Serbophilia

Appearance

(Redirected from Philo-Serbianism)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

| Part of a series on |

| Serbs |

|---|

|

Serbophilia (Serbian: Србофилија, romanized: Srbofilija, literally love for Serbia and Serbs) is the admiration, appreciation or emulation of non-Serbian person who expresses a strong interest, positive predisposition or appreciation for the Serbian people, Serbia, Republika Srpska, Serbian language, culture or history. Its opposite is Serbophobia.

History

20th century

World War I

During World War I, Serbophilia was present in western countries.[1]

Breakup of Yugoslavia

Political scientist Sabrina P. Ramet writes that Serbophilia in France during the 1990s was "traditional", partly as a response to the closeness between Germany and Croatia. Business ties continued during the war and fostered a desire for economic normalization.[2]

Serbophiles

- Jacob Grimm — German philologist, jurist and mythologist. Learnt Serbian in order to read Serbian epic poetry.[3][4]

- Archibald Reiss — German-Swiss publicist, chemist, forensic scientist, a professor at the University of Lausanne.[5]

- Victor Hugo — French poet, novelist, and dramatist of the Romantic movement. Hugo wrote the speech Pour la Serbie.[citation needed]

- Alphonse de Lamartine — French author, poet, and statesman.[6][7]

- Helen of Anjou — French noblewoman who became queen consort of the Serbian Kingdom.[citation needed]

- Mircea I and Vlad III Dracula[8]

- Several notable composers used motifs from Serbian folk music and composed works inspired by Serbian history or culture, such as:

- Johannes Brahms— German composer, pianist, and conductor of the Romantic period.[9][page needed]

- Franz Liszt — Hungarian composer, virtuoso pianist, conductor, music teacher, arranger, and organist of the Romantic era.[9][page needed]

- Arthur Rubinstein — Polish-American classical pianist.[9][page needed]

- Antonín Dvořák — Czech composer, one of the first to achieve worldwide recognition.[9][page needed]

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky — Russian composer of the Romantic period (See Serbo-Russian March).[9][page needed]

- Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov — Russian composer, and a member of the group of composers known as The Five (See Fantasy on Serbian Themes).[9][page needed]

- Franz Schubert — Austrian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras.[9][page needed]

- Hans Huber — Swiss composer. Between 1894 and 1918, he composed five operas.[9][page needed]

- Rebecca West (1892–1983) — British travel writer. Was described by American media as having a pro-Serbian stance.[10][11]

- Flora Sandes — British Irish volunteer in World War I.[11]

- Ruth Mitchell — American volunteer in the Chetniks, World War II. Sister of Billy Mitchell.[12][13][14]

- Robert De Niro— American actor[15]

- John Challis— English actor best known for portraying Terrance Aubrey "Boycie" Boyce in the BBC Television sitcom Only Fools and Horses (1981–2003) and its sequel/spin-off The Green Green Grass (2005–2009) [16]

- Peter Handke — Austrian novelist and playwright, Nobel Prize winner. Supported Serbia in the Yugoslav Wars.[17]

- Eduard Limonov — Russian writer and poet.[18][19]

- Ángel Pulido — Spanish physician, publicist and politician, who stood out as prominent philosephardite during the Restoration [20][failed verification]

- Essad Pasha Toptani — Ottoman Albanian politician.[21]

- Anna Dandolo— Venetian noblewoman who became Queen of Serbia.[22]

- Józef Bartłomiej Zimorowic — Polish poet and historian of the Baroque era.[23][failed verification]

- Adam Jerzy Czartoryski — Polish nobleman, statesman, diplomat and author.[citation needed]

- Pavel Jozef Šafárik — Slovakian philologist, poet, literary historian, historian and ethnographer in the Kingdom of Hungary. He was one of the first scientific Slavistics.[citation needed]

- Ján Kollár — Slovakian writer (mainly poet), archaeologist, scientist, politician, and main ideologist of Pan-Slavism.[citation needed]

- Ľudovít Štúr — Slovakian revolutionary politician and writer.[citation needed]

- Henry Bax-Ironside — British diplomat.[24]

- Eleftherios Venizelos — Greek statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movement.[citation needed]

- Dimitrios Karatasos — Greek armatolos who participated in the Greek War of Independence, and several other rebellions, seeking to liberate his native Greek Macedonia.[25]

- Herbert Vivian — British journalist and author of Servia: The Poor Man's Paradise and The Servian Tragedy: With Some Impressions of Macedonia.[26]

- Alexander Kolchak — Imperial Russian admiral, military leader and polar explorer.[27]

- Yu Hua — Chinese author.[28]

- František Zach — Czech soldier and military theorist.[29]

Gallery

-

"A Threatening Situation", a comic published in the American newspaper the Brooklyn Eagle in July 1914

-

Departure for Serbia

-

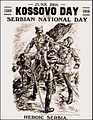

WWI poster - Kosovo Day, June 28, 1916, published in solidarity with the Serb allies

-

WWI poster - Save Serbia (1915)

-

American poster of the Serbian Relief Fund, organised by Mabel Grouitch, asking for donations to help Serbia on the brink of famine.

See also

References

- ^ Dobbs, Michael (11 June 2000). "Blood Bath". Washington Post.

- ^ Ramet, Sabrina P. (2018). Balkan Babel: The Disintegration Of Yugoslavia From The Death Of Tito To The Fall Of Milosevic (Fourth ed.). Routledge. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-42997-503-5.

- ^ Donald Haase (2008). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales: G-P. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 531–. ISBN 978-0-313-33443-6.

- ^ Selvelli, Giustina. "The Cultural Collaboration between Jacob Grimm and Vuk Karadžić. A fruitful Friendship Connecting Western Europe to the Balkans".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Boskovska, Nada (2017). Yugoslavia and Macedonia Before Tito: Between Repression and Integration. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-78673-073-2.

- ^ Mićunović, Milica (28 November 2012). "How Serbia stunned Alphonse de Lamartine". Serbia.com.

- ^ Maric, Natasa (19 March 2021). "Pourquoi la Serbie aime tant la France et la langue française". lefigaro.fr.

- ^ Ion Pătroiu (1987). Marele Mircea Voievod. Editura Academiei Repubvlicii Socialiste România. p. 460.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tomić 2019.

- ^ Victoria Glendinning (1988). Rebecca West: A Life. Fawcett Columbine. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-449-90320-9.

- ^ a b Hammond, Andrew (2010). "Memoirs of conflict: British women travellers in the Balkans". Studies in Travel Writing. 14 (1): 70. doi:10.1080/13645140903465043. S2CID 162162690.

- ^ "War". The Atlantic. Atlantic Monthly Company. 1946. p. 184.

There are also certain American Serbophiles who will hear no evil of Mihailovich, and who repudiate as Communist-inspired any suggestion that he ever collaborated with the enemy. Ruth Mitchell, author of The Serbs Choose War, is one of them.

- ^ Kurapovna, Marcia.Shadows on the Mountain: The Allies, the Resistance, and the Rivalries that Doomed WWII Yugoslavia. John Wiley & Sons, 2009, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Mirkovic, Alexander. "Angels and Demons: Yugoslav Resistance in the American Press 1941–1945". World History Connected, University of Illinois website, 2012.

- ^ "How did Robert De Niro fall in love with Serbia".

- ^ "Boycie in Belgrade". YouTube. 28 July 2020.

- ^ K. Stuart Parkes (January 2009). Writers and Politics in Germany, 1945–2008. Camden House. pp. 174–. ISBN 978-1-57113-401-1.

- ^ Reljic, Dusan; Markovic, Predrag; Sebor, Janko; Mijovic, Vlastimir (16 November 1992). "Limonov & Co". scc.rutgers.edu. Vreme News Digest.

- ^ "LIMONOV Junak našeg doba". Печат - Лист слободне Србије (in Serbian). 22 September 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ "in Serbia at Belgrade told him "I am not Spanish from there [Spain], but Spanish from the East." Andreu, Miguel Rodríguez (31 January 2017). "Serbia fuera del radar estratégico de España". esglobal. https://www.esglobal.org/serbia-del-radar-estrategico-espana Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors, 1801 -1927. CUP Archive. 1966. pp. 529–. GGKEY:5L37WGKCT4N.

- ^ Даница 2009, Вукова задужбина, О породичним приликама краља Владислава, Душан Спасић, 253–263, Београд, 2009

- ^ Józef Bartłomiej Zimorowic (1857). "Śpiewacy" (in Polish). Kazimierz Józef Turowski, ed. Sielanki Józefa Bartłomieja i Syzmona Zimorowiczów. The Internet Archive. p.39

- ^ Theodoulou, Christos A. (1971). Greece and the Entente, August 1, 1914-September 25, 1916. p. 151.

Sir Henry Bax - Ironside, who was considered Serbophil..

- ^ Lambros Koutsonikas (1863). Genikē historia tēs Hellēnikēs Epanastaseōs. p. 121. OCLC 679320348.

- ^ Bled, Jean-Paul; Terzić, Slavenko (2001). Europe and the Eastern Question (1878–1923): Political and Organizational Changes. Istorijski institut SANU. pp. 324–325. ISBN 978-86-7743-023-8.

- ^ Acović, Dragomir (2012). Slava i čast: Odlikovanja među Srbima, Srbi među odlikovanjima. Belgrade: Službeni Glasnik. p. 632.

- ^ Serbia, RTS, Radio televizija Srbije, Radio Television of. "Ју Хуа за РТС: Волим Србију, долазим чим прође пандемија". www.rts.rs. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kořan, Michal (2010). Czech Foreign Policy in 2007-2009: Analysis. Ústav mezinárodních vztahů. p. 243. ISBN 978-8-08650-690-6.

Sources

- Sells, David (1997). Serb 'Demons' Strike Back (Royal Institute of International Affairs) Vol. 53, No. 2

- Tomić, Dejan (2019). Srbi i evropski kompozitori: srpska muzika i Srbi u delima evropskih kompozitora, od XIX do početka XXI veka [Serbs and European composers: Serbian music and Serbs in the works of European composers, from the 19th to the beginning of the 21st century]. JMU Radio-televizija Srbije. ISBN 978-8-66195-173-2.

External links

The dictionary definition of serbophilia at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of serbophilia at Wiktionary