Moschops

| Moschops Temporal range: Capitanian,

| |

|---|---|

| |

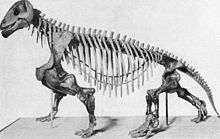

| Mounted skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Dinocephalia |

| Family: | †Tapinocephalidae |

| Subtribe: | †Moschopina |

| Genus: | †Moschops Broom, 1911 |

| Type species | |

| †Moschops capensis Broom, 1911

| |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Moschops (Greek for "calf face") is an extinct genus of therapsids that lived in the Guadalupian epoch, around 265–260 million years ago. They were heavily built plant eaters, and they may have lived partly in water, as hippopotamuses do. They had short, thick heads and might have competed by head-butting each other. Their elbow joints allowed them to walk with a more mammal-like gait rather than crawling. Their remains were found in the Karoo region of South Africa, belonging to the Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone. Therapsids, such as Moschops, are synapsids, the dominant land animals in the Permian period, which ended 252 million years ago.

Description

[edit]

Moschops were heavy set dinocephalian synapsids, measuring 2.7 metres (8.9 ft) in length,[1] and weighing 129 kg (284 lb) on average and 327.4 kg (722 lb) in maximum body mass.[2] They had small heads with broad orbits and heavily built short necks. Like other members of Tapinocephalidae, the skull had a tiny opening for the pineal organ.[3] The occiput was broad and deep, but the skull was more narrow in the dorsal border. Furthermore, the pterygoid arches and the angular region of the jaw with heavily built jaw muscles. Due to that and the possession of long-crowned, stout teeth, it is believed that Moschops was a herbivore feeding on nutrient-poor and tough vegetation, like cycad stems. Due to the presumably nutrient-poor food, it is likely they had to feed for long periods of time. The anatomy of the taxa allowed them to open the elbow joints more widely, enabling them to move in a more mammal-like posture than some other animals at the time. This helped to carry their massive bodies more easily while feeding, as well as allowing them short bursts of speed.[1][4] It has also been proposed that Moschops were possibly sub-aquatic.[1] Moschops had rather thick skulls, prompting speculation that individuals could have competed with one another by head-butting.[5] A 2017 published study would later confirm this by synchrotron scanning a Moschops capensis skull, which revealed numerous anatomical adaptations to the central nervous system for combative behaviour.[2] They were likely preyed upon by titanosuchids and larger therocephalian species.[4]

Earliest finds

[edit]Moschops material was first discovered in the Ecca Group (part of the Karoo Supergroup) of South Africa by Robert Broom. As the geological horizon was dubious, it was referred to have originated from the Ecca Group on the basis of Pareiasaurus remains in near proximity. The discovered material includes a holotype (AMNH 5550) and seven topotypes (AMNH 5551-5557). The degree of pachyostosis varies within the skulls of the specimens, and Broom believed this to have been linked to variations in gender and age. In 1910, the material was sent to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and described in 1911.[1]

Classification

[edit]

Moschops is characterized by a strongly pachyostosed skull with a broad intertemporal region and greatly reduced temporal fossae. Two species are known from the fossil record, M. capensis and M. koupensis. Two other species were assigned (M. whaitsi and M. oweni), but their validity is considered possibly dubious. [citation needed] Genera regarded as synonyms are Moschoides, Agnosaurus, Moschognathus and Pnigalion. Delphinognathus conocephalus could represent juvenile Moschops, thus possibly synonymous. Delphinognathus is only known from a single, moderately pachyostosed skull.[citation needed] It has a conical boss on the parietal surrounding the pineal foramen.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d William, Gregory (1926). "The skeleton of Moschops capensis, a dinocephalian reptile from the Permian of South Africa". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 56 (3): 179–251. hdl:2246/1323.

- ^ a b Benoit, Julien; Manger, Paul R.; Norton, Luke; Fernandez, Vincent; and Rubidge, Bruce S. (2017). "Synchrotron scanning reveals the palaeoneurology of the head-butting Moschops capensis (Therapsida, Dinocephalia)". PeerJ. 5: e3496. doi:10.7717/peerj.3496. PMC 5554600. PMID 28828230. S2CID 8019159.

- ^ The Age of Reptiles

- ^ a b Haughton, S. H. (1919). "A Review of the Reptilian Fauna of the Karroo System of South Africa". Transactions of the Geological Society of South Africa. 22: 14.

- ^ Barghusen, Herbert R. (1975). "A Review of Fighting Adaptations in Dinocephalians (Reptilia, Therapsida)". Paleobiology. 1 (3): 295–311. doi:10.1017/s0094837300002542. JSTOR 2400370. S2CID 87163815.

- ^ Boonstra, L. D. (1969). "The fauna of the Tapinocephalus zone (Beaufort beds of the Karoo)". Annals of the South African Museum. 56 (1). Cape Town: 42.

External links

[edit]- Moschops, pictures and a brief overview

- Tapinocephalidae at Paleos.com