Pictograph Cave (Billings, Montana)

Pictograph Cave | |

Pictograph Cave | |

| Location | Yellowstone County, Montana, United States |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Billings, Montana |

| Coordinates | 45°44′15″N 108°25′53″W / 45.7374524°N 108.4315219°W[1] |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000439 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | July 19, 1964[2] |

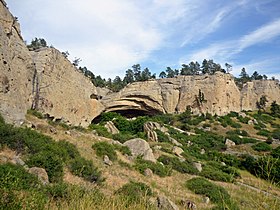

Pictograph Cave is an area of three caves (Pictograph, Middle, and Ghost caves) located 5 miles (8.0 km) south of Billings, Montana, United States, preserved and protected in the 23-acre (9.3 ha) Pictograph Cave State Park.[3]

Excavation of the three caves began in 1937, and they were the site of some of Montana's first professional archeological studies. Over 30,000 artifacts have been identified, with at least 20,000 animal remains recovered from the site. Species range from large mammalian species, including bison (Bos bison) and elk (Cervus elaphus), to various species of herpetiles (reptiles and amphibians) and avies (birds). The presence of these remains result from human predation, processing and consumption as well as non-human (carnivores and raptors) predation and individual species who lived and died in and around the site.

Paintings known as pictographs are still visible in Pictograph Cave, which is the largest of the three caves. The pictographs are thought to be between 200 and 2,100 years old. However their interpretations are still debated over. The oldest pictograph is that of a turtle, radio-carbon dated to be approximately 2,100 years old. These pictographs are paintings of animals, warriors, and even rifles that document the story of the Native Americans of the area for thousands of years.

The site was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1964.[2]

State park

[edit]

The caves are part of Pictograph Cave State Park, which features paved trails to the caves with interpretive signs about the paintings, the area's geology and vegetation. The park encompasses 23 acres (9.3 ha) and includes a visitor center and picnic facilities.[3][4]

The natural shelters are nestled in a sandstone bluff on a well-traversed path extending south from the confluence of Bitter Creek and the Yellowstone River, 6 miles (9.7 km) south of Billings. The cave complex has long been a site of mystical power,[citation needed] a culturally significant gathering place for American Indians. On the interior wall of Pictograph Cave (the only one containing rock art), archaeologists discovered 106 pictographs, painted between 2,145 and 200 years ago. The walls were covered with red, white, and occasionally yellow figurines over drawings originally painted with black. They also found stone and bone tools, moccasins, arrow shafts, basketry, grinding stones, and fire-starting tools. Excavations turned up jewelry too, such as pendants, bracelets, and beads crafted of seashells acquired from Pacific Coast Indians. The excavation was led by H. Melville Sayre of the Montana School of Mines. He later hired Oscar Lewis, an archeologist from the Glendive WPA crew, to help supervise the dig. William Mulloy replaced Sayre as the Project director from Oct. 1940 to Feb. 1942.

Development and perception of the site

[edit]

Conversion of the site into a State Park was not accomplished easily. The 22-acre property was originally purchased by the State of Montana in 1937 and placed under the jurisdiction of the Montana Highway Commission.

During the excavation period covering 1938 to 1941 (which included notable discoveries such as the "barbed harpoon points of the Eskimo culture, made of caribou horn," the graves of nine plus individuals, and over 30,000 artifacts), over 10,000 visitors were recorded at the site. During that time, public interest was so intense that a small museum and visitor center was constructed. The building was also used to process artifacts that were continually flowing from the caves. L. B. McMullen, then President of Eastern Montana Normal School, was instrumental in developing the original museum located at the site.

When the excavation was halted due to the onset of World War II, interest in the site waned. Visitation at the site was not controlled, the artifacts were not tracked well (most still cannot be accounted for today), and the museum at the site was broken into numerous times and eventually burned by vandals.

In 1963 Mayor Willard Fraser signed an agreement stating that the City of Billings would take over administration of the park from the Montana State Department of Highways. This move was met with criticism from aldermen who expressed concerns over the city's ability to monitor the park, assume liabilities, and provide services. The distance of the park from the city was also of major concern. "We'd just be inviting kids to raise all kinds of hell" was the position of Alderman Joe Leone. Regardless of their opposition, Mayor Fraser saw the potential to attract tourists to the site (Billings Gazette 1963). The site was designated a National Historic Landmark on July 19, 1964. The city turned over the caves' management to the Parks Division of the Montana Department of Fish and Game in 1969; the site became a state park in 1991.[5]

See also

[edit]- National Register of Historic Places listings in Montana

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Yellowstone County, Montana

References

[edit]- ^ "Pictograph Cave State Park". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ a b "List of National Historic Landmarks by State". National Park Service. December 2016. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ a b "Pictograph Cave State Park". Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ^ "Pictograph Cave State Park". Montana Office of Tourism. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ Kooistra-Manning, Ann. "Pictograph Cave State Park". Montana Office of Tourism, reprinted from Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 51 (Winter 2001), pp. 79-81. Archived from the original on June 26, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

External links

[edit]Pictograph Cave.

- Pictograph Cave State Park Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks

- Pictograph Cave State Park Trail Map Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks

- Rock art in North America

- Caves of Montana

- State parks of Montana

- Archaeological sites on the National Register of Historic Places in Montana

- National Historic Landmarks in Montana

- Protected areas of Yellowstone County, Montana

- Show caves in the United States

- Landforms of Yellowstone County, Montana

- Petroglyphs in Montana

- National Register of Historic Places in Yellowstone County, Montana

- Native American history of Montana