Pleasantville (film)

| Pleasantville | |

|---|---|

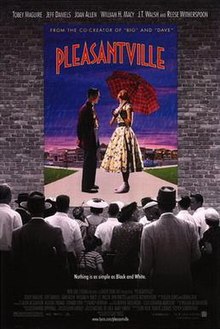

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Gary Ross |

| Written by | Gary Ross |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | John Lindley |

| Edited by | William Goldenberg |

| Music by | Randy Newman |

Production company | Larger Than Life Productions |

| Distributed by | New Line Cinema |

Release date |

|

Running time | 124 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $60 million[1] |

| Box office | $49.8 million |

Pleasantville is a 1998 American teen fantasy comedy-drama film written, co-produced, and directed by Gary Ross (in his directorial debut). It stars Tobey Maguire, Jeff Daniels, Joan Allen, William H. Macy, J. T. Walsh, and Reese Witherspoon, with Don Knotts, Paul Walker, Marley Shelton, and Jane Kaczmarek in supporting roles. The story centers on two siblings who wind up trapped in a 1950s TV show, set in a small Midwest town, where residents are seemingly perfect.

The film was one of J. T. Walsh's final performances and was dedicated to his memory. It was also the final on-screen film appearance of Don Knotts, who would subsequently take on voice acting roles until his death.

Plot

[edit]In 1998, while their mother is away, high school-aged twin siblings David and Jennifer fight over the television, breaking the remote control. A mysterious TV repairman suddenly arrives and, impressed by David's knowledge and love of Pleasantville, a black-and-white 1950s sitcom about the idyllic Parker family, gives him an unusual remote control before departing. When they use it, David and Jennifer are transported into the Parkers' house, in Pleasantville's black-and-white world. George and Betty Parker believe them to be their children, Bud and Mary Sue. Communicating through the Parkers' television, David tries to reason with the repairman, who is offended that they want to come home, thinking they should be lucky to live in Pleasantville.

There, fire is impossible to start (firefighters merely rescue cats from trees), and everyone is unaware that anything exists outside of Pleasantville, as all roads circle back into it. David tells Jennifer they must play the show's characters and not disrupt Pleasantville, but she rebelliously goes on a date with Mary Sue's boyfriend, Skip Martin, the most popular boy in school. She has sex with Skip, who is shocked by the experience, which leads to the first bursts of color appearing in town.

Bill Johnson, owner of the malt shop where Bud works, experiences an existential crisis after realizing the repetitive nature of his life. David tries to help him break out of his routine and notices an attraction between Bill and Betty.

As Jennifer influences other teenagers, parts of Pleasantville become colorized, including some of the residents. Books in the library, previously blank, begin to fill with words after David and Jennifer summarize the plot to their classmates. When Jennifer gives a curious Betty an explanation about sex and tells her how to masturbate, Betty has an orgasm that results in her colorization and a fire in a tree outside.

Other foreign concepts, such as rain, begin to appear. David shows Bill a book of modern art, which inspires him to begin painting and to pursue a romance with Betty. Jennifer loses interest in sex and partying and becomes colorized after finding passion in literature. David pursues a romance with Margaret but is confused and disappointed to find he is still black and white.

Betty leaves George to be with Bill, bewildering him. The town leaders, including the mayor, Big Bob, and others who remain black and white are suspicious of all of these changes and begin to discriminate against the "colored" people, considering them a threat to Pleasantville's values.

A riot is ignited by Bill's nude painting of Betty on the window of his malt shop. The shop is destroyed, books are burned and colored people are harassed in the street. David defends Betty from a gang of teenage boys. Punching one of them, David scares the rest away, demonstrating newfound courage that turns him colored.

The town council bans colored citizens from public venues, closes Lover's Lane, outlaws reading, rock music and using colorful paint. In protest, David and Bill paint a colorful mural outside the soda fountain depicting the beauty of love, sex, rain, music and literature. They are arrested and brought to trial in front of the entire town. David confronts George about losing Betty, persuading him to admit he does not just miss the cooking and the cleaning. George becomes colorized and the rest of the town, except for Big Bob, become colorized as well. When David drives him to fury over the suggestion that one day there could be a world where women go off to work and men stay home and cook, Big Bob becomes colored and flees in shame.

The town celebrates their victory, and color televisions start being sold. They broadcast new programs and footage of other countries. The town's roads also start leading to other cities. With Pleasantville changed, Jennifer chooses to continue her new life in the TV world. Bidding farewell to her, Margaret and Betty, David uses the remote control to return to the real world, where only an hour has passed since his disappearance. He comforts his mother, who had left to meet a man only to get cold feet, and assures her that nothing has to be perfect. In Pleasantville, citizens enjoy their lives, and Jennifer attends college.

Cast

[edit]- Tobey Maguire as David / Bud Parker

- Kevin Connors as the real Bud Parker

- Reese Witherspoon as Jennifer / Mary Sue Parker

- Natalie Ramsey as the real Mary Sue Parker

- Jeff Daniels as Bill Johnson, owner of the malt shop, David/Bud's boss

- Joan Allen as Betty Parker, Bud and Mary Sue's mother

- William H. Macy as George Parker, Bud and Mary Sue's father

- J. T. Walsh as Bob "Big Bob", mayor of Pleasantville

- Paul Walker as Skip Martin, captain of Pleasantville High's basketball team, Jennifer/Mary Sue's boyfriend

- Marley Shelton as Margaret Henderson, a pretty and popular Pleasantville High cheerleader, David/Bud's girlfriend

- Giuseppe Andrews as Howard, David's best friend in the real world

- Jenny Lewis as Christin, one of Jennifer's friends in the real world

- Marissa Ribisi as Kimmy, one of Jennifer's friends in the real world

- Jane Kaczmarek as David and Jennifer's mother

- Don Knotts as TV Repairman

- Denise Dowse as Health Teacher

- David Tom as "Whitey"

- Maggie Lawson as Lisa Anne, one of Mary Sue's best friends

- Andrea Taylor as Peggy Jane, one of Mary Sue's best friends

Production

[edit]This was the first time that a new feature film was created by scanning and digitizing recorded film footage for the purpose of removing or manipulating colors. The black-and-white-meets-color world portrayed in the movie was filmed entirely in color; in all, approximately 163,000 frames of 35 mm footage were scanned, in order to selectively desaturate and adjust contrast digitally. The scanning was done in Los Angeles by Cinesite, utilizing a Spirit DataCine for scanning at 2K resolution[2] and a MegaDef Colour Correction System from Pandora International. Principal photography took place from March 1 to July 2, 1997.

The death of camera operator Brent Hershman, who fell asleep driving home after a 19-hour workday on the set of the film, resulted in a wrongful death suit, claiming that New Line Cinema, New Line Productions and Juno Pix Inc. were responsible for the death as a result of the lengthy work hours imposed on the set.[3][4] In response to Hershman's death, crew members launched a petition for 'Brent’s Rule', which would limit workdays to a maximum of 14 hours; the petition was ultimately unsuccessful.[5][6]

The film is dedicated to Hershman, as well as to director Ross's mother, Gail, and actor J. T. Walsh, who also died before the film's release.[7]

Shortly before and during the film's release, an online contest was held to visit the real Pleasantville, Iowa.[8] Over 30,000 people entered. The winner, who remained anonymous, declined the trip and opted to receive the $10,000 cash prize instead.

Themes

[edit]Director Gary Ross stated, "This movie is about the fact that personal repression gives rise to larger political oppression...That when we're afraid of certain things in ourselves or we're afraid of change, we project those fears on to other things, and a lot of very ugly social situations can develop."[9]

Robert Beuka says in his book SuburbiaNation, "Pleasantville is a morality tale concerning the values of contemporary suburban America by holding that social landscape up against both the Utopian and the dystopian visions of suburbia that emerged in the 1950s."[10]

Robert McDaniel of Film & History described the town as the perfect place, "It never rains, the highs and lows rest at 72 degrees, the fire department exists only to rescue treed cats, and the basketball team never misses the hoop." However, McDaniel says, "Pleasantville is a false hope. David's journey tells him only that there is no 'right' life, no model for how things are 'supposed to be'."[11]

Warren Epstein of The Gazette wrote, "This use of color as a metaphor in black-and-white films certainly has a rich tradition, from the over-the-rainbow land in The Wizard of Oz to the girl in the red dress who made the Holocaust real for Oskar Schindler in Schindler's List. In Pleasantville, color represents the transformation from repression to enlightenment. People—and their surroundings—change from black-and-white to color when they connect with the essence of who they really are."[12]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Pleasantville earned $8.9 million during its opening weekend. It would ultimately earn a total of $40.8 million against a $60 million budget making it a box office flop, despite the critical success.[13]

Critical reception

[edit]Pleasantville received positive reviews from critics. Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes gave the film an 86% rating from 97 reviews, an average rating of 7.7/10, with the critical consensus: "Filled with lighthearted humor, timely social commentary, and dazzling visuals, Pleasantville is an artful blend of subversive satire and well-executed Hollywood formula."[14] Metacritic assigned a score of 71 based on 32 reviews.[15] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B" on an A+ to F scale.[16]

Roger Ebert gave the film four out of four, calling it "one of the best and most original films of the year".[17] Janet Maslin wrote that its "ingenious fantasy" has "seriously belabored its once-gentle metaphor and light comic spirit".[18] Peter M. Nichols, judging the film for its child-viewing worthiness, jokingly wrote in The New York Times that the town of Pleasantville "makes Father Knows Best look like Dallas".[19] Joe Leydon of Variety called it "a provocative, complex and surprisingly anti-nostalgic parable wrapped in the beguiling guise of a commercial high-concept comedy". He commented that some storytelling problems emerge late in the film, but wrote that "Ross is to be commended for refusing to take the easy way out".[20]

Entertainment Weekly wrote a mixed review: "Pleasantville is ultramodern and beautiful. But technical elegance and fine performances mask the shallowness of a story as simpleminded as the '50s TV to which it condescends; certainly it's got none of the depth, poignance, and brilliance of The Truman Show, the recent TV-is-stifling drama that immediately comes to mind."[21] Dave Rettig of Christian Answers said: "On a surface level, the message of the film appears to be 'morality is black and white and pleasant, but sin is color and better,' because often through the film the Pleasantvillians become color after sin (adultery, premarital sex, physical assault, etc...). In one scene in particular, a young woman shows a brightly colored apple to young (and not yet colored) David, encouraging him to take and eat it. Very reminiscent of the Genesis's account of the fall of man."[22]

Time Out New York reviewer Andrew Johnston observed, "Pleasantville doesn't have the consistent internal logic that great fantasies require, and Ross just can't resist spelling everything out for the dim bulbs in the audience. That's a real drag, because the film's fundamental premise—crossing America's nostalgia fixation with Pirandello and the Oz/Narnia/Wonderland archetype—is so damn cool, the film really should have been a masterpiece."[23]

Jesse Walker, writing a retrospective in the January 2010 issue of Reason, argued that the film was misunderstood as a tale of kids from the 1990s bringing life into the conformist world of the 1950s. Walker points out that the supposedly outside influences changing the town of Pleasantville—the civil rights movement, J. D. Salinger, modern art, premarital sex, cool jazz and rockabilly—were all present in the 1950s. Pleasantville "contrasts the faux '50s of our TV-fueled nostalgia with the social ferment that was actually taking place while those sanitized shows first aired".[24]

Filmmaker Jon M. Chu cited the film, alongside The Truman Show (also released in 1998), as an influence on how the Land of Oz is thematically portrayed in the two-part film adaptation of the musical Wicked (2024-2025), saying "It helps create this idea of the rebelliousness that this new younger generation are discovering ... How far will that take everybody in Oz throughout the course of the whole story of both movies? It's an awakening of a generation. You start to see the truth about things that maybe you were taught differently."[25]

Accolades

[edit]| Award | Category | Recipient(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[26] | Best Art Direction | Jeannine Oppewall and Jay Hart | Nominated |

| Best Costume Design | Judianna Makovsky | Nominated | |

| Best Original Dramatic Score | Randy Newman | Nominated | |

| American Comedy Awards[27] | Funniest Supporting Actor in a Motion Picture | William H. Macy | Nominated |

| Art Directors Guild Awards[28] | Excellence in Production Design for a Feature Film | Jeannine Oppewall | Nominated |

| Artios Awards[29] | Best Casting for Feature Film – Drama | Ellen Lewis and Debra Zane | Nominated |

| Awards Circuit Community Awards | Best Actress in a Supporting Role | Joan Allen | Nominated |

| Best Art Direction | Jeannine Oppewall and Jay Hart | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | John Lindley | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Judianna Makovsky | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | Randy Newman | Nominated | |

| Best Visual Effects | Nominated | ||

| Best Cast Ensemble | Nominated | ||

| Boston Society of Film Critics Awards[30] | Best Supporting Actor | William H. Macy (also for A Civil Action and Psycho) | Won[a] |

| Best Supporting Actress | Joan Allen | Won | |

| Best Cinematography | John Lindley | Nominated | |

| Chicago Film Critics Association Awards[31] | Best Supporting Actress | Joan Allen | Nominated |

| Chlotrudis Awards[32] | Best Supporting Actress | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | John Lindley | Nominated | |

| Costume Designers Guild Awards[33] | Excellence in Costume Design for Film | Judianna Makovsky | Won |

| Critics' Choice Movie Awards[34] | Best Picture | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Joan Allen | Won[b] | |

| Dallas–Fort Worth Film Critics Association Awards | Best Supporting Actress | Won | |

| Hugo Awards | Best Dramatic Presentation | Gary Ross | Nominated |

| International Film Music Critics Association Awards[35] | Best Original Score for a Drama Film | Randy Newman | Nominated |

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards[36] | Best Supporting Actress | Joan Allen | Won |

| Best Production Design | Jeannine Oppewall | Won | |

| Online Film & Television Association Awards[37] | Best Comedy/Musical Picture | Jon Kilik, Gary Ross and Steven Soderbergh | Nominated |

| Best Comedy/Musical Actress | Joan Allen | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Nominated | ||

| Best First Feature | Gary Ross | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | John Lindley | Nominated | |

| Best Comedy/Musical Score | Randy Newman | Nominated | |

| Best Adapted Song | "Across the Universe" Music and Lyrics by John Lennon and Paul McCartney Performed by Fiona Apple |

Won | |

| Best Makeup | Nominated | ||

| Best Visual Effects | Nominated | ||

| Online Film Critics Society Awards[38] | Best Supporting Actress | Joan Allen | Won |

| Best Cinematography | John Lindley | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | William Goldenberg | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | Randy Newman | Won | |

| Producers Guild of America Awards[39] | Most Promising Producer in Theatrical Motion Pictures | Gary Ross | Won |

| Satellite Awards[40] | Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy | Nominated | |

| Best Actor in a Supporting Role in a Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy | Jeff Daniels | Nominated | |

| Best Actress in a Supporting Role in a Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy | Joan Allen | Won | |

| Best Director | Gary Ross | Nominated | |

| Best Original Screenplay | Won | ||

| Best Art Direction | Jeannine Oppewall and Jay Hart | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | John Lindley | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Judianna Makovsky | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | William Goldenberg | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | Randy Newman | Nominated | |

| Saturn Awards[41] | Best Fantasy Film | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Joan Allen | Won | |

| Best Performance by a Younger Actor/Actress | Tobey Maguire | Won | |

| Best Writing | Gary Ross | Nominated | |

| Best Costumes | Judianna Makovsky | Nominated | |

| Southeastern Film Critics Association Awards[42] | Best Picture | 7th Place | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Joan Allen | Won | |

| Teen Choice Awards[43] | Choice Movie – Drama | Nominated | |

| Most Funniest Scene | Reese Witherspoon and Joan Allen | Nominated | |

| Turkish Film Critics Association Awards | Best Foreign Film | 13th Place | |

| Young Hollywood Awards[44] | Female Breakthrough Performance | Reese Witherspoon | Won |

Soundtrack

[edit]| Pleasantville: Music from the Motion Picture | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Various | |

| Released | October 13, 1998 |

| Recorded | Various |

| Genre | Pop |

| Length | 47:37 |

| Label | New Line |

| Producer |

|

The soundtrack features music from the 1950s and 1960s such as "Be-Bop-A-Lula" by Gene Vincent, "Take Five" by The Dave Brubeck Quartet, "So What" by Miles Davis and "At Last" by Etta James. The main score was composed by Randy Newman; he received an Oscar nomination in the original music category. A score release is also in distribution, although the suite track is only available on the standard soundtrack. Among the Pleasantville DVD "Special Features" is a music-only feature with commentary by Randy Newman.

The music video for Fiona Apple's version of "Across the Universe", directed by Paul Thomas Anderson, uses the set of the diner from the film. AllMusic rated the album two-and-a-half stars out of five.[45]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Tied with Billy Bob Thornton for A Simple Plan.

- ^ Tied with Kathy Bates for Primary Colors.

References

[edit]- ^ "Pleasantville (1998)". Box Office Mojo.

- ^ Fisher, Bob (November 1998). "Black & white in color". American Cinematographer: 1. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015.

Watts suggested using the Philips Spirit DataCine at Cinesite Digital Imaging in Los Angeles for converting the film to data.

(full article link) - ^ Polone, Gavin (May 23, 2012). "Polone: The Unglamorous, Punishing Hours of Working on a Hollywood Set". Vulture. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ^ O'Neill, Ann W. (December 21, 1997). "Death After Long Workday Spurs Suit". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (March 22, 1997). "Crew Rallies for Shorter Days Following Colleague's Death". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ Busch, Anita (February 1, 2018). "Hollywood's Grueling Hours & Drowsy-Driving Problem: Crew Members Speak Out Despite Threat To Careers". Deadline.com. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ Bergeron, Michael (April 4, 2012). "Gary Ross Interview". Free Press Houston. Archived from the original on May 3, 2016. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ "20 fact you might not know about 'Pleasantville'". Yardbarker. November 11, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ Johnson-Ott, Edward (1998). "Pleasantville (1998)". NUVO Newsweekly. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ Beuka, Robert (2004). SuburbiaNation: Reading Suburban Landscape in Twentieth-Century American Fiction and Film (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9781403963673.

- ^ McDaniel, Robb (2002). "Pleasantville (Ross 1998)" (PDF). Film & History. 32 (1): 85–86. (link requires Project MUSS access)

- ^ Epstein, Warren. "True Colors - A Small Town Blossoms when '50s and '90s collide in Pleasantville". The Gazette (Colorado Springs).

- ^ Wolk, Josh (October 26, 1998). ""Pleasantville" tops the box office, but it's the only new wide release that scored". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ "Pleasantville (1998)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ "Pleasantville Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ "Home". CinemaScore. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 1, 1998). "Pleasantville (PG-13)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "New Video Releases". The New York Times. March 19, 1999. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ Nichols, Peter M. (November 6, 1998). "Taking the Children; Bobby-Soxers and Dinos Brought Back to Life". The New York Times. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ Leydon, Joe (September 17, 1998). "Review: 'Pleasantville'". Variety. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- ^ "Pleasantville (1998)". Entertainment Weekly. October 23, 1998. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ Rettig, Dave. "Pleasantville (1998)". Christian Answers. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ Johnston, Andrew (October 22, 1998). "Pleasantville". Time Out New York. p. 97.

- ^ Walker, Jesse (January 2010). "Beyond Pleasantville: Permissiveness wasn't born in the '60s". Reason. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ^ https://www.syfy.com/syfy-wire/wicked-how-oz-epic-channels-the-truman-show-pleasantville

- ^ "The 71st Academy Awards (1999) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ "Pleasantville | Le Cinema Paradiso Blu-Ray reviews and DVD reviews". lecinemaparadiso.co.uk. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "3rd Annual Excellence in Production Design Awards". Archived from the original on September 27, 2015. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ "Nominees/Winners". Casting Society of America. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ "BSFC Winners: 1990s". Boston Society of Film Critics. July 27, 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1988-2013 Award Winner Archives". Chicago Film Critics Association. January 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "1999, 5th Annual Awards". Chlotrudis Society for Independent Film. June 1, 2023. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "1st CDGA Details". Costume Designers Guild. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "The BFCA Critics' Choice Awards :: 1998". Broadcast Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on December 12, 2008.

- ^ "1998 FMCJ Awards". IFMCA. 1999. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ "The 24th Annual Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "3rd Annual Film Awards (1998)". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "1998 Awards (2nd Annual)". Online Film Critics Society. January 3, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ^ Madigan, Nick (March 3, 1999). "Producers tap 'Ryan'; Kelly, Hanks TV winners". Variety. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ "International Press Academy website – 1999 3rd Annual SATELLITE Awards". Archived from the original on February 1, 2008.

- ^ "Past Saturn Awards". Saturn Awards.org. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved May 7, 2008.

- ^ "1998 SEFA Awards". sefca.net. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "Funky Categories Set Teen Choice Awards Apart". Hartford Courant. August 12, 1999. Archived from the original on October 14, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ Sim, David (March 22, 2019). "Reese Witherspoon's Birthday: Her Best Movies". Newsweek. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ Pleasantville: Music from the Motion Picture at AllMusic

Further reading

[edit]- Millar, Jeff. "Pleasantville" (review). Houston Chronicle. October 23, 1998.

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- 1998 films

- 1990s teen comedy-drama films

- American black-and-white films

- American fantasy comedy-drama films

- American satirical films

- American teen comedy-drama films

- Fictional television shows

- Films about television

- Films directed by Gary Ross

- Films produced by Steven Soderbergh

- Films scored by Randy Newman

- Films set in the 1950s

- Films set in 1958

- Films set in the 1990s

- Films partially in color

- Films with screenplays by Gary Ross

- Films about prejudice

- New Line Cinema films

- 1998 directorial debut films

- Magic realism films

- Nostalgia in the United States

- Films produced by Jon Kilik

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s American films

- Postmodern films

- Saturn Award–winning films

- English-language fantasy comedy-drama films