (2009–2016) |

U.S. senator from Virginia (2007–2013) |

74th Governor of Rhode Island (2011–2015) | ||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | ||||

| LN: July 26, 2016 13,167,848 votes |

W: February 1, 2016 110,423 votes |

W: November 2, 2015 4 write-in votes in New Hampshire |

W: October 20, 2015 2 write-in votes in New Hampshire |

W: October 23, 2015 0 votes | ||||

| [119] | [120][121] | [108] | [122] | [123] | ||||

Vice presidential selection

In April 2016, the Clinton campaign began to compile a list of 15 to 20 individuals to vet for the position of running mate, even though Sanders continued to challenge Clinton in the Democratic primaries.[124] In mid-June, The Wall Street Journal reported that Clinton's shortlist included Representative Xavier Becerra from California, Senator Cory Booker from New Jersey, Senator Sherrod Brown from Ohio, Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julián Castro from Texas, Mayor of Los Angeles Eric Garcetti from California, Senator Tim Kaine from Virginia, Labor Secretary Tom Perez from Maryland, Representative Tim Ryan from Ohio, and Senator Elizabeth Warren from Massachusetts.[125] Subsequent reports stated that Clinton was also considering Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack, retired Admiral James Stavridis, and Governor John Hickenlooper of Colorado.[126] In discussing her potential vice presidential choice, Clinton said the most important attribute she looked for was the ability and experience to immediately step into the role of president.[126]

On July 22, Clinton announced that she had chosen Senator Tim Kaine from Virginia as her running mate.[127] The delegates at the 2016 Democratic National Convention, which took place July 25–28, formally nominated the Democratic ticket.

Minor parties and independents

Third party and independent candidates who obtained more than 100,000 votes nationally or on ballot in at least 15 states are listed separately.

Libertarian Party

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Governor of New Mexico

Presidential campaigns

|

||

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Pre-governorship

Governor of Massachusetts

|

||

- Gary Johnson, 29th Governor of New Mexico. Vice-presidential nominee: Bill Weld, 68th Governor of Massachusetts

- Additional Party Endorsements: Independence Party of New York

Ballot access to all 538 electoral votes

Nominees

| |

|---|---|

| Gary Johnson | Bill Weld |

| for President | for Vice President |

|

|

| 29th Governor of New Mexico (1995–2003) |

68th Governor of Massachusetts (1991–1997) |

| |

Green Party

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Massachusetts campaigns

Presidential campaigns

Political party affiliations

|

||

- Jill Stein, physician from Lexington, Massachusetts. Vice-presidential nominee: Ajamu Baraka, activist from Washington, D.C.

Ballot access to 480 electoral votes (522 with write-in):[128] map

- As write-in: Georgia, Indiana, North Carolina[129][130]

- No ballot access: Nevada, South Dakota, Oklahoma[129][131]

Nominees

| |

|---|---|

| Jill Stein | Ajamu Baraka |

| for President | for Vice President |

|

|

| Physician from Lexington, Massachusetts |

Activist from Washington, D.C. |

| |

Constitution Party

- Darrell Castle, attorney from Memphis, Tennessee. Vice-presidential nominee: Scott Bradley, businessman from Utah

Ballot access to 207 electoral votes (451 with write-in):[132][133] map

- As write-in: Alabama, Arizona, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Virginia[132][134][135][136][137]

- No ballot access: California, District of Columbia, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Oklahoma[132]

Nominees

| |

| Darrell Castle | Scott Bradley |

|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President |

|

|

| Attorney from Memphis, Tennessee |

Businessman from Utah |

| Campaign | |

| |

| [138] | |

Independent

- Evan McMullin, chief policy director for the House Republican Conference. Vice-presidential nominee: Mindy Finn, president of Empowered Women.

- Additional Party Endorsement: Independence Party of Minnesota, South Carolina Independence Party

Ballot access to 84 electoral votes (451 with write-in):[139] map

- As write-in: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin[139][140][141][142][143][144][145]

- No ballot access: District of Columbia, Florida, Hawaii, Indiana, Mississippi, Nevada, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Wyoming

In some states, Evan McMullin's running mate was listed as Nathan Johnson on the ballot rather than Mindy Finn, although Nathan Johnson was intended to only be a placeholder until an actual running mate was chosen.[146]

| 2016 Independent ticket | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Evan McMullin | Mindy Finn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chief policy director for the House Republican Conference (2015–2016) |

President of Empowered Women (2015–present) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [147] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Party for Socialism and Liberation

| Gloria La Riva | Eugene Puryear |

|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President |

|

|

| Newspaper printer and activist from California | Activist from Washington, D.C. |

| |

Other nominations

| Party | Presidential nominee | Vice presidential nominee | Attainable electors (write-in) |

Popular vote | States with ballot access (write-in) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party for Socialism and Liberation |

Gloria La Riva Newspaper printer and activist from California |

Eugene Puryear Activist from Washington, D.C. |

112 (226) map |

74,402 (0.05%) |

California, Colorado, Iowa, Louisiana, New Jersey, New Mexico, Vermont, Washington[150][151] (Alabama, Connecticut, Delaware, Kansas, Maryland, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, West Virginia)[141][142][144][136][152][153][154][155][156] |

| Independent | Richard Duncan Real Estate Agent from Ohio |

Ricky Johnson Preacher from Pennsylvania |

18 (173) |

24,307 (0.02%) |

Ohio[157] (Alabama, Alaska, Delaware, Florida, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, West Virginia)[136][152][153][158][159][154][155][151][156][160][161][162][163] |

General election campaign

Beliefs and policies of candidates

Hillary Clinton focused her candidacy on several themes, including raising middle class incomes, expanding women's rights, instituting campaign finance reform, and improving the Affordable Care Act. In March 2016, she laid out a detailed economic plan basing her economic philosophy on inclusive capitalism, which proposed a "clawback" that rescinds tax cuts and other benefits for companies that move jobs overseas; with provision of incentives for companies that share profits with employees, communities and the environment, rather than focusing on short-term profits to increase stock value and rewarding shareholders; as well as increasing collective bargaining rights; and placing an "exit tax" on companies that move their headquarters out of the U.S. in order to pay a lower tax rate overseas.[164] Clinton promoted equal pay for equal work to address current alleged shortfalls in how much women are paid to do the same jobs men do,[165] promoted explicitly focus on family issues and support of universal preschool,[166] expressed support for the right to same-sex marriage,[166] and proposed allowing undocumented immigrants to have a path to citizenship stating that it "[i]s at its heart a family issue."[167]

Donald Trump's campaign drew heavily on his personal image, enhanced by his previous media exposure.[168] The primary slogan of the Trump campaign, extensively used on campaign merchandise, was Make America Great Again. The red baseball cap with the slogan emblazoned on the front became a symbol of the campaign and has been frequently donned by Trump and his supporters.[169] Trump's right-wing populist positions—reported by The New Yorker to be nativist, protectionist, and semi-isolationist—differ in many ways from traditional U.S. conservatism.[170] He opposed many free trade deals and military interventionist policies that conservatives generally support, and opposed cuts in Medicare and Social Security benefits. Moreover, he has insisted that Washington is "broken" and can be fixed only by an outsider.[171][172][173] Support for Trump was high among working and middle-class white male voters with annual incomes of less than $50,000 and no college degree.[174] This group, particularly those without a high-school diploma, suffered a decline in their income in recent years.[175] According to The Washington Post, support for Trump is higher in areas with a higher mortality rate for middle-aged white people.[176] A sample of interviews with more than 11,000 Republican-leaning respondents from August to December 2015 found that Trump at that time found his strongest support among Republicans in West Virginia, followed by New York, and then followed by six Southern states.[177]

Media coverage

Clinton had an uneasy—and, at times, adversarial—relationship with the press throughout her life in public service.[178] Weeks before her official entry as a presidential candidate, Clinton attended a political press corps event, pledging to start fresh on what she described as a "complicated" relationship with political reporters.[179] Clinton was initially criticized by the press for avoiding taking their questions,[180][181] after which she provided more interviews.

In contrast, Trump benefited from free media more than any other candidate. From the beginning of his campaign through February 2016, Trump received almost $2 billion in free media attention, twice the amount that Clinton received.[182] According to data from the Tyndall Report, which tracks nightly news content, through February 2016, Trump alone accounted for more than a quarter of all 2016 election coverage on the evening newscasts of NBC, CBS and ABC, more than all the Democratic campaigns combined.[183][184][185] Observers noted Trump's ability to garner constant mainstream media coverage "almost at will."[186] However, Trump frequently criticized the media for writing what he alleged to be false stories about him[187] and he has called upon his supporters to be "the silent majority."[188] Trump also said the media "put false meaning into the words I say", and says he does not mind being criticized by the media as long as they are honest about it.[189][190]

Controversies

According to a wide range of representative polls, both Clinton and Trump had significant net-unfavorability ratings, and their controversial reputations set the tone of the campaign.[191]

Clinton's practice during her time as Secretary of State of using a private email address and server, in lieu of State Department servers, gained widespread public attention back in March 2015.[192] Concerns were raised about security and preservation of emails, and the possibility that laws may have been violated.[193] After allegations were raised that some of the emails in question fell into this so-called "born classified" category, an FBI probe was initiated regarding how classified information was handled on the Clinton server.[194][195][196][197] The FBI probe was concluded on July 5, 2016, with a recommendation of no charges, a recommendation that was followed by the Justice Department.

Also, on September 9, 2016, Clinton said: "You know, just to be grossly generalistic, you could put half of Trump's supporters into what I call the basket of deplorables. They're racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamophobic—you name it,"[198] adding "But that 'other' basket of people are people who feel the government has let them down, the economy has let them down, nobody cares about them, nobody worries about what happens to their lives and their futures; and they're just desperate for change...Those are people we have to understand and empathize with as well."[199]

Donald Trump criticized her remark as insulting his supporters.[200][201] The following day Clinton expressed regret for saying "half", while insisting that Trump had deplorably amplified "hateful views and voices."[202] Previously on August 25, 2016, Clinton gave a speech criticizing Trump's campaign for using "racist lies" and allowing the alt-right to gain prominence.[203]

On September 11, 2016, Clinton left a 9/11 memorial event early due to illness.[204] Video footage of Clinton's departure showed Clinton becoming unsteady on her feet and being helped into a van.[205] Later that evening, Clinton reassured reporters that she was "feeling great."[206] After initially stating that Clinton had become overheated at the event, her campaign later added that she had been diagnosed with pneumonia two days earlier.[205] The media criticized the Clinton campaign for a lack of transparency regarding Clinton's illness.[205] Clinton cancelled a planned trip to California due to her illness. The episode drew renewed public attention to questions about Clinton's health.[206]

On the other side, on October 7, 2016, video and accompanying audio were released by The Washington Post in which Trump referred obscenely to women in a 2005 conversation with Billy Bush while they were preparing to film an episode of Access Hollywood. In the recording, Trump described his attempts to initiate a sexual relationship with a married woman and added that women would allow male celebrities to grope their genitalia (Trump used the phrase "grab 'em by the pussy"). The audio was met with a reaction of disbelief and disgust from the media.[207][208][209] Following the revelation, Trump's campaign issued an apology, stating that the video was of a private conversation from "many years ago."[210] The incident was condemned by numerous prominent Republicans like Reince Priebus, Mitt Romney, John Kasich, Jeb Bush[211] and the Speaker of the House Paul Ryan.[212] Many believed the video had doomed Trump's chances for election. By October 8, several dozen Republicans had called for Trump to withdraw from the campaign and let Pence and Condoleezza Rice head the ticket.[213] Trump insisted he would never drop out, but apologized for his remarks.[214][215]

Trump also delivered strong and controversial statements towards Muslims and Islam on the campaign trail, saying, "I think Islam hates us."[216] He was criticized and also supported for his statement at a rally declaring, "Donald J. Trump is calling for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country's representatives can figure out what is going on."[217] Additionally, Trump announced that he would "look into" surveilling mosques, and mentioned potentially going after the families of domestic terrorists in the wake of the San Bernardino shooting.[218] His strong rhetoric towards Muslims resulted in leadership from both parties condemning his statements. However, many of his supporters shared their support for his proposed travel ban, despite the backlash.[217]

Throughout the campaign, Trump indicated in interviews, speeches, and Twitter posts that he would refuse to recognize the outcome of the election if he was defeated.[219][220] Trump falsely stated that the election would be rigged against him.[221][222] During the final presidential debate of 2016, Trump refused to tell Fox News anchor Chris Wallace whether or not he would accept the election results.[223] The rejection of election results by a major nominee would have been unprecedented at the time as no major presidential candidate had ever refused to accept the outcome of an election until Trump did so himself in the following 2020 presidential election.[224][225]

The ongoing controversy of the election made third parties attract voters' attention. On March 3, 2016, Libertarian Gary Johnson addressed the Conservative Political Action Conference in Washington, DC, touting himself as the third-party option for anti-Trump Republicans.[226][227] In early May, some commentators opined that Johnson was moderate enough to pull votes away from both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump who were very disliked and polarizing.[228] Johnson also began to get time on national television, being invited on ABC News, NBC News, CBS News, CNN, Fox News, MSNBC, Bloomberg, and many other networks.[229] In September and October 2016, Johnson suffered a "string of damaging stumbles when he has fielded questions about foreign affairs."[230][231] On September 8, Johnson, when he appeared on MSNBC's Morning Joe, was asked by panelist Mike Barnicle, "What would you do, if you were elected, about Aleppo?" (referring to a war-torn city in Syria). Johnson responded, "And what is Aleppo?"[232] His response prompted widespread attention, much of it negative.[232][233] Later that day, Johnson said that he had "blanked" and that he did "understand the dynamics of the Syrian conflict—I talk about them every day."[233]

On the other hand, Green Party candidate Jill Stein said the Democratic and Republican parties are "two corporate parties" that have converged into one.[234] Concerned by the rise of the far right internationally and the tendency towards neoliberalism within the Democratic Party, she has said, "The answer to neofascism is stopping neoliberalism. Putting another Clinton in the White House will fan the flames of this right-wing extremism."[235][236]

In response to Johnson's growing poll numbers, the Clinton campaign and Democratic allies increased their criticism of Johnson in September 2016, warning that "a vote for a third party is a vote for Donald Trump" and deploying Senator Bernie Sanders (Clinton's former primary rival, who supported her in the general election) to win over voters who might be considering voting for Johnson or for Stein.[237]

On October 28, eleven days before the election, FBI Director James Comey informed Congress that the FBI was analyzing additional Clinton emails obtained during its investigation of an unrelated case.[238][239] On November 6, he notified Congress that the new emails did not change the FBI's earlier conclusion.[240][241] In the week following the "Comey Letter" of October 28, Clinton's lead dropped by 3 percentage points, leading some commentators - including Clinton herself - to conclude that this letter cost her the election,[242][243][244] though there are dissenting views.[243]

Ballot access

| Presidential ticket | Party | Ballot access | Votes[2][245] | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| States | Electors | % of voters | ||||

| Trump / Pence | Republican | 50 + DC | 538 | 100% | 62,984,828 | 46.09% |

| Clinton / Kaine | Democratic | 50 + DC | 538 | 100% | 65,853,514 | 48.18% |

| Johnson / Weld | Libertarian | 50 + DC | 538 | 100% | 4,489,341 | 3.28% |

| Stein / Baraka | Green | 44 + DC | 480 | 89% | 1,457,218 | 1.07% |

| McMullin / Finn | Independent | 11 | 84 | 15% | 731,991 | 0.54% |

| Castle / Bradley | Constitution | 24 | 207 | 39% | 203,090 | 0.15% |

- Candidates in bold were on ballots representing 270 electoral votes, without needing write-in states.

- All other candidates were on the ballots of fewer than 25 states, but had write-in access greater than 270.

Party conventions

Republican Party

Democratic Party

- July 25–28, 2016: Democratic National Convention was held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[248]

Libertarian Party

Green Party

Constitution Party

- April 13–16, 2016: Constitution Party National Convention was held in Salt Lake City, Utah.[253]

Campaign finance

Wall Street spent a record $2 billion trying to influence the 2016 United States presidential election.[254][255]

The following table is an overview of the money used in the campaign as it is reported to Federal Election Commission (FEC) and released in September 2016. Outside groups are independent expenditure-only committees—also called PACs and SuperPACs. The sources of the numbers are the FEC and OpenSecrets.[256] Some spending totals are not available, due to withdrawals before the FEC deadline. As of September 2016[update], ten candidates with ballot access have filed financial reports with the FEC.

| Candidate | Campaign committee (as of December 9) | Outside groups (as of December 9) | Total spent | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Money raised | Money spent | Cash on hand | Debt | Money raised | Money spent | Cash on hand | ||

| Donald Trump[257][258] | $350,668,435 | $343,056,732 | $7,611,702 | $0 | $100,265,563 | $97,105,012 | $3,160,552 | $440,161,744 |

| Hillary Clinton[259][260] | $585,699,061 | $585,580,576 | $323,317 | $182 | $206,122,160 | $205,144,296 | $977,864 | $790,724,872 |

| Gary Johnson[261][262] | $12,193,984 | $12,463,110 | $6,299 | $0 | $1,386,971 | $1,314,095 | $75,976 | $13,777,205 |

| Rocky De La Fuente[263] | $8,075,959 | $8,074,913 | $1,046 | $8,058,834 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $8,074,913 |

| Jill Stein[264][265] | $11,240,359 | $11,275,899 | $105,132 | $87,740 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $11,275,899 |

| Evan McMullin[266] | $1,644,102 | $1,642,165 | $1,937 | $644,913 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $1,642,165 |

| Darrell Castle[267] | $72,264 | $68,063 | $4,200 | $4,902 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $68,063 |

| Gloria La Riva[268] | $31,408 | $32,611 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $32,611 |

| Monica Moorehead[269] | $14,313 | $15,355 | -$1,043 | -$5,500[A] | $0 | $0 | $0 | $15,355 |

| Peter Skewes[270] | $8,216 | $8,216 | $0 | $4,000 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $8,216 |

- ^ Debt owed to committee

Voting rights

The 2016 presidential election was the first in 50 years without all the protections of the original Voting Rights Act.[271] Fourteen states had new voting restrictions in place, including swing states such as Virginia and Wisconsin.[272][273][274][275][276]

Election administration

Among states that offered early in-person voting to all voters in 2016, 27 percent of all votes were cast early in person. Across states where mail voting was available to all voters, 34 percent of all votes were cast by mail. Nationwide, a total of 40 percent of votes were cast before Election Day in the 2016 general election.[277]

Newspaper endorsements

Clinton was endorsed by The New York Times,[278] the Los Angeles Times,[279] the Houston Chronicle,[280] the San Jose Mercury News,[281] the Chicago Sun-Times[282] and the New York Daily News[283] editorial boards. Several papers which endorsed Clinton, such as the Houston Chronicle,[280] The Dallas Morning News,[284] The San Diego Union-Tribune,[285] The Columbus Dispatch[286] and The Arizona Republic,[287] endorsed their first Democratic candidate for many decades. The Atlantic, which has been in circulation since 1857, gave Clinton its third-ever endorsement (after Abraham Lincoln and Lyndon Johnson).[288]

Trump, who frequently criticized the mainstream media, was not endorsed by the vast majority of newspapers.[289][290] The Las Vegas Review-Journal,[291] The Florida Times-Union,[292] and the tabloid National Enquirer were his highest profile supporters.[293] USA Today, which had not endorsed any candidate since it was founded in 1982, broke tradition by giving an anti-endorsement against Trump, declaring him "unfit for the presidency."[294][295]

Gary Johnson received endorsements from several major daily newspapers, including the Chicago Tribune,[296] and the Richmond Times-Dispatch.[297] Other traditionally Republican papers, including the New Hampshire Union Leader, which had endorsed the Republican nominee in every election for the last 100 years,[298] and The Detroit News, which had not endorsed a non-Republican in its 143 years,[299] endorsed Gary Johnson.

Involvement of other countries

Russian involvement

On December 9, 2016, the Central Intelligence Agency issued an assessment to lawmakers in the US Senate, stating that a Russian entity hacked the DNC and John Podesta's emails to assist Donald Trump. The Federal Bureau of Investigation agreed.[300] President Barack Obama ordered a "full review" into such possible intervention.[301] Director of National Intelligence James R. Clapper in early January 2017 testified before a Senate committee that Russia's meddling in the 2016 presidential campaign went beyond hacking, and included disinformation and the dissemination of fake news, often promoted on social media.[302] Facebook revealed that during the 2016 United States presidential election, a Russian company funded by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Russian businessman with ties to Vladimir Putin,[303] had purchased advertisements on the website for US$100,000,[304] 25% of which were geographically targeted to the U.S.[305]

President-elect Trump originally called the report fabricated.[306] Julian Assange said the Russian government was not the source of the documents.[307] Days later, Trump said he could be convinced of the Russian hacking "if there is a unified presentation of evidence from the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other agencies."[308]

Several U.S. senators—including Republicans John McCain, Richard Burr, and Lindsey Graham—demanded a congressional investigation.[309] The Senate Intelligence Committee announced the scope of their official inquiry on December 13, 2016, on a bipartisan basis; work began on January 24, 2017.[310]

A formal Special Counsel investigation headed by former FBI director Robert Mueller was initiated in May 2017 to uncover the detailed interference operations by Russia, and to determine whether any people associated with the Trump campaign were complicit in the Russian efforts. When questioned by Chuck Todd on Meet the Press on March 5, 2017, Clapper declared that intelligence investigations on Russian interference performed by the FBI, CIA, NSA and his ODNI office had found no evidence of collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia.[311] Mueller concluded his investigation on March 22, 2019, by submitting his report to Attorney General William Barr.[312]

On March 24, 2019, Barr submitted a letter describing Mueller's conclusions,[313][314] and on April 18, 2019, a redacted version of the Mueller report was released to the public. It concluded that Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election did occur "in sweeping and systematic fashion" and "violated U.S. criminal law."[315][316]

The first method detailed in the final report was the usage of the Internet Research Agency, waging "a social media campaign that favored presidential candidate Donald J. Trump and disparaged presidential candidate Hillary Clinton."[317] The Internet Research Agency also sought to "provoke and amplify political and social discord in the United States."[318]

The second method of Russian interference saw the Russian intelligence service, the GRU, hacking into email accounts owned by volunteers and employees of the Clinton presidential campaign, including that of campaign chairman John Podesta, and also hacking into "the computer networks of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) and the Democratic National Committee (DNC)."[319] As a result, the GRU obtained hundreds of thousands of hacked documents, and the GRU proceeded by arranging releases of damaging hacked material via the WikiLeaks organization and also GRU's personas "DCLeaks" and "Guccifer 2.0."[320][321] To establish whether a crime was committed by members of the Trump campaign with regard to Russian interference, the special counsel's investigators "applied the framework of conspiracy law", and not the concept of "collusion", because collusion "is not a specific offense or theory of liability found in the United States Code, nor is it a term of art in federal criminal law."[322][323] They also investigated if members of the Trump campaign "coordinated" with Russia, using the definition of "coordination" as having "an agreement—tacit or express—between the Trump campaign and the Russian government on election interference." Investigators further elaborated that merely having "two parties taking actions that were informed by or responsive to the other's actions or interests" was not enough to establish coordination.[324]

The Mueller report writes that the investigation "identified numerous links between the Russian government and the Trump campaign", found that Russia "perceived it would benefit from a Trump presidency" and that the 2016 Trump presidential campaign "expected it would benefit electorally" from Russian hacking efforts. Ultimately, "the investigation did not establish that members of the Trump campaign conspired or coordinated with the Russian government in its election interference activities."[325][326]

However, investigators had an incomplete picture of what had really occurred during the 2016 campaign, due to some associates of Trump campaign providing either false, incomplete or declined testimony, as well as having deleted, unsaved or encrypted communications. As such, the Mueller report "cannot rule out the possibility" that information then unavailable to investigators would have presented different findings.[327][328] In March 2020, the US Justice Department dropped its prosecution of two Russian firms linked to interference in the 2016 election.[329][303]

Other countries

Special Council Robert Mueller also investigated the Trump campaign's alleged ties to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Qatar, Israel, and China.[330][331] According to The Times of Israel, Trump's longtime confidant Roger Stone "was in contact with one or more apparently well-connected Israelis at the height of the 2016 US presidential campaign, one of whom warned Stone that Trump was 'going to be defeated unless we intervene' and promised 'we have critical intell [sic].'"[332][333]

The Justice Department accused George Nader of providing $3.5 million in illicit campaign donations to Hillary Clinton before the elections and to Trump after he won the elections. According to The New York Times, this was an attempt by the government of United Arab Emirates to influence the election.[334]

In December 2018, a Ukrainian court ruled that prosecutors in Ukraine had meddled in the 2016 election by releasing damaging information on Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort.[335]

Voice of America reported in April 2020 that "U.S. intelligence agencies concluded the Chinese hackers meddled in both the 2016 and 2018 elections."[336]

In July 2021, the US federal prosecutors accused Trump's former adviser Tom Barrack for being an unregistered foreign lobbying agent for the United Arab Emirates during the 2016 presidential campaign of Donald Trump.[337] In 2022, Barrack was found not guilty on all charges.[338]

Notable expressions, phrases, and statements

By Trump and Republicans:

- "Because you'd be in jail": Off-the-cuff quip by Donald Trump during the second presidential debate, in rebuttal to Clinton stating it was "awfully good someone with the temperament of Donald Trump is not in charge of the law in our country."[339]

- "Big-league": A word used by Donald Trump most notably during the first presidential debate, misheard by many as bigly, when he said, "I'm going to cut taxes big-league, and you're going to raise taxes big-league."[340][341]

- "Build the wall": A chant used at many Trump campaign rallies, and Donald Trump's corresponding promise of the Mexican Border Wall.[340]

- "Drain the swamp": A phrase Donald Trump invoked late in the campaign to describe what needs to be done to fix problems in the federal government. Trump acknowledged that the phrase was suggested to him, and he was initially skeptical about using it.[342]

- "Grab 'em by the pussy" and "when you're a star, they let you do it": A remark made by Trump during a 2005 behind-the-scenes interview with presenter Billy Bush on NBCUniversal's Access Hollywood, which was released during the campaign.

- "I like people who weren't captured": Donald Trump's criticism of Senator John McCain, who was held as a prisoner of war by North Vietnam during the Vietnam War.[343][344]

- "Lock her up": A chant first used at the Republican convention to claim that Hillary Clinton was guilty of a crime. The chant was later used at many Trump campaign rallies and even against other politicians critical of Trump, such as Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer[345][346] and (as "lock him up") against President Joe Biden.[347] The phrase would also see use in the 2024 United States presidential election by opponents of Trump in reference to his indictments.

- "Make America Great Again": Donald Trump's campaign slogan.

- "Mexico will pay for it": Trump's campaign promise that if elected he will build a wall on the border between the US and Mexico, with Mexico financing the project.[348][349]

- Nicknames used by Trump to deride his opponents: These include "Crooked Hillary", "Little Marco", "Low-energy Jeb", and "Lyin' Ted."

- "Russia, if you're listening": Used by Donald Trump to invite Russia to "find the 30,000 emails that are missing" (from Hillary Clinton) during a July 2016 news conference.[350]

- "Such a nasty woman": Donald Trump's response to Hillary Clinton after her saying that her proposed rise in Social Security contributions would also include Trump's Social Security contributions, "assuming he can't figure out how to get out of it."[340] Later reappropriated by supporters of Clinton[351][352][353] and liberal feminists.[354][355][356]

- "They're not sending their best...They're bringing drugs. They're bringing crime. They're rapists. And some, I assume, are good people": Donald Trump's controversial description of those crossing the Mexico–United States border during the June 2015 launch of his campaign.[357]

- "What the hell do you have to lose?": Said by Donald Trump to inner-city African Americans at rallies starting on August 19, 2016.[358][359]

By Clinton and Democrats:

- "Basket of deplorables": A controversial phrase coined by Hillary Clinton to describe half of those who support Trump.

- "I'm with her": Clinton's unofficial campaign slogan ("Stronger Together" was the official slogan).[360]

- "What, like with a cloth or something?": Said by Hillary Clinton in response to being asked whether she "wiped" her emails during an August 2015 press conference.[343]

- "Why aren't I 50 points ahead?": Rhetorical question asked by Hillary Clinton during a video address to the Laborers' International Union of North America on September 21, 2016, which was then turned into an opposition ad by the Trump campaign.[361][362]

- "When they go low, we go high": Said by then-first lady Michelle Obama during her Democratic convention speech.[340] This was later inverted by Eric Holder.[363]

- "Feel the Bern": A phrase chanted by supporters of the Bernie Sanders campaign which was officially adopted by his campaign.[364]

- "Pokémon Go to the polls": An often-ridiculed phrase coined by Hillary Clinton to encourage young people to go to the polls.[365]

Debates

Primary election

General election

The Commission on Presidential Debates (CPD), a non-profit organization, hosted debates between qualifying presidential and vice-presidential candidates. According to the commission's website, to be eligible to opt to participate in the anticipated debates, "in addition to being Constitutionally eligible, candidates must appear on a sufficient number of state ballots to have a mathematical chance of winning a majority vote in the Electoral College, and have a level of support of at least 15 percent of the national electorate as determined by five selected national public opinion polling organizations, using the average of those organizations' most recently publicly-reported results at the time of the determination."[366]

The three locations (Hofstra University, Washington University in St. Louis, University of Nevada, Las Vegas) chosen to host the presidential debates, and the one location (Longwood University) selected to host the vice presidential debate, were announced on September 23, 2015. The site of the first debate was originally designated as Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio; however, due to rising costs and security concerns, the debate was moved to Hofstra University in Hempstead, New York.[367]

On August 19, Kellyanne Conway, Trump's campaign manager confirmed that Trump would participate in a series of three debates.[368][369][370][371] Trump had complained two of the scheduled debates, one on September 26 and the other October 9, would have to compete for viewers with National Football League games, referencing the similar complaints made regarding the dates with low expected ratings during the Democratic Party presidential debates.[372]

There were also debates between independent candidates.

| No. | Date | Time | Host | City | Moderator(s) | Participants | Viewership

(millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | September 26, 2016 | 9:00 p.m. EDT | Hofstra University | Hempstead, New York | Lester Holt | Donald Trump Hillary Clinton |

84.0[373] |

| VP | October 4, 2016 | 9:00 p.m. EDT | Longwood University | Farmville, Virginia | Elaine Quijano | Mike Pence Tim Kaine |

37.0[373] |

| P2 | October 9, 2016 | 8:00 p.m. CDT | Washington University in St. Louis | St. Louis, Missouri | Anderson Cooper Martha Raddatz |

Donald Trump Hillary Clinton |

66.5[373] |

| P3 | October 19, 2016 | 6:00 p.m. PDT | University of Nevada, Las Vegas | Las Vegas, Nevada | Chris Wallace | Donald Trump Hillary Clinton |

71.6[373] |

Timeline

Results

Election night and the next day

The news media and election experts were surprised at Trump's winning of the Electoral College. On the eve of the vote, spread betting firm Spreadex had Clinton at an Electoral College spread of 307–322 against Trump's 216–231.[374] The final polls showed a lead by Clinton, and in the end she did receive more votes.[375] Trump himself expected, based on polling, to lose the election, and rented a small hotel ballroom to make a brief concession speech, later remarking: "I said if we're going to lose I don't want a big ballroom."[376] Trump performed surprisingly well in all battleground states, especially Florida, Iowa, Ohio, and North Carolina. Even the Democratic-leaning Rust Belt states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin were narrowly won by Trump.[377]

According to the authors of Shattered: Inside Hillary Clinton's Doomed Campaign, the White House had concluded by late Tuesday night that Trump would win the election. Obama's political director David Simas called Clinton campaign manager Robby Mook to persuade Clinton to concede the election, with no success. Obama then called Clinton directly, citing the importance of continuity of government, to ask her to publicly acknowledge that Trump had won.[378] Believing that Clinton was still unwilling to concede, the president then called her campaign chair John Podesta, but the call to Clinton had likely already persuaded her.[379]

The Associated Press called Pennsylvania for Trump at 1:35 AM EST, putting Trump at 267 electoral votes. By 2:01 AM EST, they had called both Maine and Nebraska's second congressional districts for Trump, putting him at 269 electoral votes, making it impossible for Clinton to reach 270. One minute after this, John Podesta told Hillary Clinton's victory party in New York that the election was too close to call. At 2:29 AM EST, the Associated Press called Wisconsin, and the election, for Trump, giving him 279 electoral votes. By 2:37 AM EST, Clinton had called Trump to concede the election.[380][381]

On Wednesday morning at 2:30 AM EST, it was reported that Trump had secured Wisconsin's 10 electoral votes, giving him a majority of the 538 electors in the Electoral College, enough to make him the president-elect of the United States,[382] and Trump gave his victory speech at 2:50 AM EST.[382] Later that day, Clinton asked her supporters to accept the result and hoped that Trump would be "a successful president for all Americans."[383] In his speech, Trump appealed for unity, saying "it is time for us to come together as one united people", and praised Clinton as someone who was owed "a major debt of gratitude for her service to our country."[384]

Statistical analysis

The 2016 election was the fifth and most recent presidential election in which the winning candidate lost the popular vote.[2][4] Six states plus a portion of Maine that Obama won in 2012 switched to Trump (Electoral College votes in parentheses): Florida (29), Pennsylvania (20), Ohio (18), Michigan (16), Wisconsin (10), Iowa (6), and Maine's second congressional district (1). Initially, Trump won exactly 100 more Electoral College votes than Mitt Romney had in 2012, with two lost to faithless electors in the final tally. Thirty-nine states swung more Republican compared to the previous presidential election, while eleven states and the District of Columbia swung more Democratic.[245] Based on United States Census Bureau estimates of the voting age population (VAP), turnout of voters casting a vote for president was nearly 1% higher than in 2012. Examining overall turnout in the 2016 election, the University of Florida's Michael McDonald estimated that 138.8 million Americans cast a ballot. Considering a VAP of 250.6 million people and a voting-eligible population (VEP) of 230.6 million people, this is a turnout rate of 55.4% VAP and 60.2% VEP.[385] Based on this estimate, voter turnout was up compared to 2012 (54.1% VAP) but down compared to 2008 (57.4% VAP). An FEC report of the election recorded an official total of 136.7 million votes cast for president—more than any prior election.[1]

By losing New York, Trump became the fourth and most recent victorious candidate to lose his home state, which also occurred in 1844, 1916, and 1968. Furthermore, along with James Polk in 1844, Trump is one of two victorious presidential nominees to win without either their home state or birth state (in this case, both were New York). Data scientist Hamdan Azhar noted the paradoxes of the 2016 outcome, saying that "chief among them [was] the discrepancy between the popular vote, which Hillary Clinton won by 2.8 million votes, and the electoral college, where Trump won 304–227." He said Trump outperformed Mitt Romney's 2012 results, while Clinton only just matched Barack Obama's 2012 totals. Hamdan also said Trump was "the highest vote earner of any Republican candidate ever", exceeding George W. Bush's 62.04 million votes in 2004, though neither reached Clinton's 65.9 million, nor Obama's 69.5 million votes in 2008. He concluded, with help from The Cook Political Report, that the election hinged not on Clinton's large 2.8 million overall vote margin over Trump, but rather on about 78,000 votes from only three counties in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Michigan.[386] Clinton was the first former Secretary of State to be nominated by a major political party since James G. Blaine in 1884.

This is the first election since 1988 in which the Republican nominee won the states of Michigan and Pennsylvania, and the first since 1984 in which they won Wisconsin. It was the first time since 1988 that the Republicans won Maine's second congressional district and the first time since George W. Bush's victory in New Hampshire in 2000 that they won any electoral votes in the Northeast. This marked the first time that Maine split its electoral votes since it began awarding them based on congressional districts in 1972, and the first time the state split its electoral vote since 1828. The 2016 election marked the eighth consecutive presidential election where the victorious major party nominee did not receive a popular vote majority by a double-digit margin over the losing major party nominee(s), with the sequence of presidential elections from 1988 through 2016 surpassing the sequence from 1876 through 1900 to become the longest sequence of such presidential elections in U.S. history.[387][388] It was also the sixth presidential election in which both major party candidates were registered in the same home state; the others have been in 1860, 1904, 1920, 1940, and 1944. It was also the first election since 1928 that the Republicans won without having either Richard Nixon or one of the Bushes on the ticket.

Trump was the first president with neither prior public service nor military experience. This election was the first since 1908 where neither candidate was currently serving in public office. This was the first election since 1980 where a Republican was elected without carrying every former Confederate state in the process, as Trump lost Virginia in this election.[b] Trump became the first Republican to earn more than 300 electoral votes since the 1988 election, and the first Republican to win a Northeastern state since George W. Bush won New Hampshire in 2000. This was the first time since 1976 that a Republican presidential candidate lost a pledged vote via a faithless elector, and, additionally, this was the first time since 1972 that the winning presidential candidate lost an electoral vote due to faithless electors. With ballot access to the entire national electorate, Johnson received nearly 4.5 million votes (3.27%), the highest nationwide vote share for a third-party candidate since Ross Perot in 1996, while Stein received almost 1.45 million votes (1.06%), the most for a Green nominee since Ralph Nader in 2000. Johnson received the highest ever share of the vote for a Libertarian nominee, surpassing Ed Clark's 1980 result.[389]

Independent candidate Evan McMullin, who appeared on the ballot in eleven states, received over 732,000 votes (0.53%). He won 21.4% of the vote in his home state of Utah, the highest share of the vote for a third-party candidate in any state since 1992. Despite dropping out of the election following his defeat in the Democratic primary, Senator Bernie Sanders received 5.7% of the vote in his home state of Vermont, the highest write-in draft campaign percentage for a presidential candidate in American history. Johnson and McMullin were the first third-party candidates since Nader to receive at least 5% of the vote in one or more states, with Johnson crossing the mark in nine states and McMullin crossing it in two.[389] Trump became the oldest non-incumbent candidate elected president, besting Ronald Reagan in 1980, although this would be surpassed by Joe Biden in the next election. Of the 3,153 counties/districts/independent cities making returns, Trump won the most popular votes in 2,649 (84.02%) while Clinton carried 504 (15.98%).[390]

Electoral results

Notes:

- ^ a b In state-by-state tallies, Trump earned 306 pledged electors, Clinton 232. They lost respectively two and five votes to faithless electors. Vice presidential candidates Pence and Kaine lost one and five votes, respectively. Three other votes by electors were invalidated and recast.

- ^ In 1980, Democrat Jimmy Carter carried his home state of Georgia, despite losing the election.

- ^ Pence received 305 electoral votes for vice president, but only 304 as part of the Trump–Pence ticket; one faithless elector from Texas voted for Ron Paul as president instead of Trump, and is recorded separately below.[1]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Received electoral vote(s) from a faithless elector

- ^ a b c d e f g h Candidate received votes as a write-in. The exact numbers of write-in votes have been published for three states: California, New Hampshire, and Vermont.[392]

- ^ a b c Two faithless electors from Texas cast their presidential votes for Ron Paul and John Kasich, respectively. Chris Suprun said he cast his presidential vote for John Kasich and his vice presidential vote for Carly Fiorina. The other faithless elector in Texas, Bill Greene, cast his presidential vote for Ron Paul but cast his vice presidential vote for Mike Pence, as pledged. John Kasich received recorded write-in votes in Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Vermont.

| 232 | 306 |

| Clinton | Trump |

Results by state

The table below displays the official vote tallies by each state's Electoral College voting method. The source for the results of all states is the official Federal Election Commission report.[2] The column labeled "Margin" shows Trump's margin of victory over Clinton (the margin is negative for every state that Clinton won). A total of 29 third party and independent presidential candidates appeared on the ballot in at least one state. Former Governor of New Mexico Gary Johnson and physician Jill Stein repeated their 2012 roles as the nominees for the Libertarian Party and the Green Party, respectively.[393]

Aside from Florida and North Carolina, the states that secured Trump's victory are situated in the Great Lakes/Rust Belt region. Wisconsin went Republican for the first time since 1984, while Pennsylvania and Michigan went Republican for the first time since 1988.[394][395][396] Stein petitioned for a recount in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. The Clinton campaign pledged to participate in the Green Party recount efforts, while Trump backers challenged them in court.[397][398][399] Meanwhile, American Delta Party/Reform Party presidential candidate Rocky De La Fuente petitioned for and was granted a partial recount in Nevada.[400] According to a 2021 study in Science Advances, conversion of voters who voted for Obama in 2012 to Trump in 2016 contributed to Republican flips in Ohio, Michigan, and Pennsylvania.[401]

| States/districts won by Clinton/Kaine | |

| States/districts won by Trump/Pence | |

| † | At-large results (for states that split electoral votes) |

State or

district |

Hillary Clinton Democratic |

Donald Trump Republican |

Gary Johnson Libertarian |

Jill Stein Green |

Evan McMullin Independent |

Others | Margin | Total votes |

Sources

| |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | EV

|

Votes | % | EV

|

Votes | % | EV

|

Votes | % | EV

|

Votes | % | EV

|

Votes | % | EV

|

Votes | % | |||

| Alabama | 729,547 | 34.36% | – | 1,318,255 | 62.08% | 9 | 44,467 | 2.09% | – | 9,391 | 0.44% | – | – | – | – | 21,712 | 1.02% | – | 588,708 | 27.73% | 2,123,372 | [402] |

| Alaska | 116,454 | 36.55% | – | 163,387 | 51.28% | 3 | 18,725 | 5.88% | – | 5,735 | 1.80% | – | – | – | – | 14,307 | 4.49% | – | 46,933 | 14.73% | 318,608 | [403] |

| Arizona | 1,161,167 | 44.58% | – | 1,252,401 | 48.08% | 11 | 106,327 | 4.08% | – | 34,345 | 1.32% | – | 17,449 | 0.67% | – | 32,968 | 1.27% | – | 91,234 | 3.50% | 2,604,657 | [404] |

| Arkansas | 380,494 | 33.65% | – | 684,872 | 60.57% | 6 | 29,949 | 2.64% | – | 9,473 | 0.84% | – | 13,176 | 1.17% | – | 12,712 | 1.12% | – | 304,378 | 26.92% | 1,130,676 | [405] |

| California | 8,753,788 | 61.73% | 55 | 4,483,810 | 31.62% | – | 478,500 | 3.37% | – | 278,657 | 1.96% | – | 39,596 | 0.28% | – | 147,244 | 1.04% | – | −4,269,978 | −30.11% | 14,181,595 | [406] |

| Colorado | 1,338,870 | 48.16% | 9 | 1,202,484 | 43.25% | – | 144,121 | 5.18% | – | 38,437 | 1.38% | – | 28,917 | 1.04% | – | 27,418 | 0.99% | – | −136,386 | −4.91% | 2,780,247 | [407] |

| Connecticut | 897,572 | 54.57% | 7 | 673,215 | 40.93% | – | 48,676 | 2.96% | – | 22,841 | 1.39% | – | 2,108 | 0.13% | – | 508 | 0.03% | – | −224,357 | −13.64% | 1,644,920 | [408] |

| Delaware | 235,603 | 53.09% | 3 | 185,127 | 41.72% | – | 14,757 | 3.32% | – | 6,103 | 1.37% | – | 706 | 0.16% | – | 1,518 | 0.34% | – | −50,476 | −11.37% | 443,814 | [409][410] |

| District of Columbia | 282,830 | 90.86% | 3 | 12,723 | 4.09% | – | 4,906 | 1.57% | – | 4,258 | 1.36% | – | – | – | – | 6,551 | 2.52% | – | −270,107 | −86.77% | 311,268 | [411] |

| Florida | 4,504,975 | 47.82% | – | 4,617,886 | 49.02% | 29 | 207,043 | 2.20% | – | 64,399 | 0.68% | – | – | – | – | 25,736 | 0.28% | – | 112,911 | 1.20% | 9,420,039 | [412] |

| Georgia | 1,877,963 | 45.64% | – | 2,089,104 | 50.77% | 16 | 125,306 | 3.05% | – | 7,674 | 0.19% | – | 13,017 | 0.32% | – | 1,668 | 0.04% | – | 211,141 | 5.13% | 4,114,732 | [413][414] |

| Hawaii | 266,891 | 62.22% | 3 | 128,847 | 30.03% | – | 15,954 | 3.72% | – | 12,737 | 2.97% | – | – | – | – | 4,508 | 1.05% | 1 | −138,044 | −32.18% | 428,937 | [415] |

| Idaho | 189,765 | 27.49% | – | 409,055 | 59.26% | 4 | 28,331 | 4.10% | – | 8,496 | 1.23% | – | 46,476 | 6.73% | – | 8,132 | 1.18% | – | 219,290 | 31.77% | 690,255 | [416] |

| Illinois | 3,090,729 | 55.83% | 20 | 2,146,015 | 38.76% | – | 209,596 | 3.79% | – | 76,802 | 1.39% | – | 11,655 | 0.21% | – | 1,627 | 0.03% | – | −944,714 | −17.06% | 5,536,424 | [417] |

| Indiana | 1,033,126 | 37.77% | – | 1,557,286 | 56.94% | 11 | 133,993 | 4.90% | – | 7,841 | 0.29% | – | – | – | – | 2,712 | 0.10% | – | 524,160 | 19.17% | 2,734,958 | [418] |

| Iowa | 653,669 | 41.74% | – | 800,983 | 51.15% | 6 | 59,186 | 3.78% | – | 11,479 | 0.73% | – | 12,366 | 0.79% | – | 28,348 | 1.81% | – | 147,314 | 9.41% | 1,566,031 | [419] |

| Kansas | 427,005 | 36.05% | – | 671,018 | 56.65% | 6 | 55,406 | 4.68% | – | 23,506 | 1.98% | – | 6,520 | 0.55% | – | 947 | 0.08% | – | 244,013 | 20.60% | 1,184,402 | [420] |

| Kentucky | 628,854 | 32.68% | – | 1,202,971 | 62.52% | 8 | 53,752 | 2.79% | – | 13,913 | 0.72% | – | 22,780 | 1.18% | – | 1,879 | 0.10% | – | 574,177 | 29.84% | 1,924,149 | [421] |

| Louisiana | 780,154 | 38.45% | – | 1,178,638 | 58.09% | 8 | 37,978 | 1.87% | – | 14,031 | 0.69% | – | 8,547 | 0.42% | – | 9,684 | 0.48% | – | 398,484 | 19.64% | 2,029,032 | [422] |

| Maine † | 357,735 | 47.83% | 2 | 335,593 | 44.87% | – | 38,105 | 5.09% | – | 14,251 | 1.91% | – | 1,887 | 0.25% | – | 356 | 0.05% | – | −22,142 | −2.96% | 747,927 | [423][424] |

| ME-1 | 212,774 | 53.96% | 1 | 154,384 | 39.15% | – | 18,592 | 4.71% | – | 7,563 | 1.92% | – | 807 | 0.20% | – | 209 | 0.05% | – | −58,390 | −14.81% | 394,329 | |

| ME-2 | 144,817 | 40.98% | – | 181,177 | 51.26% | 1 | 19,510 | 5.52% | – | 6,685 | 1.89% | – | 1,080 | 0.31% | – | 147 | 0.04% | – | 36,360 | 10.29% | 353,416 | |

| Maryland | 1,677,928 | 60.33% | 10 | 943,169 | 33.91% | – | 79,605 | 2.86% | – | 35,945 | 1.29% | – | 9,630 | 0.35% | – | 35,169 | 1.26% | – | −734,759 | −26.42% | 2,781,446 | [425] |