Wilford Woodruff

| Wilford Woodruff | |

|---|---|

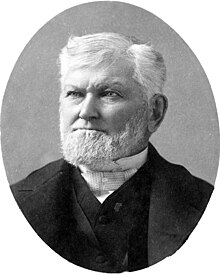

Woodruff in 1889 | |

| 4th President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints | |

| April 7, 1889 – September 2, 1898 | |

| Predecessor | John Taylor |

| Successor | Lorenzo Snow |

| President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles | |

| October 10, 1880 – April 7, 1889 | |

| Predecessor | John Taylor |

| Successor | Lorenzo Snow |

| End reason | Became President of the Church |

| Quorum of the Twelve Apostles | |

| April 26, 1839 – April 7, 1889 | |

| Called by | Joseph Smith |

| End reason | Became President of the Church |

| Apostle | |

| April 26, 1839 – September 2, 1898 | |

| Called by | Joseph Smith |

| Reason | Replenishing Quorum of the Twelve[nb 1] |

| Reorganization at end of term | Rudger Clawson ordained |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 1, 1807 Farmington, Connecticut, United States |

| Died | September 2, 1898 (aged 91) San Francisco, California, United States |

| Resting place | Salt Lake City Cemetery 40°46′33″N 111°51′45″W / 40.77592°N 111.86247°W |

| Spouse(s) | Phebe Whittemore Carter

(m. 1837; died 1885)Mary Ann Jackson

(m. 1846; div. 1848)

(m. 1878; died 1894)Sarah Elinor Brown

(m. 1846; div. 1846)Mary Caroline Barton

(m. 1846; div. 1846)Mary Meeks Giles Webster

(m. 1852; died 1852)Clarissa Henrietta Hardy

(m. 1852; div. 1853)Emma Smith (m. 1853)Sarah Brown (m. 1853)Sarah Delight Stocking

(m. 1857)Eudora Young Dunford

(m. 1877; div. 1879) |

| Children | 34 (including Abraham O. Woodruff and Clara W. Beebe) |

| Parents | Aphek and Beulah Woodruff |

| Signature | |

Wilford Woodruff Sr. (March 1, 1807 – September 2, 1898) was an American religious leader who served as the fourth president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) from 1889 until his death. He ended the public practice of plural marriage among members of the LDS Church in 1890.

Woodruff joined the Latter Day Saint church after studying Restorationism as a young adult. He met Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint movement in Kirtland, Ohio, before joining Zion's Camp in April 1834. He stayed in Missouri as a missionary, preaching in Arkansas and Tennessee before returning to Kirtland. He married his first wife, Phebe, that year and served a mission in New England. Smith called Woodruff to be a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in July 1838, and he was ordained in April 1839. Woodruff served a mission in England from August 1839 until April 1841, leading converts from England to Nauvoo. Woodruff was away promoting Smith's presidential campaign at the time of Smith's death. After returning to Nauvoo, he and Phebe traveled to England, where Woodruff preached and supported local members. The Woodruffs returned to the United States just before the Saints were driven out of Nauvoo, and Woodruff oversaw forty families in Winter Quarters, where he was sealed to his first plural wives. He joined the advance company that traveled to the Salt Lake Valley without his family in 1847. After returning to Winter Quarters, Woodruff and Phebe left to preside over the Eastern States Mission.

Woodruff and his family arrived in Salt Lake City on October 15, 1850. He served in the Utah territorial legislature and was heavily involved in the social and economic life of his community. He worked as an Assistant Church Historian and as Church Historian from 1856 to 1889. He was married to three more wives between 1852 and 1853. In 1877, he became president of the St. George Temple, where endowment ordinances were first performed for the dead as well as the living. Woodruff helped standardize the temple ceremony and decreed that church members could act as proxy for anyone they could identify by name. He also ended sealings of members to unrelated priesthood holders. In 1882, Woodruff went into hiding to avoid arrest for unlawful cohabitation under the Edmunds Act. In 1889, Woodruff became the fourth president of the LDS Church. After government disenfranchisement of polygamists and women in Utah Territory and seizure of church properties, which threatened to extend to temples, Woodruff ended the church's official support of new polygamous marriages in the 1890 Manifesto. Woodruff died in 1898 and his detailed journals provide an important record of Latter Day Saint history.

Early years and conversion

[edit]Woodruff was one of four sons born to Beulah Thompson and Aphek Woodruff. Beulah died of "spotted fever" in 1808 at the age of 26, when Wilford was fifteen months old. Aphek married Azubah Hart in 1809.[1] In 1826, Aphek lost his mill and moved from Northington (Avon, Connecticut) to Farmington, Connecticut.[2] Woodruff attended school until he was 18 years old, which was unusual at the time. He survived having typhus and numerous accidents. At age 20, Woodruff left home to manage a flour mill for his aunt, and after three years, operated mills for other people until moving to Richland, New York, with his brother, Azmon, in 1832. During his time as a mill operator, he studied religion and became interested in Restorationism.[3] Woodruff had his local Baptist minister, Mr. Phippen, baptize him without making him a member of the local congregation.[4] Woodruff joined Smith's original Church of Christ on December 31, 1833. He was impressed with how the missionaries (Zerah Pulsipher and Elijah Cheney) preached their message voluntarily and free of charge, and how they purported to heal the sick.[5]

Zion's Camp and mission

[edit]Woodruff left his home in Richland after members recruited him to join Zion's Camp in April 1834. He met prominent church leaders, including Joseph Smith, in Kirtland, Ohio, before leaving with Zion's Camp for Missouri in May.[6] When Zion's Camp left Missouri, Woodruff stayed to help members in Clay County, Missouri.[7] He was ordained as a priest in 1834 and volunteered to serve a mission. After donating all his belongings to the church, Woodruff left Kirtland on January 12, 1835, preaching without "purse or scrip" in Arkansas and Tennessee. Woodruff's original companion was Harry Brown, who later left Woodruff to return to his family in Kirtland. Most of the mission, Woodruff preached in small towns and villages in western Kentucky and Tennessee and supported new members there. Warren Parrish ordained Woodruff as an elder in June 1835, and Woodruff heard in February 1836 that Smith had called him as a member of the Second Quorum of the Seventy.[8]

Woodruff was dedicated to the Latter Day Saint Church, which distanced him from his family, who did not believe in the church. He returned to Kirtland in November 1836, where he studied Latin and Greek grammar at the Kirtland School, a school for adult education, which met in the attic of the Kirtland Temple.[9] In January 1837, Smith called Woodruff to join the First Quorum of the Seventy.[10] Three months later, over a period of five days, he participated in washing and anointings in the Kirtland Temple, accompanied by prolonged fasting and prayer and Charismatic experiences, such as speaking in tongues and prophecy.[11]

Marriage and family

[edit]Like many early Latter-day Saints, Woodruff practiced plural marriage. Woodruff was married to ten women in total, although not at the same time.[12] His first wife, Phebe, stated that she thought plural marriage was "the most wicked thing I ever heard of", but she eventually embraced it.[13]

His wives:

- Phebe Whittemore Carter (March 8, 1807 – November 10, 1885), m. April 13, 1837

- Mary Ann Jackson (February 18, 1818 – October 25, 1894) m. April 15, 1846, or August 2, 1846 (divorced in 1848 but resealed in 1878)[13][14]

- Sarah Elinor Brown (August 22, 1827 – December 25, 1915) m. August 2, 1846 (divorced after 3 weeks)[15]

- Mary Caroline Barton (January 12, 1829 – August 10, 1910) m. August 2, 1846 (divorced after 3 weeks)[15][nb 2]

- Mary Meek Giles Webster (September 6, 1802 – October 3, 1852) m. March 28, 1852 (died 7 months after sealing)[17]

- Clarissa Henrietta Hardy (November 20, 1834 - September 3, 1903) m. April 20, 1852 (divorced in 1853)[17]

- Emma Smith (March 1, 1838 – March 4, 1912) m. March 13, 1853[17]

- Sarah Brown (January 1, 1834 – May 9, 1909), m. March 13, 1853[17]

- Sarah Delight Stocking (July 26, 1838 – May 28, 1906) m. July 31, 1857[17]

- Eudora Young Dunford (May 12, 1852 – October 21, 1921) m. March 10, 1877 (divorced in 1879)[17]

Six of Woodruff's wives bore him a total of 34 children, with three wives and 14 children preceding him in death.[18]

Woodruff met his first wife, Phebe Carter, in Kirtland shortly after his return from his first mission through Southern Missouri, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Kentucky. Woodruff came to Kirtland on November 25, 1836, along with Abraham O. Smoot. He was introduced to Phebe by Milton Holmes on January 28, 1837. She was a native of Maine and had become a Latter Day Saint in 1834. Woodruff and Phebe were married on April 13, 1837, with the ceremony performed by Frederick G. Williams.[19] Their marriage was later sealed in Nauvoo by Hyrum Smith.[20] Due to a loss of records, this ordinance was later repeated by Heber C. Kimball in Salt Lake City in 1853.[21] Phebe accompanied her husband on his 1837–1838 mission to the Fox Islands in Maine. During some of this time, she resided with her parents in their house in Maine. She headed west with her husband shortly after the birth of their daughter, despite her reluctance to leave home.[22]

During their journey west, Phebe became deathly ill. She frequently slipped into unconsciousness starting on December 2, 1838. Phebe reported that she conversed with two angels who gave her the choice to live or die. They said that she could choose to live if she would accept the responsibility of supporting her husband in all of his future work for the Lord; she chose to live and persevere with the faithful.[23] She recovered after receiving a blessing from Woodruff.[24] Her firstborn child died of a respiratory infection in 1840 while Woodruff was on a mission in England.[25] Phebe was among the members of the Relief Society in Nauvoo.[26] In the late 1840s, Phebe was set apart as a missionary and served with Woodruff as he presided over the Eastern States Mission. Phebe was later numbered among the "leading ladies" who helped organize the Relief Society in Utah Territory in the 1860s through the 1880s.[27] She was also a key figure behind the Indignation Meeting of 1870 that was an important step in the women of Utah being granted the right to vote.[28]

Woodruff's second marriage to Mary Ann Jackson ended in divorce a year after their son, James, was born in 1847.[13] Woodruff's third and fourth marriages ended in divorce only three weeks after their sealing, after the two young women started dating men their own age.[15] In 1852, Woodruff married Mary Giles Meeks Webster and Clarissa Henrietta Hardy, but Mary died that same year and Clarissa divorced him a year later. In 1853, he was sealed to two more women, Emma Smith, age 15, and Sarah Brown, age 19. Sarah bore a son the following year, but Emma did not bear any children until she was 19.[21] Emma's first child died at age 13 months, and her fourth child, born in 1867, died soon after birth.[29] In 1857, Brigham Young sealed Sarah Delight Stocking to Woodruff.[21] Delight's third child died as an infant in 1869.[29] In 1877, Young sealed his daughter, Eudora Lovina Young Dunford, to Woodruff. Their child died a few hours after birth in 1878. Although Woodruff and Mary Ann Jackson were divorced, he provided a home for her and sent money to her to support her and their son, James.[21] James came to live with Woodruff as a young man in 1863.[29] Among Woodruff's children was church apostle Abraham O. Woodruff.[30] Woodruff's daughter Phebe was sealed as a wife to Lorenzo Snow in 1859.[29]

During Woodruff's time as president of the LDS Church, his wife Emma Smith Woodruff accompanied him to public functions, and she was the only wife he lived with after Phebe's death in 1885.[31] She was a niece of Abraham O. Smoot. Although she married Woodruff, then age 46, when she was 15, she did not have the first of her eight children until she was 19. Emma was involved in the Relief Society, serving as both a ward and stake president for that organization. She also served as a member of the Relief Society General Board from 1892 to 1910.[32] Woodruff spent more time with Emma's children than his children from other wives. He corresponded most frequently with Emma's and Phebe's children, giving them advice on living a virtuous life and saving money. He built homes for his wives, and he sent money to his wives and children, probably based on their individual needs.[33]

In the 1880s, Woodruff met Lydia Mary Olive Mamreoff von Finkelstien Mountford, who grew up Christian in Jerusalem. Woodruff and Mountford became friends, and she spent time with Woodruff's family at their summer home.[34] While historian D. Michael Quinn and others have speculated that Mountford was sealed to Woodruff as a plural wife in 1897,[35] there is no evidence for it. According to Thomas G. Alexander, Mountford was away giving lectures in California while Woodruff was in Oregon at the time that Quinn postulated they were sealed.[36]

Missionary work and work as an apostle

[edit]Mission in the east and England; ordination as apostle

[edit]On May 30, 1837, a month after his marriage to Phebe, Woodruff left Kirtland with Jonathan Hale and Milton Holmes to serve a mission in New England. According to their accounts, the main places they preached were The Fox Islands, Litchfield County, Connecticut, and York County, Maine. Phebe joined Woodruff in Farmington, Connecticut, on July 16, where he baptized some of his relatives. Baptizing his family brought him great joy, saying that it was in fulfillment of a dream he had when he was young.[37] Although Phebe did not accompany him on all of his journeys over the next year and a half, she stayed at various locations in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Maine—locations that he, to some extent, made his base of operations. Woodruff baptized over 100 people during this mission.[38] In 1838, Woodruff led a party of 53 members in wagons from the Maine coast to Nauvoo, Illinois. Some of the party wintered in Rochester, Illinois, after hearing about the growing persecution of members in Missouri.[39] They moved to Quincy, Illinois, in April 1839.[40]

In July 1838, Smith called Woodruff as a member of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles.[41] He was ordained at Far West, Missouri, in April 1839 where the other members of the Quorum of the Twelve had traveled.[42] He suffered from malaria in Commerce, Missouri, during the July epidemic.[43] In 1839, he and John Taylor were the first two apostles to leave from the Nauvoo/Montrose area to go on missions to Britain.[44] He spent over a month in the Staffordshire Potteries and then traveled to Herefordshire, where he preached to members of the United Brethren. Almost all of the members of the United Brethren converted to Mormonism.[45] Outside of London, the missionary work in England was successful, and by August 1840, there were around 800 members, with local members acting as leadership and proselyting missionaries. Preaching in London was difficult, and Woodruff had dreams about serpents attacking him before he and his companions were able to baptize 49 people.[46] Many converts left to join the other members in the United States. When he left England in April 1841, 140 members joined him in journeying to New York.[47] Woodruff met Phebe in Maine, and they traveled to Nauvoo together in October 1841.[48]

Nauvoo and Winter Quarters

[edit]

In Nauvoo, the Twelve Apostles assigned Woodruff to assist with the church's temporal matters in Nauvoo. He became co-manager of Times and Seasons in February 1842. Woodruff supervised the physical printing of the paper, and he and John Taylor also published a general interest newspaper called Nauvoo Neighbor, starting in May 1843. He bought and sold real estate, helped clerk in a provision store, and farmed. He became a member of the Nauvoo city council and served as chaplain for the Nauvoo Legion, a local militia. He also helped organize the Nauvoo Masonic Lodge and the Nauvoo Agricultural and Manufacturing Society.[49] As one of the church's apostles, he was also a member of the Council of Fifty.[50] He took detailed notes on the King Follett discourse. He joined the other apostles in a trip to the East Coast to raise funds for a temple and hotel under construction in Nauvoo, setting out in July 1843 and returning in November 1843.[51] Woodruff and his wife, Phebe, received their second anointing in Nauvoo in 1844,[52] making them members of the Anointed Quorum.[53] In May 1844, Woodruff left on another trip to preach and promote Joseph Smith's presidential campaign. News of Smith's death reached Woodruff on July 9, and fellow apostles returned to Nauvoo in August.[54]

The apostles called Woodruff and Phebe to serve in England. They left Nauvoo in August 1844, leaving their eldest child with a family in Nauvoo. They left their three-year-old with Phebe's parents in Maine, bringing their one-year-old with them to England.[55] Woodruff worked to square the mission account books and visited wards and branches throughout the United Kingdom, establishing the authority of the apostles after Smith's death. Members in England tried to form a joint stock company trading with Nauvoo in cotton, wool, and iron. The company failed because of unrest in Nauvoo and problems in management. After hearing that members had been driven out of Nauvoo, the Woodruffs left England in January 1846. Woodruff picked up their daughter and brought some of his relatives with him to Nauvoo, but Woodruff's relatives decided to join James Strang's followers rather than move west.[56]

Before leaving Nauvoo, Woodruff and Orson Hyde dedicated the temple on April 30, 1846.[57] Woodruff oversaw 40 families, and they stayed at Winter Quarters. Many people got sick in Winter Quarters, and Woodruff's 16-month-old son, Joseph, died of a respiratory infection on November 12, 1846. Phebe's friend from England, Jane Benbow, also died, and Phebe went into labor 6 weeks early, giving birth to a son who died two days after birth. Woodruff joined an advance company that left in April 1847 to find a place to settle, leaving his family in Winter Quarters.[58] Woodruff suffered various ailments, as did most of the other migrants. They arrived in the Salt Lake Valley on July 24 and immediately planted crops.[59] Woodruff learned to fly fish in England, and his 1847 journal account of his fishing in the East Fork River is the earliest known account of fly fishing west of the Mississippi River.[60] Woodruff returned to Winter Quarters that October 31; Phebe was there and had given birth three days earlier to a daughter named Shuah.[61] The apostles assigned Woodruff to preside over the Eastern States Mission, centered in Boston. Phebe was specially blessed to teach and be a mother in Israel, and they left Winter Quarters in June 1848. Shuah died, probably of dysentery, on July 22 during the journey east. Phebe went with the children to visit her father in Maine while Woodruff organized church work on the East Coast. He organized branches, preached, and resolved conflicts.[62] In 1849, Phebe's father and a sister joined the church. Woodruff led 200 members in traveling west, starting in February 1850. They arrived in Nebraska in May 1850, where the price of oxen and their drivers was steep. The trail was heavily grazed by other travelers, leaving little food for their oxen and half died. Woodruff sent word to Brigham Young that his party needed oxen, and a party from Salt Lake City arrived on October 8. Woodruff's group arrived in the valley on October 15.[63]

Settling Utah

[edit]

Woodruff initially focused on building cabins, farming, and grazing his cattle. He experimented with different varieties of wheat. He sold goods from outside of Utah in a retail store. His efforts were not successful, and he focused on farming and herding in 1856. In 1852, Woodruff began serving as church historian.[65] Phebe gave birth to Bulah in 1851 and to a son who died shortly after birth in 1853. Wilford adopted an orphaned Paiute boy named Moroni Bosnel in 1855. He also purchased a 6-year-old Paiute boy; it is unclear if the boy was part of the household as a slave or a son.[66] An adopted son named Saroquetes helped Wilford Jr. manage day-to-day ranching duties in the 1850s and 1860s.[67]

Woodruff served multiple terms in the Utah territorial legislature. He was a member of the legislative house from its formation in 1851 until 1854, and then served in the legislative council from 1854 until 1876.[68][69][70] Woodruff promoted public schools and noted attendance statistics when he traveled to southern Utah.[71] Woodruff served as a member of the 1862 Utah Constitutional Convention and the committee that drafted the appeal to the U.S. Congress to approve the constitution and grant statehood for Utah. This attempt to join the Union failed.[72] Woodruff served as a member of the Provo City Council in 1868 and 1869.[73]

Woodruff was also on the Board of Regents of the University of Deseret, where he chaired a committee to prepare spelling books in the Deseret Alphabet.[74] Woodruff spent some time in 1854 educating his own children at home before public schools were established. He was president of a society for a lecture and discussion group called the Universal Scientific Society, founded in February 1855 and disbanded in November 1855.[75] He also attended meetings of the Polysophical Society, a literary group including Lorenzo and Eliza Snow. The society stopped meeting after the Mormon Reformation in 1856. Woodruff was president of the Deseret Horticultural Society, founded in September 1855, which sought to find the most productive trees and bushes. By his own report, he had cultivated over 70 kinds of apples via importing and grafting, along with apricots, peaches, grapes, and currants in 1857.[76] On multiple occasions, his products won prizes at the Utah Territorial Fair.[77][78] Woodruff led the Deseret Agricultural and Manufacturing Society from 1862 to 1877. The organization encouraged experimentation and shared knowledge about what plants would grow well in the territory. The Utah Territorial Legislature chartered it in 1856.[79]

Woodruff sometimes led ceremonies in the Endowment House after it was built in 1855, officiating every Saturday in sealings and endowments in 1867 to 1868.[80] He served a "home mission" to reactivate lapsed members and call them to repentance, preaching for a renewed commitment to religion throughout the Mormon Reformation.[81] During the time of the Utah War, he moved his family south to Provo in April 1858; they moved back to Salt Lake City in July.[82] During this time there were no public worship services in Salt Lake City, and Woodruff and the other members of the Twelve Apostles organized groups of priesthood holders that met regularly to pray and preach to one another.[83] Woodruff's wife Sara lived and taught school in Fort Harriman in 1860; she returned to Salt Lake City by 1865. His wife Delight moved to Fort Harriman in 1862, and her parents also lived there. In 1866, Emma moved to a house on Woodruff's farm just outside Salt Lake City.[84] In 1868, Woodruff was elected to be part of the city council in Provo; Delight moved to Provo to facilitate his work there.[85]

Woodruff was the founding director of Zion's Cooperative Savings Bank in August 1871. He was also on the board of directors for ZCMI. When Brigham Young set up United Order communities in 1874, Woodruff helped organize United Orders in Provo, Pleasant Grove, American Fork, and Lehi, but did not enroll in the communalist program himself. Most United Order programs stopped functioning after a few months. Woodruff started keeping bees in 1870, and founded a society for beekeepers in Utah territory that year.[86] He and Phebe moved to a smaller house in 1871, since their children were no longer living at home.[87] Woodruff's other wives still continued to bear children and needed larger places to live. Woodruff's wife Sarah and his son's family moved to Randolph, Utah, in 1871, and he built a house for Sarah in 1872.[88] Woodruff bought new mowers and rakes, which he used at both Randolph farm and his Salt Lake City farm in 1873.[86] He built a house for Delight in 1876 in Salt Lake City.[88] He helped his older sons, Wilford Jr. and David Patten, with their own farming businesses. Phebe was still Woodruff's most visible wife, appearing with him in public.[87]

St. George Temple President

[edit]Beginning in 1877, Woodruff was the first president of the St. George Temple. This was the first temple in which the endowment ordinances were performed for the dead as well as for the living. Under the direction of Brigham Young, Woodruff was key in implementing endowments for the dead in the temple, in standardizing the ceremonies, and in giving various sermons to encourage broader understanding of the program.[89] Woodruff helped John D. T. McAllister with writing parts of the temple ceremony.[90] McAllister served as first counselor in the temple presidency and later succeeded Woodruff as temple president in 1884.[91] In February 1877, Woodruff received a revelation that church members could act as a proxy in the temple for not only their own relatives, but for anyone they could identify by name.[92] Woodruff stated that temple presidents were "authorized to exercise discretion in permitting persons to be baptized for friends."[93] In 1893, Lorenzo Snow made it a policy that heirs should request in writing for others to perform temple work for their relatives.[93]

Woodruff spent his 70th birthday working in the temple in 1877. 154 women from St. George performed temple ordinances vicariously for women who "had previously been sealed to [Woodruff] vicariously" and those who were related to him, Thompson, or the Hart families.[94] Two years earlier, in 1875, Woodruff performed baptisms for the dead on behalf of 141 of his relatives in the Endowment House and for over 900 more in that same year.[95] Woodruff accepted Brigham Young's daughter Eudora as a plural wife in 1877; their union produced a son who died shortly after birth. Eudora divorced Woodruff, probably in 1879.[94] Woodruff, Phebe, and their living children (except for Susan) met and performed more temple work, and at this time, Woodruff adopted various relatives to himself in the temple. He also sealed five single women to his recently deceased son Brigham.[96] He was baptized on behalf of the signers of the U.S. Declaration of Independence and other Founding Fathers. He stated in a September 16, 1877, discourse that he had been visited by the departed spirits of these men.[97] Many of the proxy baptisms for the Founding Fathers had been done previously in Nauvoo and in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City, but the proxy endowments for these men were first done in the St. George Temple. Woodruff also compiled lists of notable men and women, for whom he performed vicarious temple work with the help of Lucy Bigelow Young.[98][96]

After Brigham Young's death in August 1877, John Taylor became the new president of the church, and Woodruff became president of the Twelve Apostles. Woodruff chaired the committee to separate Brigham Young's personal property from church property, finding that Brigham Young owed the church almost $700,000 in real-estate and other expenses.[99] In 1879, George Reynolds was convicted of polygamy in a U.S. Supreme Court ruling. Utah's U.S. marshal started looking for Woodruff, and Woodruff fled to Bunkerville, Nevada, northern Arizona, and New Mexico. A new Supreme Court ruling required the federal government to provide positive evidence of polygamy before convicting the husband, and Woodruff could appear in public again until the 1882 when the Edmunds Act was passed.[100] The Edmunds Act outlawed unlawful cohabitation, which was easier to prove than polygamy, and church leadership advised men in polygamous marriages to live in one house with one wife. Prosecution of polygamous men began in earnest in 1884, and Woodruff went into hiding in St. George during 1885 and often wore a dress and sunbonnet as a disguise.[101][102][103] He was able to visit Phebe before her death on November 9, 1885, but fearing arrest, did not attend her funeral, instead watching it from the president's office. After Phebe's death, he lived at Emma's house or with friends.[104]

President of the Church

[edit]

Polygamy and legal disputes

[edit]After the death of John Taylor in July 1887, Woodruff assumed leadership of the church as the senior member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Woodruff wanted to reorganize the First Presidency right away, continuing with George Q. Cannon as first counselor. Other members of the Quorum took this opportunity to raise grievances against Cannon, stating that he had defended his son John Q. too vigorously during his excommunication, to the point of hiding his crimes. The Twelve Apostles with Woodruff as its president presided over the church until the Quorum came to an agreement in April 1889. After George Q. Cannon apologized to the Quorum, they approved his appointment as first counselor.[105] In 1887, the new U.S. marshal, Frank H. Dyer, told Woodruff he would not arrest him, and Woodruff could make public appearances again in Salt Lake City. Outside of Salt Lake City, deputy marshals vigorously hunted down suspected polygamists, being paid more with more convicts.[106] In an effort to appear more attractive for statehood, Woodruff counseled local press not to excessively criticize the federal government and asked missionaries in the southeastern United States to soften their approach to decrease complaints from local ministers. He also asked leaders to stop preaching the practice of plural marriage.[107] On behalf of the church, Woodruff courted the favor of businessman Alexander Badlam Jr. and prominent Republican Isaac Trumbo. The two men moved to Arlington, Virginia, under false names, seeking to persuade Republican congressmen to support Utah's bid for statehood in 1888. After Utah was denied statehood, Woodruff personally traveled to California in 1889 to speak with politicians.[108]

During Woodruff's tenure, the church faced a number of legal battles with the United States. The Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act of 1862 made it illegal for religious entities to own property worth more than $50,000 in any territory, and the Edmunds–Tucker Act of 1887 put forth the procedure for confiscating Church property. Marshal Dyer became the federally-appointed receiver of church property, and he confiscated the temple block, the Gardo House, and other offices. The church paid to rent the properties back from him. Church leadership discouraged new polygamous marriages in Utah. Late in 1889, federal judges stopped approving naturalized citizenship for Mormon immigrant residents in Utah Territory. Judges cited a disdain for federal law, pointing to doctrines such as blood atonement and temple vows as reported from former members to avenge the government for Joseph Smith's death. Other former members testified that an oath against the federal government was not part of the endowment ceremony. Another $3 million in church assets were confiscated in 1887. Judge Anderson ruled against the naturalization of Mormon residents.[109] In response, Charles Penrose wrote a manifesto, signed by the First Presidency and the Twelve, in December 1889. This manifesto denied that the church had any right to overrule any civil court, denied the doctrine of blood atonement, asserted their right to criticize government officials, and the right of all Christians to believe that "the kingdom of heaven is at hand". Historian Thomas Alexander stated that both the judge's interpretation of church history and the manifesto were "a selective reading" of church history.[110]

The Edmunds-Tucker Act also took away the right to vote from practicing polygamists and all women in Utah. Combined with the influx of non-Mormons, the church could no longer control political offices in Utah Territory, and the members of the Liberal Party achieved a majority over the People's Party in 1890.[111] In June 1890, the First Presidency told church officials that leaders were no longer allowed to perform plural marriages in the United States. Henry W. Lawrence replaced Marshal Dyer and threatened to confiscate the temples in Logan, Manti, and St. George, as they were not used for public worship.[112] Woodruff issued the 1890 Manifesto, which officially ended the church's support of plural marriage.[113] After the manifesto was issued, judge Charles S. Zane stated that no further church property would be confiscated.[31] Woodruff further clarified in hearings about confiscated church property that men with plural wives should "cease associating with them", though Joseph F. Smith and Lorenzo Snow did not make such strong statements. When the First Presidency suggested issuing another manifesto to tell polygamous men from associating with plural wives, Woodruff said that a man who neglected his wives and children could face church discipline.[114] Law professor[115] Kenneth L. Cannon II states that Woodruff's intent with the 1890 Manifesto was to stop the creation of more plural marriages but allow existing ones to continue.[116] The judge in the hearing decided not to return confiscated property to the church, stating that while the practice of polygamy may have stopped, it was still taught as part of the religion. Lobbyists managed to obtain amnesty for Mormons who did not enter polygamy after November 1890, but polygamists still did not have the right to vote. When Democrats took office in 1893, they restored property to the church and civil rights to members of the church.[114] Historian Thomas Alexander stated in his biography of Woodruff that Woodruff's decision to stop polygamy was a significant transition "from isolation to assimilation, from extremism to respectability".[117]

Some Mormon historians, such as B. H. Roberts, never seemed to come to terms with the manifesto.[118] Despite the manifesto, some Mormon historians have asserted that Woodruff continued to secretly allow new plural marriages to be performed in Mexico, Canada, and upon the high seas.[119][120][121]

Temple changes and church economic stimulus efforts

[edit]Starting in 1847, members of the church sealed their relatives to a family member or friend who held the priesthood, since Brigham Young said that all marriages before the Restoration were illegitimate.[122] Brigham Young also stated that children born outside of marriage should be sealed to the parent who lived the Gospel and adopted through a special sealing to a faithful priesthood holder. Woodruff and other members disagreed with the law of adoption. Woodruff and Heber C. Kimball discussed the law of adoption together in 1857, agreeing that they did not believe in the "custom of adoption", and that sons ought to be sealed to the fathers in their lineage when possible.[123] In a conference address from April 1894, Woodruff announced a specific policy of sealing individuals only to their direct ancestors. He also encouraged members to "trace their genealogies as far as they can".[124] Woodruff helped found the Genealogical Society of Utah to help church members complete generational sealings.[125][126] In Wilford's 1894 address, he also stated that widows could be sealed to their deceased husbands, even if their husbands had never heard the gospel. Woodruff stated that this change in practice was not a change in doctrine, since Joseph Smith had referred to a welding link between fathers and their children.[127] Woodruff also encouraged presidents of the four temples in the Utah Territory to coordinate their temple procedures in 1893.[128]

An economic recession in 1891 followed by another depression in 1893 affected the church's finances. Bishops used fast offerings as well as tithing to help the poor, and as a result, less money ended up in church headquarters. From July until December 1893, the church was unable to pay the salaries of its employees. Woodruff tried to promote economic development with various ventures, including the Utah Sugar Company at Lehi. The company was not successful and created over $300,000 in debt for the Church.[129] The church also supported local industries like coal and iron mining, the Saltair resort, and the state's first hydroelectric generating facility.[117] The church completed and dedicated the Manti and Salt Lake temples during his tenure. Woodruff also established Bannock Academy in Rexburg, Idaho, which later became Ricks College and Brigham Young University–Idaho.

Political manifesto

[edit]Moses Thatcher and B. H. Roberts attended the 1895 state constitutional convention as Democrats. Both were general authorities of the church. Roberts opposed women's suffrage, while Woodruff and the First Presidency supported it. Thatcher had issues with chronic ulcers and a morphine addiction, and in the rare times when he was in good health, he often failed to attend meetings. Thatcher ran as the Democratic Party's nominee for senate. Heber J. Grant said that Thatcher should have consulted with the other apostles and the First Presidency before accepting the nomination for senate. Thatcher argued that the First Presidency did not have the right to limit a member's political decisions. At a general priesthood session, Joseph F. Smith said that any obligations that take a member away from their religious duties should be discussed with their presiding officers. He said that any Melchizedek priesthood holder ought to have permission from his church leaders before pursuing a political office.[130] Republican leaders connected Smith's statements with Thatcher and Roberts's political activity and used it to criticize the Democratic Party. Smith's remarks became controversial, with some members calling for the church to not interfere in politics, and with others supporting Smith's position. In response, Woodruff published a statement where he stated that the church did not wish to interfere with members' political endeavors. In December 1895, Woodruff said that Thatcher and Roberts would not be presented for the traditional vote of approval at April's general conference until both repented. Utah became a state with a Republican majority in the state government. Thatcher refused to reconcile with the apostles and continued to experience ill health.[131] George Q. Cannon drafted a "Political Manifesto" at Woodruff's request. It stated that religion and politics had always been separate in the church, but that people in full-time church positions should get approval from the First Presidency before accepting a political nomination.[132][133] All members of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve signed the document, except for Thatcher. The First Presidency agreed to drop Thatcher's name from the sustaining vote portion of general conference. Thatcher publicized his side of the dispute in a note in The Salt Lake Tribune. Church leaders asked for sustaining votes for the manifesto in local meetings, leading to some disputes.[132] Joseph F. Smith, a Republican, wanted the manifesto to apply to all members, but Woodruff and Cannon disagreed with Smith.[134] After several failed attempts at reconciliation, the Twelve disfellowshipped Thatcher, removing him from his position as an apostle.[135]

Death and legacy

[edit]

Woodruff died in San Francisco, California, on September 2, 1898, after a failed bladder surgery.[136] He was succeeded as church president by his son-in-law, Lorenzo Snow. Woodruff was buried at the Salt Lake City Cemetery.[137]

Woodruff's journals are a significant contribution to LDS Church history. He kept a daily record of his life and activities within the LDS Church, beginning with his mission to the southern states in 1835.[138] Matthias F. Cowley, editor of his published journals, observed that Woodruff was "perhaps, the best chronicler of events in all the history of the Church".[139] The diaries are "one of the significant records of 19th-century Mormonism".[77] In an introduction to selections from Woodruffs journals, compiler Susan Staker wrote that the journals were "public, official—and ultimately very male".[140] In addition to writing in his diary, Woodruff wrote over 12,000 letters during his lifetime, sometimes keeping a copy for his files.[141] In his Comprehensive History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, B. H. Roberts wrote that Woodruff's record was a "priceless" documentary of the discourses of Joseph Smith and Brigham Young.[142] Woodruff's diaries are featured prominently in Laurel Thatcher Ulrich's book, A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women's Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835-1870.[143]

Woodruff was an Assistant Church Historian from 1856[144] to 1883 and was the church's eleventh official Church Historian from 1883[145] to 1889.[146] Woodruff and his assistants compiled and edited historical documents from Joseph Smith's and Brigham Young's lives. They also wrote biographies of members of the Council of the Twelve.[144] Edward Tullidge helped Woodruff write his autobiography in 1856.[147]

Woodruff's teachings as an apostle were the 2006 course of study in the LDS Church's Sunday Relief Society and Melchizedek priesthood classes.

Millennialist beliefs and apocalyptic prophecies

[edit]Throughout his life, Woodruff believed that the Second Coming of Jesus and a cataclysmic end of the world was imminent.[148] On August 23, 1868,[149] Woodruff preached a sermon in which he famously prophesied that New York City would be "destroyed by an earthquake"; Boston would be "swept into the sea, by the sea heaving itself beyond its bounds"; and Albany, New York, would be "destroyed by fire".[150][151] Speaking afterwards, church president Brigham Young stated that "what Brother Woodruff has said is revelation and will be fulfilled".[150][152] Woodruff believed that the United States would disassemble by 1890.[153] In January 1880, he received a revelation referred to as the "Wilderness Prophecy", which stated that enemies of the church would be destroyed before Christ's Second Coming and reaffirmed the importance of temples.[153]

Works

[edit]- Woodruff, Wilford (1946). G. Homer Durham (ed.). The Discourses of Wilford Woodruff. Bookcraft, Inc.

- ——— (1881). Leaves from My Journal. Juvenile Instructor Office.

- ——— (1964) [1909]. Matthias F. Cowley (ed.). Wilford Woodruff, Fourth President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: History of His Life and Labors as Recorded in His Daily Journals. Deseret News.

- ——— (2004). Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Wilford Woodruff. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. LDS Church publication number 36315.

- ———; Asahel H. Woodruff. Book of Revelations: W Woodruff (handwritten precis of Joseph Smith, Jr.'s, revelations). Church History Library: Unpublished.

- ——— (2017). "Discourses (of Joseph Smith) as reported by Wilford Woodruff". In Brenden W. Rensink; Alexander L. Baugh; Elizabeth A. Kuehn; David W. Grua; Mark R. Ashurst-McGee (eds.). Documents (Volume 6). The Joseph Smith Papers. Church Historian's Press.

See also

[edit]- Smoot–Rowlett Family

- Clara W. Beebe, one of Woodruff's daughters

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Quorum of the Twelve Apostles had not had twelve members since September 3, 1837, when Luke S. Johnson, John F. Boynton, and Lyman E. Johnson were disfellowshipped and removed from the Quorum. Since that time, William E. McLellin and Thomas B. Marsh had been excommunicated and removed from the Quorum; David W. Patten had been killed; and John Taylor and John E. Page had been added to the Quorum. The ordinations of Woodruff and George A. Smith brought membership in the Quorum of the Twelve to ten members.

- ^ There is no explicit record of Woodruff's sealings to Brown and Barton, but circumstantial evidence suggests it.[16]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 12.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 14–16.

- ^ Jessee 1986, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 21.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 32.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 34–37.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 41–42, 47.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 48.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 50–51.

- ^ Mackley 2014, pp. 79–82, 376.

- ^ a b c Alexander 1991, p. 129.

- ^ Mackley 2014, pp. 203, 351 n. 695.

- ^ a b c Alexander 1991, p. 135.

- ^ Mackley 2014, p. 321 note 284.

- ^ a b c d e f Mackley 2014, p. 376.

- ^ Mackley 2014, pp. 374–375.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Holzapfel & Holzapfel 1992, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d Alexander 1991, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Grow et al. 2018, pp. 328–333.

- ^ "Journal (January 1, 1838 – December 31, 1839)," September 11, 1838". The Wilford Woodruff Papers. December 2, 1838. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 77.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 99.

- ^ Grow et al. 2018, p. 463.

- ^ Relief Society 1966, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Douglas, Dianna (January 13, 2020). "The night 150 years ago that Utah women changed history". Deseret News.

- ^ a b c d Alexander 1991, p. 213.

- ^ Hardy, Jeffrey S. "Abraham Owen Woodruff". Mormon Missionary Diaries. Harold B. Lee Library. Retrieved June 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Alexander 1991, p. 267.

- ^ Relief Society 1966, p. 52.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 299–301.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 324–326.

- ^ Quinn 1985, p. 63.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 326–328.

- ^ "Wilford Woodruff Papers Foundation". Wilford Woodruff Papers. June 11, 1808. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 55–61.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 75; 78.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 83.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 75.

- ^ Grow et al. 2018, p. 394.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 85.

- ^ Grow et al. 2018, p. 404.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 90–93.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 95; 97.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 102.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 103–104.

- ^ Godfrey 1992, p. 327.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 108–109, 111.

- ^ Mackley 2014, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Anderson 2003, p. 154.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 111–114.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 118–119.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 121–124.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 130.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 134–137.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 139–141.

- ^ Wixom, Hartt (2006). Fishing: The Extra Edge. Cedar Fort. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-55517-867-3.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 145.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 149–151.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 156–159.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 212.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 166.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 211.

- ^ "Territory of Utah Legislative Assembly Rosters: First through Tenth Sessions". Utah State Archives and Records Service.

- ^ "Territory of Utah Legislative Assembly Rosters: Eleventh through Twentieth Session". Utah State Archives and Records Service. Utah Division of State Archives. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ "Territory of Utah Legislative Assembly Rosters: Twenty-First through Thirty-First Sessions", Research Guides, Utah State Archives Research, archives.state.ut.us/research, Utah State Archives, Division of Archives & Records Service, Utah Department of Administrative Services, State of Utah

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 169.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 206.

- ^ Smith, Joseph Fielding (1938). Life of Joseph F. Smith. Salt Lake City: Desert News Press. p. 230. OCLC 5978651.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 210.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 172–174.

- ^ a b Jessee 1994.

- ^ Jessee 1986, p. 133.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 177; 201.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 210–211.

- ^ a b Alexander 1991, pp. 220–222.

- ^ a b Alexander 1991, pp. 223–224.

- ^ a b Alexander 1991, p. 225.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 229–230.

- ^ Mackley 2014, p. 157.

- ^ Bennett 2010.

- ^ Mackley 2014, pp. 179–181.

- ^ a b Mackley 2014, pp. 220–221.

- ^ a b Alexander 1991, p. 230; 404.

- ^ Mackley 2014, pp. 152–152.

- ^ a b Alexander 1991, p. 231.

- ^ Woodruff, W. (1878) [September 16, 1877]. "Gathering of the Spirits of the Dead". Journal of Discourses. Vol. 19. Recorded by G. F. Gibbs. Liverpool, UK: William Budge. p. 229.

- ^ Stuy 2011, pp. 85–87, 93.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 239–240.

- ^ Smith, Daymon Mickel (2007). The last shall be first and the first shall be last: Discourse and Mormon history (PhD). University of Pennsylvania. p. 77. ProQuest 304833179.

[Wilford] Woodruff often hid in southern Utah, though his notoriety led to suspicions cast on anyone nearby. ... Seemingly benign requests for eggs or flour became, once Woodruff was around, indicators that the neighbors were potential spies. Yet [Emma] Squire does not report any action which verified this assumption; instead, Woodruff concealed himself in a 'mother hubbard' dress, and avoided anyone he did already trust.

- ^ "Early LDS prophet goes undercover in dress, sunbonnet". The Spectrum. St. George, UT. Gannett Co., Inc. July 12, 2006.

Emma Squire made him a 'Mother Hubbard' dress and sunbonnet, similar to the ones she wore. He put them on when he went back and forth from the house so people passing could not recognize him. ... Years later, Emma met one of Woodruff's granddaughters and learned that they still had the 'Mother Hubbard' dress and bonnet in the family. They had often wondered who made them for him. They knew the items had been used for many years when he was in hiding.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 243–244.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 248.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 249–252.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 253–256.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 257–258.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 261–263.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 265–266.

- ^ Lyman, Edward Leo (1994), "Manifesto (Plural Marriage)", Utah History Encyclopedia, University of Utah Press, ISBN 9780874804256, archived from the original on May 30, 2023, retrieved August 2, 2024

- ^ a b Alexander 1991, pp. 272–274.

- ^ "KENNETH L CANNON II". faculty.utah.edu. The University of Utah. Archived from the original on July 1, 2019. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ^ Cannon II, Kenneth L. (1978). "Beyond the Manifesto: Polygamous Cohabitation among LDS General Authorities after 1890". Utah Historical Quarterly. 46 (1): 24–36. doi:10.2307/45060569. JSTOR 45060569. S2CID 254447400.

- ^ a b Alexander 1991, p. 287.

- ^ Ostling, Richard N.; Ostling, Joan K. (1999). Mormon America: The Power and the Promise. San Francisco: HarperCollins. p. 83. ISBN 0060663715. OCLC 41380398.

- ^ Cannon II, Kenneth (January–March 1983). "After the Manifesto: Mormon Polygamy, 1890-1906" (PDF). Sunstone: 27–35.

- ^ Quinn 1985, pp. 9–105.

- ^ Hardy 1992.

- ^ Mackley 2014, p. 118.

- ^ Mackley 2014, p. 280.

- ^ Mackley 2014, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Irving 1974, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Mackley 2014, p. 290.

- ^ Mackley 2014, pp. 282–284.

- ^ Mackley 2014, p. 175.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 283–285.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 310–312.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 313–314.

- ^ a b Alexander 1991, pp. 315.

- ^ Alexander 2000, p. 701.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 317.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 319.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Alexander 1991, pp. 330–331.

- ^ Jessee 1986, p. 141.

- ^ Cowley 1909.

- ^ Staker 1993, p. xi.

- ^ Jessee 1986, p. 140.

- ^ Roberts, Brigham H. (1930), A Comprehensive History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6:354-355, Deseret Book Company, Salt Lake City, Utah.

- ^ Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher (2017). A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women's Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835-1870 (1st ed.). New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-59490-7. OCLC 955274387.

- ^ a b Alexander 1991, p. 179.

- ^ "Fifty-third Semi-Annual Conference: Third Day". Deseret News. October 10, 1883. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ "General Conference: General Authorities". Deseret Weekly. April 13, 1889.

- ^ Alexander 1991, p. 201.

- ^ Staker 1993, p. xiii.

- ^ Kenney, Scott G. (1984). Wilford Woodruff's Journal: 1833-1898 Typescript, Volume 6. Midvale, UT: Signature Books. pp. August 22, 1868.

- ^ a b Church Educational System (2002). "Section 84: The Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood". Doctrine and Covenants Student Manual. Salt Lake City, Utah: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Archived from the original on July 2, 2013.

- ^ Staker 1993, p. xiv.

- ^ Staker 1993, pp. xiv–xv.

- ^ a b Mackley 2014, p. 212.

References

[edit]- Alexander, Thomas G. (1991). Things in Heaven and Earth: The Life and Times of Wilford Woodruff, a Mormon Prophet. Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books. ISBN 1-56085-045-0. OCLC 23968564.

- Alexander, Thomas (2000). "Manifesto, Political". In Garr, Arnold K.; Cannon, Donald Q.; Cowan, Richard O. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History. Deseret Book. p. 701.

- Bennett, Richard E. (2010). "Wilford Woodruff and the Rise of Temple Consciousness among the Latter-day Saints, 1877-84". In Baugh, Alexander L.; Black, Susan Easton (eds.). Banner of the Gospel: Wilford Woodruff. Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University. ISBN 9780842527767. OCLC 658200536.

- Anderson, Devery S. (Fall 2003). "The Anointed Quorum in Nauvoo, 1842-45". Journal of Mormon History. 29 (2): 154.

- Cowley, Mattias F. (1909). Wilford Woodruff, His Life and Labors. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book.

- Godfrey, Kenneth W. (1992), "Council of Fifty", in Ludlow, Daniel H (ed.), Encyclopedia of Mormonism, New York: Macmillan Publishing, pp. 326–327, ISBN 0-02-879602-0, OCLC 24502140

- Grow, Matthew J.; Turley, Richard E.; Harper, Steven C.; Hales, Scott A., eds. (2018). The Standard of Truth: 1815–1846. Saints:The Story of the Church of Jesus Christ in the Latter Days. Vol. 1. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

- Hardy, B. Carmon (1992). Solemn Covenant: The Mormon Polygamous Passage. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01833-8. OCLC 23219530.

- Ludlow, Daniel H., Editor. Church History, Selections from the Encyclopedia of Mormonism. Deseret Book Company, Salt Lake City, UT, 1992. ISBN 0-87579-924-8.

- Holzapfel, Richard N.; Holzapfel, Jeni Broberg (1992). Women of Nauvoo. Salt Lake City: Bookcraft. ISBN 0884948358. OCLC 26799181.

- Irving, Gordon (1974), "The Law of Adoption: One Phase of the Development of the Mormon Concept of Salvation", BYU Studies, 14 (3): 291–314

- Jessee, Dean C. (1986). "Wilford Woodruff". In Arrington, Leonard J. (ed.). The Presidents of the Church. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book.

- Jessee, Dean (1994). "Woodruff, Wilford". In Powell, Allan Kent (ed.). Utah History Encyclopedia. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0874804256. OCLC 30473917. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- Mackley, Jennifer Ann (2014). Wilford Woodruff's Witness: The Development of Temple Doctrine. Seattle, Washington: High Desert Publishing. ISBN 978-0-615-83532-7. OCLC 880976216.

- Quinn, D. Michael (Spring 1985). "LDS Church Authority and New Plural Marriages, 1890-1904" (PDF). Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 18 (1): 9–105. doi:10.2307/45225323. JSTOR 45225323. S2CID 259871046. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- Staker, Susan, ed. (1993). Waiting for World's End: The Diaries of Wilford Woodruff. Salt Lake City: Signature Books. ISBN 0941214923. OCLC 25871586.

- Stuy, Brian H. (2011). "Wilford Woodruff's Vision of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence". In Taysom, Stephen C. (ed.). Dimensions of Faith: A Mormon Studies Reader. Salt Lake City: Signature Books. pp. 83–111. ISBN 9781560852124. OCLC 710044985.

- History of the Relief Society, 1842-1966. Salt Lake City: Relief Society General Board. 1966. pp. 30–31. OCLC 1549916.

Further reading

[edit]- Baugh, Alexander L.; Black, Susan, eds. (2010). Banner of the Gospel: Wilford Woodruff. Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University. ISBN 978-0-8425-2776-7. OCLC 658200536.

- Woodruff, Wilford (1881). Leaves From My Journal. Faith-Promoting Series 3. Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor Office. OCLC 7381921.

External links

[edit]Archival records

[edit]- Wilford Woodruff Papers Foundation

- Wilford Woodruff Journals and Papers, MSS 1352, Church History Catalog

- Wilford Woodruff papers, Vault MSS 798 at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library Brigham Young University

- Wilford Woodruff family letters, MSS 8173 at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library Brigham Young University. This record is digitized; click on individual items under "Box/folder" to view them.

- George A. Smith Papers at University of Utah Digital Library, Marriott Library Special Collections

Other links

[edit]- Wilford Woodruff Papers Foundation

- Wilford Woodruff Archived January 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine biography at the Joseph Smith Papers Project website

- Works by Wilford Woodruff at Project Gutenberg

- 1807 births

- 1898 deaths

- 19th-century American politicians

- 19th-century American writers

- 19th-century apocalypticists

- 19th-century Mormon missionaries

- American general authorities (LDS Church)

- American Mormon missionaries in England

- American Mormon missionaries in the United States

- American orchardists

- Apostles (LDS Church)

- Apostles of the Church of Christ (Latter Day Saints)

- Burials at Salt Lake City Cemetery

- Converts to Mormonism

- Doctrine and Covenants people

- Farmers from New York (state)

- Farmers from Utah

- General Presidents of the Young Men (organization)

- Latter Day Saints from Connecticut

- Latter Day Saints from Illinois

- Latter Day Saints from Ohio

- Latter Day Saints from Utah

- Members of the Utah Territorial Legislature

- Mission presidents (LDS Church)

- Mormon pioneers

- Official historians of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Presidents of the Church (LDS Church)

- Presidents of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles (LDS Church)

- Religious leaders from Salt Lake City

- Religious leaders from Hartford, Connecticut

- Smoot–Rowlett family

- Temple presidents and matrons (LDS Church)

- Utah city council members

- Utah Democrats

- Writers from Salt Lake City

- 19th-century American diarists

- Child marriage in the United States