Phoenix Park

| Phoenix Park | |

|---|---|

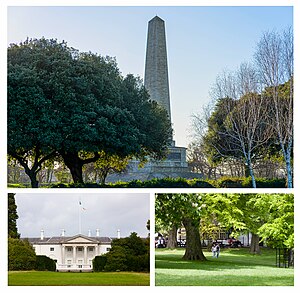

Clockwise from top: the Wellington Monument; gardens near the park's tea rooms; Áras an Uachtaráin, the residence of the president of Ireland | |

| Type | Municipal |

| Location | Dublin, Ireland |

| Coordinates | 53°22′N 6°20′W / 53.36°N 6.33°W |

| Area | 707 hectares (1,750 acres) / 7.07 km2 (2.73 sq mi) |

| Created | 1662 |

| Operated by | Office of Public Works |

| Status | Open all year |

| Website | phoenixpark |

The Phoenix Park (Irish: Páirc an Fhionnuisce[1]) is a large urban park in Dublin, Ireland, lying 2–4 kilometres (1.2–2.5 mi) west of the city centre, north of the River Liffey. Its 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) perimeter wall encloses 707 hectares (1,750 acres) of recreational space.[2][3][4] It includes large areas of grassland and tree-lined avenues, and since the 17th century has been home to a herd of wild fallow deer.[5] The Irish Government is lobbying UNESCO to have the park designated as a World Heritage Site.[6]

History

[edit]

The park's name is derived from the Irish fhionnuisce, meaning clear or still water.[7]

After the Normans conquered Dublin and its hinterland in the 12th century, Hugh Tyrrel, 1st Baron of Castleknock, granted a large area of land, including what now comprises the Phoenix Park, to the Knights Hospitaller. They established an abbey at Kilmainham on the site now occupied by Royal Hospital Kilmainham. The knights lost their lands in 1537 following the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII of England. Eighty years later the lands reverted to the ownership of the King's representatives in Ireland.

On the restoration of Charles II of England, his Viceroy in Dublin, the Duke of Ormond, established a royal hunting park on 2,000 acres (810 ha) of the land in 1662. It contained pheasants and wild deer, making it necessary to enclose the entire area with a wall. The cost of building the park had amounted to £31,000 by 1669.[7]

The park originally included the demesne of Kilmainham Priory south of the River Liffey. When the building of the Royal Hospital at Kilmainham commenced in 1680 for the use of veterans of the Royal Irish Army, the park was reduced to its present size, all of which is now north of the river. It was opened to the people of Dublin by the Earl of Chesterfield in 1745.

In the nineteenth century, the expanse of the park had become neglected. With management being taken over by the Commissioners of Woods and Forests, the renowned English Landscape architect, Decimus Burton, was retained to design an overall plan for the public areas of the park. The execution of the plan, which included new paths, gate-lodges (including the architecturally significant Chapelizod gate lodge [8]), levelling and tree planting, and relocating the Phoenix Column, took almost 20 years to complete. According to the park's official site,

- Burton's involvement for nearly two decades represents the greatest period of landscape change since the Park's creation by the Duke of Ormond.[9]

In 1882, the park was the location for two politically inspired assinations sometimes known as the Phoenix Park Murders. The Chief Secretary for Ireland (the British Cabinet minister with responsibility for Irish affairs), Lord Frederick Cavendish and the Under-Secretary for Ireland (chief civil servant), Thomas Henry Burke, were stabbed to death with surgical knives while walking from Dublin Castle. A small insurgent group called the Irish National Invincibles were responsible.[10]

On 5 August 1933, Oscar Heron, Irish World War I flying ace of the British Royal Air Force, died in an accident at the park whilst taking part in a mock aerial combat for Irish Aviation Day.[11][12]

During the Emergency thousands of tons of turf were transported from the bogs to Dublin and stored in high mounds along the main road of the park.[13][14][15]

In October 2023 the park got its first ever shuttle bus service with the launch of Route 99, connecting the Park's visitor center at Ashford Castle with Parkgate Street just outside the park, near Heuston Station.[16]

Features

[edit]

The park is split between three civil parishes: Castleknock to the northwest, Chapelizod to the south and St James' to the east. The last-named is mainly centred south of the River Liffey around St James' parish church.

Áras an Uachtaráin

[edit]The residence of the president of Ireland, Áras an Uachtaráin, built in 1754, is located in the park. As the Viceregal Lodge, it was the official residence of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland until the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922.

Dublin Zoo

[edit]Dublin Zoo is one of Dublin's main attractions. It houses more than 700 animals and tropical birds from around the world. The Zoological Society of Ireland was established in 1830[17] "to form a collection of animals along the lines of London Zoo". It opened to the public on 1 September 1831 - making it the third oldest zoo in the world - with animals from the London Society. Within a year the zoo housed 123 species.[18]

Papal Cross

[edit]

The Papal Cross at the edge of Fifteen Acres was erected as a backdrop for the outdoor mass celebrated there by Pope John Paul II on 29 September 1979, the first day of his pastoral visit to Ireland. The congregation numbered over one million, equal to Dublin's population. The white Latin cross, which dominates its surroundings, is 35 metres (115 ft) high and was built with steel girders. It was installed with some difficulty: after several attempts, the cross was eventually erected just a fortnight before the Pope arrived.[19] When John Paul died in 2005, devotees gathered at the Papal Cross, praying and leaving flowers and other tokens of remembrance. Pope Francis celebrated mass here on the final day of his 2018 visit to Ireland.

Monuments

[edit]

The Wellington Monument is a 62 metres (203 ft) tall obelisk commemorating the victories of the Duke of Wellington. It is the largest obelisk in Europe and would have been even higher if the publicly subscribed funding had not run out. Designed by Robert Smirke, there are four bronze plaques cast from cannon captured at the Battle of Waterloo—three of which have pictorial representations of Wellington's career while the fourth has an inscription at the base of the obelisk.

A second notable monument is the "Phoenix Column" (shown in the header photograph above), a Corinthian column carved from Portland Stone located centrally on Chesterfield Avenue, the main thoroughfare of the park, at the junction of Acres Road and the Phoenix, the main entrance to Áras an Uachtaráin.[20] A contemporary account described it in the following terms:

"About the centre of the park is a fluted column thirty feet high, with a phoenix on the capital, which was erected by the Earl of Chesterfield during his viceregality."[21] (1747)

There is also a monument to commemorate Lord Cavendish and Thomas Henry Burke, who were killed in the park by the Irish National Invincibles. It is a 60 cm long cross, filled with a small amount of gravel and cut thinly into the grass.[22]

Deerfield Residence

[edit]The Deerfield Residence (previously the Chief Secretary's Lodge), originally built in 1776 was the former residence of the Chief Secretary for Ireland and before that was the Park Bailiff's lodge. It has been the official residence of the United States Ambassador to Ireland since February 1927, and was until the early 1960s the Embassy of the United States in Dublin.[23]

Phoenix Park Visitor Centre and Ashtown Castle

[edit]The oldest building in the park is Ashtown Castle, a restored medieval tower house dating from the 15th century. Restoration began in 1989 and it is located beside the visitor centre which houses interpretive displays on the 5,500 years of park and area history.

People's Gardens

[edit]

The gardens, located close to the Parkgate Street entrance, comprise an area of nine hectares (22 acres), and were re-opened in 1864. These gardens were initially established in 1840 as the Promenade Grounds. They display Victorian horticulture, including ornamental lakes, children's playground, picnic area and bedding schemes. A statue is in the gardens dedicated to executed Easter Rising leader Seán Heuston. There is a plaque in honour of the Irish sculptor Jerome Connor on Infirmary Road, overlooking the gardens which he frequently visited. The opening hours are 8.00 am until dusk. Closing times vary during the year.

Magazine Fort

[edit]

The Magazine Fort in the southeast of the park marks the location where Phoenix Lodge was built by Sir Edward Fisher in 1611. In 1734 the house was demolished when the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Lionel Sackville, 1st Duke of Dorset directed that a powder magazine be provided for Dublin. An additional wing was added to the fort in 1801 for troops. It was the scene of the Christmas Raid in 1939.

The magazine fort has been satirically immortalised in a jingle by Jonathan Swift who wrote:

"Now's here's a proof of Irish sense,

Here Irish wit is seen,

When nothing's left that's worth defence,

We build a Magazine."

Other places of interest

[edit]

- In the southwestern corner of the park is an area known as the Furry Glen which has a series of short walks centred on a small lake with birds, plants and wildlife. The jay, normally a rather shy bird, is common and conspicuous here.

- State Guest House, Farmleigh, adjoins the park to the northwest.

- Headquarters of the Garda Síochána, the police service of Ireland, are located in the park.

- St. Mary's Hospital, originally the Royal Hibernian Military School established in 1769, the building was subsequently developed as a hospital up until 1948. In 1964 the hospital became a facility for older people and today primarily provides accommodation to dependent older persons.[24]

- National Ambulance Service College is located at Saint Mary's Hospital on the Chapelizod side of the park. This building dates from 1766 and was formerly the Hibernian Military School.[25] Ordnance Survey Ireland is located in Mountjoy House near the Castleknock Gate. The house was built in 1728 and was originally known as Mountjoy Barracks as it quartered the mounted escort of the Lord Lieutenant who resided in the Vice-Regal Lodge (now Áras an Uachtaráin).[26]

- Adjoining the park to the southeast is the Irish Defence Forces' McKee Barracks. Built in 1888 as Marlborough Barracks it once housed 822 military horses.[27]

- Ratra House at the back of the Aras, was the home of Civil Defence Ireland since the organisation was established in 1950 until 2006 when the headquarters was decentralised to Roscrea, County Tipperary. Named Ratra House by the first president of Ireland, Douglas Hyde, who retired to the house in 1945 from his presidency. He named it after his native Ratra Park in Frenchpark, County Roscommon where he had done much of his writing. Built in 1876, Winston Churchill lived there from age two to six.[28]

- Grangegorman Military Cemetery lies just outside the walls of the park on Blackhorse Avenue.

- The park also contains several sports grounds for football, hurling, soccer, cricket and polo.

- Bohemian Football Club was founded in the Gate Lodge beside the North Circular Road entrance in 1890. The club played its first games in the park's Polo Grounds.

- At Conyngham Road, near the South Circular Road junction, the regular wall takes on an unusual arch shape before levelling out again. This marks the point where the Liffey Bridge enters the park via a rail tunnel that continues on beneath the Wellington Monument. It is used regularly for goods traffic and Passenger services. It was used during the Second World War for storing emergency supplies of food.[29] Iarnród Éireann opened the tunnel for commuter train traffic on 21 November 2016.[30]

Environment

[edit]

There are 351 identified plant species in the park; three of these are rare and protected. The park has retained almost all of its old grasslands and woodlands and also has rare examples of wetlands.[31] Deer were introduced into the park in the 1660s; the current 400–450 fallow deer descend from the original herd.[31] 30% of the park is covered by trees, mainly broadleaf.

A birdwatch survey in 2007–2008 found 72 species of bird including common buzzard, Eurasian sparrowhawk, common kestrel and Eurasian jay. The great spotted woodpecker, Ireland's newest breeding bird has been seen in the park several times,[32] but no sighting was recorded in 2015,[33] and the long-eared owl has been confirmed as a breeding species in 2012.[34]

The park also holds several brooks, and tributaries of the River Liffey.

In July and August 2006, the Minister for Health and Children, Mary Harney, issued three orders exempting two new community nursing units, to be built at St. Mary's Hospital in the park, from the usual legally required planning permission, despite the Phoenix Park being a designated and protected national monument. A statement from the Department of Health and Children said the decision was made because of what it called the department's "emergency response to the accident and emergency crisis at the time", although the nursing units, in use since 2008, are mainly for geriatric care.[35]

In a 2009 conservative management plan for the park, the Office of Public Works commented, "... the erection, without the necessity of resorting to normal planning procedures, of two major developments in St. Mary's Hospital illustrates the vulnerability of the Phoenix Park to internal development, which impacts significantly on the essential character of the park and its unique value as a historic designed landscape." In a section entitled Pressures and Threats on the Park, subsection Planning Issues, the document expressed concern that, "Without appropriate planning designation, there is a risk that development can take place which is not in line with the co-ordinated vision of this Plan." The document warned of similar risks to the integrity of the park such as "uncoordinated building and construction...and the current condition of certain historic buildings such as the Magazine Fort, the farm buildings below St. Mary's Hospital and Mountjoy House in the Ordnance Survey Complex."[20]

On 18 July 2022, a weather station in the park set a new record high temperature for July in Ireland of 33.0 °C.

Events

[edit]Motor racing

[edit]

Motor racing first took place in the park in 1903 when the Irish Gordon Bennett Race Speed Trials were held on the main straight for both cars and motorcycles. This was followed in 1929 by the Irish International Grand Prix; the first of three Irish motor racing Grand Prix.[36] Racing took place from 1932 until the beginning of the Second World War in 1939 and was revived again in 1949 with a sprint on the Oldtown circuit[37] followed the next year by a full racing meeting again and has been used virtually continuously until today. Over the years seven different circuits have been used, two of which are named after the famous Ferrari World Champion racing driver Mike Hawthorn.

Phoenix Park Motor Races

[edit]After the Grand Prix events, motor racing continued at the park through the 1980s and 1990s and up to 2012, with many events broadcast live on RTÉ. It featured many drivers including Eddie Jordan, Eddie Irvine and Tommy Byrne.

Great Ireland Run

[edit]The Great Ireland Run, a 10 km running competition, has been held annually each April in the park since 2003. It includes races for professional runners and the public and the 2010 edition attracted over 11,000 participants.[38][39] Athletes such as Sonia O'Sullivan and Catherina McKiernan are among the race's past winners.

Concerts

[edit]Music concerts have been performed in the park by such acts as Coldplay, Duran Duran, Robbie Williams, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Ian Brown, Justice, Kanye West, Arcade Fire, Tom Waits, Snow Patrol, Florence and the Machine, Swedish House Mafia, Snoop Dogg, Tinie Tempah, Calvin Harris, the Stone Roses and Ed Sheeran.

Phoenix Park free festivals

[edit]Ubi Dwyer organised one-day free events between 1977 and 1980.[40] As International Times reported "The Hollow in the Phoenix Park spun and danced to the rhythms of the World Peace Band, Free Booze, the Mod Quad Band, Frazzle, Speed, Stryder, Axis, Tudd, Skates to name but a few. The whole thing was organised by gentle Ubi Dwyer who was formerly involved in the Windsor affair of rock and the rest in England. Certainly, the Irish version was pleasantly good-humoured even if the amplification was too much for squares. A few chappies near the bandstand almost whipped themselves to death with their long hair as they responded to the bio-rhythms of the scene."[41] U2 played at the 1978 festival.[42]

Phoenix Cricket Club

[edit]Phoenix Cricket Club is the oldest cricket club in Ireland. Founded in 1830 by John Parnell, the father of Charles Stewart Parnell, the club is located in the park.

Exhibition

[edit]In April 2017 the Hearsum Collection, in collaboration with The Royal Parks of London and Ireland's Office of Public Works, mounted an exhibition at Dublin's Phoenix Park entitled Parks, Our Shared Heritage: The Phoenix Park, Dublin & The Royal Parks, London, demonstrating the historical links between Richmond Park (and other Royal Parks in London) and Phoenix Park.[43] This exhibition was also displayed at the Mall Galleries in London in July and August 2017.[44]

Popular culture

[edit]

The park is featured prominently in James Joyce's novel Finnegans Wake and tangentially in Ulysses.

In general, Dublin postal districts on the Northside are odd numbers, while Southside codes are even. One exception is the Phoenix Park, which is on the Northside but forms part of even-numbered districts, the majority of which is in Dublin 8, and also includes an area bordering Chapelizod in the South-West that falls under the Dublin 20 postcode between the Chapelizod and Knockmaroon Gate Lodges (encompassing the St Mary's Campus).[45][46]

Park rangers

[edit]The park has its own piece of legislation the Phoenix Park Act, 1925 which includes giving powers to park rangers to remove and arrest of offenders who disobey its bye-laws, which include "No person shall act contrary to public morality in the park".[47][48]

Chief rangers of the park have included:

- Marcus Trevor, 1st Viscount Dungannon (1668–1669)

- Thomas Coningsby, 1st Earl Coningsby (1696–1702)

- Henry Petty, 1st Earl of Shelburne (1698–1751) (joint)

- George Germain, 1st Viscount Sackville (1736–1785) (joint)

- John Ligonier, 1st Earl Ligonier (1734–1750)[49]

- Nathaniel Clements (1751–1777)

- James Trail (1806–1808)

- Sir Charles Saxton, 2nd Baronet (1808–1812)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Phoenix Park". logainm.ie. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ^ "Phoenix Park | The Office of Public Works". PhoenixPark.ie. Office of Public Works. 2018. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ "About – Phoenix Park". Office of Public Works. Archived from the original on 7 March 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ "Phoenix Park". Ordnance Survey Ireland. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ^ Joyce, Weston St. John (1921). The Neighbourhood of Dublin (PDF). Dublin: M H Gill & Son. p. 416. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ^ "Secret history of the Phoenix Park". Irish Independent. 19 January 2012. Archived from the original on 5 February 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ^ a b Bennett 2005, p. 191.

- ^ "Chapelizod Gate Lodge, Phoenix Park". Dublin. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018. [accessed 2018.12.05]

- ^ "Phoenix Park: History from the Georgian Period to the Present. The Nineteenth Century and the Decimus Burton Era". Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Roundell, Julia (July–December 1906). The Nineteenth Century and After: Volume 60. London: Spottiswoode & Co. pp. 559–575. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

From A Diary at Dublin Castle during the Phoenix Park Trial

- ^ "Oscar Heron". theaerodrome.com. theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ "September 7 – Veteran hero of Bomber Command. Roll of Honour". remembranceni.org. remembranceni.org. 7 September 2024. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ "A farewell to the old sod". Irish Independent. 9 March 2012. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ Corcoran, Tony (2009). The Goodness of Guinness: A Loving History of the Brewery, Its People, and ... New York: Skyhorse Publishing Inc. p. 83. ISBN 9781602396531. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ Gill-Cummins, Maureen (2012). "Early Days: The Kildare Scheme and the Turf Camps". Taken from Scéal na Móna, Vol. 13, no. 60, December 2006, p70-72. Bord na Móna. Archived from the original on 20 November 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ "First ever public bus service to the Phoenix Park set to launch". Transport for Ireland. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ "About the Zoo – Zoo History". Dublin Zoo. Archived from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ^ Kilfeather, Siobhán Marie (2005). Dublin: a cultural history. Oxford University Press. pp. 115–116. ISBN 0-19-518201-4. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ "Sights of the Park". Office of Public Works. Archived from the original on 29 August 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ a b "The Phoenix Park: Conservative Management Plan: Consultation Draft March 2009" (PDF). Office of Public Works. March 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ An Accurate Observer, "Reminiscences of Half a Century", published in London (1838)

- ^ "An Irishman's Diary: Finding the memorial to the victims of the Invincibles". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ "Ambassador's residence". Embassy of the United States: Dublin – Ireland. Archived from the original on 14 August 2010. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link); [1] Archived 20 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine - ^ St. Mary's Hospital

- ^ "Ordnance Survey Ireland: A Brief History". Ordnance Survey Ireland. Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ "McKee Barracks". Dublin City Council. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ "Ratra House – A Brief History". Civil Defence Ireland. Archived from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ^ Oram, Hugh. "An Irishman's Diary: The Phoenix Park rail tunnel". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ "Train services to start using Phoenix Park tunnel next week". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ^ a b "Nature and Biodiversity | Phoenix Park". Office of Public Works. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ The Birds of Phoenix Park County Dublin Birdwatch Ireland (PDF) (Report). March 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011.

- ^ The Birds of the Phoenix Park, County Dublin: Results of a Repeat Breeding Bird Survey in 2015 (PDF). PhoenixPark.ie (Report). June 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 July 2020 – via Wayback Machine.

- ^ Irish Examiner, 27 February 2012

- ^ "Harney exempted Phoenix Park plan". The Irish Times. 5 May 2009. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ^ PhoenixParkMotorRaces.org The Event. Retrieved 7 March 2007.

- ^ Phoenix Park race tracks Archived 25 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 7 March 2007.

- ^ "Great day for a run as 11,000 take over park". Irish Independent. 19 April 2010. Archived from the original on 22 April 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Race History". Great Ireland Run. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Ubi Dwyer has started a "Legalise it" campaign in Ireland". International Times. 1 January 1980. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "Peace Fest - Ubi Shines Up His Shillelagh". International Times. 1 August 1977. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ "Bill Ubi Dwyer obituary". www.ukrockfestivals.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ Fionnuala Fallon (1 April 2017). "Park yourself in Dublin's finest garden". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ^ "Parks – Our Shared Heritage". London: The Mall Galleries. July 2017. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ "Knockmaroon Gate Lodge" (Map). Google Maps.

- ^ "Phoenix Park Community Nursing Units". HIQA.ie. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "Phoenix Park Bye Laws". Office of Public Works. Archived from the original on 10 January 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ^ "Phoenix Park Act". Office of Public Works. Archived from the original on 9 January 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ^ Hayes, Melanie. "An Irish Palladian in England: the case of Sir Edward Lovett Pearce" (PDF). Retrieved 1 March 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Bennett, Douglas (2005). The Encyclopaedia of Dublin. Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-717-13684-1.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Architecture of key park buildings

- Map of greater Dublin showing the placement and size of the Phoenix Park. It is the large green area west of the city centre.

- Irish Grand Prix, 1929 Pathé News video

- Phoenix Park Act, 1925

- Satellite Photo of the Phoenix Park

- Exhibition: Parks Our shared Heritage: Phoenix Park, Dublin - Royal Parks, London [2]