Piston

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2013) |

A piston is a component of reciprocating engines, reciprocating pumps, gas compressors, hydraulic cylinders and pneumatic cylinders, among other similar mechanisms. It is the moving component that is contained by a cylinder and is made gas-tight by piston rings. In an engine, its purpose is to transfer force from expanding gas in the cylinder to the crankshaft via a piston rod and/or connecting rod. In a pump, the function is reversed and force is transferred from the crankshaft to the piston for the purpose of compressing or ejecting the fluid in the cylinder. In some engines, the piston also acts as a valve by covering and uncovering ports in the cylinder.

Piston engines

[edit]

Internal combustion engines

[edit]

An internal combustion engine is acted upon by the pressure of the expanding combustion gases in the combustion chamber space at the top of the cylinder. This force then acts downwards through the connecting rod and onto the crankshaft. The connecting rod is attached to the piston by a swivelling gudgeon pin (US: wrist pin). This pin is mounted within the piston: unlike the steam engine, there is no piston rod or crosshead (except big two stroke engines).

The typical piston design is on the picture. This type of piston is widely used in car diesel engines. According to purpose, supercharging level and working conditions of engines the shape and proportions can be changed.

High-power diesel engines work in difficult conditions. Maximum pressure in the combustion chamber can reach 20 MPa and the maximum temperature of some piston surfaces can exceed 450 °C. It is possible to improve piston cooling by creating a special cooling cavity. Injector supplies this cooling cavity «A» with oil through oil supply channel «B». For better temperature reduction construction should be carefully calculated and analysed. Oil flow in the cooling cavity should be not less than 80% of the oil flow through the injector.

The pin itself is of hardened steel and is fixed in the piston, but free to move in the connecting rod. A few designs use a 'fully floating' design that is loose in both components. All pins must be prevented from moving sideways and the ends of the pin digging into the cylinder wall, usually by circlips.

Gas sealing is achieved by the use of piston rings. These are a number of narrow iron rings, fitted loosely into grooves in the piston, just below the crown. The rings are split at a point in the rim, allowing them to press against the cylinder with a light spring pressure. Two types of ring are used: the upper rings have solid faces and provide gas sealing; lower rings have narrow edges and a U-shaped profile, to act as oil scrapers. There are many proprietary and detail design features associated with piston rings.

Pistons are usually cast or forged from aluminium alloys. For better strength and fatigue life, some racing pistons[1] may be forged instead. Billet pistons are also used in racing engines because they do not rely on the size and architecture of available forgings, allowing for last-minute design changes. Although not commonly visible to the naked eye, pistons themselves are designed with a certain level of ovality and profile taper, meaning they are not perfectly round, and their diameter is larger near the bottom of the skirt than at the crown.[2]

Early pistons were of cast iron, but there were obvious benefits for engine balancing if a lighter alloy could be used. To produce pistons that could survive engine combustion temperatures, it was necessary to develop new alloys such as Y alloy and Hiduminium, specifically for use as pistons.

A few early gas engines[i] had double-acting cylinders, but otherwise effectively all internal combustion engine pistons are single-acting. During World War II, the US submarine Pompano[ii] was fitted with a prototype of the infamously unreliable H.O.R. double-acting two-stroke diesel engine. Although compact, for use in a cramped submarine, this design of engine was not repeated.

![]() Media related to Internal combustion engine pistons at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Internal combustion engine pistons at Wikimedia Commons

Trunk pistons

[edit]Trunk pistons are long relative to their diameter. They act both as a piston and cylindrical crosshead. As the connecting rod is angled for much of its rotation, there is also a side force that reacts along the side of the piston against the cylinder wall. A longer piston helps to support this.

Trunk pistons have been a common design of piston since the early days of the reciprocating internal combustion engine. They were used for both petrol and diesel engines, although high speed engines have now adopted the lighter weight slipper piston.

A characteristic of most trunk pistons, particularly for diesel engines, is that they have a groove for an oil ring below the gudgeon pin, in addition to the rings between the gudgeon pin and crown.

The name 'trunk piston' derives from the 'trunk engine', an early design of marine steam engine. To make these more compact, they avoided the steam engine's usual piston rod with separate crosshead and were instead the first engine design to place the gudgeon pin directly within the piston. Otherwise these trunk engine pistons bore little resemblance to the trunk piston; they were extremely large diameter and double-acting. Their 'trunk' was a narrow cylinder mounted in the centre of the piston.

![]() Media related to Trunk pistons at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Trunk pistons at Wikimedia Commons

Crosshead pistons

[edit]Large slow-speed Diesel engines may require additional support for the side forces on the piston. These engines typically use crosshead pistons. The main piston has a large piston rod extending downwards from the piston to what is effectively a second smaller-diameter piston. The main piston is responsible for gas sealing and carries the piston rings. The smaller piston is purely a mechanical guide. It runs within a small cylinder as a trunk guide and also carries the gudgeon pin.

Lubrication of the crosshead has advantages over the trunk piston as its lubricating oil is not subject to the heat of combustion: the oil is not contaminated by combustion soot particles, it does not break down owing to the heat and a thinner, less viscous oil may be used. The friction of both piston and crosshead may be only half of that for a trunk piston.[3]

Because of the additional weight of these pistons, they are not used for high-speed engines.

![]() Media related to Crosshead pistons at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Crosshead pistons at Wikimedia Commons

Slipper pistons

[edit]

A slipper piston is a piston for a petrol engine that has been reduced in size and weight as much as possible. In the extreme case, they are reduced to the piston crown, support for the piston rings, and just enough of the piston skirt remaining to leave two lands so as to stop the piston rocking in the bore. The sides of the piston skirt around the gudgeon pin are reduced away from the cylinder wall. The purpose is mostly to reduce the reciprocating mass, thus making it easier to balance the engine and so permit high speeds.[4] In racing applications, slipper piston skirts can be configured to yield extremely light weight while maintaining the rigidity and strength of a full skirt.[5] Reduced inertia also improves mechanical efficiency of the engine: the forces required to accelerate and decelerate the reciprocating parts cause more piston friction with the cylinder wall than the fluid pressure on the piston head.[6] A secondary benefit may be some reduction in friction with the cylinder wall, since the area of the skirt, which slides up and down in the cylinder is reduced by half. However, most friction is due to the piston rings, which are the parts which actually fit the tightest in the bore and the bearing surfaces of the wrist pin, and thus the benefit is reduced.

![]() Media related to Slipper pistons at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Slipper pistons at Wikimedia Commons

Deflector pistons

[edit]

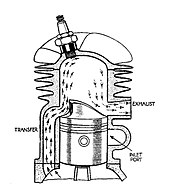

Deflector pistons are used in two-stroke engines with crankcase compression, where the gas flow within the cylinder must be carefully directed in order to provide efficient scavenging. With cross scavenging, the transfer (inlet to the cylinder) and exhaust ports are on directly facing sides of the cylinder wall. To prevent the incoming mixture passing straight across from one port to the other, the piston has a raised rib on its crown. This is intended to deflect the incoming mixture upwards, around the combustion chamber.[7]

Much effort, and many different designs of piston crown, went into developing improved scavenging. The crowns developed from a simple rib to a large asymmetric bulge, usually with a steep face on the inlet side and a gentle curve on the exhaust. Despite this, cross scavenging was never as effective as hoped. Most engines today use Schnuerle porting instead. This places a pair of transfer ports in the sides of the cylinder and encourages gas flow to rotate around a vertical axis, rather than a horizontal axis.[8]

![]() Media related to Deflector pistons at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Deflector pistons at Wikimedia Commons

Racing pistons

[edit]

In racing engines, piston strength and stiffness is typically much higher than that of a passenger car engine, while the weight is much less, to achieve the high engine RPM necessary in racing.[9]

Hydraulic cylinders

[edit]

Hydraulic cylinders can be both single-acting or double-acting. A hydraulic actuator controls the movement of the piston back and/or forth. Guide rings guides the piston and rod and absorb the radial forces that act perpendicularly to the cylinder and prevent contact between sliding the metal parts.

Steam engines

[edit]

Steam engines are usually double-acting (i.e. steam pressure acts alternately on each side of the piston) and the admission and release of steam is controlled by slide valves, piston valves or poppet valves. Consequently, steam engine pistons are nearly always comparatively thin discs: their diameter is several times their thickness. (One exception is the trunk engine piston, shaped more like those in a modern internal-combustion engine.) Another factor is that since almost all steam engines use crossheads to translate the force to the drive rod, there are few lateral forces acting to try and "rock" the piston, so a cylinder-shaped piston skirt isn't necessary.

Pumps

[edit]Piston pumps can be used to move liquids or compress gases.

For liquids

[edit]For gases

[edit]Air cannons

[edit]There are two special type of pistons used in air cannons: close tolerance pistons and double pistons. In close tolerance pistons O-rings serve as a valve, but O-rings are not used in double piston types.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Air gun

- Fire piston

- Fruit press

- Gas-operated reloading, using a gas piston

- Hydraulic cylinder

- List of auto parts

- Piston motion equations

- Shock absorber

- Slide whistle

- Steam locomotive components

- Syringe

- Wankel engine, an internal combustion engine design with a rotor instead of pistons

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Magda, Mike. "What Makes A Racing Piston?". Retrieved 2018-04-22.

- ^ Bailey, Kevin. "Full-Round vs. Strutted: Piston Forging Designs and Skirt Styles Explained". Retrieved 2018-07-15.

- ^ Ricardo (1922), p. 116.

- ^ Ricardo (1922), p. 149.

- ^ Piston with improved side loading resistance, 2009-10-12, retrieved 2018-04-22

- ^ Ricardo (1922), pp. 119–120, 122.

- ^ Irving, Two stroke power units, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Irving, Two stroke power units, pp. 15–16.

- ^ "Racing Piston Technology – Piston Weight And Design – Circle Track Magazine". Hot Rod Network. 2007-05-31. Retrieved 2018-04-22.

Bibliography

[edit]- Irving, P.E. (1967). Two-Stroke Power Units. Newnes.

- Ricardo, Harry (1922). The Internal Combustion Engine. Vol. I: Slow-Speed Engines (1st ed.). London: Blackie.