Phoenice Libanensis

Phoenice Libanensis (Greek: Φοινίκη Λιβανησία, lit. 'Lebanese Phoenicia', also known in Latin as Phoenice Libani, or Phoenice II/Phoenice Secunda), was a province of the Roman Empire, covering the Anti-Lebanon Mountains and the territories to the east, all the way to Palmyra. It was officially created c. 394, when the Roman province of Phoenice was divided into Phoenice proper or Phoenice Paralia, and Phoenice Libanensis, a division that persisted until the region was conquered by the Muslim Arabs in the 630s.

| Phoenice Libanensis Φοινίκη Λιβανησία | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province of the Byzantine Empire | |||||||||||||

| c. 394–635 | |||||||||||||

Page from the Notitia Dignitatum showing the area of the province of Phoenice Libanensis. | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Emesa | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late Antiquity | ||||||||||||

• Created during the reign of Theodosius the Great | c. 394 | ||||||||||||

| 635 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Syria Lebanon | ||||||||||||

Toponymy

[edit]Agapius of Hierapolis used the term “wilderness of Phoenicia” to refer to the steppe between Emesa and Palmyra, in the former province of Lebanese Phoenicia. During the Crusades, William of Tyre and Jacques of Vitry mention Lebanese Phoenicia in its Graeco-Roman borders and limits, undoubtedly based on the administrative and ecclesiastical geographies still known in the Roman Empire.[1][2] William of Tyre goes on to call Damascus the “metropolis of Little Syria, otherwise called Lebanese Phoenicia”.

Under the Ottoman Empire, the former province of the Lebanese Phoenicia was present only in titles used by local Rûm Christians of the Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East. In the list of episcopal titles, for instance, the Archbishops of Emesa, Baalbek, and Palmyra are “exarchos over the whole of Lebanese Phoenicia”.[3][4]

History

[edit]Phoenice I and Phoenice Libanensis

[edit]

The province of Augusta Libanensis, mentioned in the Verona List, was short-lived, but formed the basis of the re-division of Phoenice c. 400 into the Phoenice I or Phoenice Paralia (Greek: Φοινίκη Παραλία, "coastal Phoenice"), and Phoenice II or Phoenice Libanensis (Φοινίκη Λιβανησία), with Tyre and Emesa as their respective capitals.[5] In the Notitia Dignitatum, written shortly after the division, Phoenice I is governed by a consularis, while Libanensis is governed by a praeses, with both provinces under the Diocese of the East.[6] This division remained intact until the Muslim conquest of the Levant in the 630s.[7] Under the Caliphate, most of the two Phoenices came under the province of Damascus, with parts in the south and north going to the provinces of Jordan and Emesa respectively.[8]

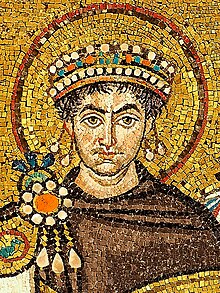

Edicts of Justinian the Great

[edit]Due to mass administrative reforms and edicts directed at Phoenice Libanensis with the goal of preventing further pro-Sassanid raids and invasions, the province was now ruled by two ducēs during the reign of Justinian I.[9][10]

In the edict dating from c.535–539 of Justinian the Great on the province of Phoenice Libanensis, the emperor demanded that the governor restrain the ‘powerful households’, as he declared that the lawlessness of such regions' magnates made him "feel too embarrassed even to speak of the enormity of these people’s errant behaviour, and of how they have bodyguards protecting them and an intolerable number of people behind them, all committing barefaced banditry."[11] In October 527, Justinian’s reorganization of the military administration of Phoenicia Libanensis began, due to the pro-Sassanid Arab raids on the territory. This was amongst his first acts after taking the Byzantine throne. He added a duke (Latin: dux) to the one already established there, causing the province to have two dukes, although the seat of the new duke isn't mentioned in sources. The emperor also ordered the newly appointed comes Orientis, Patricius, to reconstruct Palmyra, its churches, and its baths, and stationed a numerus and a number of limitane there. On the basis of this and of a passage in Procopius, scholars have concluded that the new dux was stationed in Palmyra.

These reforms were due to the devastating raids that were led by the Lakhmid Al-Mundhir during Justin's reign, such raids have reached deep into Oriens, most especially the invasion as far as Emesa in 527. This raid affecting Lebanese Phoenicia probably inspired Justinian's measures. Justinian had the defense of Jerusalem in mind, expecting the dux in Phoenicia to protect the Holy City. Mundhir's raid as far as the Holy Land must have made the Roman authorities apprehensive about the safety of Palestine, and seeing that Mundir had taken a route from Palmyra to Emesa and Apamea. Byzantium wanted to protect the interior of Oriens by intercepting Mundir at Palmyra to prevent him from penetrating deeper into Roman territory. It also seems that the number of phylarchs (pro-Roman Arab sheikhs) assigned to Phoenicia was also raised to two or more. In the edict on the province of 536, more than one phylarch is referred to. In 528 three Arab phylarchs took part in the punitive expedition against Mundhir, and dukes from Phoenicia also participated. Two of the phylarchs named by John Malalas; Naaman and Jafna, may have been appointed to the newly reorganized province.

Palmyra was the last place Justinian fortified in his enormous building program all over the empire, largely for military reasons, other reasons for such building program in the region may have to do with biblical references, as Malalas refers to the biblical association of Palmyra with Solomon, the Old Testament king whom Justinian claimed to have surpassed in the building of Hagia Sophia. In the mid-530s Justinian initiated a wide-ranging program of administrative reforms in the eastern provinces, which included Phoenicia Libanensis.[12]

Edict 4

[edit]The "Edict 4" was issued in May 536 towards Phoenice Libanensis. The edict's main concern was: the assertion of the power of the civil governor over the military and his elevation from praeses to moderator with the higher rank of spectabilis. This edict was for establishing federate and Phylarchal presence in Phoenicia Libanensis. This sole reference to the Arab phylarchs in this province firmly establishes their presence in Phoenicia Libanensis. There's also a reference to phylarchs in the plural, in keeping with the fact that this was a large and exposed province containing desert regions, which explains the assigning of more than one phylarch to it. This text gives the phylarchs their correct rank in the Byzantine system of honors (clarissimus). In contrast to the phylarch of Arabia, al-Harith ibn Jabalah, who was spectabilis, these in Lebanon were ordinary phylarchs, inferior in rank to the spectabilis dux. The more distinguished phylarchs had the higher ranks that appear in Greek inscriptions. The phylarchs mentioned in the edict were subordinate to the dukes of the province, the tribal affiliation of these phylarchs was possibly Ghassanid.

Procopius tells the story of the Strata dispute between al-Harith and Mundir, which served as Persia's pretext for the outbreak of the second Persian war with Byzantium. This account documents the Ghassanids' involvement with Phoenicia, as according to Procopius the Strata was south of Palmyra. In such an important border dispute it was al-Harith the archphylarch, not the lesser phylarchs of Phoenicia, that was involved, showing the archphylarch's transprovincial jurisdiction. Here it was al-Harith, not the dukes, who was the defender of the Roman limes, confirming the view that it was to the Ghassanids (and not the dukes) that the defense of the oriental limes sector from Palmyra to Ayla was primarily left. In his account of the Ghassanids' buildings, the Islamic author Hamza states, in his Arabic chronicle, that there was a Ghassanid presence in Tadmur (Palmyra). This seems confirmed by the explanation of Justinian's edict on Phoenicia. With Palmyra being the seat of one of the two dukes of this province.[12]

Lakhmid raids

[edit]The supreme phylarch al-Harith appears everywhere in Oriens defending Byzantine interests. After three years of the Saracen invasion of 536, al-Harith contested Mundir's claim to the Strata (south of Palmyra in Phoenicia Libanensis), and eighteen years later in June 554 he marched as far as Chalcis in Syria Prima to counter Mundir's invasion of Byzantine territory, leading a battle that led to Mundir's death, the day the battle took place is titled in Arabic: يَوْم حَلِيمَة, romanized: Yawm Ḥalimah, lit. 'Day of Halima'.[12]

Byzantine-Sassanian War and its aftermath

[edit]

During the frequent Roman–Persian Wars that lasted for many centuries, Emesa fell in 613 to Shahrbaraz and was in Sasanian hands until near the end of the war.[13] The Sassanid Persians occupied Phoenice Libanensis alongside the entirety of the Levant from 619 to 629.[14] Shortly after the Byzantine victory in the war and the recovery of the region,[a] it was again lost, this time permanently, to the Muslim conquests: by the 640s, the Muslim Arabs conquered Syria soon after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, establishing a new regime to replace the Romans.[15]

Regions

[edit]The Lebanese Phoenicia was between Heliopolis (Baalbek) and Palmyra, also covering the Anti-Lebanon, Damascus, and Emesa,[16] the regions of the province of Phoenice Libanensis (in southern Syria) mentioned in the Notitia Dignitatum were: Otthara (Al-Gunthor, east of the Hermel),[17] Euhara, Saltatha (possibly Sadad), Lataui, Agatha, Nazala, Abina, Casama (Nabk), Calamona (In Jabal Qalamoun), Betproclis (Bir el-Fourqlous), Thelseae (possibly Doumeir), Adatna (possibly Ḥadata), and Palmira.[18] During the Arab pre-islamic period, in Phoenice Libanensis, Jalliq, the second capital of the Ghassanid Arabs, constituted a major urban center for the Arab population.[19]

Military

[edit]| Dux Foenicis | |

|---|---|

| Active | 4th century-6th century |

| Country | Roman empire |

The Dux Foenicis was a military unit that was in command of the limitanei of Phoenice in its east (Phoenice Libanensis), and of all the forces and fortifications along the desert frontier, including the stretch of the Strata Diocletiana between just north of Palmyra and just south of Damascus. A Dux Phoenices was involved in the war with Mavia's Saracens in c. 377, fighting alongside the Magister Equitum per Orientem.[20] The following units or detachments of units, and prefects and their units, are listed as being under the command of the Dux Foenicis:[21]

| Unit | Location |

|---|---|

| Equites Mauri Illyriciani | Otthara |

| Equites scutarii Illyriciani | Euhari |

| Equites promoti indigenae | Saltatha |

| Equites Dalmati Illyriciani | Latavi |

| Equites promoti indigenae | Avatha |

| Equites promoti indigenae | Nazala |

| Equites sagittarii indigenae | Abina |

| Equites sagittarii indigenae | Casawa |

| Equites sagittarii indigenae | Calamona |

| Equites Saraceni indigenae | Betproclis |

| Equites Saraceni | Thelsee |

| Equites sagittarii indigenae | Adatha |

| Praefectus legionis primae Illyriciorum | Palmira |

| Praefectus legionis tertiae Gallicae | Danaba |

Units from a lesser register include:

| Unit | Location |

|---|---|

| Ala prima Damascena | Monte Iovis |

| Ala nova Diocletiana | Veriaraca |

| Ala prima Francorum | Cunna |

| Ala prima Alamannorum | Neia |

| Ala prima Saxonum | Verofabula |

| Ala prima Foenicum | Rene |

| Ala secunda Salutis | Arefa |

| Cohors tertia Herculia | Veranoca |

| Cohors quinta pacta Alamannorum | Onevatha |

| Cohors prima Iulia lectorum | Vale Alba |

| Cohors secunda Aegyptiorum | Valle Diocletiana |

| Cohors prima Orientalis | Thama |

Ecclesiastical administration

[edit]

The ecclesiastical administration paralleled the political, but with some differences. When the province was divided c. 394, Damascus, rather than Emesa, became the metropolis of Phoenice II. The province belonged to the Patriarchate of Antioch, with Damascus initially outranking Tyre, the capital of Phoenice I, whose position was also briefly challenged by the see of Berytus c. 450; after 480/1, however, the Metropolitan of Tyre established himself as the first in precedence (protothronos) of all the Metropolitans subject to Antioch.[7] In February 452[b] the alleged head of John the Baptist was discovered in the monastery of Spelaion, in the diocese of Emesa, in Phoenice II.[23] Following this event, Emesa—which had first been a suffragan of Damascus[24]—was "probably raised to the rank of honorary [ecclesiastical] metropolis of Lebanese Phoenicia in the second half of the fifth century" according to Julien Aliquot.[9]

This situation, "conforming to the letter of the twelfth canon of the Council of Chalcedon", continued at least until around 570, when the Notitia Antiochena[9] was first written. According to Julien Aliquot: "The subsequent alterations of the Notitia Antiochena attest, however, that the city became an ecclesiastical metropolis in the full sense of the term between the end of the VI century and the beginning of the VII century and that it was given its own jurisdiction, comprising the four bishoprics of Arka, Maurikopolis, Armenia and Stéphanoupolis"[25] This was probably due, according to Julien Aliquot, to the transfer of the head of John the Baptist to the city of Emessa from the monastery of Spelaion attested by Theophanes the Confessor, although it is dated by him to around the year 760 – "more than a century after the Muslim conquest of the Near East" – which is an unlikely date.[26]

It's presumed that Julian of Emesa was considered as the patron saint of Phoenice Libanensis. The Notitia Antiochena, composed about 570, lists eleven bishoprics of Phoenicia Libanensis under the metropolitan of Damascus, among which it lists the “bishopric of Euhara” and the “bishopric of the Saracens.”[27]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ It's unknown if the province kept its name after the Byzantine reconquest.

- ^ Vitalien Laurent suggested the month of February 453[22]

References

[edit]- ^ William of Tyre, Histoire des Croisades, available from [1]

- ^ Jacques of Vitry, Histoire des Croisades, Available from: [2]

- ^ Charon, C., 1907. La hiérarchie melkite du patriarcat d'Antioche, in: Échos d'Orient, tome 10, n°65, pp.223–230. Doi: [3]

- ^ Rustum, A., 1988. Kanisat Madinat Allah Antakia el Ouzma [The Church of the City of God, Great Antioch], Volume I, Éditions de la Librairie Saint-Paul, Beirut, Lebanon, p. 61-62

- ^ Eißfeldt 1941, pp. 368–369.

- ^ Notitia Dignitatum, in partibus Orientis, I

- ^ a b Eißfeldt 1941, p. 369.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 47–48, 240.

- ^ a b c Julien Aliquot, p. 126.

- ^ Trombley, Frank. "The Operational Methods of the Late Roman Army in the Persian War of 572–591".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Mayerson, Philip (1988). "Justinian's Novel 103 and the Reorganization of Palestine". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (269): 65–71. doi:10.2307/1356951. ISSN 0003-097X.

- ^ a b c Shahîd, Irfan (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Volume 1, Part 1, Political and Military History. Dumbarton Oaks. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University.

- ^ Crawford, Peter (2013). The War of the Three Gods: Romans, Persians and the Rise of Islam. Pen and Sword. pp. 42–43. ISBN 9781473828650.

- ^ M., Page, Melvin E., 1944- Sonnenburg, Penny (2003). Colonialism : an international social, cultural, and political encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. OCLC 773516651.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Giftopoulou, Sofia (2005). "Diocese of Oriens (Byzantium)". Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor. Foundation of the Hellenic World. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ^ Rustum, A., 1988. Kanisat Madinat Allah Antakia el Ouzma [The Church of the City of God, Great Antioch], Volume I, Éditions de la Librairie Saint-Paul, Beirut, Lebanon, p 399.

- ^ Brown, J. P.; Gatier, P.-L. (2017-05-12). "Otthara: a Pleiades place resource". Pleiades: a gazetteer of past places. DARMC, R. Talbert, R. Warner, Jeffrey Becker, Sean Gillies, Tom Elliott. Retrieved 2022-11-12.

- ^ Dussaud, René (2015-03-16), "Chapitre V. Palmyre et la Damascène", Topographie historique de la Syrie antique et médiévale, Bibliothèque archéologique et historique, Beyrouth: Presses de l’Ifpo, pp. 247–322, ISBN 978-2-35159-464-3, retrieved 2022-11-12

- ^ Byzantium and the Arabs in the sixth century, Irfan Shahîd, p. 358.

- ^ ND

- ^ ND

- ^ Vitalien Laurent, Le corpus des sceaux de l'empire byzantin, t. 5 : L'Église, Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 1965, p. 380.

- ^ Julien Aliquot, p. 122.

- ^ Siméon Vailhé, p. 142.

- ^ Julien Aliquot, p. 126.

- ^ Julien Aliquot, p. 127.

- ^ Shahîd, Irfan (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Volume 1, Part 2, Ecclesiastical History. Dumbarton Oaks. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University.

Sources

[edit]- Julien Aliquot, Culte des saints et rivalités civiques en Phénicie à l'époque protobyzantine, from Des dieux civiques aux saints patrons, Read online

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihâd State: The Reign of Hishām ibn ʻAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1827-7.

- Eißfeldt, Otto (1941). "Phoiniker (Phoinike)". Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft. Vol. Band XX, Halbband 39, Philon–Pignus. pp. 350–379.