Pierre Le Gros the Younger

Pierre Le Gros | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Pierre Le Gros the Younger (anonymous drawing, early 18th century; unknown location) | |

| Born | 12 April 1666 Paris |

| Died | 3 May 1719 (aged 53) Rome |

| Resting place | San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Sculptor |

| Style | Baroque |

Pierre Le Gros (12 April 1666 Paris – 3 May 1719 Rome) was a French sculptor, active almost exclusively in Baroque Rome where he was the pre-eminent sculptor for nearly two decades.[1]: 18

He created monumental works of sculpture for the Jesuits and the Dominicans and found himself centre stage of the two most prestigious artistic campaigns of his era, the Altar of Saint Ignatius of Loyola in the Gesù and the cycle of the twelve huge Apostle statues in the nave of the Lateran basilica. Le Gros' handling of the marble attracted powerful patrons like the papal treasurer Lorenzo Corsini (much later to become Pope Clement XII) and Cardinal de Bouillon, as Dean of the Sacred College the highest ranking cardinal. He also played a prominent role in more intimate settings like the chapel of the Monte di Pietà and the Cappella Antamori in San Girolamo della Carità, both little treasures of the Roman late baroque not known to many because they are difficult to access.

Le Gros was the most exuberant baroque sculptor of all his contemporaries but eventually lost his long battle for artistic dominance to a prevailing classicist tendency against which he fought in vain.

Name and family

[edit]While he himself always signed as Le Gros and is referred to in this way in all legal documents,[1]: passim it has become common practice in the 19th and 20th centuries to spell the name Legros. Scholars frequently add a suffix like 'the Younger'[2] or 'Pierre II'[3] to distinguish him from his father, Pierre Le Gros the Elder, who was also a sculptor of renown to the French king Louis XIV.

Le Gros was born in Paris into a family with a strong artistic pedigree. Jeanne, his mother, died when he was three, but he stayed in close contact with her brothers, the sculptors Gaspard and Balthazard Marsy, whose workshop he frequented and eventually inherited at the age of fifteen.[4] His initial training as a sculptor lay in the hands of his father while he learned drawing from the engraver Jean Le Pautre,[1]: 10 the uncle of his stepmother, Marie Le Pautre.[note 1] His half brother Jean (1671–1745) was to become a portrait painter.[5]

Student

[edit]

As a student of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture Le Gros was awarded the prestigious Prix de Rome to study at the French Academy in Rome, where he arrived in 1690. There, he renewed his close friendship with his cousin Pierre Lepautre, also a sculptor, and struck a friendship with the academy's other fellow, the architect Gilles-Marie Oppenordt.[6]: II, 135 His time there from 1690 to 1695 was fruitful but not untroubled. The academy was plagued by a constant financial crisis,[6]: I-II passim and the premises at the Palazzo Capranica were also a rather ramshackle affair, far from the grandeur the academy would later enjoy after a move in the 18th century to the Palazzo Mancini under the directorship of Le Gros' friend Nicolas Vleughels, and eventually to the Villa Medici.

Keen to prove himself by carving a marble copy of an antique statue, after much lobbying Le Gros was eventually granted permission to do so by the director of the academy Matthieu de La Teulière and his superior in Paris, Édouard Colbert de Villacerf.[note 2] His model was the then so-called Vetturie,[note 3] an ancient sculpture then in the garden of the Villa Medici in Rome (today in the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence), chosen by La Teulière as a good example for female Roman dress – which Le Gros, nevertheless, improved upon following La Teulière's instructions, by introducing dress details found in engravings after Raphael.[6]: I, 379 Finished in 1695, she was finally shipped to Marly some twenty years later and came to Paris in 1722 where she was placed in the Tuileries Garden.[1]: Cat. 2 [note 4]

Early independence

[edit]The chapel of Saint Ignatius

[edit]In the same year 1695, Le Gros took part in a competition for a marble group to be placed on the altar of Saint Ignatius of Loyola which the Jesuit Order was erecting to its founder in their Roman mother church Il Gesù. The enterprise turned out to be the most ambitious and prestigious sculptural project Rome saw in decades.[10][note 5] The altar's architecture was designed by Andrea Pozzo who also provided oil paintings of the sculptures and reliefs as guides to their composition while leaving the details to the individual sculptors.[note 6]

Triumph of Faith over Idolatry

Religion Overthrowing Heresy and Hatred

Religion Overthrowing Heresy

[edit]Le Gros' participation was mediated by the French engraver Nicholas Dorigny and was to be kept strictly secret. Only after being firmly commissioned (his contract is also signed by Dorigny as a witness) was Le Gros allowed to tell the French Academy's director. La Teulière took the news with surprise, told him off for his disloyalty to his benefactor, the French king, and saw no other choice than to dismiss him from the French Academy, but did continue to support him. At the same time, La Teulière could not help being a little proud of his protégé who managed to beat the cream of sculptors in Rome. In particular he stressed that the models the much older Jean-Baptiste Théodon submitted for the pendant group had to be corrected several times while Le Gros' model (today in Montpellier, Musée Fabre[note 7]) was spot on from the outset.[6]: II, 173–175

Le Gros' subject was Religion Overthrowing Heresy, a dynamic group of four over-lifesize marble figures on the altar's right hand side. With her cross and a bundle of flames, the towering Religion, meaning Catholic religion, drives out heresy, personified by an old woman tearing her hair and a falling man with a serpent.[note 8] To leave no doubt as to who specifically are considered heretics, three books bear the names of Luther, Calvin and Zwingli, whose book is torn apart by a putto. Le Gros based the facial expressions on examples for the passions developed by Charles Le Brun.[1]: 38, n. 4 While the figure of Religion appears like a statue, the old woman melts into the wall decoration, the man tips over the edge of the architectural framework towards the spectator and the snake, an anecdotal detail very typical for Le Gros, hisses directly at the viewer.

This work has always been compared to Théodon's counterpart Triumph of Faith over Idolatry, carved in a much more classicising, rigid style.[note 9] The rivalry between the two Frenchmen was to play out repeatedly over the next few years. The sheer panache and virtuosity of this group launched Le Gros' career. He was in great demand and, indeed, the busiest sculptor in Rome at the time.[1]: Cat. 4

Silver statue of St. Ignatius

[edit]In 1697, with his group nearly complete, he won the competition for the altar's main image, the silver statue of St. Ignatius. It was a peculiar competition as the twelve sculptors taking part had to decide the winner themselves by pointing out the best model of their competitors. When Le Gros' victory was announced his compatriots were ecstatic and carried him through the streets in triumph.[10]: 180-181

The statue was cast in silver by Johann Friedrich Ludwig and finished in 1699. A century later it fell victim to an act of barbarism when, in 1798, it was dismantled and the head, arms and legs as well as the accompanying angels melted down for their material value during the Roman Republic. Le Gros' chasuble was left intact and the missing parts remade with slight variations in silver coated plaster from 1803 to 1804 under the supervision of Antonio Canova by one of his assistants.[note 10]

Other early works for the Jesuits and Dominicans

[edit]At the same time, Le Gros was already busy with another major Jesuit commission for the monumental altar relief of the Apotheosis of the Blessed Luigi Gonzaga in the church of Sant'Ignazio (1697–99). This altar was also designed by Pozzo, and Le Gros again had a great deal of freedom to elaborate on the composition. Building on an early idea of Pozzo's, which envisages a statue instead of a relief, Le Gros carved the figure of the saint nearly fully in the round. A superbly fine polish brings out the whiteness of the statuesque saint and gives it emphasis in the centre of the elaborately detailed relief.[1]: Cat. 10

He also started his extensive work for Antonin Cloche, the Master of the Dominicans. Apart from also being a Frenchman, Cloche was probably introduced to the sculptor by his secretary, the painter and Dominican friar Baptiste Monnoyer,[note 11] who was a friend of Le Gros' at the Académie Royale in Paris.[6]: II, 137 With the canonisation process initiated, Cloche commissioned the Sarcophagus for Pope Pius V (1697–98) of verde antico marble which was to be integrated into the existing papal tomb monument in the Cappella Sistina in Santa Maria Maggiore. Its main function is to contain the saint's body and make it visible to the faithful for veneration on limited occasions. Usually, however, it was to be hidden[note 12] by a flap made of gilded bronze which bears his effigy in very shallow relief.[note 13][1]: Cat. 9

To fulfil all these concurrent commissions Le Gros required assistants and a suitable workshop. With the help of the Jesuits, he had found an ideal space in 1695 in a back wing of the Palazzo Farnese which he was to occupy for all his life.[12]

High hopes

[edit]

All his work so far as an independent master had a clearly defined deadline: the celebrations of the Holy Year 1700.

Married life

[edit]In 1701, Le Gros married a young woman from Paris, Marie Petit. She died in June 1704 leaving Le Gros with his first son (a second son only lived for a week) who was in need of a mother. So he immediately married again in October 1704. His bride was another French woman, Marie-Charlotte, daughter of the outgoing director of the French Academy in Rome, René-Antoine Houasse. Witness to this wedding was Vleughels who at the time lived at Le Gros' studio. The couple was to have two daughters and a son (Filippo Juvarra was his godfather in 1712) who lived to be adults while his first son with Marie Petit died as a child in 1710.[1]: 13 [12]

Pope Clement XI

[edit]At the end of the year 1700, it fell to Cardinal de Bouillon as the longest serving cardinal to consecrate his friend, the art loving Giovanni Francesco Albani, as Pope Clement XI. The many years of papal frugality were over, and Le Gros decided that this was the time to be ambitious.

Elected a member of the Accademia di San Luca in 1700, he presented the terracotta relief The Arts Paying Tribute to Pope Clement XI as his reception piece in 1702. The iconography of this flattering scene was telling and unmistakably expressed the high hopes Le Gros had for the patronage of the newly elected pontiff.[1]: Cat. 17

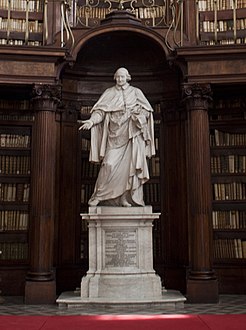

Antonin Cloche as patron

[edit]He also remained the sculptor of choice for Cloche who was eager to promote the status of the Dominicans. Following the death of Cloche's friend Cardinal Girolamo Casanate, who left his substantial collection of books and an endowment for expanding his library to the Dominicans, Le Gros was commissioned to create the cardinal's tomb in the Lateran Basilica (1700–03) and subsequently the Statue of Cardinal Casanate[note 14] in the Biblioteca Casanatense (1706–08).[13]

When the new pope offered the many niches in Saint Peter's to the religious orders to erect an honorary statue to their founders, Cloche jumped at the opportunity and commissioned the Statue of Saint Dominic from Le Gros (1702–06). It epitomises his dynamic mature style.[14] Since no other religious order saw the necessity to hurry, Saint Dominic was the very first and for decades the only monumental statue of a founder in Saint Peter's.[1]: Cat. 21

Other important commissions

[edit]Le Gros also continued to be employed by several branches of the Jesuit order for work such as the statue of St Francis Xavier (1702) in the church of Sant'Apollinare, Rome, "a marvel of delicate marble work".[15] It shows the saint reunited with his beloved crucifix which was brought back to him by a crab after it had been lost in the sea. The terracotta model in St. Petersburg, Hermitage Museum, presents an alternative idea in which the Jesuit missionary appears much fiercer, probably preaching, with the right arm raised. For the mellower mood displayed in Sant'Apollinare, Le Gros decided on a mirror image of that pose. [1]: Cat. 16

Also in 1702, the board of the Monte di Pietà in Rome, presided by the papal treasurer Lorenzo Corsini, continued the steady embellishment of their chapel which already boasted an altar relief by Domenico Guidi and had in time for the Holy Year 1700 found its architectural completion with the dome by Carlo Francesco Bizzaccheri. They were now looking to commission two large reliefs for the side walls and made a list of sculptors currently in the limelight. Their choice was to stage another head to head of Le Gros, who was to carve the relief of Tobit Lending Money to Gabael, and Théodon, creating its companion piece, Joseph Distributing Grain to the Egyptians, on the opposite wall (both 1702–05).[1]: Cat. 19 [note 15]

Stanislas Kostka

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

Video from Smarthistory |

The polychrome statue of Stanislas Kostka on his Deathbed (1702–03) is today Le Gros's best-known work. Since his normal practice was to evoke naturalistic impressions by an extraordinarily fine surface treatment of a monochrome white marble, this multi-coloured tableau-like depiction is quite untypical for Le Gros. But it would be untypical for any sculptor because it is unique in the history of sculpture on the whole.[note 16]

Unapologetically, the statue was created to emotionally move the visitor in the room where the blessed (soon to be canonised) Jesuit novice died, next to a chapel in the Jesuit novitiate at Sant'Andrea al Quirinale. The pope honoured the new devotional site with his visit – on foot – the day following its inauguration in 1703.

The figure still moves to this day, and much of the effect is due to the aura created with the staging. The site is not something one would stumble across by accident like a chapel in a church, one has to seek it out. A visitor would enter the quiet, dimly lit rooms carefully with a sense of apprehension and awe, and then see the striking silhouette of a motionless life size figure on a bed, approachable without a barrier.[note 17]

It is astonishing that one of the first things a first time visitor mentions is that Kostka looks so lifelike when, in fact, the statue couldn't be more artificial. Head, hands, feet and pillows are of white Carrara marble, the thin shirt is of a different white stone and the habit is of a black stone at the time known as "paragone". The saint's head would originally have been emphasised by a nimbus, he held an image of the Madonna in his left hand and a large crucifix would have extended from his right hand into the crook of his right elbow. Stanislas would be looking at the crucified Christ with eyes already delirious. With the large crucifix missing, an important iconographic dimension is lost today, i.e. the connection between Stanislas and Christ (similar to the statue of St. Francis Xavier of the same time) which would also round up the composition.[note 18] The mattress, bed cover with bronze fringes and bed step are from coloured ornamental stones common to Roman baroque art but used in a highly original and effective manner.[1]: Cat. 20

Bouillon Monument

[edit]

At some point after 1697, Le Gros was employed by Emmanuel-Théodose de La Tour d'Auvergne, cardinal de Bouillon to create the dynastic monument for his family to be erected in a funerary chapel in Cluny Abbey, of which the cardinal was the abbot. Apart from being a compatriot, Bouillon might have known the sculptor through the Jesuits as he habitually lived as their guest in the Jesuit novitiate at Sant'Andrea al Quirinale. Le Gros's work was completed by 1707 and sent to Cluny, where it arrived in 1709. He worked on this project in as much a French manner as he ever would and invented a spectacular sepulchral monument, at once continuing in the French baroque tradition as well as opening up new formal and iconographic avenues.

The chapel was meant to receive several family members, including the cardinal himself, but first and foremost his parents, Frédéric Maurice de La Tour d'Auvergne, Duc de Bouillon and Éléonor de Bergh, Duchesse de Bouillon. Depicted as the main characters in the centre of the monument their grouping and gestures allude to the fact that Éléonor was instrumental in converting her husband to catholicism. Another important component was the heart of the duke's brother, the national hero Turenne, enclosed in a heart shaped container of gilded silver and carried towards heaven by a youthful angel who rises from a heraldic tower of white marble which links the family name La Tour to the biblical tower of David. Together with some other sculptures outside the chapel (not planned to be made by Le Gros and, in fact, never executed), the iconographic message was the postulation of a royal rank and sovereignty of the family dating back to the 9th century, the same message Cardinal de Bouillon tried to support by commissioning a written history of his ancestry from the historiographer Étienne Baluze,[note 19] published in 1708 and containing an engraving of the envisaged funeral chapel with an idealised view of Le Gros's monument.

None of this highly original concept influenced the development of monumental funerary sculpture. Apart from a thorough inspection by royal officials to determine whether they expressed any pretentious dynastic claims, the sculptures were not even unpacked in Cluny due to the fact that Cardinal de Bouillon so completely fell out with his cousin, the Sun King, that he was declared an enemy of the state and all construction stopped. Le Gros' marbles and bronzes were stored, undisturbed in their sealed crates, for nearly 80 years. In the aftermath of the French Revolution they were in danger of being sold as stone material together with Cluny abbey but saved by Alexandre Lenoir who wanted them for his Musée des Monuments français.

The animated marble figures of the Duke and Duchess de Bouillon together with the angel (minus Turenne's heart) and a finely detailed relief showing the duke as a battle hero never made it to Paris and are today installed at the Hôtel-Dieu in Cluny.[note 20] A fragment of the heraldic tower is kept in the granary of the abbey.[1]: Cat. 11 [16]

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

San Giovanni in Laterano

Lateran Apostles

[edit]At the end of 1702, Pope Clement XI announced his intention to finally have Borromini's colossal niches in the Lateran basilica filled with twelve heroic-scaled figures of the Apostles.[note 21] Clement's idea was very similar to filling the niches of St. Peter's initiated at the same time: get your church embellished but find others to pay for it. So, he called on prelates and princes to sponsor individual statues but handed the task to choose sculptors to a committee created to run the project. The statue of St. Peter he intended to finance himself and had Théodon commissioned.

Like Théodon, Le Gros was given not only one but two statues:[17]: 109 Saint Bartholomew (1703–12)[1]: Cat. 23 who displays his own flayed skin,[note 22] sponsored by the pope's treasurer Lorenzo Corsini,[note 23] and Saint Thomas (1703–11), sponsored by King Peter II of Portugal.

From the outset it was recognised that the overall unity of all the Apostle statues was of paramount importance. The architect Carlo Fontana acted as a consultant to work out an appropriate size of the proposed sculptures and, more importantly, the ageing painter Carlo Maratti, the pope's favourite artist, was given the task to achieve a stylistic unity by preparing drawings for each statue which were then given to the sculptors as a guideline.[17]: 98-105 This forced submission enraged many of them who, in 1703, voiced their discontent,[17]: 263 Théodon even resigned because of it, eventually returning to France in 1705.[note 24].

Le Gros went one step further and decided to challenge Maratti's authority by submitting a model which was radically different from the latter's sober, classicising style. With his model for Saint Thomas from around 1703–04, the most intricate and detailed terracotta he ever produced, he harked back to the highly emotional baroque of Gianlorenzo Bernini's St. Longinus. He was undoubtedly aware that, if he prevailed and his model was accepted by the pope's committee, all the other sculptors would have to follow suit stylistically. So this, in effect, was Le Gros' attempt to establish himself as the artistic leader of the Eternal City.[1]: 14-15

His model was not approved and the Late Baroque classicism, as Wittkower[18] calls it, prevailed. While Le Gros was the only sculptor who was not held to work from drawings by Maratti,[note 25][17]: 218 he must have been forced into an act of self-censorship. While essentially the same figure, each and every exuberance was ironed out in his monumental marble figure: the drapery is more ordered, the head lost its visionary vigour, the unruly pages of the book gave way to a carpenter's square, the naturalistic rock became a flat plinth, the weathered tomb stone turned pristine and, of course, the putto vanished. A dynamic group of a saint with a putto in the landscape became a solid statue in a niche.[1]: Cat. 22

While Le Gros was put in his place, he was not down and out. When it transpired that the undistinguished Florentine sculptor Antonio Andreozzi would not finish his Saint James the Greater, efforts were made in 1713 to win over Louis XIV to take on the patronage and employ Le Gros, but to no avail.[6]: IV, 230, 240 [17]: 123

Later works

[edit]

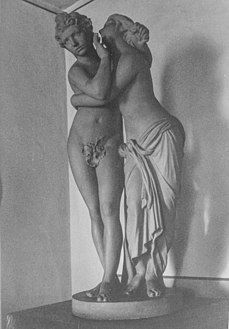

Le Gros thrived on playful invention. When, some time between 1706 and 1715, he was asked by the Portuguese ambassador to add heads, hands and legs to a fragmented antique group of Amor and Psyche, he deliberately turned the love story on its head and transformed it to the tale of Caunus and Byblis in which Caunus vehemently defends himself against the sexual advances of his sister. Le Gros' creation quickly became popular and triggered a rafter of drawings, reproductions and copies by for example Pompeo Batoni, Francesco Carradori, Martin Gottlieb Klauer and, best known of all, Laurent Delvaux who carved two marble versions. Le Gros' work soon ended up in Germany where several plaster casts were made. Some time later it was purified back to Amor and Psyche but later destroyed in a fire. The most faithful impression of what it looked like is the plaster cast in Tiefurt House near Weimar.[1]: Cat. 39 [19]

In 1708–10 Le Gros collaborated with his close friend, the architect Filippo Juvarra, in the creation of the Cappella Antamori in the church of San Girolamo della Carità, Rome. His statue of San Filippo Neri is set against a large backlit coloured glass window and seems to dematerialise in the warm yellow orange glow. Drawings by both Le Gros and Juvarra demonstrate that each of them contributed to finding the right composition for the sculpture and tried a number of different poses.[20] Le Gros also made many putti and cherubim and two plaster reliefs for the ceiling showing scenes from Neri's life. The exquisitely crafted chapel is one of the very few traces of Juvarra's activities in Rome.[1]: Cat. 30

With the vast, lavish Monument to Pope Gregory XV and cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi in Sant'Ignazio, Le Gros conceived his last work for the Jesuits between about 1709–14. It singularly combines the tombs of both the pope and his cardinal-nephew and celebrates their merits from a pronounced Jesuit point of view[note 26] as the inscription explains: ALTER IGNATIUM ARIS. ALTER ARAS IGNATIO (one raised Ignatius to the altars, the other erected altars for Ignatius). This alludes to the facts that Gregory canonised the saint and Ludovico built the church of Sant'Ignazio. The concept is highly theatrical with a large curtain (made from coloured marble) being drawn back by two Famae (both the work of Pierre-Étienne Monnot from designs by Le Gros) to reveal the protagonist. This curtain obscures the wall behind and creates the illusion that the monument has the rare quality of being free standing rather than attached to the wall as is the norm.[21]: 177 The composition also makes use of the monument's location in the only chapel with a side entrance to the church (to the right of the monument) by turning several figures directly towards visitors entering from there and inviting them in – an effect which today is hard to appreciate as the door is no longer in use.[1]: Cat. 31

From 1711 to 1714 followed the Cappella di S. Francesco di Paola in San Giacomo degli Incurabili, for which Le Gros was the architect – which basically means he was in charge of all its decoration – and the sculptor of a large relief showing the saint in adoration of an old venerated image of the Madonna and child, intervening to cure the sick.[1]: Cat. 34

Decline

[edit]In 1713, he managed to alienate the Jesuits by stubbornly repeating his proposal to transfer his own statue of Stanislas Kostka on his Deathbed into the church of Sant'Andrea al Quirinale as a centrepiece for the newly decorated chapel of saint Stanislas.[1]: 77-78 [22][note 27] At the same time, all efforts of deciding who should be commissioned with the last Lateran apostle were at a stalemate with, it seems, three serious contenders: Le Gros, Angelo de' Rossi and Rusconi. The latter had already produced three apostles and was by then clearly favoured by Pope Clement XI, but no decision was made.[17]: 123, 332

In 1714, Le Gros' father died in Paris and he himself was close to death's door, suffering from gall stones.[1]: 16

Paris

[edit]In order to have an operation done and also to settle his inheritance, in 1715 he travelled to Paris, where he stayed with his great friend Pierre Crozat who managed to arrange his travel on a royal ship. Very rich, but with humorous irony nicknamed Crozat le pauvre (Crozat the poor) because his brother Antoine was even wealthier, he was a renowned collector and patron of the arts. His house was at the centre of artistic life for connoisseurs and established as well as up and coming artists. There, Le Gros would certainly have met the ageing Charles de la Fosse who lived with Crozat but also his young protégé Antoine Watteau. In addition Le Gros renewed his friendships with Oppenordt and Vleughels. Crozat had Le Gros decorate a cabinet in his Parisian house and the chapel in his magnificent country retreat, the Château de Montmorency (both destroyed).

Both Crozat and Oppenordt were on good terms with the Regent, so Le Gros would have had a good start had he decided to stay in Paris. He also acted as a go-between in Crozat's long negotiations (1714–21) to acquire the art collection of Queen Christina of Sweden for the regent. But he had great trouble with the art establishment, and the Académie royale would not admit him easily into their ranks despite his status as an internationally acclaimed artist. Rebuffed, Le Gros returned to Rome in 1716.[1]: 16-19

Rome

[edit]Back in Rome, the last sad chapter of his life unfolded. His absence had been a great excuse to give the last Lateran apostle to Rusconi. The reason given was that de' Rossi was dead, Le Gros abroad, and therefore Rusconi the only good sculptor available.[17]: 123, 332

It was, however, of far greater consequence what happened at the Accademia di San Luca. Led by Marco Benefial and Michelangelo Cerruti (both non-academicians), a protest arose in 1716 against newly introduced rules of the academy which subjected non-members to financial injustice. Francesco Trevisani and three other academicians (Pasquale de' Rossi, Giovanni Maria Morandi and Bonaventura Lamberti) distanced themselves from subscribing to these new rules, and Le Gros sided with them on his return. As a result, all five were unceremoniously expelled. This meant that they were then unable to carry out any more public commissions in Rome in their own right.[1]: 18-19

The rich Roman art market was effectively closed to Le Gros, and he had to settle for a few works outside. After being first approached by the Benedictine abbey of Montecassino in 1712, in 1714 he gave in and took on three statues for the abbey's Chiostro dei Benefattori at a bargain price. These now became his main focus. At the time of his death, the statue of Pope Gregory the Great was finished and Emperor Henry II only needed finishing touches. The third, Charlemagne, was hardly started and subsequently taken on by Le Gros' loyal assistant Paolo Campi as his own work. During the heavy bombing of Montecassino in World War II, Pope Gregory was nearly completely destroyed and is now heavily restored while Henry II suffered less damage and remains recognisable as a work by Le Gros.[1]: Cat. 40–41

Without doubt due to the intervention of Juvarra, who was by then architect to the Duke of Savoy, Le Gros created two female saints for Juvarra's facade of the church of S. Cristina in Turin (c. 1717–18). Upon their arrival, the statues of Saint Christina and Teresa of Avila were considered too beautiful to be exposed to the elements and brought into the church's interior (1804 transferred to Turin Cathedral) and to be replaced on the facade by copies by a local sculptor. This flattery was probably intended to be a reminder of a similar honour which was bestowed on Bernini half a century earlier with regards to his two angels for Ponte Sant'Angelo.[1]: Cat. 45

In a letter from 6 January 1719 to Rosalba Carriera, hoping to introduce the two on her planned visit to Rome, Crozat described Le Gros as "without question the best sculptor there is in Europe, and the most honest man and the most endearing there is."[23]

While Le Gros' great achievement was appreciated elsewhere, he would wait in vain for a similar adulation in Rome. Rusconi received a knighthood from Clement XI for his contribution to the Lateran project in late 1718 while Le Gros went empty handed.[17]: 123

Pierre Le Gros died from pneumonia half a year later on 3 May 1719 and was buried in the French national church in Rome. If we believe Pierre-Jean Mariette, disappointment advanced his early death:

"If he was indisposed against the Parisian academy, he was even more piqued by the honours conferred on Camillo Rusconi for the figures this able sculptor has made for Saint John Lateran. He expected to at least share them with him, and that would have been right; ... one more miserable cross[note 28] might have preserved him for us, because one suspects that the chagrin has advanced his days."[24]

Only in 1725, with the painter Giuseppe Chiari being its principe, were the five dissenters rehabilitated and reinstated as members of the Accademia di San Luca, four of them posthumously as only Trevisani was still alive at the time.[1]: 18

Importance

[edit]

Today, Le Gros is largely forgotten but shares this fate with almost all the artists working in Rome in his time. After a blanket condemnation of the Baroque period by critics from the 18th to well into the 20th century, Gianlorenzo Bernini, Francesco Borromini and a few other 17th century artists have now been given their rightful place in the pantheon of artistic geniuses. But even the great Alessandro Algardi, while certainly given his dues by art historians,[25] is not anchored in the public consciousness,[26] much less so the following generations of Maratti or Fontana, and then Le Gros and Rusconi.[note 29] During their lifetime however, they were regarded throughout Europe as outstanding figures, valued as exemplary by generations of young artists.

An impartial look shows Le Gros as a driving force in an international environment. While family life was very French, close friends included painters such as the Dutch Gaspar van Wittel, the Frenchmen Vleughels and Louis de Silvestre as well as the Italian Sebastiano Conca, architects such as the Italian Juvarra and the Frenchman Oppenordt, and the sculptors Angelo de' Rossi as well his loyal students and right-hand men Campi and Gaetano Pace. In addition, the need for assistants brought a bevy of young sculptors and painters from all over Europe to his studio over the years like the Englishman Francis Bird and the Frenchman Guillaume Coustou who frequented his workshop before 1700, both eventually becoming significant artists in their home countries. In the 1710s we find in his workshop the German painter Franz Georg Hermann and the still very young Carle van Loo who studied drawing with Le Gros.[12] In addition to passing on his style through students, copies and versions of important statues such as his St. Dominic, St. Ignatius or the Apostle Bartholomew can be found all over Europe and engravings were disseminated of his Luigi Gonzaga and Stanislas Kostka. Le Gros' influence didn't end with his death as his works were also studied much later as evidenced in sketches by Edme Bouchardon. Even in the second half of the 18th century connoisseurs in Paris described his Vetturie as an exemplary masterpiece, the quality of which far exceeds the ancient model. The importance of Le Gros for European art in the 18th century is, therefore, beyond question.[1]: 34-35 and passim

That said, because of his nearly exclusive presence in Rome, he must be seen within the context of Italian art history and made virtually no direct impact on the development of French art of his own time.[14] His French contemporaries would have heard about him but wouldn't have seen his works. His Vetturie, a student work, arrived in France 20 years overdue and the Bouillon Monument was not even unpacked until the end of the 18th century and, therefore, not known to anybody.[15] Moreover, the exuberance of Le Gros' work would have met with reserve or even disapproval[14] in Versailles just as Bernini's did in the 1660s.

At the same time, it is impossible to characterise his art as purely Italian. His artistic training at the Académie royale and the experience in the workshops of his father and uncles gave him a very different starting point. He built on this experience and mixed it with an admiration for Bernini's high baroque. His love for fine detail is something he shared with older French sculptors like François Girardon and Antoine Coysevox. Imbued with the French academic practice of searching for exemplary prototypes, Le Gros looked very closely at all the art around him and found solutions by today less well known sculptors like Melchiorre Cafà and Domenico Guidi but also painters like Giovanni Battista Gaulli helpful, and he adapted them for his own work, often transformed to such a degree that the prototype is hard to pinpoint. There were only very few artists who worked successfully in a similarly playful style as Le Gros in early 18th century Rome, namely Angelo de' Rossi, Bernardino Cametti and Agostino Cornacchini. But the mood of the time drifted more and more towards classicism and made them a dying breed.[1]: 28-30

Style

[edit]

According to Gerhard Bissell, Le Gros was a sculptor of brilliant technical ability:

The most virtuoso marble worker of his time, he excelled in convincing the eye to see the depicted materials rather than stone. His surfaces are so nuanced they nearly appear as different colours. And yet, he achieved that very rare feat of integrating these fine details into monumental sculptures without appearing grotesque.[15]

He always tended to compose his sculptures like a relief. For his picturesque approach, an expansive shape mattered more to him than the distribution of mass and space. While the detail as well as the large form are very three-dimensional, their volume is usually tied into a system of layers. This leads by no means to a single point of view. Quite the contrary because Le Gros developed all his composition into space and entices the viewer to go around the figure. While a classicist like Rusconi linked a spatial development closely to the anatomy of the figure, Le Gros achieved this with an abundance of highly malleable drapery and extrovert gestures. In addition, he showed a keen sense for nuanced effects of light and shadow, whether it was to make the heavily polished, white as snow figure of Luigi Gonzaga stand out, or to cast Filippo Neri into a mystical shade. All of Le Gros' work is characterised by a dynamic of far and near view. It is worth getting close up to even his most heroic-scale figures.[1]: 21-30

Gallery

[edit]Chronological gallery of most of the major works by Le Gros not already illustrated - some dates are uncertain or overlap, therefore the sequence is only roughly chronological.

-

Silver statue of St. Ignatius, 1697–1699, Rome, Il Gesù

-

S. Luigi Gonzaga in Gloria, 1697–99, Rome, Sant'Ignazio

-

Tomb of St. Pius V, 1697–98, Rome, S. Maria Maggiore

-

Tomb of Cardinal Girolamo Casanate, 1700–1703, Rome, S. Giovanni in Laterano

-

St. Francis Xavier, 1702, Rome, Sant'Apollinare

-

Stanislas Kostka on his Deathbed, 1702–03, Rome, Jesuit Novitiate

-

St. Dominic, 1702–06, Rome, St. Peters

-

The Duc de Bouillon in Battle, finished by 1707, Cluny, Hôtel-Dieu

-

Frédéric Maurice de La Tour d'Auvergne, Duc de Bouillon, finished by 1707, Cluny, Hôtel-Dieu

-

Éléonor de Bergh, Duchesse de Bouillon, finished by 1707, Cluny, Hôtel-Dieu

-

Tomb of Cardinal Cinzio Aldobrandini, 1705–1707, architecture by Carlo Francesco Bizzaccheri, sculpture by Le Gros, Rome, San Pietro in Vincoli

-

Statue of Cardinal Girolamo Casanate, 1706–1708, Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense

-

St. Bartholomew, c. 1703–1712, Rome, S. Giovanni in Laterano

-

Caunus and Byblis, plaster cast after Le Gros, Schloss Tiefurt

-

Chapel of St. Francesco di Paola, 1711–1714, Rome, S. Giacomo degli Incurabili

-

St. Francesco di Paola intervening to cure the sick, 1711–1714, Rome, S. Giacomo degli Incurabili

-

Emperor Henry II, 1714–1719, Montecassino, Chiostro dei Benefattori

-

Statues of St.Christina and St.Teresa of Avila, c. 1717–1719, Turin, Duomo

-

Angels and putti above the statue of Saint Sebastian by Paolo Campi, c. 1717–1719, Rome, Sant'Agnese in Agone

Notes

[edit]- ^ The engraver Jean Le Pautre (born 1618) has been mistaken for Marie's father due to the fact that he had a brother, also called Jean Le Pautre (born 1622), a builder and architect, who is, in fact, Marie's father. See Lepautre family tree in the endpapers of Souchal[3]: II

- ^ Many letters between La Teulière and Villacerf from 1692 onwards deal with this.[6]: I, 226–379 passim

- ^ This mis-identification, one of many, refers to Veturia, the mother of Coriolanus. Other names the statue was given over the centuries include Thusnelda, Polyhymnia, Venus of Lebanon, Silence.

- ^ Long after Le Gros' death the Vetturie elicited a discussion whether a modern copy could surpass an antique original,[7] an argument reminiscent of the literary Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns of the late seventeenth century.

The statue was admired throughout the 18th century and judged by many as actually having surpassed its antique prototype.[8] When a student at the French Academy in Rome in 1781, Louis-Pierre Deseine opted to copy the Arrotino (a celebrated antique statue which Deseine, curiously, regarded as mediocre) rather than a more beautiful antique to be able to improve on it quoting Le Gros' example.[6]: XIV, 130 s.

Edmond Texier, who then called her a Vénus silencieuse, still rated her "a copy nearly being an original" ("copie valant presque un original") in 1852.[9] - ^ The chapel and its propaganda value has been discussed in great detail by Evonne Levy in her dissertation A canonical work of an uncanonical era. Re-reading the chapel of Saint Ignatius (1693–99) in the Gesù of Rome, Ph.D. thesis Princeton University 1993; see also: ead., Propaganda and the Jesuit Baroque, Berkeley, California (University of California Press) 2004.

- ^ As La Teulière explains with respect to the bronze relief by René Frémin[6]: II, 176

- ^ The terracotta's previous owner was most likely Le Gros' friend Pierre Crozat[3]: II, Cat. 4b

- ^ The group is sometimes called Religion Overthrowing Heresy and Hatred which is not correct as both, the old woman and the falling man, stand for heresy.

- ^ The juxtaposition of both groups based on Théodon's and Le Gros' sculptures has been replicated on several altars in the 18th century, e.g. Burchard Precht's for Uppsala Cathedral (currently in Gustaf Vasa Church, Stockholm).

- ^ Pecchiai[10]: 182-183 assumes that this assistant of Canova's was Adamo Tadolini which is impossible.[2]: 134 While precocious, Tadolini was then much too young (born 21 December 1788) and only started studying at the Academy in Bologna in that very year 1803 when the restoration was begun. He only became Canova's pupil in 1814.[11]

- ^ He was the son of Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer and the brother of Antoine Monnoyer, both painters of mostly flower still lifes.

- ^ This rare exposition of the relics has become unfashionable in modern times and the viewing situation has been reversed: the flap is usually open displaying the body while it is rare to see Le Gros' relief.

- ^ Both, composition and flatness are very reminiscent of Germain Pilon's famous gisant of Valentine Balbiani (c. 1583).

- ^ See also some notes on the statue's placement in the Wikipedia entry on the Biblioteca Casanatense

- ^ The chapel and its decoration is the subject of: Antje Scherner, Die Kapelle des Monte di Pietà in Rom. Architektur und Reliefausstattung im römischen Barock, Weimar (VDG) 2009 (in German).

- ^ There are only a few earlier examples of black, purple or alabaster garments combined with head and extremities of white marble or bronze, and none as elaborate as Le Gros'. Closest are antique portrait busts with porphyry bodies and, similarly, 16th and 17th century Roman funeral busts of clergy. In France are some medieval statues of nuns wearing habits of black marble with the best known being Marie de Bourbon (died 1401), prioress of the Dominicans of Saint-Louis de Poissy, in the Louvre. Some statues by Nicolas Cordier come closer to Le Gros treatment but put the emphasis on being exotic and precious. It is difficult to come up with more examples.

- ^ The Cappellette di San Stanislao (little chapels of Saint Stanislas), as they were called, looked quite different when Le Gros' figure was first placed there. Later findings indicated a slightly different location of his death, in the adjacent corridor, and lead to the first transformation of the Cappellette in 1732–33 by erecting an altar on the real spot and opening up the wall behind the statue. In the 19th century, the Cappellette were again remodelled and a painting by Tommaso Minardi placed over the saint's head in 1825, replacing some previous fresco paintings. The situation we see today was created in 1888–89 when the novitiate was partly demolished and the Cappellette reconstructed, using old materials, but turned 180°.[1]: 78-79

- ^ The halo and the original Madonna image and crucifix are lost. Since the hands obviously held something, the custodians placed a variety of different objects in them over the years, from a rosary to a small crucifix to flowers etc. This might vary from one visit to the Cappellette to the next.

- ^ See also: Étienne Baluze.

- ^ The current display can be seen at the Guide de tourisme, Hôtel-Dieu.

- ^ The long and complex history of the project has been thoroughly researched by Michael Conforti in his unpublished dissertation The Lateran Apostles, Ph.D. thesis Harvard University 1977); a brief version is: Michael Conforti, Planning the Lateran Apostles, in: Henry A. Millon (Ed.), Studies in Italian Art and Architecture 15th through 18th Centuries, Rome 1980, pp. 243–260 (Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 35).

- ^ A marble replica of reduced size, with some variations, is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Corsini was created a cardinal in 1706. The inclusion of the sculpture of Saint Bartholomew as a major work identifying Le Gros in the anonymous drawing with his portrait shows that it and/or its sponsor were obviously of great importance to Le Gros.

- ^ Théodon never made more than small models for the Saint Peter and the Saint John the Evangelist.[17]: 118–119

- ^ Pierre-Étienne Monnot did not receive a Maratti drawing for his Saint Peter but did have one for his Saint Paul[17]: 331

- ^ The propaganda value for the Jesuits as well as the financial background is discussed by Büchel, Karsten and Zitzlsperger[21]

- ^ Le Gros did offer to make a plaster copy of his Stanislas Kostka for the cappellette. The Jesuits countered that the cappellette would lose out if their devotional focus point was removed and replaced by a mere copy. They also argued that the marble figure would have less impact in the church.

- ^ Meaning a knighthood

- ^ Fontana was researched by architectural historians for a long time, in particular by Hellmut Hager.[27] Maratti has been the subject of many scholarly articles and especially been studied for decades by Stella Rudolph although her repeatedly announced monograph never saw the light of day.[28] There is a monograph on Rusconi by Frank Martin[29] and dissertations on Monnot[30] and Théodon.[31]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Gerhard Bissell, Pierre le Gros, 1666–1719, Reading, Berkshire 1997.

- ^ a b Robert Enggass, Early Eighteenth-Century Sculpture in Rome, University Park and London (Pennsylvania State University Press) 1976.

- ^ a b c François Souchal, French Sculptors of the 17th and 18th Centuries. The Reign of Louis XIV, vol. II, Oxford (Cassirer) 1981, vol. IV, London (Faber) 1993.

- ^ Thomas Hedin, The Sculpture of Gaspard and Balthazard Marsy, Columbia (University of Missouri Press) 1983, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Legros (Le Gros), Jean, in: Ulrich Thieme, Felix Becker (editors): Allgemeines Lexikon der Bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, XXII, Leipzig (E. A. Seemann) 1928, p. 575.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Anatole de Montaiglon and Jules Guiffrey (eds.), Correspondance des directeurs de l’Académie de France à Rome avec les surintendants des bâtiments, vol. I-XVIII, Paris 1887–1912.

- ^ Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500–1900, (Yale University Press) 1981, p. 40.

- ^ M.-F. Dandré-Bardon, Traité de Peinture suivi d’un essai sur la sculpture, Paris 1765, Vol. II, pp. 190–191 (Minkoff Reprint 1972).

- ^ Tableau de Paris

- ^ a b c Pio Pecchiai, Il Gesù di Roma, Rome 1952, pp. 139–196 (in Italian).

- ^ Gerhard Bissell, Tadolini, Adamo, in: Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon, vol. 107, Berlin (de Gruyter) 2020, p. 413.

- ^ a b c Olivier Michel, L’Accademia, in: Le Palais Farnèse, Rome 1981, Vol. I/2, pp. 567–609, in particular pp. 572–579 (in French).

- ^ Gerhard Schuster, Zu Ehren Casanates. Père Cloches Kunstaufträge in der Frühzeit der Biblioteca Casanatense, in: Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz, Vol. 35, 1991, pp. 323–336.

- ^ a b c Michael Levey, Painting and Sculpture in France 1700–1789, (Yale University Press) 1993, p. 82 (originally published as part of the Pelican History of Art: Wend Graf von Kalnein and Michael Levey, Art and Architecture of the Eighteenth Century in France, Harmondsworth 1972 and several new editions).

- ^ a b c Gerhard Bissell, On the Tercentenary of the Death of Pierre Le Gros, Italian Art Society blog, 2 May 2019

- ^ See also: Mary Jackson Harvey, Death and Dynasty in the Bouillon Tomb Commissions, in: Art Bulletin 74, June 1992, pp. 272–296.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Michael Conforti, The Lateran Apostles, Ph.D. thesis Harvard University 1977.

- ^ Rudolf Wittkower, Art and Architecture in Italy 1600–1750 (The Pelican History of Art), Harmondsworth (5th ed.) 1982, p. 436.

- ^ Gerhard Bissell, Haud dubiè Amoris & Psyches imagines fuerunt statuæ istæ, in: Max Kunze, Axel Rügler (ed.), Wiedererstandene Antike. Ergänzungen antiker Kunstwerke seit der Renaissance (Cyriacus. Studien zur Rezeption der Antike, Band 1), Munich 2003, pp. 73–80.

- ^ Gerhard Bissell, A "Dialogue" between Sculptor and Architect: the Statue of S. Filippo Neri in the Cappella Antamori, in: Stuart Currie, Peta Motture (ed.), The Sculpted Object 1400–1700, Aldershot 1997, pp. 221–237.

- ^ a b Daniel Büchel, Arne Karsten and Philipp Zitzlsperger, Mit Kunst aus der Krise? Pierre Legros' Grabmal für Papst Gregor XV. Ludovisi in der römischen Kirche S. Ignazio, in: Marburger Jahrbuch für Kunstwissenschaft 29:2002, pp. 165–197.

- ^ See also: Francis Haskell, Pierre Legros and a Statue of the Blessed Stanislas Kostka, in: Burlington Magazine, vol. 97, 1955, pp. 287–291.

- ^ Le Gros "sans contredit, est le meilleur sculpteur qu’il y ait en Europe, et le plus honnête homme et le plus aimable qu’il y ait", as quoted by Vittorio Malamanni, Rosalba Carriera, in: Le Gallerie Italiane 4:1896–97, p. 51.

- ^ "S’il fut indisposé contre l’Académie de Paris, il étoit encore plus piqué des honneurs qu’avoient procurés à Camille Ruscone les figures que cet habile sculpteur avoit faites pour Saint-Jean de Latran. Il s’attendoit à les partager du moins avec lui, et cela étoit juste; ... Une misérable croix de plus nous l’auroit peut-être conservé, car on soupçonne que le chagrin avoit avancé ses jours." Pierre-Jean Mariette, "Abecedario", vol. III, edited by Philippe de Chennevières and Anatole de Montaiglon, in: Archives de l’Art Français 6, 1854–56, p. 120.

- ^ First and foremost Jennifer Montagu, Alessandro Algardi, New Haven (Yale University Press) 1985.

- ^ See Montagu's remarks in her interview with João R. Figueiredo in Forma de vida.

- ^ The latest extensive collection is: Giuseppe Bonaccorso and Francesco Moschini (ed.), Carlo Fontana 1638–1714, Rome (Accademia Nazionale di San Luca) 2017.

- ^ Rudolph's publications related to Maratti.

- ^ Frank Martin, Camillo Rusconi. Ein Bildhauer des Spätbarock in Rom, Berlin and Munich (Deutscher Kunstverlag) 2019.

- ^ Stephanie Walker, The sculptor Pietro Stefano Monnot in Rome, 1695 – 1713, Ph.D. thesis New York University 1994.

- ^ Alicia Adamczak, De Paris à Rome. Jean-Baptiste Théodon (1645–1713) et la sculpture française après Bernin, Thèse de doctorat Université de Paris IV 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Gerhard Bissell, Pierre le Gros, 1666–1719, Reading, Berkshire 1997, ISBN 0-9529925-0-7 (in German).

- Gerhard Bissell, Le Gros, Pierre (1666), in: Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon online, de Gruyter, Berlin 2014 (in German).

- Robert Enggass, Early Eighteenth-Century Sculpture in Rome, University Park and London (Pennsylvania State University Press) 1976.

- Pascal Julien, Pierre Legros, sculpteur romain, in: Gazette des Beaux-Arts 135:2000(no. 1574), pp. 189–214 (in French).

- François Souchal, French Sculptors of the 17th and 18th Centuries. The Reign of Louis XIV, vol. II, Oxford (Cassirer) 1981, vol. IV, London (Faber) 1993.