Phonation

| Part of a series on | ||||||

| Phonetics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Linguistics Series | ||||||

| Subdisciplines | ||||||

| Articulation | ||||||

|

||||||

| Acoustics | ||||||

|

||||||

| Perception | ||||||

|

||||||

| Linguistics portal | ||||||

The term phonation has slightly different meanings depending on the subfield of phonetics. Among some phoneticians, phonation is the process by which the vocal folds produce certain sounds through quasi-periodic vibration. This is the definition used among those who study laryngeal anatomy and physiology and speech production in general. Phoneticians in other subfields, such as linguistic phonetics, call this process voicing, and use the term phonation to refer to any oscillatory state of any part of the larynx that modifies the airstream, of which voicing is just one example. Voiceless and supra-glottal phonations are included under this definition.

Voicing

[edit]The phonatory process, or voicing, occurs when air is expelled from the lungs through the glottis, creating a pressure drop across the larynx. When this drop becomes sufficiently large, the vocal folds start to oscillate. The minimum pressure drop required to achieve phonation is called the phonation threshold pressure (PTP),[1][2] and for humans with normal vocal folds, it is approximately 2–3 cm H2O. The motion of the vocal folds during oscillation is mostly lateral, though there is also some superior component as well. However, there is almost no motion along the length of the vocal folds. The oscillation of the vocal folds serves to modulate the pressure and flow of the air through the larynx, and this modulated airflow is the main component of the sound of most voiced phones.

The sound that the larynx produces is a harmonic series. In other words, it consists of a fundamental tone (called the fundamental frequency, the main acoustic cue for the percept pitch) accompanied by harmonic overtones, which are multiples of the fundamental frequency.[3] According to the source–filter theory, the resulting sound excites the resonance chamber that is the vocal tract to produce the individual speech sounds.

The vocal folds will not oscillate if they are not sufficiently close to one another, are not under sufficient tension or under too much tension, or if the pressure drop across the larynx is not sufficiently large.[4] In linguistics, a phone is called voiceless if there is no phonation during its occurrence.[5] In speech, voiceless phones are associated with vocal folds that are elongated, highly tensed, and placed laterally (abducted) when compared to vocal folds during phonation.[6]

Fundamental frequency, the main acoustic cue for the percept pitch, can be varied through a variety of means. Large scale changes are accomplished by increasing the tension in the vocal folds through contraction of the cricothyroid muscle. Smaller changes in tension can be effected by contraction of the thyroarytenoid muscle or changes in the relative position of the thyroid and cricoid cartilages, as may occur when the larynx is lowered or raised, either volitionally or through movement of the tongue to which the larynx is attached via the hyoid bone.[6] In addition to tension changes, fundamental frequency is also affected by the pressure drop across the larynx, which is mostly affected by the pressure in the lungs, and will also vary with the distance between the vocal folds. Variation in fundamental frequency is used linguistically to produce intonation and tone.

There are currently two main theories as to how vibration of the vocal folds is initiated: the myoelastic theory and the aerodynamic theory.[7] These two theories are not in contention with one another and it is quite possible that both theories are true and operating simultaneously to initiate and maintain vibration. A third theory, the neurochronaxic theory, was in considerable vogue in the 1950s, but has since been largely discredited.

Myoelastic and aerodynamic theory

[edit]The myoelastic theory states that when the vocal cords are brought together and breath pressure is applied to them, the cords remain closed until the pressure beneath them, the subglottic pressure, is sufficient to push them apart, allowing air to escape and reducing the pressure enough for the muscle tension recoil to pull the folds back together again. The pressure builds up once again until the cords are pushed apart, and the whole cycle keeps repeating itself. The rate at which the cords open and close, the number of cycles per second, determines the pitch of the phonation.[8]

The aerodynamic theory is based on the Bernoulli energy law in fluids. The theory states that when a stream of breath is flowing through the glottis while the arytenoid cartilages are held together (by the action of the interarytenoid muscles), a push-pull effect is created on the vocal fold tissues that maintains self-sustained oscillation. The push occurs during glottal opening, when the glottis is convergent, and the pull occurs during glottal closing, when the glottis is divergent.[1] Such an effect causes a transfer of energy from the airflow to the vocal fold tissues which overcomes losses by dissipation and sustain the oscillation.[2] The amount of lung pressure needed to begin phonation is defined by Titze as the oscillation threshold pressure.[1] During glottal closure, the air flow is cut off until breath pressure pushes the folds apart and the flow starts up again, causing the cycles to repeat.[8] The textbook entitled Myoelastic Aerodynamic Theory of Phonation[7] by Ingo Titze credits Janwillem van den Berg as the originator of the theory and provides detailed mathematical development of the theory.

Neurochronaxic theory

[edit]This theory states that the frequency of the vocal fold vibration is determined by the chronaxie of the recurrent nerve, and not by breath pressure or muscular tension. Advocates of this theory thought that every single vibration of the vocal folds was due to an impulse from the recurrent laryngeal nerves and that the acoustic center in the brain regulated the speed of vocal fold vibration.[8] Speech and voice scientists have long since abandoned this theory as the muscles have been shown to not be able to contract fast enough to accomplish the vibration. In addition, persons with paralyzed vocal folds can produce phonation, which would not be possible according to this theory. Phonation occurring in excised larynges would also not be possible according to this theory.

State of the glottis

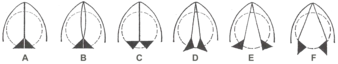

[edit]A. Glottis closure; B. phonation position; C. whisper position; D. breath position; E. respiratory position or resting position; F. deep breathing position

In linguistic phonetic treatments of phonation, such as those of Peter Ladefoged, phonation was considered to be a matter of points on a continuum of tension and closure of the vocal cords. More intricate mechanisms were occasionally described, but they were difficult to investigate, and until recently the state of the glottis and phonation were considered to be nearly synonymous.[9][page needed]

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Modal voice | Regular vibrations of the vocal cords |

| Voiceless | Lack of vibration of the vocal cords; arytenoid cartilages usually apart |

| Aspirated | Having greater airflow than in modal voice before or after a stricture; arytenoid cartilages may be further apart than in voiceless |

| Breathy voice | Vocal cords vibrating but without appreciable contact; arytenoid cartilages further apart than in modal voice |

| Slack voice | Vocal cords vibrating but more loosely than in modal voice |

| Creaky voice | Vocal cords vibrating anteriorly, but with the arytenoid cartilages pressed together; lower airflow than in modal voice |

| Stiff voice | Vocal cords vibrating but more stiffly than in modal voice |

If the vocal cords are completely relaxed, with the arytenoid cartilages apart for maximum airflow, the cords do not vibrate. This is voiceless phonation, and is extremely common with obstruents. If the arytenoids are pressed together for glottal closure, the vocal cords block the airstream, producing stop sounds such as the glottal stop. In between there is a sweet spot of maximum vibration. Also, the existence of an optimal glottal shape for ease of phonation has been shown, at which the lung pressure required to initiate the vocal cord vibration is minimum.[4] This is modal voice, and is the normal state for vowels and sonorants in all the world's languages. However, the aperture of the arytenoid cartilages, and therefore the tension in the vocal cords, is one of degree between the end points of open and closed, and there are several intermediate situations utilized by various languages to make contrasting sounds.[9][page needed]

For example, Gujarati has vowels with a partially lax phonation called breathy voice or murmured voice (transcribed in IPA with a subscript umlaut ◌̤), while Burmese has vowels with a partially tense phonation called creaky voice or laryngealized voice (transcribed in IPA with a subscript tilde ◌̰). The Jalapa dialect of Mazatec is unusual in contrasting both with modal voice in a three-way distinction. (Mazatec is a tonal language, so the glottis is making several tonal distinctions simultaneously with the phonation distinctions.)[9][page needed]

| Mazatec | ||

| breathy voice | [ja̤] | he wears |

| modal voice | [já] | tree |

| creaky voice | [ja̰] | he carries |

- Note: There was an editing error in the source of this information. The latter two translations may have been mixed up.

Javanese does not have modal voice in its stops, but contrasts two other points along the phonation scale, with more moderate departures from modal voice, called slack voice and stiff voice. The "muddy" consonants in Shanghainese are slack voice; they contrast with tenuis and aspirated consonants.[9][page needed]

Although each language may be somewhat different, it is convenient to classify these degrees of phonation into discrete categories. A series of seven alveolar stops, with phonations ranging from an open/lax to a closed/tense glottis, are:

| Open glottis | [t] | voiceless (full airstream) |

| [d̤] | breathy voice | |

| [d̥] | slack voice | |

| Sweet spot | [d] | modal voice (maximum vibration) |

| [d̬] | stiff voice | |

| [d̰] | creaky voice | |

| Closed glottis | [ʔ͡t] | glottal closure (blocked airstream) |

The IPA diacritics under-ring and subscript wedge, commonly called "voiceless" and "voiced", are sometimes added to the symbol for a voiced sound to indicate more lax/open (slack) and tense/closed (stiff) states of the glottis, respectively. (Ironically, adding the 'voicing' diacritic to the symbol for a voiced consonant indicates less modal voicing, not more, because a modally voiced sound is already fully voiced, at its sweet spot, and any further tension in the vocal cords dampens their vibration.)[9][page needed]

Alsatian, like several Germanic languages, has a typologically unusual phonation in its stops. The consonants transcribed /b̥/, /d̥/, /ɡ̊/ (ambiguously called "lenis") are partially voiced: The vocal cords are positioned as for voicing, but do not actually vibrate. That is, they are technically voiceless, but without the open glottis usually associated with voiceless stops. They contrast with both modally voiced /b, d, ɡ/ and modally voiceless /p, t, k/ in French borrowings, as well as aspirated /kʰ/ word initially.[9][page needed]

If the arytenoid cartiledges are parted to admit turbulent airflow, the result is whisper phonation if the vocal folds are adducted, and whispery voice phonation (murmur) if the vocal folds vibrate modally. Whisper phonation is heard in many productions of French oui!, and the "voiceless" vowels of many North American languages are actually whispered.[10]

Glottal consonants

[edit]It has long been noted that in many languages, both phonologically and historically, the glottal consonants [ʔ, ɦ, h] do not behave like other consonants. Phonetically, they have no manner or place of articulation other than the state of the glottis: glottal closure for [ʔ], breathy voice for [ɦ], and open airstream for [h]. Some phoneticians have described these sounds as neither glottal nor consonantal, but instead as instances of pure phonation, at least in many European languages. However, in Semitic languages they do appear to be true glottal consonants.[9][page needed]

Supra-glottal phonation

[edit]In the last few decades it has become apparent that phonation may involve the entire larynx, with as many as six valves and muscles working either independently or together. From the glottis upward, these articulations are:[11]

- glottal (the vocal cords), producing the distinctions described above

- ventricular (the 'false vocal cords', partially covering and damping the glottis)

- arytenoid (sphincteric compression forwards and upwards)

- epiglotto-pharyngeal (retraction of the tongue and epiglottis, potentially closing onto the pharyngeal wall)

- raising or lowering of the entire larynx

- narrowing of the pharynx

Until the development of fiber-optic laryngoscopy, the full involvement of the larynx during speech production was not observable, and the interactions among the six laryngeal articulators is still poorly understood. However, at least two supra-glottal phonations appear to be widespread in the world's languages. These are harsh voice ('ventricular' or 'pressed' voice), which involves overall constriction of the larynx, and faucalized voice ('hollow' or 'yawny' voice), which involves overall expansion of the larynx.[11]

The Bor dialect of Dinka has contrastive modal, breathy, faucalized, and harsh voice in its vowels, as well as three tones. The ad hoc diacritics employed in the literature are a subscript double quotation mark for faucalized voice, [a͈], and underlining for harsh voice, [a̠].[11] Examples are,

| Voice | modal | breathy | harsh | faucalized |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bor Dinka | tɕìt | tɕì̤t | tɕì̠t | tɕì͈t |

| diarrhea | go ahead | scorpions | to swallow |

Other languages with these contrasts are Bai (modal, breathy, and harsh voice), Kabiye (faucalized and harsh voice, previously seen as ±ATR), Somali (breathy and harsh voice).[11]

Elements of laryngeal articulation or phonation may occur widely in the world's languages as phonetic detail even when not phonemically contrastive. For example, simultaneous glottal, ventricular, and arytenoid activity (for something other than epiglottal consonants) has been observed in Tibetan, Korean, Nuuchahnulth, Nlaka'pamux, Thai, Sui, Amis, Pame, Arabic, Tigrinya, Cantonese, and Yi.[11]

European language examples

[edit]In languages such as French and Portuguese, all obstruents occur in pairs, one modally voiced and one voiceless: [b] [d] [g] [v] [z] [ʒ] → [p] [t] [k] [f] [s] [ʃ].

In English, every voiced fricative corresponds to a voiceless one. For the pairs of English stops, however, the distinction is better specified as voice onset time rather than simply voice: In initial position, /b d g/ are only partially voiced (voicing begins during the hold of the consonant), and /p t k/ are aspirated (voicing begins only well after its release). Certain English morphemes have voiced and voiceless allomorphs, such as: the plural, verbal, and possessive endings spelled -s (voiced in kids /kɪdz/ but voiceless in kits /kɪts/), and the past-tense ending spelled -ed (voiced in buzzed /bʌzd/ but voiceless in fished /fɪʃt/).

A few European languages, such as Finnish, have no phonemically voiced obstruents but pairs of long and short consonants instead. Outside Europe, the lack of voicing distinctions is common; indeed, in Australian languages it is nearly universal.

Vocal registers

[edit]Phonology

[edit]In phonology, a register is a combination of tone and vowel phonation into a single phonological parameter. For example, among its vowels, Burmese combines modal voice with low tone, breathy voice with falling tone, creaky voice with high tone, and glottal closure with high tone. These four registers contrast with each other, but no other combination of phonation (modal, breath, creak, closed) and tone (high, low, falling) is found.

Pedagogy and speech pathology

[edit]Among vocal pedagogues and speech pathologists, a vocal register also refers to a particular phonation limited to a particular range of pitch, which possesses a characteristic sound quality.[12] The term "register" may be used for several distinct aspects of the human voice:[8]

- A particular part of the vocal range, such as the upper, middle, or lower registers, which may be bounded by vocal breaks

- A particular phonation

- A resonance area such as chest voice or head voice

- A certain vocal timbre

Four combinations of these elements are identified in speech pathology: the vocal fry register, the modal register, the falsetto register, and the whistle register.

See also

[edit]- Ballistic syllables

- Breathy voice

- Creaky voice

- Faucalized voice

- Harsh voice

- List of language disorders

- List of phonetics topics

- Modal voice

- Slack voice

- Stiff voice

- Strident vowel

- Vocal resonation

- Voice onset time

- Voice organ

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Titze, I.R. (1988). "The physics of small-amplitude oscillation of the vocal folds". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 83 (4): 1536–1552. Bibcode:1988ASAJ...83.1536T. doi:10.1121/1.395910. PMID 3372869.

- ^ a b Lucero, J. C. (1995). "The minimum lung pressure to sustain vocal fold oscillation". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 98 (2): 779–784. Bibcode:1995ASAJ...98..779L. doi:10.1121/1.414354. PMID 7642816. S2CID 24053484.

- ^ The human instrument. Principles of Voice Production, Prentice Hall (currently published by NCVS.org)

- ^ a b Lucero, J. C. (1998). "Optimal glottal configuration for ease of phonation". Journal of Voice. 12 (2): 151–158. doi:10.1016/S0892-1997(98)80034-9. PMID 9649070.

- ^ Greene, Margaret; Lesley Mathieson (2001). The Voice and its Disorders. John Wiley & Sons; 6th Edition. ISBN 978-1-86156-196-1.

- ^ a b Zemlin, Willard (1998). Speech and hearing science : anatomy and physiology. Allyn and Bacon; 4th edition. ISBN 0-13-827437-1.

- ^ a b Titze, I. R. (2006). The Myoelastic Aerodynamic Theory of Phonation, Iowa City:National Center for Voice and Speech, 2006.

- ^ a b c d McKinney, James (1994). The Diagnosis and Correction of Vocal Faults. Genovex Music Group. ISBN 978-1-56593-940-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19815-6.

- ^ Laver (1994). Principles of Phonetics. pp. 189 ff, 296 ff, 344 ff.

- ^ a b c d e Edmondson, Jerold A.; John H. Esling (2005). "The valves of the throat and their functioning in tone, vocal register, and stress: laryngoscopic case studies". Phonology. 23 (2). Cambridge University Press: 157–191. doi:10.1017/S095267570600087X. S2CID 62531440.

- ^ Large, John (February–March 1972). "Towards an Integrated Physiologic-Acoustic Theory of Vocal Registers". The NATS Bulletin. 28: 30–35.

External links

[edit]- States of the Glottis (Esling & Harris, University of Victoria)

- Universität Stuttgart Speech production

- A video showing phonation in action