Dodola and Perperuna

Dodola (also spelled Dodole, Dodoli, Dudola, Dudula etc.) and Perperuna (also spelled Peperuda, Preperuda, Preperuša, Prporuša, Papaluga etc.) are rainmaking pagan customs widespread among different peoples in Southeast Europe until the 20th century, found in Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Kosovo, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Romania, and Serbia. It is still practiced in remote Albanian ethnographic regions, but only in rare events, when the summer is dry and without atmospheric precipitation.[1][2]

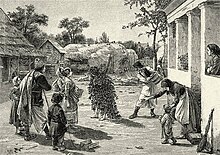

The ceremonial ritual is an analogical-imitative magic rite that consists of singing and dancing done by young girls or boys in processions following a main performer who is dressed with fresh branches, leaves and herbs, with the purpose of invoking rain, usually practiced in times of droughts, especially in the summer season, when drought endangers crops and pastures, even human life itself.

According to one interpretation, the custom could have Slavic origin and be related to Slavic god Perun, and Perperuna could have been a Slavic goddess of rain, and the wife of the supreme deity Perun (god of thunder and weather in the Slavic pantheon). Recent research criticize invention of a Slavic female goddess, and indicate as possible both Slavic and old-Balkan influences. In Albanian ritual songs are invoked Dielli (the Sun), Perëndi (the Sky, or deity of weather), and Ilia (Elijah, who in Christianized Albanian and South Slavic folklore has replaced the Sun god and the thunder or weather god, Drangue and Perun).

Names

[edit]Περπερούνα περπατεί / Perperouna perambulates

Κή τόν θεό περικαλεί / And to God prays

Θέ μου, βρέξε μια βροχή / My God, send a rain

Μιἁ βροχή βασιλική / A right royal rain

Οσ ἀστἀχυα ς τἀ χωράΦια / That as many (as are there) ears of corn in the fields

Τόσα κούτσουρα ς τ ἁμπέλια / So many stems (may spring) on the vines

Shatista near Siatista, Western Macedonia, Ottoman Empire, 1903[3]

Rainmaking rites are generally called after the divine figure invoked in the ritual songs, as well as the boy or girl who perform the rite, who are called with different names among different peoples (South Slavs, Albanians, Greeks, Hungarians, Moldovans, Romanians, Vlachs or Aromanians, including regions of Bukovina and Bessarabia).[4] The custom's Slavic prototype name is *Perperuna, with variations:[5][6][7][8][9]

- Preperuna, Peperuna, Preperuda/Peperuda, Pepereda, Preperuga/Peperuga, Peperunga, Pemperuga in Bulgaria and North Macedonia

- Prporuša, Parparuša, Preporuša/Preporuča, Preperuša, Barburuša/Barbaruša in Croatia

- Perperouna, Perperinon, Perperouga, Parparouna in Greece

- Pirpirunã among Aromanians

- Dodola (including Serbia among previous countries, with local variants Dodole, Dudola, Dudula, Dudule, Dudulica, Doda, Dodočka, Dudulejka, Didjulja, Dordolec/Durdulec etc.).

In Albanian the rainmaking ritual is also called riti i ndjelljes së shiut ("Rain-Invoking Ritual"), riti i thirrjes së shiut ("Rain-Calling Ritual" or "Rite of Calling the Rain") or simply thirrja e shiut ("Call of the Rain"), riti i thatësisë ("Drought Ritual"), as well as riti me dordolecin or riti i dordolecit ("Dordoleci Ritual"), riti i dodolisë ("Dodoli Ritual").[1][2][11][12]

Etymology

[edit]Some scholars consider all the Balkan names of the type per-, perper-, peper-, papar-, etc. to be taboo-alternations to "avoid profaning the holy name" of the pagan Indo-European god *Perkʷūnos.[13][5] According to Roman Jakobson and others perperuna is formed by reduplication of root "per-" (to strike/beat).[5][14][15] Those with root "peper-", "papar-" and "pirpir-" were changed accordingly modern words for pepper-tree and poppy plant,[5][16] possibly also perper and else.[17][18]

Dimitar Marinov derived it from Bulgarian word for butterfly where in folk beliefs has supernatural powers related to rain,[19] but according to Jakobson the mythological context of the customs and links explains the Bulgarian entomological names.[20] Michail Arnaudov derived it from Slavic verb "pršiti" (spray).[19] Petar Skok considered prporuša a metaphorical derivation from Slavic prpor/pŕpa (hot ash), pórusa ("when water is poured on burning ash"[21]).[22] Stanisław Urbańczyk and Michal Łuczyński put into question Jakobson's theonymic derivation, deriving instead from Proto-Slavic *perpera, *perperъka (in Polish przepiórka), name for Common quail, which has a role in Polish harvest rituals and the name of the bride in the wedding dance.[23][24] These are also related to *pъrpati (onomatopoeic), cf. Polish dial. perpotać, perpac, Old East Slavic poropriti.[24]

The name Dodola has been suggested to be a cognate to the Lithuanian Dundulis, a word for "thunder" and another name of the Baltic thunder-god Perkūnas.[14][25] It is also hypothesised to be distantly related to Greek Dodona and Daedala.[26][27] Bulgarian variant Didjulja is similar to alleged Polish goddess Dzidzilela, and Polish language also has verb dudnić ("to thunder").[28]

The uncertainty of the etymologies provided by scholars leads to a call for a "detailed and in-depth comparative analysis of formulas, set phrases and patterns of imagery in rainmaking songs from all the Balkan languages".[29]

Origin

[edit]The rainmaking practice is a shared tradition among Balkan peoples, and it is not clear who borrowed it from whom.[30] The fact so similar customs in the Balkans are known by two different names the differences are considered not to be from the same time period and ethnic groups.[31] Similar customs outside the Balkans have been observed in the Caucasus, Middle East, and North Africa.[32][33][34][35] William Shedden-Ralston noted that Jacob Grimm thought Perperuna/Dodola were "originally identical with the Bavarian Wasservogel and the Austrian Pfingstkönig" rituals.[36]

Ancient rainmaking practices have been widespread Mediterranean traditions, already documented in the Balkans since Minoan and Mycenaean times.[37][38] There is a lack of any strong historical evidence for a link between the figures and practices of the ancient times and those that survided to the end of the 20th century, however, according to Richard Berengarten, if seen as "typologically parallel" practices in the ancient world, they may be interpretable at least as forerunners, even if not as direct progenitors of the modern Balkan rainmaking customs.[37]

In the scholarship is usually considered they have a mythological and etymological Slavic origin related to Slavic thunder-god Perun,[47] and became widespread in the Southeastern Europe with the Slavic migration (6th-10th century).[48][49][50] According to the Slavic theory, it is a (Balto-)Slavic heritage of Proto-Indo-European origin related to Slavic thunder-god Perun. It has parallels in ritual prayers for bringing rain in times of drought dedicated to rain-thunder deity Parjanya recorded in the Vedas and Baltic thunder-god Perkūnas, cognates alongside Perun of Proto-Indo-European weather-god Perkwunos.[51] The same ritual in an early medieval Ruthenian manuscript is related to East Slavic deity Pereplut.[52][5][53] According to Jakobson, Novgorod Chronicle ("dožd prapruden") and Pskov Chronicle ("dožd praprudoju neiskazaemo silen") could have "East Slavic trace of Peperuda calling forth the rain", and West Slavic god Pripegala reminds of Preperuga/Prepeluga variation and connection with Perun.[5][54] Serbo-Croatian archaic variant Prporuša and verb prporiti se ("to fight") also have parallels in Old Russian ("porъprjutъsja").[14]

According to another interpretation the name Perperuna can be identified as the reduplicated feminine derivative of the name of the male god Perun (per-perun-a), being his female consort, wife and goddess of rain Perperuna Dodola, which parallels the Old Norse couple Fjörgyn–Fjörgynn and the Lithuanian Perkūnas–Perkūnija.[28][25][55][56][57] Perun's battle against Veles because of Perperuna/Dodola's kidnapping has parallels in Zeus saving of Persephone after Hades carried her underground causing big drought on Earth, also seen in the similarity of the names Perperuna and Persephone.[56][58][21] Recent research criticize invention of a Slavic female goddess.[24]

Another explanation for the variations of the name Dodola is relation to the Slavic spring goddess (Dido-)Lada/Lado/Lela,[36] some scholars relate Dodole with pagan custom and songs of Lade (Ladarice) in Hrvatsko Zagorje (so-called "Ladarice Dodolske"),[59][60][61] and in Žumberak-Križevci for the Preperuša custom was also used term Ladekarice.[62][63]

Other scholars like Vitomir Belaj, due to the geographical distribution, consider that the rainmaking ritual could also have Paleo-Balkan origin,[64][65] or formed separate of worship of Perun but could be etymologically related.[44] One theory, in particular, argues that Slavic deity Perun and Perperuna/Dodola customs are of Thracian origin,[66][67][68][69] however, the name of the Slavic thunder-god Perun is commonly accepted to be formed from the Proto-Slavic root *per "to strike" attached to the common agent suffix -unŭ, explained as "the Striker".[70] The Romanian-Aromanian and Greek ethnic origin was previously rejected by Alan Wace, Maurice Scott Thompson, George Frederick Abbott among others.[71]

Ritual

[edit]

Perperuna and Dodola are considered very similar pagan customs with common origin,[72][73] with main difference being in the most common gender of the central character (possibly related to social hierarchy of the specific ethnic or regional group[74]), lyric verses, sometimes religious content, and presence or absence of a chorus.[75] They essentially belong to rituals related to fertility, but over time differentiated to a specific form connected with water and vegetation.[76] They represent a group of rituals with a human collective going on a procession around houses and fields of a village, but with a central live character which differentiates them from other similar collective rituals in the same region and period (Krstonoše, Poklade, Kolade, German, Ladarice, those during Jurjevo and Ivandan and so on).[77][78][79] In the valley of Skopje in North Macedonia the Dodola were held on Thursday which was Perun's day.[80] In Hungary the ritual was usually held on St. George's Day.[81] The core of the song always mentions a type of rain and list of regional crops.[82] The first written mentions and descriptions of the pagan custom are from the 18th century by Dimitrie Cantemir in Descriptio Moldaviae (1714/1771, Papaluga),[9][83] then in a Greek law book from Bucharest (1765, it invoked 62nd Cannon to stop the custom of Paparuda),[9][84] and by the Bulgarian hieromonk Spiridon Gabrovski who also noted to be related to Perun (1792, Peperud).[65][85]

South Slavs and non-Slavic peoples alike used to organise the Perperuna/Dodola ritual in times of spring and especially summer droughts, where they worshipped the god/goddess and prayed to him/her for rain (and fertility, later also asked for other field and house blessings). The central character of the ceremony of Perperuna was usually a young boy, while of Dodola usually a young girl, both aged between 10–15 years. Purity was important, and sometimes to be orphans. They would be naked, but were not anymore in latest forms of 19-20th century, wearing a skirt and dress densely made of fresh green knitted vines, leaves and flowers of Sambucus nigra, Sambucus ebulus, Clematis flammula, Clematis vitalba, fern and other deciduous shrubs and vines, small branches of Tilia, Oak and other. The green cover initially covered all body so that the central person figure was almost unrecognizable, but like the necessity of direct skin contact with greenery it also greatly decreased and was very simple in modern period. They whirled and were followed by a small procession of children who walked and danced with them around the same village and fields, sometimes carrying oak or beech branches, singing the ritual prayer, stopping together at every house yard, where the hosts would sprinkle water on chosen boy/girl who would shake and thus sprinkle everyone and everything around it (example of "analogical magic"[9]), hosts also gifted treats (bread, eggs, cheese, sausages etc., in a later period also money) to children who shared and consumed them among them and sometimes even hosts would drink wine, seemingly as a sacrifice in Perun's honor.[86][87][88][89][90][91][92] The chosen boy/girl was called by one of the name variants of the ritual itself, however in Istria was also known as Prporuš and in Dalmatia-Boka Kotorska as Prpac/Prpats and both regions his companions as Prporuše,[36][80][86][93] while at Pirot and Nišava District in Southern Serbia near Bulgarian border were called as dodolće and preperuđe, and as in Macedonia both names appear in the same song.[94][95]

By the 20th century once common rituals almost vanished in the Balkans, although rare examples of practice can be traced until 1950-1980s and remained in folk memory. In some local places, like in Albania, can be observed as rare events even in the 21st century.[1][2]

The main reason is the development of agriculture and consequently lack of practical need for existence of mystical connection and customs with nature and weather. Christian church also tried to diminish pagan beliefs and customs, resulting in "dual belief" (dvoeverie) in rural populations, a conscious preservation of pre-Christian beliefs and practices alongside Christianity. Into customs and songs were mixed elements from other rituals including Christianity, but they also influenced the creation of Christian songs and prayers invoking the rain which were used as a close Christian alternative (decline was reportedly faster among Catholics[96]).[97][98] According to Velimir Deželić Jr. in 1937, it was an old custom that "Christians approved it, took it over and further refined it. In the old days, Prporuša were very much like a pious ritual, only later the leaders - Prpac - began to boast too much, and Prporuše seemed to be more interested in gifts than beautiful singing and prayer".[99] Depending on region, instead of village boys and girls the pagan ritual by then was mostly done by migrating Romani people from other villages and for whom it became a professional performance motivated by gifts, sometimes followed by financially poor members from other ethnic groups.[97][98][100][101][102] Due to Anti-Romani sentiment, the association with Romani also caused repulsion, shame and ignorance among last generations of members of ethnic groups who originally performed it.[103] Eventually it led to a dichotomy of identification with own traditional heritage, Christianity and stereotypes about Romani witchcraft.[104]

In the present days, older generations of Albanians demonstrate the common practice of rainmaking rituals in their life, but newer generations generally see them as something applied in the past, a tradition that their parents have gone through. Nevertheless, elders still accompany processions of boys and girls, who perform the rainmaking rite dressed with their best traditional clothing except for the main boy or girl, who is dressed entirely in fresh branches, leaves and herbs.[1][2][12] Public exhibitions of the ritual are usually performed during Albanian festivals, often for the local audience, but also in the Gjirokastër National Folk Festival, one of the most important events of Albanian culture.[105]

Perperuna songs

[edit]Ioan Slavici reported in 1881 that the custom of Paparuga was already "very disbanded" in Romania.[106] Stjepan Žiža in 1889/95 reported that the once common ritual almost vanished in Southwestern and Central-Eastern Istria, Croatia.[107] Ivan Milčetić recorded in 1896 that the custom of Prporuša also almost vanished from the North Adriatic island of Krk, although almost recently it was well known in all Western parts of Croatia, while in other parts as Dodola.[108] Croatian linguist Josip Ribarić recorded in 1916 that it was still alive in Southwestern Istria and Ćićarija (and related it to the 16th century migration from Dalmatia of speakers of Southwestern Istrian dialect).[86] On island of Krk was also known as Barburuša/Barbaruša/Bambaruša (occurrence there is possibly related to the 15th century migration which included besides Croats also Vlach-Istro-Romanian shepherds[109]).[110][111] It was also widespread in Dalmatia (especially Zadar hinterland, coast and islands), Žumberak (also known as Pepeluše, Prepelice[96]) and Western Slavonia (Križevci).[36][73][100][111][112][113] It was held in Istria at least until the 1950s,[114] in Žumberak until the 1960s,[115] while according to one account in Jezera on island Murter the last were in the late 20th century.[116] In Serbia, Perperuna was only found in Kosovo, Southern and Eastern Serbia near Bulgarian border.[117] According to Natko Nodilo the discrepancy in distribution between these two countries makes an idea that originally Perperuna was Croatian while Dodola was Serbian custom.[118] Seemingly it was not present in Slovenia, Northern Croatia, almost all of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro (only sporadically in Boka Kotorska).[119] Luka Jovović from Virpazar, Montenegro reported in 1896 that in Montenegro existed some koleda custom for summer droughts, but was rare and since 1870s not practiced anymore.[108]

According to Albanian folk beliefs, the Sun (Dielli) makes the sky cloudy or clears it up.[120][121] Albanians used to invoke the Sun with rainmaking and soil fertility rituals. In rainmaking rituals from the Albanian Ionian Sea Coast, Albanians used to pray to the Sun, in particular facing Mount Shëndelli (Mount "Holy Sun"), by invoking the names Dielli, Shën Dëlliu, Ilia or Perëndia. Children used to dress a boy with fresh branches, calling him dordolec. A typical invocation song repeated three times during the ritual was:[121] Afterwards, people used to say: Do kemi shi se u nxi Shëndëlliu ("We will have rain because Shëndëlliu went dark").[121] The Sun used to be also invoked when reappearing after the rain, prayed for increased production in agriculture.[121]

| Bulgaria[122] | Albania[123][124] | Croatia-Krk (Dubašnica, 1896[108]) |

Croatia-Istria (Vodice, 1916[86]) |

Croatia-Istria (Čepić, 1896[108]/Štifanići near Baderna, 1906/08[125]) |

Croatia-Dalmatia (Ražanac, 1905[126]) |

Croatia-Dalmatia (Ravni Kotari, 1867[127]) |

Croatia-Žumberak (Pavlanci, 1890[128]) |

|

Letela e peperuda |

Rona-rona, Peperona |

Prporuša hodila |

Prporuše hodile |

Preporuči hodili / Prporuše hodile |

Prporuše hodile |

Prporuše hodile |

Preperuša odila |

Dodola songs

[edit]The oldest record for Dodole rituals in Macedonia is the song "Oj Ljule" from Struga region, recorded in 1861.[129] The Dodola rituals in Macedonia were actively held until the 1960s.[130] In Bulgaria the chorus was also "Oj Ljule".[131] The oldest record in Serbia was by Vuk Karadžić (1841),[117] where was widespread all over the country and held at least until 1950/70s.[41][132] In Croatia was found in Eastern Slavonia, Southern Baranja and Southeastern Srijem.[100][133][119][134][135] August Šenoa in his writing about the travel to Okić-grad near Samobor, Croatia mentioned that saw two dodole.[136] To them is related the custom of Lade/Ladarice from other parts of Croatia, having chorus "Oj Lado, oj!" and similar verses "Molimo se višnjem Bogu/Da popuhne tihi vjetar, Da udari rodna kiša/Da porosi naša polja, I travicu mekušicu/Da nam stada Lado, Ugoje se naša stada".[59][60][61]

| Macedonia (Struga, 1861[129]) |

Serbia (1841[127][137]) |

Serbia (1867[127]) |

Serbia (1867[127]) |

Croatia-Slavonia (Đakovo[61]) |

Croatia-Slavonia (Đakovo, 1957[138]) |

Croatia-Srijem (Tovarnik, 1979[139]) |

|

Otletala preperuga, oj ljule, oj! |

Mi idemo preko sela, |

Molimo se višnjem Bogu, |

Naša doda Boga moli, |

Naša doda moli Boga |

Naša dojda moli boga da kiša pada |

Naša doda moli Boga |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Qafleshi 2011, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b c d Ministria 2014, p. 66.

- ^ Abbott, George Frederick (1903). Macedonian Folklore. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 119.

- ^ Ḱulavkova 2020, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e f Gimbutas 1967, p. 743.

- ^ Evans 1974, p. 100.

- ^ Jakobson 1985, p. 22–24:Mythological associations linked with the butterfly (cf. her Serbian name Vještica) also explain the Bulgarian entomological names peperuda, peperuga

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 80, 93.

- ^ a b c d Puchner 2009, p. 346.

- ^ Norris 1993, p. 34.

- ^ a b Tirta 2004, pp. 310–312.

- ^ a b Halimi, Halimi-Statovci & Xhemaj 2011, pp. 2–6, 32–43.

- ^ Evans 1974, p. 116.

- ^ a b c Jakobson 1985, p. 23.

- ^ a b Katičić, Radoslav (2017). Naša stara vjera: Tragovima svetih pjesama naše pretkršćanske starine [Our Old Faith: Tracing the Sacred Poems of Our Pre-Christian Antiquity] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Ibis Grafika, Matica hrvatska. p. 105. ISBN 978-953-6927-98-2.

- ^ Puchner 2009, p. 348.

- ^ Puchner, Walter (1983). "Бележки към ономатологията и етимологиятана българските и гръцките названия на обреда за дъжд додола/перперуна" [Notes on the Onomatology and the Etymology of Bulgarian and Greek Names for the Dodola / Perperuna Rite]. Bulgarian Folklore (in Bulgarian). IX (1): 59–65.

- ^ Puchner 2009, p. 347–349.

- ^ a b Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 94.

- ^ Jakobson 1985, p. 22:Mythological associations linked with the butterfly (cf. her Serbian name Vještica) also explain the Bulgarian entomological names peperuda, peperuga

- ^ a b Burns 2008, p. 232.

- ^ Skok, Petar (1973). Etimologijski rječnik hrvatskoga ili srpskoga jezika: poni-Ž (in Serbo-Croatian). Vol. 3. Zagreb: JAZU. p. 55.

- ^ Urbańczyk 1991, p. 150.

- ^ a b c Łuczyński 2020, p. 141.

- ^ a b Puhvel 1987, p. 235.

- ^ Evans 1974, p. 127–128.

- ^ Dauksta, Dainis (2011). "From Post to Pillar – The Development and Persistence of an Arboreal Metaphor". New Perspectives on People and Forests. Springer. p. 112. ISBN 978-94-007-1150-1.

- ^ a b Jakobson 1985, p. 22–23.

- ^ Burns 2008, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Wachtel 2008:Anthropologists have noted shared traditions as well, such as a rainmaking ritual in which a young woman covered in a costume of leavs would sing and dance through the village: this ritual was practiced among Greek, Albanian, Romanian, and Slavic speakers throughout the region, and it is not clear who borrowed it from whom.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 93.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 84, 93.

- ^ Kulišić 1979, p. 108.

- ^ Başgöz, İlhan (2007). "Rain Making Ceremonies in Iran". Iranian Studies. 40 (3): 385–403. doi:10.1080/00210860701390588. JSTOR 4311905. S2CID 162315052.

Type II in the classification (that is, the procession with a doll, or chomcha gelin, and its sub-group, which consists in a real child's proceeding through the neighborhood) ... Although the same ceremony is performed in other parts of Turkey, the ladle bride is given different names: Bodi Bodi among the Karalar Turkmen tribe in Adana province, Dodo or Dodu in Kars ... As the type spreads toward the west, sub-type (a) becomes dominant and (b) disappears. In Bulgaria, the girl who visits the houses during the ceremony is called doldol or Perperuga.46 In Greece, the ceremony is sometimes incorporated into the Epiphany, the ritual throwing of the cross into a river, or sometimes is performed as an independent rain ritual.47 In Yugoslavia, the Turks, Serbians, and the Albanians practice the ritual, naming it dodola or dodoliče (little dodola).48 The ritual is known in Hungary and is performed there under the name of doldola, being especially common in villages inhabited by Gypsies and Serbians.49 The custom has spread to Rumania, but there the chomcha gelin is replaced by a coffin with a clay figure in it. This is reminiscent of Type II in Iran.50 The chomcha gelin is also observed in Iraq among the Kerkuk Turkmens, who call it "the bride with ladle" (Chomchalı Gelin).51 In Syria, the Arabs call the doll Umm al-Guys ("mother of rain").52 The Christians in Syria practice the ceremony and call the doll "the bride of God".53 In North Africa, the doll is called "the mother of Bangau",54 and a similar symbol carried during the ritual is called Al Gonja.55 In Uzbekistan, Turks and Tajiks perform the ritual, calling the doll suskhatun (probably meaning "water woman").56

- ^ Chirikba, Viacheslav (2015). "Between Christianity and Islam: Heathen Heritage in the Caucasus". Studies on Iran and The Caucasus: In Honour of Garnik Asatrian. Leiden: Brill. pp. 169–171. ISBN 978-90-04-30206-8.

Thus, during the festival welcoming the spring, the Avars made ... In the ritual of summoning rains there figured a specially made doll called Dodola ... The Dagestan doll Dodola and the ritual strikingly resemble the Balkan rituals for summoning rain, whereby girls called Dodola would undressed and put on leaves, flowers and herbs to perform the rainmaking ceremony. The Balkan Dodola is regarded as being connected with the Slavic cult of the thunder-god Perun (cf. Tokarev 1991: 391).

- ^ a b c d Shedden-Ralston, William Ralston (1872). The Songs of the Russian People: As Illustrative of Slavonic Mythology and Russian Social Life. London: Ellis & Green. pp. 227–229.

- ^ a b Burns 2008, pp. 228–231.

- ^ Håland 2001, pp. 197–201.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, pp. 93–94:Ovakav obred za kišu poznat je i u Madžarskoj. Analizirao ga je Z. Ujvary te je u svojoj studiji citirao mnoge madžarske autore koji su o tome pisali. Prema njegovu mišljenju, običaj se tamo proširio pod utjecajem Slavena i Rumunja ... M. S. Thompson, međutim, misli da riječ "perperuna" potječe od imena slavenskog boga Peruna, boga gromovnika ... Teoriju o slavenskom porijeklu ovog običaja prihvatili su osim M. S. Thompsona još i G. F. Abbott i E. Fischer.

- ^ Gieysztor 2006, p. 89, 104–106.

- ^ a b Zečević, Slobodan (1974). Elementi naše mitologije u narodnim obredima uz igru (in Serbian). Zenica: Muzej grada Zenice. pp. 125–128, 132–133.

- ^ Institut za književnost i umetnost (Hatidža Krnjević) (1985). Rečnik književnih termina [Dictionary of literary terms] (in Serbian). Beograd: Nolit. pp. 130, 618. ISBN 978-86-19-00635-4.

- ^ Sikimić, Biljana (1996). Etimologija i male folklorne forme (in Serbian). Beograd: SANU. pp. 85–86.

О vezi Peruna i prporuša up. Ivanov i Toporov 1974: 113: можно думать об одновременной связи имени nеnеруна - nрnоруша как с обозначением nорошения дождя, его распыления (ср. с.-хорв. ирпошuмu (се), nрnошка и Т.Д.; чешск. pršeti, prch, prš), так и с именем Громовержца. Связъ с порошением дождя представляется тем более вероятной, что соответствующий глагол в ряде индоевропейских язЪП<ов выступает с архаическим удвоением". Za etimologiju sh. ргроrušа up. i Gavazzi 1985: 164.

- ^ a b Belaj 2007, p. 80, 112.

- ^ Dragić 2007, p. 80, 112.

- ^ Lajoye 2015, p. 114.

- ^ [39][15][40][41][42][43][44][45][46]

- ^ Gimbutas 1967, p. 743:The names applied to the Balkan rain-ceremonies and to those who perform them suggest, by the modest, degree of variation from one another, by the large number of different variants, and their distribution (not only throughout Romania but in Albania and Greek Epirus and Macedonia), the diffusion of a Slavic ritual linked with the name of Perun in any one of its numerous minor variants.

- ^ Jakobson 1985, pp. 22, 24:The ritual call for rain was transmitted long ago from the Balkan Slavs to neighboring peoples, who evidently preserved the original form of the mythological name ... But even if one leaves aside the late, conjectural echoes of Perun's name, one is still forced to conclude that his cult had wide dissemination and deep roots in Slavic paganism, a fact that is clearly reflected not only in the texts, but also in onomastics, as well as in the folklore of the Slavs and their neighbors.

- ^ Zaroff, Roman (1999). "Organized pagan cult in Kievan Rus': The invention of foreign elite or evolution of local tradition?". Studia mythologica Slavica. 2: 57. doi:10.3986/sms.v2i0.1844.

As a consequence of the relatively early Christianisation of the Southern Slavs, there are no more direct accounts in relation to Perun from the Balkans. Nevertheless, as late as the first half of the 12th century, in Bulgaria and Macedonia, peasants performed a certain ceremony meant to induce rain. A central figure in the rite was a young girl called Perperuna, a name clearly related to Perun. At the same time, the association of Perperuna with rain shows conceptual similarities with the Indian god Parjanya. There was a strong Slavic penetration of Albania, Greece and Romania, between the 6th and 10th centuries. Not surprisingly the folklore of northern Greece also knows Perperuna, Albanians know Pirpirúnă, and also the Romanians have their Perperona.90 Also, in a certain Bulgarian folk riddle the word perušan is a substitute for the Bulgarian word гърмомеҽица (grmotevitsa) for thunder.91 Moreover, the name of Perun is also commonly found in Southern Slavic toponymy. There are places called: Perun, Perunac, Perunovac, Perunika, Perunićka Glava, Peruni Vrh, Perunja Ves, Peruna Dubrava, Perunuša, Perušice, Perudina and Perutovac.92

- ^ Jakobson 1985, p. 6–7, 21, 23.

- ^ Jakobson 1955, p. 616.

- ^ Jakobson 1985, p. 23–24.

- ^ Jakobson 1985, p. 24.

- ^ Jackson 2002, p. 70.

- ^ a b York, Michael (1993). "Toward a Proto-Indo-European vocabulary of the sacred". Word. 44 (2): 240, 251. doi:10.1080/00437956.1993.11435902.

- ^ Ḱulavkova 2020, p. 19–20a:The Balkan rainmaking customs themselves go by different names. They are usually referred to as the Dodola or Peperuga(Peperuda) rituals, after the name of the goddess of rain, wife or consort of the Slavic sky-god Perun ... According to others, these rain-rituals derive specifically from Slavic languages, and the names Peperuda, Peperuga, Peperuna, and Perperuna are cognate with that of the storm-god Perun.

- ^ Evans 1974, p. 116–117.

- ^ a b Čubelić, Tvrtko (1990). Povijest i historija usmene narodne književnosti: historijske i literaturno-teorijske osnove te genološki aspekti: analitičko-sintetički pogledi (in Croatian). Zagreb: Ante Pelivan i Danica Pelivan. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-86-81703-01-4.

- ^ a b Dragić 2007, p. 279, 283.

- ^ a b c Dragić, Marko (2012). "Lada i Ljeljo u folkloristici Hrvata i slavenskom kontekstu" [Lada and Ljeljo in the folklore of Croats and Slavic context]. Zbornik radova Filozofskog fakulteta u Splitu (in Croatian). 5: 45, 53–55.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 80–81.

- ^ Muraj 1987, p. 160–161.

- ^ Kulišić 1979, p. 205.

- ^ a b Belaj 2007, p. 80.

- ^ Dimitǔr Dechev, Die thrakischen Sprachreste, Wien: R.M. Rohrer, 1957, pp. 144, 151

- ^ Sorin Paliga (2003). "Influenţe romane și preromane în limbile slave de sud" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 28, 2013.

- ^ Dragnea, Mihai (2014). "The Thraco-Dacian Origin of the Paparuda/Dodola Rain-Making Ritual". Brukenthalia Acta Musei (4): 18–27.

- ^ Ḱulavkova 2020, p. 19–20b:According to some researchers ... these pagan rites of worship are thought to be of Thracian origin ... According to other beliefs, Perun, Perin, or Pirin was the supreme deity of the Thracians.

- ^ West 2007, p. 242.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 93–94.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 75, 78, 93, 95.

- ^ a b Vukelić, Deniver (2010). "Pretkršćanski prežici u hrvatskim narodnim tradicijam" [Pre-Christian belief traces in Croatian folk traditions]. Hrvatska revija (in Croatian). No. 4. Matica hrvatska. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 85, 95.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 84–85, 90.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 73, 75–76, 91.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 74–75, 80.

- ^ Dragić 2007, p. 276.

- ^ Puchner 2009, p. 289, 345.

- ^ a b Dragić 2007, p. 291.

- ^ T., Dömötör (1967). "Dodola".

- ^ Puchner, Walter (2016). Die Folklore Südosteuropas: Eine komparative Übersicht (in German). Böhlau Verlag Wien. p. 65. ISBN 978-3-205-20312-4.

- ^ Cantemir, Dimitrie (1771). Descriptio antiqui et hodierni status Moldaviae (in German). Frankfurt, Leipzig. pp. 315–316.

Im Sommer, wenn dem Getreide wegen der Dürre Gefabr bevorzustehen fcheinet, ziehen die Landleute einem kleinen Ragdchen, welches noch nicht über zehen Jahr alt ist, ein Hemde an, welches aus Blattern von Baumen und Srantern gemacht wird. Alle andere Ragdchen und stnaben vol gleiechem Alter folgen ihr, und siehen mit Tanzen und Singen durch die ganze Racharfchaft; wo sie aber hin komuien, da pflegen ihnen die alten Weiber kalt Wasser auf den Stopf zu gieffen. Das Lied, welches fie fingen, ist ohngefähr von folegendem Innbalte: "Papaluga! steige nech dem Himmel, öffne feine Thüren, fend von oben Regen ber, daß der Roggen, Weizen, Hirfe u. f. w. gut wachsen."

- ^ Puchner, Walter (2017). "2 - Byzantium High Culture without Theatre or Dramatic Literature?". Greek Theatre between Antiquity and Independence: A History of Reinvention from the Third Century BC to 1830. Cambridge University Press. p. 73. doi:10.1017/9781107445024.004. ISBN 978-1-107-44502-4.

...in 1765, a Greek law book from Bucharest quotes the 62nd Canon of the Trullanum in order to forbid public dancing by girls in a custom well known throughout the Balkans as 'paparuda', 'perperuna' or 'dodole', a ritual processional rain dance.

- ^ Габровски, Спиридон Иеросхимонах (1900). История во кратце о болгарском народе славенском. Сочинися и исписа в лето 1792. София: изд. Св. Синод на Българската Църква. pp. 14.

- ^ a b c d Ribarić, Josip (2002) [1916]. O istarskim dijalektima: razmještaj južnoslavenskih dijalekata na poluotoku Istri s opisom vodičkog govora (in Croatian). Pazin: Josip Turčinović. pp. 84–85, 206. ISBN 953-6262-43-6.

- ^ Gimbutas 1967, p. 743–744.

- ^ Evans 1974, p. 100, 119.

- ^ Jakobson 1985, p. 21, 23.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 74–77, 83–93.

- ^ Muraj 1987, p. 158–163.

- ^ Dragić 2007, p. 290–293.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 76, 80.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 79, 95.

- ^ Burns 2008, p. 220, 222:The finely documented account by Đorđević of a version of the Balkan rainmaking custom, performed near the River Morava in south-eastern Serbia near the Bulgarian border ... Fly, fly, peperuga/Oh, dodolas, Dear Lord!

- ^ a b Muraj 1987, p. 161.

- ^ a b Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 77, 91–93.

- ^ a b Predojević 2019, p. 581, 583, 589–591.

- ^ Deželić Jr., Velimir (1937). Kolede: Obrađeni hrvatski godišnji običaji [Kolede: Examined Croatian annual customs] (in Croatian). Hrvatsko književno društvo svetog Jeronima. p. 70.

Ljeti, kad zategnu suše, pošle bi našim selima Prporuše moliti od Boga kišu. Posvuda su Hrvatskom išle Prporuše, a običaj je to prastar — iz pretkršćanskih vremena — ali lijep, pa ga kršćani odobrili, preuzeli i još dotjerali. U stara vremena Prporuše su bile veoma nalik nekom pobožnom obredu, tek poslije su predvodnici — Prpci— počeli suviše lakrdijati, a Prporušama ko da je više do darova, nego do lijepa pjevanja i molitve.

- ^ a b c Horvat, Josip (1939). Kultura Hrvata kroz 1000 godina [Culture of Croats through 1000 years] (in Croatian). Zagreb: A. Velzek. pp. 23–24.

- ^ Kovačević, Ivan (1985). Semiologija rituala [Semiology of ritual] (in Serbian). Beograd: Prosveta. p. 79.

- ^ Dragić 2007, p. 278, 290.

- ^ Predojević 2019, p. 583–584, 589.

- ^ Predojević 2019, p. 581–582, 584.

- ^ Sela 2017, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Nodilo 1981, p. 51.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 78.

- ^ a b c d Milčetić, Ivan (1896). "Prporuša". Zbornik za narodni život i običaje južnih Slavena. 1. Belgrade: JAZU: 217–218.

Čini mi se da je već nestalo prporuše i na otoku Krku, a bijaše još nedavno poznata svuda po zapadnim stranama hrvatskog naroda, dok je po drugim krajevima živjela dodola. Nego i za dodolu već malo gdje znadu. Tako mi piše iz Vir‐Pazara g. L. Jovović, koga sam pitao, da li još Crnogorci poznaju koledu...

- ^ Zebec 2005, p. 68–71, 248.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 80.

- ^ a b Zebec 2005, p. 71.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 78, 80–81.

- ^ Dragić 2007, p. 291–293.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 82.

- ^ Muraj 1987, p. 165.

- ^ Dragić 2007, p. 292.

- ^ a b Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 79.

- ^ Nodilo 1981, p. 50a:Po tome, pa i po različitome imenu za stvar istu, mogao bi ko pomisliti, da su dodole, prvim postankom, čisto srpske, a prporuše hrvatske. U Bosni, zapadno od Vrbasa, zovu se čaroice. Kad bi ovo bilo hrvatski naziv za njih, onda bi prporuše bila riječ, koja k nama pregje od starih Slovenaca.

- ^ a b Muraj 1987, p. 159.

- ^ Tirta 2004, pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b c d Gjoni 2012, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Антонова, Илонка Цанова (2015). Календарни празници и обичаи на българите [Calendar holidays and customs of the Bulgarians] (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Издателство на Българската академия на науките "Проф. Марин Дринов". pp. 66–68. ISBN 978-954-322-764-8.

- ^ Gjoni 2012, p. 85.

- ^ Pipa, Arshi (1978). Albanian Folk Verse: Structure and Genre. O. Harrassowitz. p. 58. ISBN 3-87828-119-6.

- ^ Ribarić, Josip (1992). Tanja Perić-Polonijo (ed.). Narodne pjesme Ćićarije (in Croatian). Pazin: Istarsko književno društvo "Juraj Dobrila". pp. 11, 208.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d Karadžić, Vuk Stefanović (1867). Život i običaji naroda srpskoga [Life and customs of Serbian nation] (in Serbian). Vienna: A. Karacić. pp. 61–66.

- ^ Muraj 1987, p. 164.

- ^ a b Miladinovci (1962). Зборник (PDF). Skopje: Kočo Racin. p. 462. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-16.

- ^ Veličkovska, Rodna (2009). Музичките дијалекти во македонското традиционално народно пеење: обредно пеење [Musical dialects in the Macedonian traditional folk singing: ritual singing] (in Macedonian). Skopje: Institute of folklore "Marko Cepenkov". p. 45.

- ^ Nodilo 1981, p. 50b.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 77–78, 86, 88.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 77–78, 90.

- ^ Dragić 2012, p. 54.

- ^ Janković, Slavko (1956). Kuhačeva zbirka narodnih popijevaka (analizirana): od br. 1801 do br. 2000.

Naša doda moli Boga (Otok, Slavonia, 1881, sken ID: IEF_RKP_N0096_0_155; IEF_RKP_N0096_0_156A) - Ide doda preko sela (Erdevik, Srijem, 1885, sken ID: IEF_RKP_N0096_0_163; IEF_RKP_N0096_0_164A) - Filip i Jakob, Koleda na kišu (Gibarac, Srijem, 1886, sken ID: IEF_RKP_N0096_0_165; IEF_RKP_N0096_0_166A)

- ^ Šenoa, August (1866). "Zagrebulje I (1866.)". Književnost.hr. informativka d.o.o. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

...već se miču niz Okić put naše šljive dvije u zeleno zavite dodole. S ovoga dodolskoga dualizma sjetih se odmah kakvi zecevi u tom grmu idu, i moja me nada ne prevari. Eto ti pred nas dva naša junaka, ne kao dodole, kao bradurina i trbušina, već kao pravi pravcati bogovi – kao Bako i Gambrinus... Naša dva boga, u zeleno zavita, podijeliše društvu svoj blagoslov, te bjehu sa živim usklikom primljeni. No i ova mitologička šala i mrcvarenje božanske poezije po našem generalkvartirmeštru pobudi bogove na osvetu; nad našim glavama zgrnuše se oblaci, i naskoro udari kiša.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 88.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 77, 90.

- ^ Černelić, Milana (1998). "Kroz godinu dana srijemskih običaja vukovarskog kraja" [Annual customs of Srijem in the Vukovar region]. Etnološka tribina (in Croatian). 28 (21): 135.

Bibliography

[edit]- Belaj, Vitomir (2007) [1998]. Hod kroz godinu: Mitska pozadina hrvatskih narodnih običaja i vjerovanja [The walk within a year: the mythic background of the Croatian folk customs and beliefs] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Golden marketing-Tehnička knjiga. ISBN 978-953-212-334-0.

- Burns, Richard (2008). "Rain and Dust". Studia Mythologica Slavica. XI: 217–236. doi:10.3986/sms.v11i0.1696. ISSN 1581-128X.

- Čulinović-Konstantinović, Vesna (1963). "Dodole i prporuše: narodni običaji za prizivanje kiše" [Dodole and prporuše: folk customs for invoking the rain]. Narodna Umjetnost (in Croatian). 2 (1): 73–95.

- Dragić, Marko (2007). "Ladarice, kraljice i dodole u hrvatskoj tradicijskoj kulturi i slavenskom kontekstu" [Ladarice, Queens and Dodole in Croatian Traditionary Culture and Slavic Context]. Hercegovina, godišnjak za kulturno i povijesno naslijeđe (in Croatian). 21: 275–296.

- Gamkrelidze, Ivanov (1995). Indo-European and the Indoeuropeans. Mouton de Gruyter.

- Gieysztor, Aleksander (2006) [1982]. Mitologia Slowian (in Polish) (II ed.). Warszawa: Wydawn. Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego. ISBN 978-83-235-0234-0.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1967). "Ancient Slavic Religion: A Synopsis". To honor Roman Jakobson: essays on the occasion of his seventieth birthday, 11 October 1966 (Vol. I). Mouton. pp. 738–759. doi:10.1515/9783111604763-064. ISBN 978-3-11-122958-4.

- Gjoni, Irena (2012). Marrëdhënie të miteve dhe kulteve të bregdetit të Jonit me areale të tjera mitike (PhD) (in Albanian). Tirana: University of Tirana, Faculty of History and Philology.

- Elsie, Robert (2000). The Christian Saints of Albania. Vol. 13. Balkanistica.

- Elsie, Robert (2001a). A Dictionary of Albanian Religion, Mythology and Folk Culture. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 1-85065-570-7.

- Elsie, Robert (2001b). Albanian Folktales and Legends. Dukagjini Publishing House.

- Evans, David (1974). "Dodona, Dodola, and Daedala". Myth in Indo-European Antiquity. University of California Press. pp. 99–130. ISBN 978-0-520-02378-9.

- Håland, Evy Johanne (2001). "Rituals of Magical Rain-Making in Modern and Ancient Greece: A Comparative Approach". Cosmos. 17: 197–251.

- Halimi, Zanita; Halimi-Statovci, Drita; Xhemaj, Ukë (2011). Rite dhe Aktualiteti [Rites and Contemporariness/Present Time] (PDF). Translated by Lumnije Kadriu. University of Prishtina.

- Jackson, Peter (2002). "Light from Distant Asterisks. Towards a Description of the Indo-European Religious Heritage". Numen. 49 (1): 61–102. doi:10.1163/15685270252772777. ISSN 0029-5973. JSTOR 3270472.

- Jakobson, Roman (1955). "While Reading Vasmer's Dictionary". Word. 11 (4): 611–617. doi:10.1080/00437956.1955.11659581.

- Jakobson, Roman (1985). Selected Writings VII: Contributions to Comparative Mythology. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-010617-6.

- Ḱulavkova, Katica (2020). "A Poetic Ritual Invoking Rain and Well-Being: Richard Berengarten's In a Time of Drought". Anthropology of East Europe Review. 37 (1): 17–26.

- Kulišić, Špiro (1979). Alojz Benac (ed.). Stara slovenska religija u svjetlu novijih istraživanja – posebno balkanoloških (in Serbo-Croatian). Vol. Djela LVI, CBI knjiga 3. Sarajevo: Centre for Balkan Studies, ANUBIH.

- Lajoye, Patrice (2015). Perun, dieu slave de l'orage: Archéologie, histoire, folklore (in French). Lingva. ISBN 979-10-94441-25-1.

- Łuczyński, Michal (2020). Bogowie dawnych Słowian: Studium onomastyczne (in Polish). Kielce: Kieleckie Towarzystwo Naukowe. ISBN 978-83-60777-83-1.

- Ministria e Mjedisit dhe Planifikimit Hapësinor (2014). Parku Kombëtar "Sharri" – Plani Hapësinor. Kosovo Environmental Protection Agency, Institute for Spatial Planning.

- Muraj, Aleksandra (1987). "Iz istraživanja Žumberka (preperuše, preslice, tara)" [From Research on Žumberak (preperuše, spindles, tara)]. Narodna Umjetnost (in Croatian). 24 (1): 157–175.

- Nodilo, Natko (1981) [1884]. Stara Vjera Srba i Hrvata [Old Faith of Serbs and Croats] (in Croatian). Split: Logos.

- Norris, Harry Thirlwall (1993). Islam in the Balkans: Religion and Society Between Europe and the Arab World. Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press. p. 211. ISBN 9780872499775. OCLC 28067651.

- Predojević, Željko (2019). "O pučkim postupcima i vjerovanjima za prizivanje kiše iz južne Baranje u kontekstu dvovjerja" [On folk practices and beliefs for invoking rain from southern Baranja in the context of dual belif]. In István Blazsetin (ed.). XIV. međunarodni kroatistički znanstveni skup (in Croatian). Pečuh: Znanstveni zavod Hrvata u Mađarskoj. pp. 581–593. ISBN 978-963-89731-5-3.

- Puchner, Walter (2009). Studien zur Volkskunde Südosteuropas und des mediterranen Raums (in German). Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag. hdl:20.500.12657/34402. ISBN 978-3-205-78369-5.

- Puhvel, Jaan (1987). Comparative Mythology. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-3938-2.

- Qafleshi, Muharrem (2011). Opoja dhe Gora ndër shekuj [Opoja and Gora During Centuries]. Albanological Institute of Pristina. ISBN 978-9951-596-51-0.

- Sela, Jonida (2017). "Values and Traditions in Ritual Dances of All-Year Celebrations in Korça Region, Albania". International Conference "Education and Cultural Heritage". Vol. 1. Association of Heritage and Education. pp. 62–71.

- Tirta, Mark (2004). Petrit Bezhani (ed.). Mitologjia ndër shqiptarë (in Albanian). Tirana: Mësonjëtorja. ISBN 99927-938-9-9.

- Urbańczyk, Stanisław (1991). Dawni Słowianie: wiara i kult [Old Slavs: faith and cult] (in Polish). Kraków: Ossolineum, Polska Akademia Nauk, Komitet Słowianoznawstwa. ISBN 978-83-04-03825-7.

- Wachtel, Andrew Baruch (2008). The Balkans in World History. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-988273-1.

- West, M. L. (2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928075-9.

- Zebec, Tvrtko (2005). Krčki tanci: plesno-etnološka studija [Tanac dances on the island of Krk: dance ethnology study] (in Croatian). Zagreb, Rijeka: Institut za etnologiju i folkloristiku, Adamić. ISBN 953-219-223-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Bellosics, Bálint. "Dodola (Adatok az esőcsináláshoz)" [Dodola, Beiträge zum Regenmachen]. In: Ethnographia 6 (1895): 418–422. (In Hungarian)

- Beza, Marcu (1928). "The Paparude and Kalojan". Paganism in Roumanian Folklore. London: J.M.Dent & Sons LTD. pp. 27–36. ISBN 978-3-8460-4695-1.

- Boghici, Constantina. "Archaic Elements in the Romanian Spring-Summer Traditions. Landmarks for Dâmboviţa County". In: Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov, Series VIII: Performing Arts 2 (2013): 17–18. https://ceeol.azurewebsites.net/search/article-detail?id=258246

- Cook, Arthur Bernard (1940). "Zeus and the Rain: Rain-magic in modern Greece". Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion: God of the Dark Sky (earthquakes, clouds, wind, dew, rain, meteorites). Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press. pp. 284–290. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511696640. ISBN 978-0-511-69664-0.

- Dömötör, Tekla; Eperjessy, Ernő. "Dodola and Other Slavonic Folk-Customs in County Baranya (Hungary)". In: Acta Ethnographica, 16 (1967): 399–408.

- Dragnea, Mihai (2012). "Paparuda" [Paparuda]. Anuarul Muzeului Etnografic al Transilvaniei (in Romanian) (6). MUZEUL ETNOGRAFIC AL TRANSILVANIEI: 73–81.

- Ganeva, Bozhanka (2003). "Песента в обреда Пеперуда" [The Song in the Peperuda Ritual]. Български фолклор (in Bulgarian). XXIX (1). Институт за етнология и фолклористика с Етнографски музей при БАН: 40–49.

- Janković, Danica S., and Ljubica S. Janković. "Serbian Folk Dance Tradition in Prizren". In: Ethnomusicology 6, no. 2 (1962): 117. https://doi.org/10.2307/924671.

- Kalev, Rusko (1986). "Вариантн на обредите Пеперуда и Герман" [Variants of the Rites Peperuda and German]. Български фолклор (in Bulgarian). XII (3). Институт за етнология и фолклористика с Етнографски музей при БАН: 47–58.

- Kruszec, Agata (2008). "Słownictwo związane z wywoływaniem deszczu w dialektach sztokawskich" [Vocabulary related to rain calling in Shtokavian dialects]. Studia z Filologii Polskiej i Słowiańskiej (in Polish) (43). Instytut Slawistyki Polskiej Akademii Nauk: 141–148.

- Мандич, Мария. ""Жизнь" ритуала после "угасания": Пример додолы из села Сигетчеп в Венгрии" [The 'life' of an extinguished ritual: The case of the rain ritual dodola from Szigetcsép in Hungary]. In: "Славяноведение" 6 (2019): 15–29. DOI: 10.31857/S0869544X0006755-3 (In Russian)

- Marushiakova, E.; Popov, V. (2016). "Roma Culture: Problems and Challenges". In Marushiakova, E.; Popov, V. (eds.). Roma Culture: Myths and Realities. München: Lincom Academic Publishers. p. 48.

- Mikov, Lyubomir (1985). "Женска антропоморфна пластика в два обреда за дъжд от Ямболски окръг" [Female Anthropomorphic Figures in Two Rain-Making Ceremonies from the District of Yambol]. Български фолклор (in Bulgarian). XI (4). Институт за етнология и фолклористика с Етнографски музей при БАН: 19–27.

- Puchner, Walter. "Liedtextstudien Zur Balkanischen Regenlitanei: Mit Spezieller Berücksichtigung Der Bulgarischen Und Griechischen Varianten". In: Jahrbuch Für Volksliedforschung 29 (1984): 100–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/849291.

- Schneeweis, Edmund (2019) [1961]. Serbokroatische Volkskunde: Volksglaube und Volksbrauch (in German). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 161–163. ISBN 978-3-11-133764-7.

- MacDermott, Mercia (2003). Explore Green Men. Heart of Albion Press. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-1-872883-66-3.

- Croatian Encyclopaedia (2021), Dodole

External links

[edit]- Dodole ritual on TV in Macedonia on YouTube

- Reconstruction of Dodole ritual in Bulgaria on YouTube at Etar Architectural-Ethnographic Complex

- "Dodole" song by Croatian ethno-folk rock band Kries on YouTube

- Pirpirouna/Pirpiruna/Perperouna – Rainmaking ritual song, and its lyrics, recorded 2016 by Thede Kahl and Andreea Pascaru in Turkey

- Dodola/Pirpiruna – Rainmaking ritual song, description of the custom and its lyrics, recorded 2020 in Northeast Greece by Sotirios Rousiakis