Pennsylvania Dutch

Pennsylvanisch Deitsche (Pennsylvania German) | |

|---|---|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Pennsylvania Ohio, Indiana, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, West Virginia, California, Ontario | |

| Languages | |

| Pennsylvania Dutch Pennsylvania Dutch English | |

| Religion | |

| Lutheran, Reformed, German Reformed, Catholic, Moravian, Church of the Brethren, Mennonite, Amish, Schwenkfelder, River Brethren, Yorker Brethren, Judaism, Pow-wow, Jehovah's Witnesses | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Palatines, Ohio Rhinelanders, Fancy Dutch, Missouri Rhinelanders, Maryland Palatines |

The Pennsylvania Dutch (Pennsylvania German: Pennsylvanisch Deitsche),[1][2][3] also referred to as Pennsylvania Germans, are an ethnic group in Pennsylvania (U.S.), Ontario (Canada) and other regions of the United States and Canada, most predominantly in the US Mid-Atlantic region.[4][5] They largely originate from the Palatinate region of Germany, and settled in Pennsylvania during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. While most were from the Palatinate region of Germany, a lesser number were from other German-speaking areas of Germany and Europe, including Baden-Württemberg, Hesse, Saxony, and Rhineland in Germany, Switzerland, and the Alsace–Lorraine region of France.[6][7][8]

The Pennsylvania Dutch are either monolingual English speakers or bilingual speakers of both English and the Pennsylvania Dutch language, which is also commonly referred to as Pennsylvania German.[9] Linguistically it consists of a mix of German dialects which have been significantly influenced by English, primarily in terms of vocabulary. Based on dialect features, Pennsylvania Dutch can be classified as a variety of Rhine Franconian, with the Palatine German dialects being most closely related.[10][11]

Geographically, Pennsylvania Dutch are largely found in the Pennsylvania Dutch Country and Ohio Amish Country. The main division among Pennsylvania Dutch is that between sectarians (those belonging to the Old Order Mennonite, Amish or related groups) and nonsectarians, sometimes colloquially referred to as ″Church Dutch″ or ″Fancy Dutch″.[12]

Notable Americans of Pennsylvania Dutch descent include Henry J. Heinz, founder of the Heinz food conglomerate, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, and the family of businessman Elon Musk.[13]

Etymology

Differing explanations exist on why the Pennsylvania Dutch are referred to as Dutch, which typically refers to the inhabitants of the Netherlands or the Dutch language.

Several authors and etymological publications consider the word Dutch in Pennsylvania Dutch, which in medieval times could also be used to refer to speakers of various German dialects, to be an archaism specific to 19th-century American English, particularly in its colloquial form.[14] This is corroborated with evidence, such as one of the oldest German newspapers in Pennsylvania being the High-Dutch Pennsylvania Journal in 1743.[15][16]

An alternative interpretation commonly found among laypeople and scholars alike is that the Dutch in Pennsylvania Dutch is an anglicization or "corruption" (folk-etymological re-interpretation) of the Pennsylvania German autonym deitsch, which in the Pennsylvania German language refers to the Pennsylvania Dutch or Germans in general.[17][18] However, some authors have described[further explanation needed] this hypothesis[clarification needed] as a misconception.[14][19]

The migration of the Pennsylvania Dutch to the United States predates the emergence of a distinct German national identity, which did not form until the late 18th century.[20] The formation of the German Empire in 1871 resulted in a semantic shift, in which deutsch was no longer principally a linguistic and cultural term, but was increasingly used to describe all things related to Germany and its inhabitants. This development did not go unnoticed among the Pennsylvania Dutch who, in the 19th and early 20th century, referred to themselves as Deitsche, while calling newer German immigrants Deitschlenner lit. 'Germany-ans'.[21]

Geographic distribution

The Pennsylvania Dutch live primarily in the Delaware Valley and in the Pennsylvania Dutch Country, a large area that includes South Central Pennsylvania, in the area stretching in an arc from Bethlehem and Allentown in the Lehigh Valley westward through Reading, Lebanon, and Lancaster to York and Chambersburg. Smaller enclaves include Pennsylvania Dutch-speaking areas in New York, Delaware, Maryland, Ohio, West Virginia, North Carolina, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, Virginia, and the Canadian province of Ontario.[22][23][24]

History

Immigration to America

The Pennsylvania Dutch, primarily German-speaking immigrants from Germany (particularly the Palatinate region), Switzerland, and Alsace, moved to the USA seeking better opportunities and a safer, more tolerant environment. Many, including Amish and Mennonites, faced religious persecution in Europe. Pennsylvania, established by William Penn as a haven for religious minorities, promised the religious freedom they sought. Economic hardship, marked by war, famine, and limited land access in 17th and 18th century Germany, pushed many to seek a better life in the New World, which offered abundant land and resources.

Europe's, and especially Germany's, political instability, with frequent wars like the devastating Thirty Years' War, contrasted with the relatively stable environment of the American colonies. The availability of fertile land was a significant draw for the immigrants, who were mainly farmers and craftsmen, for whom the chance to own and cultivate their own farms was highly appealing. Positive reports from early settlers as well as active recruitment by William Penn encouraged friends and family to join them, fostering tightly knit communities.

About three fourths of all Germans in Pennsylvania were subject to several years of indentured servitude contracts. These indentured servants, known as redemptioners, were made to work on plantations or perform other work to pay off the costs of the sponsor or shipping company which had advanced the cost of their transatlantic voyage.[25] In 1764, the German Society of Pennsylvania was founded to protect the German redemptioners.[26][27]

The bulk of German migration to the American colonies began in 1683 but concentrated on the first half of the 18th century.[28] Overall, the historian Marianne Wokeck estimates that just under 81,000 German-speakers entered the port of Philadelphia between 1683 and 1775, with two thirds of the immigrants arriving before 1755 of whom the majority (ca. 35,000) arrived in the five-year period between 1749 and 1754.[29] In 1790, ethnic Germans comprised 38% of the population of Pennsylvania, or approximately 165,000 people. Of these, over half resided in the counties of Berks, Lancaster, Northampton and York.[9]

Anglo-Americans held much anti-Palatine sentiment in the Pennsylvania Colony. Below is a quotation of Benjamin Franklin's complaints about the Palatine refugees in his work Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind (1751):

Why should the Palatine boors be suffered to swarm into our settlements, and by herding together establish their language and manners to the exclusion of ours? Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a colony of aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of us Anglifying them, and will never adopt our language or customs, any more than they can acquire our complexion.

The Germans who immigrated to the United States saw themselves as related though distinct from later (post-1830) waves of German-speaking immigrants. The Pennsylvania Dutch referred to themselves as Deitsche and would refer to Germans who arrived after the period of almost non-existent emigration between 1760 and 1830 from the German lands as Deitschlenner, literally "Germany-ers", compare German: Deutschländer.[30][31]

Pennsylvania Dutch during the American Revolutionary War

The Pennsylvania Dutch composed nearly half of the population of the Province of Pennsylvania. The Fancy Dutch population generally supported the Patriot cause in the American Revolution; the nonviolent Plain Dutch minority did not fight in the war.[32] Heinrich Miller of the Holy Roman Principality of Waldeck (1702–1782), was a journalist and printer based in Philadelphia, and published an early German translation of the Declaration of Independence (1776) in his newspaper Philadelphische Staatsbote.[33] Miller, having Swiss ancestry, often wrote about Swiss history and myth, such as the William Tell legend, to provide a context for patriot support in the conflict with Britain.[34]

Frederick Muhlenberg (1750–1801), a Lutheran pastor, became a major patriot and politician, rising to be elected as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives.[35]

The Pennsylvania Dutch contribution to the war effort was notable:

In the marked influence for right and freedom of these early Hollanders and Palatines, in their brave defense of home, did such valiant service in promoting a love of real freedom to the preserving and hence making of our country.

In the town halls in Dutch cities liberty bells were hung, and from the "Liberty Bell" placed in Philadelphia by Pennsylvania Dutchmen, on July 4th 1776, freedom was proclaimed "throughout all the land and to all the inhabitants thereof." These Palatine Dutchmen gave us some of our bravest men in the war of the American Revolution, notably Nicholas Herkimer.[36]

Many Hessian prisoners, German mercenaries fighting for the British, were held in camps at the interior city of Lancaster, home to a large German community known as the Pennsylvania Dutch. Hessian prisoners were subsequently treated well, with some volunteering for extra work assignments, helping to replace local men serving in the Continental Army. Due to shared German heritage and abundance of land, many Hessian soldiers stayed and settled in the Pennsylvania Dutch Country after the war's end.[37]

Pennsylvania Dutch Provost Corps

Pennsylvania Dutch were recruited for the American Provost corps under Captain Bartholomew von Heer,[38][Note 1] a Prussian who had served in a similar unit in Europe[39] before immigrating to Reading, Pennsylvania, prior to the war.

During the Revolutionary War the Marechaussee Corps were utilized in a variety of ways, including intelligence gathering, route security, enemy prisoner of war operations, and even combat during the Battle of Springfield.[40] The Marechausee also provided security for Washington's headquarters during the Battle of Yorktown, acted as his security detail, and was one of the last units deactivated after the Revolutionary War.[38] The Marechaussee Corps was often not well received by the Continental Army, due in part to their defined duties but also due to the fact that some members of the corps spoke little or no English.[39] Six of the provosts had even been Hessian prisoners of war prior to their recruitment.[39] Because the provost corps completed many of the same functions as the modern U.S. Military Police Corps, it is considered a predecessor of the current United States Military Police Regiment.[40]

Pennsylvania Dutch during the Civil War

Nearly all of the regiments from Pennsylvania that fought in the American Civil War had German-speaking or Pennsylvania Dutch-speaking members on their rosters, the majority of whom were Fancy Dutch.[41]

Some regiments like the 153rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were entirely composed of Pennsylvania Dutch soldiers.[42] The 47th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment also had a high percentage of German immigrants and Pennsylvania-born men of German heritage on its rosters; the regiment's K Company was formed with the intent of it being an "all-German company."[43][44][45]

Pennsylvania Dutch companies sometimes mixed with English-speaking companies. (The Pennsylvania Dutch had the habit of labeling anyone who did not speak Pennsylvania Dutch "English.") Many of the Pennsylvania Dutch soldiers who fought in the Civil War were recruited and trained at Camp Curtin, Pennsylvania.[42]

Pennsylvania Dutch regiments composed a large portion of the Federal Forces who fought in the Battle of Gettysburg at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the bloodiest battle of the Civil War.[46]

Decline of the Pennsylvania Dutch

Immediately after the Civil War, the federal government took steps to replace Pennsylvania German schools with English-only schools. The Pennsylvania Dutch fought to retain German as an official language in Pennsylvania to little success.[47][better source needed]

Literary German disappeared from Pennsylvania Dutch life little by little, starting with schools, and then to churches and newspapers. Pennsylvania Dutch became mainly a spoken language, and as education came to only be provided in English, many Pennsylvania Dutch became bilingual.[47][better source needed]

Anti-German sentiment and Americanization

The next blow to Pennsylvania Dutch came during World War I and World War II. Prior to the wars, Pennsylvania Dutch was an urban language spoken openly in the streets of towns such as Allentown, Reading, Lancaster and York; afterwards, it became relegated only to rural areas.[47][better source needed]

There was rampant social & employment discrimination for anyone suspected of being German. Meritt G. Yorgey, a Pennsylvania Dutch descendant who grew up during the height of anti-German sentiment, remembers the instructions of his father: "Don't ever call yourself "Dutch" or "Pennsylvania German." You're just American."[47][better source needed]

Many Pennsylvania Dutch have chosen to assimilate into Anglo-American culture, except for a significant number of Amish and Mennonite plain people who chose to remain insular, which has added to the modern misconception that "Pennsylvania Dutch" is synonymous with "Amish."[47]

Pennsylvania Dutch during World War I

Palatine Dutch of New York in the 27th Infantry Division broke through the Hindenburg Line in 1917.[48]

Interwar period

Before World War II, the Nazi Party sought to gain the loyalty of the German-American community, and established pro-Nazi German-American Bunden, emphasizing German-American immigrant ties to the "Fatherland". The Nazi propaganda effort failed in the Pennsylvania Dutch community, as the Pennsylvania Dutch felt no sense of loyalty to Germany.[49]

Pennsylvania Dutch during World War II

During World War II, a platoon of Pennsylvania Dutch soldiers on patrol in Germany was once spared from being machine-gunned by Nazi soldiers who listened to them approaching. The Germans heard them speaking Pennsylvania Dutch amongst each other and assumed that they were natives of the Palatinate.[50]

Canadian Pennsylvania Dutch

An early group, mainly from the Roxborough-Germantown area of Pennsylvania, emigrated to then colonial Nova Scotia in 1766 and founded the Township of Monckton, site of present-day Moncton, New Brunswick. The extensive Steeves clan descends from this group.[51]

After the American Revolution, John Graves Simcoe, lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, invited Americans, including Mennonites and German Baptist Brethren, to settle in British North American territory and offered tracts of land to immigrant groups.[52][53] This resulted in communities of Pennsylvania Dutch speakers emigrating to Canada, many to the area called the German Company Tract, a subset of land within the Haldimand Tract, in the Township of Waterloo, which later became Waterloo County, Ontario.[54][55] Some still live in the area around Markham, Ontario,[56][57] and particularly in the northern areas of the current Waterloo Region. Some members of the two communities formed the Markham-Waterloo Mennonite Conference. Today, the Pennsylvania Dutch language is mostly spoken by Old Order Mennonites.[58][54][59]

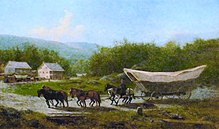

From 1800 to the 1830s, some Mennonites in Upstate New York and Pennsylvania moved north to Canada, primarily to the area that would become Cambridge, Kitchener/Waterloo and St. Jacobs/Elmira in Waterloo County, Ontario, plus the Listowel area adjacent to the northwest. Settlement started in 1800 by Joseph Schoerg and Samuel Betzner Jr. (brothers-in-law), Mennonites, from Franklin County, Pennsylvania. Other settlers followed mostly from Pennsylvania typically by Conestoga wagons. Many of the pioneers arriving from Pennsylvania after November 1803 bought land in a sixty thousand-acre section established by a group of Mennonites from Lancaster County Pennsylvania, called the German Company Lands.[58][60]

Fewer of the Pennsylvania Dutch settled in what would later become the Greater Toronto Area in areas that would later be the towns of Altona, Ontario, Pickering, Ontario, and especially Markham Village, Ontario, and Stouffville, Ontario.[61] Peter Reesor and brother-in-law Abraham Stouffer were higher profile settlers in Markham and Stouffville.

William Berczy, a German entrepreneur and artist, had settled in upstate New York and in May 1794, he was able to obtain sixty-four acres in Markham Township, near the current city of Toronto. Berczy arrived with approximately one hundred and ninety German families from Pennsylvania and settled here. Others later moved to other locations in the general area, including a hamlet they founded, German Mills, Ontario, named for its grist mill; that community is now called Thornhill, Ontario, in the township that is now part of York Region.[56][57]

Canadian Black Mennonites

In Canada, an 1851 census shows many Black people and Mennonites lived near each other in a number of places and exchanged labor; the Dutch would also hire Black laborers. There were also accounts of Black families providing childcare assistance for their Dutch neighbors. These Pennsylvania Dutch were usually Plain Dutch Mennonites or Fancy Dutch Lutherans.[62] The Black-Mennonite relationship in Canada soon evolved to the level of church membership.[62]

Society

Pennsylvania Dutch society can be divided into two main groups: the sectarian "Plain Dutch" and the nonsectarian "Church Dutch" also known as "Fancy Dutch".[63][64] These classifications highlight differences in religious practices, lifestyle, and degrees of assimilation into broader American society.

The Plain Dutch consist of Anabaptist sects, including the Amish, Mennonites, and Brethren. They are known for their conservative, simple lifestyle, characterized by plain dress and limited use of modern technology. These communities typically reside in rural areas, maintaining traditional farming practices and close-knit communal living. Pennsylvania Dutch (a dialect of German) is widely spoken among them, both in daily life and religious settings. The Plain Dutch adhere strictly to their religious and community norms, emphasizing a strong cultural and religious identity with minimal integration into mainstream American culture.

The Church Dutch, in contrast, belong to more mainstream Protestant denominations such as Lutheran, Reformed, United Church of Christ, and some Methodist and Baptist congregations. This group is more integrated into broader American society and is more likely to adopt modern conveniences and technologies. While they may still preserve some Pennsylvania Dutch traditions and language, English is predominantly used in daily life and religious practices. The Church Dutch exhibit a higher degree of assimilation into American culture, while still retaining elements of their Pennsylvania Dutch heritage.

The primary differences between these groups lie in their religious practices, lifestyle, language use, and cultural integration. The Plain Dutch are more conservative and focused on maintaining their distinct cultural identity, whereas the Church Dutch are more assimilated and open to modern influences. In time the Fancy Dutch came to control much of the best agricultural lands, ran many newspapers and maintained their German-inspired architecture when founding new towns in Pennsylvania.[42]

There is little evidence specifically of Black Pennsylvania Dutch speakers during the early 19th century; following the Civil War, some Black Southerners who had moved to Pennsylvania developed close ties with the Pennsylvania Dutch community, adopting the language and assimilating into the culture. An 1892 article in The New York Sun noted a community of "Pennsylvania German Negroes" in Lebanon County for whom German was their first language.[65]

Today Pennsylvania Dutch culture is still prevalent in some parts of Pennsylvania. The Pennsylvania Dutch speak English, with some being bilingual in English and Pennsylvania Dutch. They share cultural similarities with the Mennonites in the same area. Pennsylvania Dutch English retains some German grammar and literally translated vocabulary, some phrases include "outen or out'n the lights" (German: die Lichter loeschen) meaning "turn off the lights", "it's gonna make wet" (German: es wird nass) meaning "it's going to rain", and "it's all" (German: es ist alle) meaning "it's all gone". They also sometimes leave out the verb in phrases turning "the trash needs to go out" in to "the trash needs out" (German: der Abfall muss raus), in alignment with German grammar.

Cuisine

The Pennsylvania Dutch have some foods that are uncommon outside of places where they live. Some of these include shoo-fly pie, funnel cake, pepper cabbage, filling and jello salads such as strawberry pretzel salad.

Religion

The Pennsylvania Dutch maintain numerous religious affiliations; the greatest number are Lutheran or German Reformed with a lesser number of Anabaptists, including Mennonites, Amish, and Brethren. The Anabaptist groups espoused a simple lifestyle, and their adherents were known as Plain Dutch; this contrasts with the Fancy Dutch, mostly of the Lutheran, or Evangelical and Reformed churches, who tended to assimilate more easily into the American mainstream. By the late 1700s, other denominations were also represented in smaller numbers.[66]

Among immigrants from the 1600s and 1700s, those known as the Pennsylvania Dutch included Mennonites, Swiss Brethren (also called Mennonites by the locals) and Amish but also Anabaptist-Pietists such as German Baptist Brethren and those who belonged to German Lutheran or German Reformed Church congregations.[67][68] Other settlers of that era were of the Moravian Church while a few were Seventh Day Baptists.[69][70] Calvinist Palatines and several other denominations were also represented to a lesser extent.[71][72]

Over sixty percent of the immigrants who arrived in Pennsylvania from Germany or Switzerland in the 1700s and 1800s were Lutherans and they maintained good relations with those of the German Reformed Church.[73] The two groups founded Franklin College (now Franklin & Marshall College) in 1787.

According to Elizabeth Pardoe, by 1748, the future of the German culture in Pennsylvania was in doubt, and most of the attention focused on German language schools. Lutheran schools in Germantown and Philadelphia thrived, but most outlying congregations had difficulty recruiting students. Furthermore, Lutherans were challenged by Moravians who actively recruited Lutherans to their schools. In the 1750s, Benjamin Franklin led a drive for free charity schools for German students, with the proviso that the schools would minimize Germanness. The leading Lutheran school in Philadelphia school had internal political problems in the 1760s, but Pastor Henry Melchior Muhlenberg resolved them. The arrival of John Christopher Kunze from Germany in 1770 gave impetus to the Halle model in America. Kunze began training clergy and teachers in the Halle system. Reverend Heinrich Christian Helmuth arrived in 1779 and called for preaching only in German, while seeking government subsidies. A major issue was the long-term fate of German culture in Pennsylvania, with most solutions focused on schools. Helmuth saw schools as central to the future of the ethnic community. However most Lutheran clergy believed in assimilation and rejected Helmuth's call to drop English instruction. Kunze's seminary failed, but the first German college in the United States was founded in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 1787 as Franklin College; it was later renamed Franklin and Marshall College.[74][75][76] The Moravians settled Bethlehem and nearby areas and established schools for Native Americans.[71]

In Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Dutch Christians and Pennsylvania Dutch Jews have often maintained a special relationship due to their common German language and cultural heritage. Because both Yiddish and the Pennsylvania Dutch language are High German languages, there are strong similarities between the two languages and a limited degree of mutual intelligibility.[77] Historically, Pennsylvania Dutch Christians and Pennsylvania Dutch Jews often had overlapping bonds in German-American business and community life. Due to this historical bond there are several mixed-faith cemeteries in Lehigh County, including Allentown's Fairview Cemetery, where German-Americans of both the Jewish and Protestant faiths are buried.[78]

Language

Although speakers of Pennsylvania Dutch can be found among both sectarians and nonsectarians, most speakers belong to the Old Order Amish and Old Order Mennonites. Nearly all Amish and Mennonites are naturally bilingual, speaking both Pennsylvania Dutch and English natively.[9] The Pennsylvania Dutch language is based on German dialects which have been significantly influenced by English, primarily in terms of vocabulary. Based on dialect features, Pennsylvania Dutch can be classified as a variety of Rhine Franconian, with the Palatine German dialects being most closely related.[10][11] The language is both commonly referred to as Pennsylvania Dutch and Pennsylvania German, with the latter being more common in scholarly publications.[9]

The primary use of Pennsylvania Dutch, both historically and today, has focussed on spoken communication. Although there is a relatively large collection of written texts in the language dating back to the mid-nineteenth century (such as newspaper columns, short stories, poems, plays, and dialogues) their production and reception have been limited to a minority of speakers. The significance of English among today's sectarians extends far beyond its use for communication with outsiders for business and other purposes as English is the primary language for active literacy. While Amish and Mennonite sectarians can read the Bible, prayer books, and hymnals in German, most other reading materials are in English.[9] Research has show that nonsectarian speakers of Pennsylvania Dutch have a more pronounced Pennsylvania Dutch accent when speaking English compared to sectarian speakers such as the Old Order Amish or Old Order Mennonites.[79]

In the 20th century, the linguists Albert F. Buffington and Preston A. Barba developed a system for writing Pennsylvania Dutch that was largely based on contemporary German orthography, however this is not in common use. No prescribed norms for writing Pennsylvania Dutch exist and in practice most speakers orientate themselves on both German and English spelling systems.[9]

| Pennsylvania German | Standard German | English |

|---|---|---|

| Saagt mer mol, wie soll mer schpelle. | Sag mir mal, wie sollen wir buchstabieren? | So tell me, how should you spell? |

| Sel macht immer bissel Schtreit; | Das macht immer ein bisschen Streit; | That always makes a bit of an argument. |

| was ner nau net hawwe welle, | was wir nun nicht haben wollen, | What you don't want to deal with, |

| schiebt mer graad mol uf die Seit. | schieben wir gerade mal auf die Seite. | you just push off to the side. |

| Saagt, wie soll mer buchschtawiere, | Sag mir mal, wie sollen wir buchstabieren, | Tell me, how should you orthographize, |

| in de scheene deitsche Schproch! | in der schönen deutschen Sprache! | in beautiful Pennsylvania Dutch language! |

| Brauch mer noh ke Zeit verliere, | Brauchen wir nur keine Zeit zu verlieren, | No point in wasting any time, |

| macht mer's ewwe yuscht so nooch. | machen wir es eben just so nach. | you just follow whatever model you please. |

Due to anti-German sentiment between World War I and World War II, the use of the Pennsylvania Dutch language declined, except among the more insular and tradition-bound Plain people, such as the Old Order Amish and Old Order Mennonites. Many German cultural practices continue in Pennsylvania in the present-day, and German remains the largest ancestry claimed by Pennsylvanians, according to the 2008 census.[80][47]

Notable people

- Jacob Albright (1759–1808), founder of the Evangelical Association

- Anne F. Beiler (1949–present), founder of Auntie Anne's Pretzels

- John Birmelin (1873–1950), poet, playwright

- Solomon DeLong (1849–1925), writer, journalist

- George Ege (1748–1829), Representative for Pennsylvania

- Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969), 34th President of the United States

- H. L. Fischer (1822–1909), writer, translator

- Heinrich Funck (c. 1697 – 1730), miller, author, Mennonite bishop

- John Fries (1750–1818), auctioneer, organizer of Fries's Rebellion

- Betty Groff (1935–2015), celebrity chef, cookbook author

- Michael Hillegas (1729–1804), first Treasurer of the United States

- Hedda Hopper (1885–1966), actress, gossip columnist

- Ralph Kiner (1922–2014), Hall of Fame baseball player and Pittsburgh Pirates and New York Mets legend.

- William Kohl (1820–1892), sea captain, shipowner, shipbuilder, businessman

- James H. Maurer (1864–1944), Labor leader, three-term Pennsylvania House of Representatives member, and two-time Vice Presidential nominee

- Stephen Miller (1816–1881), 4th Governor of Minnesota

- Bodo Otto (1711–1787), physician in the Continental Army

- Harry Hess Reichard (1878–1956), writer, scholar

- Joseph Ritner (1780–1869), 8th Governor of Pennsylvania

- Victor Schertzinger (1888–1941), composer, film director, producer, screenwriter

- Evelyn Ay Sempier (1933–2008), Miss America 1954

- Francis R. Shunk (1788–1848), 10th Governor of Pennsylvania

- Simon Snyder (1759–1813), 3rd Governor of Pennsylvania

- Clement Studebaker (1831–1901), co-founder of Studebaker Corporation

- Clement Studebaker Jr. (1871–1932), businessman, son of Clement Studebaker Sr.

- John Studebaker (1833–1917), co-founder of Studebaker Corporation

- Conrad Weiser (1696–1760), colonial diplomat between Pennsylvania and Native American nations.

See also

- List of Amish and their descendants

- German American

- Preston Barba, historian and linguist

- Helen Reimensnyder Martin, author

- Anna Balmer Myers, author

- Michael Werner (publisher)

- John Schmid, singer

- Fraktur (Pennsylvania German folk art)

- Hex sign

- Hiwwe wie Driwwe newspaper

- Kurrent handwriting

- Schwenkfeldian (church)

- Old German Baptist Brethren (church)

- Pow-wow

Notes

- ^ "It is interesting to note that nearly all men recruited into the Provost Corps were Pennsylvania German." -David L. Valuska Archived November 27, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

References

- ^ Oscar Kuhns (2009). The German and Swiss Settlements of Colonial Pennsylvania A Study of the So-called Pennsylvania Dutch. Abigdon Press. p. 254.

- ^ William J. Frawley (2003). International Encyclopedia of Linguistics 2003. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 92.

- ^ Joshua R. Brown; Simon J. Bronner (2017). Pennsylvania Germans An Interpretive Encyclopedia · Volume 63. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 3.

- ^ University of Michigan (1956). Americas (English Ed.) Volume 8. Organization of American States. p. 21.

- ^ United States. Department of Agriculture (1918). Weekly News Letter to Crop Correspondents. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 5.

- ^ Janne Bondi Johannessen; Joseph C. Salmons (2015). Germanic Heritage Languages in North America: Acquisition, attrition and change. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 11.

- ^ Fred Lewis Pattee (2015). The House of the Black Ring: A Romance of the Seven Mountains. Penn State Press. p. 218.

- ^ Norm Cohen (2005). Folk Music: A Regional Exploration. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 105.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mark L. Louden: Pennsylvania Dutch: The Story of an American Language. JHU Press, 2006, pp. 1-2; pp. 60-66; pp. 342-343.

- ^ a b Michael T. Putnam: Studies on German-Language Islands, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2011, p. 375

- ^ a b Joachim Scharloth, Nils Langer, Stephan Elspaß & Wim Vandenbussche: Germanic Language Histories 'from Below' (1700-2000), De Gruyter, 2011, p. 166.

- ^ Steven M. Nolt (March 2008). Foreigners in their own land: Pennsylvania Germans in the early republic. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780271034447.

- ^ Elliott, Hannah (March 26, 2012). "At Home With Elon Musk: The (Soon-to-Be) Bachelor Billionaire". Forbes. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

- ^ a b Mark L. Louden: Pennsylvania Dutch: The Story of an American Language. JHU Press, 2006, p.2

- ^ Watson, John Fanning (1881), Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania, J.M. Stoddart

- ^ United States. Census Office (1883), Census Reports Tenth Census: The newspaper and periodical press, U.S. Government Printing Office, pp. 126, 127

- ^ Nicoline van der Sijs:Cookies, Coleslaw, and Stoops: The Influence of Dutch on the North American Languages. Amsterdam University Press, 2009, page 15.

- ^ Sally McMurry: Architecture and Landscape of the Pennsylvania Germans, 1720-1920. University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated, 2011, page 2.

- ^ Hostetler, John A. (1993), Amish Society, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, p. 241

- ^ Hans Kohn (1951): The Eve of German Nationalism (1789–1812). In: Journal of the History of Ideas. Bd. 12, Nr. 2, S. 256–284, hier S. 257 (JSTOR 2707517).

- ^ Mark L. Louden: Pennsylvania Dutch: The Story of an American Language. JHU Press, 2006, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Steven M. Nolt (March 2008). Foreigners in their own land: Pennsylvania Germans in the early republic. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780271034447.

- ^ Mark L. Louden (2016). Pennsylvania Dutch: The Story of an American Language. United States of America: JHU Press. p. 404.

- ^ David W. Guth (2017). Bridging the Chesapeake, A 'Fool Idea' That Unified Maryland. Archway Publishing. p. 426.

- ^ Kenneth L. Kusmer (1991). Black Communities and Urban Development in America, 1720-1990: The Colonial and early national period. Gardland Publisher. pp. 63, 228.

- ^ Pennsylvania State University (1978). Germantown Crier, Volumes 30-32. Germantown Historical Society. pp. 12, 13.

- ^ H. Carter (1968). The Past as Prelude: New Orleans, 1718-1968. Pelican Publishing. p. 37.

- ^ Sudie Doggett Wike (2022). German Footprints in America, Four Centuries of Immigration and Cultural Influence. McFarland Incorporated Publishers. p. 155.

- ^ Marianne Sophia Wokeck: Trade in Strangers: The Beginnings of Mass Migration to North America. Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999, pp. 44-47

- ^ Mark L. Louden: Pennsylvania Dutch: The Story of an American Language. JHU Press, 2006, p.3-4

- ^ Frank Trommler; Joseph McVeigh (2016). America and the Germans, Volume 1: An Assessment of a Three-Hundred Year History--Immigration, Language, Ethnicity. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 51.

- ^ John B. Stoudt, "The German Press in Pennsylvania and the American Revolution." Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 59 (1938): 74–90 online[permanent dead link]

- ^ Patrick Erben. "Henrich Miller". immigrantentrepreneurship.org. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ A. G.. Roeber, "Henry Miller's Staatsbote: A Revolutionary Journalist's Use of the Swiss Past", Yearbook of German-American Studies, 1990, Vol. 25, pp 57–76

- ^ "Muhlenberg, Frederick Augustus Conrad" (biography), in "History, Art & Archives." Washington, D.C.: United States House of Representatives, retrieved online December 18, 2022.

- ^ A. T. Smith (1899). Papers Read Before the Herkimer County Historical Society During the Years... Volumes 1-2. Herkimer County Historical Society. Macmillan. pp. 171, 300.

- ^ "Lititz – Keeping History Alive". lancastercountymag.com.

- ^ a b Valuska, David L., Ph.D. (2007). "Von Heer's Provost Corps Marechausee: The Army's Military Police. An All Pennsylvania German Unit". The Continental Line, Inc. Archived from the original on November 27, 2022. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Ruppert, Bob (October 1, 2014). "Bartholomew von Heer and the Marechausse Corps". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ a b "Order of the Marechaussee" (PDF). The Dragoon. 26 (2). Fort Leonard Wood: Military Police Regimental Association: 8. Spring 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ^ Donald B. Kraybill (2003). The Amish and the State. JHU Press. p. 45.

- ^ a b c David L. Valuska, Christian B. Keller (2004). Damn Dutch: Pennsylvania Germans at Gettysburg. United States of America: Stackpole Books. pp. 5, 6, 9, 216.

- ^ History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5; prepared in compliance with acts of the legislature, Vol. I, pp. 1150-1190. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- ^ Snyder, Laurie. "About the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers," in 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment's Story. Pennsylvania: 2014.

- ^ Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: L. G. Schmidt, 1986.

- ^ John G. Sabol Jr. (2007). Gettysburg Unearthed: The Excavation of a Haunted History. United States of America: AuthorHouse. p. 172.

- ^ a b c d e f Merritt George Yorgey (2008). A Pennsylvania Dutch Boy And the Truth About the Pennsylvania Dutch. United States of America: Xlibris US. pp. 17, 18, 19.

- ^ Nelson Greene (1925). History of the Mohawk Valley, Gateway to the West, 1614-1925 Covering the Six Counties of Schenectady, Schoharie, Montgomery, Fulton, Herkimer, and Oneida · Volume 1. United States of America: S. J. Clarke. p. 475.

- ^ Irwin Richman (2004). The Pennsylvania Dutch Country. United States of America: Arcadia. p. 22.

- ^ Robert Hendrickson (2000). The Facts on File Dictionary of American Regionalisms. United States of America: Infobase Publishing. p. 724.

- ^ Bowser, Les (2016). The Settlers of Monckton Township, Omemee ON: 250th Publications.

- ^ "Biography – Simcoe, John Graves – Volume V (1801–1820) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". Biographi.ca. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ "Ontario's Mennonite Heritage". Wampumkeeper.com. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- ^ a b "Kitchener-Waterloo Ontario History – To Confederation". TransCanadaHighway.com. Retrieved October 26, 2024.

- ^ "The Walter Bean Grand River Trail – Waterloo County: The Beginning". www.walterbeantrail.ca. Retrieved September 30, 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "History of Markham, Ontario, Canada". Guidingstar.ca. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Ruprecht, Tony (December 14, 2010). Toronto's Many Faces. Dundurn. ISBN 9781459718043. Retrieved August 28, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "History" (PDF). Waterloo Historical Society 1930 Annual Meeting. Waterloo Historical Society. 1930. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ Elizabeth Bloomfield. "Building Community on the Frontier: the Mennonite contribution to shaping the Waterloo settlement to 1861" (PDF). Mhso.org. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ "Kitchener-Waterloo Ontario History – To Confederation". Kitchener.foundlocally.com. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ "York County (Ontario, Canada)". Gameo.org. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Samuel J. Steiner (2015). In Search of Promised Lands: A Religious History of Mennonites in Ontario. MennoMedia, Inc. p. 14.

- ^ Lee C. Hopple, "Spatial organization of the southeastern Pennsylvania plain Dutch group culture region to 1975." Pennsylvania Folklife 29.1 (1979): 13-26.

- ^ Rian Larkin, "Plain, Fancy and Fancy-Plain: The Pennsylvania Dutch in the 21st Century." (2018).

- ^ "African Americans and the German Language in America" (PDF). Max Kade Institute. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ^ Donald F. Durnbaugh. "Pennsylvania's Crazy Quilt of German Religious Groups". Journals.psu.edu. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ "What is Pennsylvania Dutch?". Padutch.net. May 24, 2014. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ "The Germans Come to North America". Anabaptists.org. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ Shea, John G. (December 27, 2012). Making Authentic Pennsylvania Dutch Furniture: With Measured Drawings. Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486157627 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gibbons, Phebe Earle (August 28, 1882). "Pennsylvania Dutch": And Other Essays. J.B. Lippincott & Company. p. 171. Retrieved August 28, 2017 – via Internet Archive.

Seventh Day Baptists pennsylvania dutch.

- ^ a b Murtagh, William J. (August 28, 1967). Moravian Architecture and Town Planning: Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and Other Eighteenth-Century American Settlements. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812216377. Retrieved August 28, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Donald F. Durnbaugh. "Pennsylvania's Crazy Quilt of German Religious Groups" (PDF). Journals.psu.edu. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ Murtagh, William J. (August 28, 1967). Moravian Architecture and Town Planning: Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and Other Eighteenth-Century American Settlements. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812216377. Retrieved August 28, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Elizabeth Lewis Pardoe, "Poor children and enlightened citizens: Lutheran education in America, 1748-1800." Pennsylvania History 68.2 (2001): 162-201. online

- ^ Leonard R. Riforgiato, Missionary of moderation: Henry Melchior Muhlenberg and the Lutheran Church in America (1980)

- ^ Samuel R. Zeiser, "Moravians and Lutherans: Getting beyond the Zinzendorf-Muhlenberg Impasse", Transactions of the Moravian Historical Society, 1994, Vol. 28, pp. 15–29

- ^ "Yiddish and Pennsylvania Dutch". Yiddish Book Center. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ "German Jews' Ties With Pa. Dutch Explored in Talk". The Morning Call. May 1987. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ Glenn G. Gilbert: Studies in Contact Linguistics: Essays in Honor of Glenn G. Gilbert, Austria, P. Lang, 2006, pp. 130.

- ^ American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. "American Community Survey 3-Year Estimates". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 11, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

Bibliography

- Bronner, Simon J. and Joshua R. Brown, eds. Pennsylvania Germans: An Interpretive Encyclopedia (Johns Hopkins UP, 2017), xviii, 554 pp.

- Donner, William W. " 'Neither Germans nor Englishmen, but Americans': Education, Assimilation, and Ethnicity among Nineteenth Century Pennsylvania Germans," Pennsylvania History 75.2 (2008): 197–226. online

- Eelking, Max von (1893). The German Allied Troops in the North American War of Independence, 1776–1783. Translated from German by J. G. Rosengarten. Joel Munsell's Sons, Albany, NY. LCCN 72081186.

- Grubb, Farley. "German Immigration to Pennsylvania, 1709 to 1820", Journal of Interdisciplinary History Vol. 20, No. 3 (Winter, 1990), pp. 417–436 in JSTOR

- Larkin, Rian. "Plain, Fancy and Fancy-Plain: The Pennsylvania Dutch in the 21st Century." (2018). online

- Louden, Mark L. Pennsylvania Dutch: The Story of an American Language. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016.

- McMurry, Sally, and Nancy Van Dolsen, eds. Architecture and Landscape of the Pennsylvania Germans, 1720–1920 (University of Pennsylvania Press; 2011) 250 studies their houses, churches, barns, outbuildings, commercial buildings, and landscapes

- Nolt, Steven, Foreigners in Their Own Land: Pennsylvania Germans in the Early American Republic, Penn State U. Press, 2002 ISBN 0-271-02199-3

- Pochmann, Henry A. German Culture in America: Philosophical and Literary Influences 1600–1900 (1957). 890pp; comprehensive review of German influence on Americans esp 19th century. online

- Pochmann, Henry A. and Arthur R. Schult. Bibliography of German Culture in America to 1940 (2nd ed 1982); massive listing, but no annotations.

- Roeber, A. G. Palatines, Liberty, and Property: German Lutherans in Colonial British America (1998)

- Roeber, A. G. "In German Ways? Problems and Potentials of Eighteenth-Century German Social and Emigration History", William & Mary Quarterly, Oct 1987, Vol. 44 Issue 4, pp 750–774 in JSTOR

- Von Feilitzsch, Heinrich Carl Philipp; Bartholomai, Christian Friedrich (1997). Diaries of Two Ansbach Jaegers. Translated by Burgoyne, Bruce E. Bowie, Maryland: Heritage Books. ISBN 0-7884-0655-8.

External links

Media related to German diaspora in Pennsylvania at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to German diaspora in Pennsylvania at Wikimedia Commons- The Pennsylvania German Society

- Lancaster County tourism website

- Overview of Pennsylvania German Culture

- German-American Heritage Museum of the USA in Washington, DC

- "Why the Pennsylvania German still prevails in the eastern section of the State", by George Mays, M.D.. Reading, Pa., Printed by Daniel Miller, 1904

- The Schwenkfelder Library & Heritage Center

- FamilyHart Pennsylvania Dutch Genealogy Family Pages and Database

- Alsatian Roots of Pennsylvania Dutch Firestones

- Pennsylvania Dutch Family History, Genealogy, Culture, and Life

- Several digitized books on Pennsylvania Dutch arts and crafts, design, and prints from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

- In Pennsylvania German

- German-American culture in Pennsylvania

- German diaspora in the United States

- German-Canadian culture in Ontario

- Amish in Pennsylvania

- Culture of Lancaster, Pennsylvania

- Culture of Ontario

- German diaspora in North America

- German-Jewish culture in Pennsylvania

- Indiana culture

- Maryland culture

- Mennonitism in Pennsylvania

- North Carolina culture

- Ohio culture

- Pennsylvania Dutch culture

- Virginia culture

- West Virginia culture

- Pennsylvania culture