Petition of Right

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | The Petition Exhibited to His Majestie by the Lordes Spirituall and Temporall and Commons in this present Parliament assembled concerning divers Rightes and Liberties of the Subjectes: with the Kinges Majesties Royall Aunswere thereunto in full Parliament.[b] |

|---|---|

| Citation | 3 Cha. 1. c. 1 |

| Introduced by | Edward Coke |

| Territorial extent | England and Wales |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 7 June 1628 |

| Commencement | 7 June 1628 |

| Other legislation | |

| Amended by | |

| Relates to | A Statute Concerning Tallage (1297), Magna Carta (1297) |

Status: Amended | |

| Revised text of statute as amended | |

| Petition of Right | |

|---|---|

The Petition of Right | |

| Created | 8 May 1628 |

| Ratified | 7 June 1628 |

| Location | Parliamentary Archives, London |

| Author(s) | Edward Coke |

| Purpose | The protection of civil liberties |

| Full text | |

The Petition of Right, passed on 7 June 1628, is an English constitutional document setting out specific individual protections against the state, reportedly of equal value to Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights 1689.[1] It was part of a wider conflict between Parliament and the Stuart monarchy that led to the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, ultimately resolved in the 1688–89 Glorious Revolution.

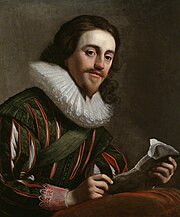

Following a series of disputes with Parliament over granting taxes, in 1627 Charles I imposed "forced loans", and imprisoned those who refused to pay, without trial. This was followed in 1628 by the use of martial law, forcing private citizens to feed, clothe and accommodate soldiers and sailors, which implied the king could deprive any individual of property, or freedom, without justification. It united opposition at all levels of society, particularly those elements the monarchy depended on for financial support, collecting taxes, administering justice etc, since wealth simply increased vulnerability.

A Commons committee prepared four "Resolutions", declaring each of these illegal, while re-affirming Magna Carta and habeas corpus. Charles previously depended on the House of Lords for support against the Commons, but their willingness to work together forced him to accept the Petition. It marked a new stage in the constitutional crisis, since it became clear many in both Houses did not trust him, or his ministers, to interpret the law.

The Petition remains in force in the United Kingdom, and parts of the Commonwealth. It reportedly influenced elements of the Massachusetts Body of Liberties, and the Third, Fifth, Sixth and Seventh amendments to the Constitution of the United States.

Background

On 27 March 1625, James I died, and was succeeded by his son, Charles I. His most pressing foreign policy issue was the Thirty Years' War, particularly regaining the hereditary lands and titles of the Protestant Frederick V, Elector Palatine, who was married to his sister Elizabeth.[2]

The pro-Spanish policy pursued by James prior to 1623 had been unpopular, inefficient and expensive, and there was widespread support for declaring war. However, money granted by Parliament for this purpose was spent on the royal household, while they also objected to the use of indirect taxes and customs duties. Charles' first Parliament wanted to review the entire system, and as a temporary measure while doing so, the Commons granted Tonnage and Poundage for twelve months, rather than the entire reign, as was customary.[3]

Charles instructed the House of Lords to reject the bill, and adjourned Parliament on 11 July, but needing money for the war, recalled it on 1 August.[4] However, the Commons began investigating Charles' favourite and military commander, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, notorious for inefficiency and extravagance. When they demanded his impeachment in return for approving taxes, Charles dissolved his first parliament on 12 August 1625.[5] The disastrous Cádiz expedition forced him to recall Parliament in 1626, but once again they demanded the impeachment of Buckingham before providing funds to finance the war, Charles adopted "forced loans"; those who refused to pay would be imprisoned without trial, and if they continued to resist, sent before the Privy Council.[6]

Ruled illegal by Chief Justice Randolph Crewe, the judiciary complied only after he was dismissed.[7] Over 70 individuals were jailed for refusing to contribute, including Thomas Darnell, John Corbet, Walter Erle, John Heveningham and Edmund Hampden, who submitted a joint petition for habeas corpus. Approved on 3 November 1627, the court ordered the five be brought before them for examination. Since it was unclear what they were charged with, the Attorney General Robert Heath attempted to get a ruling; this became known as 'Darnell's Case', although Darnell himself withdrew.[8]

The judges avoided the issue by denying bail, on the grounds that as there were no charges, "the [prisoners] could not be freed, as the offence was probably too dangerous for public discussion".[9] A clear defeat, Charles decided not to pursue charges; since his opponents included the previous Chief Justice, and other senior legal officers, the ruling meant the loans would almost certainly be deemed illegal.[10] So many now refused payment, the reduction in projected income forced him to recall Parliament in 1628, while the controversy returned "a preponderance of MPs opposed to the King".[11]

To fund his army, Charles resorted to martial law. This was a process employed for short periods by his predecessors, specifically to deal with internal rebellions, or imminent threat of invasion, clearly not the case here.[12] Intended to allow local commanders to try soldiers or insurgents outside normal courts, it was now extended to require civilians to feed, house and clothe military personnel, known as 'Coat and conduct money.' As with forced loans, this deprived individuals of personal property, subject to arbitrary detention if they protested.[13]

In a society that valued stability, predictability, and conformity, the parliament assembled in March claimed to be confirming established and customary law, implying both James and Charles had attempted to alter it. On 1 April, a Commons committee began preparing four resolutions, led by Edward Coke, a former Chief Justice, and most respected lawyer of the age.[14] One protected individuals from taxation not authorised by Parliament, like forced loans, the other three summarised rights in place since 1225, and later enshrined in the Habeas Corpus Act 1679. They stipulated individuals could not be imprisoned without trial, deprived of habeas corpus, whether by king or Privy Council, or detained until charged with a crime.[15]

Passage

Despite being unanimously accepted by the Commons on 3 April, the Resolutions had no legal power and were rejected by Charles.[16] He presented an alternative; a bill confirming Magna Carta and six other liberty-related statutes, on condition it contained "no enlargement of former bills". The Commons refused, since Charles was only confirming established rights, which he had already shown willing to ignore, while it would still allow him to decide what was legal.[17]

After conferring with his supporters, Charles announced Parliament would be prorogued on 13 May, but was now out-manoeuvred by his opponents. Since he refused a public bill, Coke suggested the Commons and Lords pass the resolutions as a Petition of Right, and then have it "exemplified under the great seal".[18] An established element of Parliamentary procedure, this had not been expressly prohibited by Charles, allowing them to evade his restrictions, but avoid direct opposition.[19]

The Committee redrafted the content as a 'Petition', which was accepted by the Commons on 8 May, and presented the same day to the Lords by Coke, with a bill approving subsidies to encourage acceptance.[20] After several days of debate, they approved it, but attempted to "sweeten" the wording; they then received a message from Charles, claiming he must retain the right to decide whether to detain someone.[18]

Despite protestations on both sides, in an age when legal training was considered part of a gentleman's education, significant elements within both Commons and Lords did not trust Charles to interpret the law. The Commons ignored both the request, and alterations proposed by the Lords to appease him; by now, there was a clear majority in both houses for the Petition as originally submitted. On 26 May, the Lords unanimously voted to join with the Commons on the Petition of Right, with the minor addition of an assurance of their loyalty, approved by the Commons on 27 May.[21]

Charles now ordered John Finch, the Speaker of the Commons, to prevent "insult", or criticism of any Minister of State. He specifically named Buckingham, and in response, John Selden moved the Commons demand his removal from office.[22] Needing money for his war effort, Charles finally accepted the Petition, but first increased the level of mistrust on 2 June by trying to qualify it.[c] Both houses now demanded "a clear and satisfactory answer by His Majesty in full Parliament", and on 7 June, Charles capitulated.[24]

Provisions

After setting out a list of individual grievances and statutes that had been broken, the Petition of Right declares that Englishmen have various "rights and liberties", and provides that no person should be forced to provide a gift, loan or tax without an Act of Parliament, that no free individual should be imprisoned or detained unless a cause has been shown, and that soldiers or members of the Royal Navy should not be billeted in private houses without the free consent of the owner.[25]

In relation to martial law, the Petition first repeated the due process chapter of Magna Carta, then demanded its repeal.[d] This clause was directly addressed to the various commissions issued by Charles and his military commanders, restricting the use of martial law except in war or direct rebellion and prohibiting the formation of commissions. A state of war automatically activated martial law; as such, the only purpose for commissions, in their view, was to unjustly permit martial law in circumstances that did not require it.[27]

Aftermath

Charles' acceptance was greeted with widespread public celebrations, including ringing of church bells and lighting of bonfires throughout the country.[28] However, in August, Buckingham was assassinated by a disgruntled former soldier, while the surrender of La Rochelle in October effectively ended the war, and Charles' need for taxes. He dissolved Parliament in 1629, ushering in eleven years of Personal Rule, in which he attempted to regain all the ground lost.[29]

For the rest of his reign, Charles used the same tactics; refusing to negotiate until forced, with concessions seen as temporary and reversed as soon as possible, by force if needed.[30] Once Parliament adjourned, he resumed the policy of imposing unauthorised taxes, then prosecuting opponents using the non-jury Star Chamber. When Parliament and the normal courts quoted the Petition in support of objections to the tax, and the detention of Selden and John Eliot, Charles responded it was not a legal document.[31]

Although confirmed as a legal statute in 1641 by the Long Parliament, debate over who was right continues; however, "it seems impossible to establish conclusively which interpretation (is) correct".[32] Regardless, the Petition has been described as "one of England's most famous constitutional documents",[1] of equal standing to Magna Carta and the 1689 Bill of Rights.[25] It remains in force in the United Kingdom, and much of the Commonwealth.[33] It has been cited in support of the Third Amendment to the United States Constitution,[34] and the Seventh.[35] It is suggested elements appear in the Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Amendment, primarily through the Massachusetts Body of Liberties.[36]

Notes

- ^ The citation of this Act by this short title was authorised by section 5 of, and Schedule 2 to, the Statute Law Revision Act 1948. Due to the repeal of those provisions, it is now authorised by section 19(2) of the Interpretation Act 1978

- ^ These words are printed against this Act in the second column of Schedule 2 to the Statute Law Revision Act 1948, which is headed "Title".

- ^ "The King willeth that right be done according to the laws and customs of the realm; and that the statutes be put in due execution, that the subject may have no just cause of complaint for any wrong or oppression, contrary to their just rights and liberties, to the preservation whereof he holds himself in conscience as well obliged of his just prerogative.[23]

- ^ Neverthelesse of late tyme divers Commissions under your Majesties great Seale have issued forth, by which certaine persons have been assigned and appointed Commissioners with power and authoritie to proceed within the land according to the Justice of Martiall Lawe against such Souldiers or Marriners or other dissolute persons joyning with them as should comitt any murther [sic: murder] robbery felony mutiny or other outrage or misdemeanor whatsoever, and by such sumary course and order as is agreeable to Martiall Lawe and as is used in Armies in tyme of warr to proceed to the tryall and condemnacion of such offenders, and them to cause to be executed and putt to death according to the Lawe Martiall. ... They doe therefore humblie pray your most Excellent Majestie, ... that the aforesaid Commissions for proceeding by Martiall Lawe may be revoked and annulled. And that hereafter no Commissions of like nature may issue forth to any person or persons whatsoever to be executed as aforesaid, lest by colour of them any of your Majesties Subjects be destroyed or put to death contrary to the Lawes and Franchise of the Land.[26]

References

- ^ a b Flemion 1973, p. 193.

- ^ Kishlansky 1999, p. 59.

- ^ Braddick 1996, p. 52.

- ^ Hostettler 1997, p. 119.

- ^ White 1979, p. 190.

- ^ Cust 1985, pp. 209–211.

- ^ Hostettler 1997, p. 125.

- ^ Guy 1982, pp. 291–292.

- ^ Hostettler 1997, p. 126.

- ^ Guy 1982, p. 293.

- ^ Hostettler 1997, p. 127.

- ^ Capua 1977, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Schwoerer 1974, pp. 43–48.

- ^ Baker 2002, p. 167.

- ^ Guy 1982, p. 298.

- ^ Guy 1982, p. 299.

- ^ Guy 1982, p. 307.

- ^ a b White 1979, p. 265.

- ^ Hulme 1935, pp. 304–305.

- ^ Christianson 1994, p. 561.

- ^ White 1979, p. 268, 270.

- ^ Hostettler 1997, pp. 136–137.

- ^ White 1979, p. 270.

- ^ Young 1990, p. 232.

- ^ a b Hostettler 1997, p. 138.

- ^ The Petition of Right [1627].

- ^ Capua 1977, p. 172.

- ^ Hostettler 1997, p. 139.

- ^ Arnold-Baker 2015, p. 270.

- ^ Wedgwood 1958, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Reeve 1986, p. 262.

- ^ White 1979, p. 263.

- ^ Clark 2000, p. 886.

- ^ Kemp 2010, p. 26.

- ^ Samaha 2005, p. 556.

- ^ Bachmann 2000, p. 276.

Works cited

- Arnold-Baker, Charles (2015) [1996]. The Companion to British History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-1389-2883-1.

- Bachmann, Steve (2000). "Starting again with the Mayflower...England's Civil War and America's Bill of Rights". Quinnipiac Law Review. 20 (2). ISSN 1073-8606.

- Baker, John (2002). An Introduction to English Legal History. Butterworths. ISBN 978-0-4069-3053-8.

- Braddick, Michael J (1996). The Nerves of State: Taxation and the Financing of the English State, 1558–1714. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-3871-6.

- Capua, J.V. (1977). "The Early History of Martial Law in England from the Fourteenth Century to the Petition of Right". Cambridge Law Journal. 36 (1): 152–173. doi:10.1017/S0008197300014409. S2CID 144293589.

- Christianson, Paul (1994). "Arguments on Billeting and Martial Law in the Parliament of 1628". The Historical Journal. 37 (3): 539–567. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00014874. ISSN 0018-246X. S2CID 159983961.

- Clark, David (2000). "The Icon of Liberty: The Status and Role of Magna Carta in Australian and New Zealand Law". Melbourne University Law Review. 24 (1). ISSN 0025-8938.

- Cust, Richard (1985). "Charles I, the Privy Council, and the Forced Loan". Journal of British Studies. 24 (2): 208–235. doi:10.1086/385832. JSTOR 175703. S2CID 143537267.

- Flemion, Jess Stoddart (1973). "The Struggle for the Petition of Right in the House of Lords: The Study of an Opposition Party Victory". The Journal of Modern History. 45 (2): 193–210. doi:10.1086/240959. ISSN 0022-2801. S2CID 154907727.

- Guy, J.A. (1982). "The Origin of the Petition of Right Reconsidered". The Historical Journal. 25 (2): 289–312. doi:10.1017/S0018246X82000017. ISSN 0018-246X. S2CID 159977078.

- Hostettler, John (1997). Sir Edward Coke: A Force for Freedom. Barry Rose Law Publishers. ISBN 1-8723-2867-9.

- Hulme, Harold (1935). "Opinion in the House of Commons on the Proposal for a Petition of Right 6 May, 1628". The English Historical Review: 302–306. doi:10.1093/ehr/L.CXCVIII.302. ISSN 0013-8266.

- Kemp, Roger L. (2010). Documents of American Democracy: A Collection of Essential Works. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4210-2.

- Kishlansky, Mark (1999). "Tyranny Denied: Charles I, Attorney General Heath and the Five Knights' Case". The Historical Journal. 42 (1): 53–83. doi:10.1017/S0018246X98008279. ISSN 0018-246X. S2CID 159628863.

- Reeve, L.J. (1986). "The Legal Status of the Petition of Right". The Historical Journal. 29 (2): 257–277. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00018732. ISSN 0018-246X. S2CID 154406219.

- Samaha, Joel (2005). Criminal Justice (7th ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-5346-4557-1.

- Schwoerer, Lois G (1974). 'No Standing Armies!': The Antiarmy Ideology in Seventeenth-Century England. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-1563-8.

- Wedgwood, CV (1958). The King's War, 1641–1647 (2001 ed.). Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-1413-9072-7.

- White, Stephen D. (1979). Sir Edward Coke and the Grievances of the Commonwealth. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1335-4.

- Young, Michael B. (1990). "Charles I and the Erosion of Trust: 1625–1628". Albion. 22 (2): 217–235. doi:10.2307/4049598. ISSN 0095-1390. JSTOR 4049598.

- The Petition of Right [1627]. "The Petition of Right [1627]". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Boynton, Lindsay (1964). "Martial Law and the Petition of Right". The English Historical Review. 79 (311): 255–284. doi:10.1093/ehr/lxxix.cccxi.255.

External links

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- Petition of Right (full text)

- Speech on the Petition of Right delivered to the House of Commons on 3 June 1628, by John Eliot

- "Petition of Right". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- Digital Reproduction of the Original Act on the Parliamentary Archives catalogue