Greater omentum

| Greater omentum | |

|---|---|

The greater omentum and corresponding vasculature is visible covering the intestines (dissection image with liver held out of the way). Label at bottom. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Dorsal mesentery |

| Artery | Right gastro-epiploic artery |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | omentum majus |

| TA98 | A10.1.02.201 |

| TA2 | 3757 |

| FMA | 9580 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

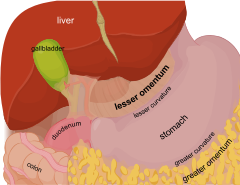

The greater omentum (also the great omentum, omentum majus, gastrocolic omentum, epiploon, or, especially in non-human animals, caul) is a large apron-like fold of visceral peritoneum that hangs down from the stomach. It extends from the greater curvature of the stomach, passing in front of the small intestines and doubles back to ascend to the transverse colon before reaching to the posterior abdominal wall. The greater omentum is larger than the lesser omentum, which hangs down from the liver to the lesser curvature. The common anatomical term "epiploic" derives from "epiploon", from the Greek epipleein, meaning to float or sail on, since the greater omentum appears to float on the surface of the intestines. It is the first structure observed when the abdominal cavity is opened anteriorly (from the front).[1]

Structure

[edit]

The greater omentum is the larger of the two peritoneal folds. It consists of a double sheet of peritoneum, folded on itself so that it has four layers.[2]

The two layers of the greater omentum descend from the greater curvature of the stomach and the beginning of the duodenum.[2] They pass in front of the small intestines, sometimes as low as the pelvis, before turning on themselves, and ascending as far as the transverse colon, where they separate and enclose that part of the intestine.[2]

These individual layers are easily seen in the young, but in the adult they are more or less inseparably blended.

The left border of the greater omentum is continuous with the gastrosplenic ligament; its right border extends as far as the beginning of the duodenum.

The greater omentum is usually thin, and has a perforated appearance. It contains some adipose tissue, which can accumulate considerably in obese people. It is highly vascularised.[3]

Subdivisions

[edit]

The greater omentum is often defined to encompass a variety of structures. Most sources include the following three:[4][5]

- Gastrophrenic ligament—extends to the underside of the left dome of the diaphragm

- Gastrocolic ligament—extends to the transverse colon (occasionally on its own considered synonymous with "greater omentum"[4])

- Gastrosplenic ligament (or Gastrolienal) ligament)— extends to the spleen, overlying the kidney

The splenorenal ligament (or lienorenal ligament) (from the left kidney to the spleen) is occasionally considered part of the greater omentum.[6][7] It is derived from the peritoneum, where the wall of the general peritoneal cavity comes into contact with the lesser sac between the left kidney and the spleen; the splenic artery and vein pass between its two layers. It contains the tail of the pancreas, the only intraperitoneal portion of the pancreas, and splenic vessels.![]() One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

Phrenicosplenic ligament

[edit]The phrenosplenic ligament (lienophrenic ligament or phrenicolienal ligament) is a double fold of peritoneum that connects the thoracic diaphragm and spleen.[8]

The phrenicosplenic ligament is part of the greater omentum. Distinctions between the phrenicosplenic ligament and adjacent ligaments, such as the gastrophrenic, gastrosplenic and splenorenal ligaments, which are all part of the same mesenteric sheet, are often nebulous.[8]

Blood supply

[edit]The right and left gastroepiploic arteries (also known as gastroomental) provide the sole blood supply to the greater omentum. Both are branches of the celiac trunk. The right gastroepiploic artery is a branch of the gastroduodenal artery, which is a branch of the common hepatic artery, which is a branch of the celiac trunk. The left gastroepiploic artery is the largest branch of the splenic artery, which is a branch of the celiac trunk. The right and left gastroepiploic arteries anastomose within the two layers of the anterior greater omentum along the greater curvature of the stomach.

Development

[edit]

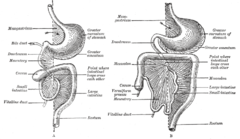

The greater omentum develops from the dorsal mesentery that connects the stomach to the posterior abdominal wall. During its development, the stomach undergoes its first 90° rotation along the axis of the embryo, so that posterior structures are moved to the left and structures anterior to the stomach are shifted to the right. As a result, the dorsal mesentery folds over on itself, forming a pouch with its blind end on the left side of the embryo. A second approximately 90° rotation of the stomach, this time in the frontal plane, moves structures inferior if they were originally to the left of the stomach, and superior if they were originally to the stomach's right. Consequently, the blind-ended sac (also called the lesser sac) formed by the dorsal mesentery is brought inferiorly, where it assumes its final position as the greater omentum. It grows to the point that it covers the majority of the small and large intestine.

Functions

[edit]The functions of the greater omentum are:

- Fat deposition, having varying amounts of adipose tissue[9]

- Immune contribution, having milky spots of macrophage collections[9]

- Infection and wound isolation; It may also physically limit the spread of intraperitoneal infections.[9] The greater omentum can often be found wrapped around areas of infection and trauma.

Clinical significance

[edit]Surgical removal

[edit]Omentectomy refers to the surgical removal of the omentum, a relatively simple procedure with no documented major side effects, that is performed in cases where there is concern that there may be spread of cancerous tissue into the omentum. Examples for this are ovarian cancer and advanced or aggressive endometrial cancer as well as intestinal cancer and also appendix cancer. The procedure is generally done as an add-on when the primary lesion is removed.

Omental flap

[edit]The greater omentum may be surgically harvested for reconstruction of the thoracic wall.[3] It has also been used experimentally to reinforce bioengineered tissues transplanted to the surface of the heart for cardiac regeneration.[10]

Use in brain surgery

[edit]The greater omentum may be surgically harvested to provide revascularization of brain tissue after a stroke.[11]

History

[edit]The greater omentum is also known as the great omentum, the omentum majus, the gastrocolic omentum, the epiploon, and the caul.

In 1906, the greater omentum was described as the "abdominal policeman" by the surgeon James Rutherford Morrison.[12] This is due to its immunological function, whereby omental tissue seems to "surveil" the abdomen for infection and cover areas of infection when found - walling it off with immunologically active tissue.

Additional images

[edit]-

Vertical disposition of the peritoneum. Main cavity, red; omental bursa, blue. (Greater omentum labeled at left.)

-

The greater omentum is attached to the lower portion of the stomach (here the attachment is cut and the stomach is lifted up).

-

The celiac artery and its branches; the liver has been raised, and the lesser omentum and anterior layer of the greater omentum removed.

-

Schematic figure of the bursa omentalis, etc. Human embryo of eight weeks.

-

Diagrams to illustrate the development of the greater omentum and transverse mesocolon.

-

Greater omentum. Deep dissection.

See also

[edit]- Caul fat

- Omental cake

- Omental infarction

- Right gastroepiploic vein

- Omental bursa (Lesser sac)

- Greater sac

- Omental foramen (Epiploic foramen, Foramen of Winslow)

- Lesser omentum

- Peritoneum

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Drake, Richard L., et al., Gray's anatomy for students, Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier, 2010. Print.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Federle, Michael P.; Rosado-de-Christenson, Melissa L.; Woodward, Paula J.; Carter, Brett W.; Raman, Siva P.; Shaaban, Akram M., eds. (2017). "Peritoneal Cavity". Imaging Anatomy: Chest, Abdomen, Pelvis. pp. 528–549. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-47781-9.50027-1. ISBN 978-0-323-47781-9.

- ^ a b Fayanju, Oluwadamilola M.; Garvey, Patrick Bryan; Karuturi, Meghan S.; Hunt, Kelly K.; Bedrosian, Isabelle (2018). "Surgical Procedures for Advanced Local and Regional Malignancies of the Breast". The Breast. pp. 778–801.e4. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-35955-9.00059-3. ISBN 978-0-323-35955-9.

- ^ a b Dalley, Arthur F.; Moore, Keith L. (2006). Clinically oriented anatomy. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 237. ISBN 0-7817-3639-0.

- ^ Anatomy Tables – Stomach & Spleen Archived 2006-12-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kyung Won Chung (2005). Gross Anatomy (Board Review). Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 205. ISBN 0-7817-5309-0.

- ^ "Module - Peritoneal Cavity Development". Archived from the original on 2007-11-13. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ^ a b "Phrenicosplenic ligament". Farlex Partner Medical Dictionary. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ a b c Alagumuthu, M.; Das, Bhupati; Pattanayak, Siba; Rasananda, Mangual (1 May 2006). "The omentum: A unique organ of exceptional versatility". Indian Journal of Surgery. 68 (3): 136–141. Gale A148391067.

- ^ Wang, Hogan; Roche, Christopher D; Gentile, Carmine (1 December 2020). "Omentum support for cardiac regeneration in ischaemic cardiomyopathy models: a systematic scoping review". European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 58 (6): 1118–1129. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezaa205. PMC 7697859. PMID 32808023.

- ^ Kuper, C. Frieke; Ruehl-Fehlert, Christine; Elmore, Susan A.; Parker, George A. (2013). "Immune System". Haschek and Rousseaux's Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology. pp. 1795–1862. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-415759-0.00049-2. ISBN 978-0-12-415759-0.

The omentum helps to restore tissue integrity in the peritoneum by connecting tissue repair with immunological defense. Upon intraperitoneal immunization, follicles and germinal centers can be formed.

- ^ Epstein, Leonard I. (25 September 1967). "The Abdominal Policeman". JAMA. 201 (13): 1054. doi:10.1001/jama.1967.03130130080033.

External links

[edit]- Anatomy figure: 37:03-07 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center [dead link]

- Anatomy figure: 37:05-12 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center [dead link]

- Anatomy photo:37:07-0100 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center [dead link]

- spleen at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)

- abdominalcavity at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (xsectthrulesseromentum)

- Diagram at Tn.edu Archived 2007-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Photo of model at Waynesburg College digirep/greateromentum

- Learn about living without an Omentum at The Omentum Project: https://www.theomentumproject.org/