University of Pennsylvania Law School

| University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School | |

|---|---|

| |

| Parent school | University of Pennsylvania |

| Established | 1850 (first "full professor of Law" appointed in 1792)[1][2][3] |

| School type | Private law school |

| Parent endowment | $20.7 billion (June 30, 2022)[4] |

| Dean | Sophia Z. Lee |

| Location | 3501 Sansom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States 39°57′14″N 75°11′32″W / 39.953938°N 75.192085°W |

| Enrollment | 755[5] |

| Faculty | 103[6] |

| USNWR ranking | 4th (tie) (2024)[7] |

| Bar pass rate | 97% (2019)[8][9] |

| Website | law |

| ABA profile | Standard 509 Report |

The University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School (also known as Penn Carey Law, or Penn Law) is the law school of the University of Pennsylvania, a private Ivy League research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[10] Penn Carey Law offers the degrees of Juris Doctor (J.D.), Master of Laws (LL.M.), Master of Comparative Laws (LL.C.M.), Master in Law (M.L.), and Doctor of the Science of Law (S.J.D.).

The entering class typically consists of approximately 250 students and admission is highly selective.[11] Penn Carey Law's 2020 weighted first-time bar passage rate was 98.5 percent.[9] For the class of 2024, 49 percent of students were women, 40 percent identified as persons of color, and 12 percent of students enrolled with an advanced degree.[11]

Among the school's alumni are a U.S. Supreme Court Justice, at least 76 judges of United States court system, 12 state Supreme Court Justices (with 6 serving as Chief Justice), 3 supreme court justices of foreign countries, at least 46 members of United States Congress as well as 9 Olympians, 5 of whom won 13 medals, several founders of law firms, university presidents and deans, business entrepreneurs, leaders in the public sector, and government officials.

History

[edit]18th century

[edit]

The University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School traces its origins to a series of Lectures on Law delivered in 1790 through 1792 by James Wilson,[12] one of only six signers of the United States Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution. Wilson is credited with being one of the two primary authors (the other being James Madison) of the first draft of such constitution,[13] due to his membership on the Committee of Detail[14] established by the United States Constitutional Convention on July 24, 1787, to draft a text reflecting the agreements made by the Convention up to that point.[15]: page 264

As a professor at Penn, Wilson gave these lectures on law to President George Washington and Vice President John Adams and the rest of George Washington's cabinet, including Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson.[16] Wilson was one of the original five U.S. Supreme Court associate justices nominated by George Washington and confirmed by the U.S. Senate via unanimous voice vote on September 26, 1789.[17][18] In 1792, Wilson was appointed as Penn's first full professor of law[2][3] and remained a Professor at Penn through the date of his death in 1798.[19]

19th century

[edit]In 1817, Penn trustees appointed Charles Willing Hare as the second professor of law. Hare taught for one year before becoming "afflicted with loss of reason."[20]

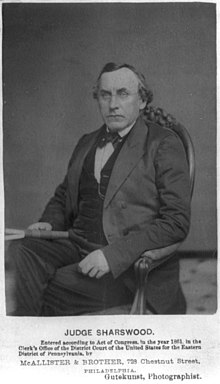

Penn began offering a full-time program in law in 1850, under the leadership of the third professor of law at the Law Department of the University of Pennsylvania, George Sharswood.[3] Sharswood was also named Dean of Penn's Law School in 1852 and served through 1867,[21] and was later appointed as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania (1879 - 1882).

In 1852, Penn was the first law school in the nation to publish a law journal. Then called The American Law Register, the University of Pennsylvania Law Review is the nation's oldest law review and one of the most-cited law journals in the world.[22]

In 1881, Carrie Burnham Kilgore became the first woman admitted to, and, in 1883, to graduate from, Penn Law, and subsequently became first woman admitted to practice law in Pennsylvania.[23] In 1888, Aaron Albert Mossell became the first African-American man to earn a law degree from Penn.[24] Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, Mossell's daughter, was awarded the Frances Sergeant Pepper fellowship in 1921 and subsequently became the first African-American to receive a PhD in economics in the United States, a degree she earned at the University of Pennsylvania.[25][26] In 1927, Alexander became the first African-American woman to graduate from Penn Law and in 1929, she became the first African-American woman to be admitted to practice law in Pennsylvania.[27]

William Draper Lewis was named dean of Penn Law in 1896.[25]

20th century

[edit]

In 1900, the trustees of the University of Pennsylvania approved his and others' request to move the Law School to the core of campus and to its current location at the intersection of 34th and Chestnut Streets.[28] Under Lewis' deanship, the Law School was one of the first schools to emphasize legal teaching by full-time professors instead of practitioners, a system that is still followed today.[28]

As legal education became more formalized, the school initiated a three-year curriculum and instituted stringent admissions requirements.

After 30 years with the Law School, Lewis founded the American Law Institute (ALI) in 1925, which was seated in the Law School and was chaired by Lewis himself. The ALI was later chaired by another Penn Law Dean, Herbert Funk Goodrich and Penn Law Professors George Wharton Pepper and Geoffrey C. Hazard Jr.

In 1969, Martha Field became the first woman to join the faculty at the Law School at Penn; she is now a professor at Harvard Law School.[25] Other notable women who have been or are presently professors at Penn Carey Law include Lani Guinier, Elizabeth Warren, Anita L. Allen, and Dorothy Roberts.

From 1974 to 1978, the dean of the Law School was Louis Pollak, who later became a federal judge. Since Pollak ascended to the bench, Penn Law's deans have included James O. Freedman, former president of Dartmouth College, Colin Diver, former president of Reed College, and Michael Fitts, current president of Tulane University.

21st century

[edit]In November 2019, the Law School received a $125 million donation from the W.P. Carey Foundation, the largest single donation to any law school to date; the school was renamed University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School, in honor of the foundation's first president, alumnus Francis J. Carey (1926–2014), who was the brother of William Polk Carey (1930 - 2012), founder of the W. P. Carey Inc. REIT, and of the charitable foundation.[29][30] The change was met by some controversy, and a petition to quash the abbreviated "Carey Law", in favor of the traditional "Penn Law", was circulated and it was agreed that the official short form name for the next few years could remain "Penn Law" and/or "Penn Carey Law".[31][32]

Osagie O. Imasogie, a 1985 graduate of Penn Law, is the current Chair of the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Board of Overseers, having replaced Perry Golkin on January 1, 2021. Imasogie has been a member of Penn Law School Board of Overseers since 2006 and more recently a Trustee on the Board of Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. Imasogie, a graduate of two law schools in Nigeria and London School of Economics and Political Science, has held senior positions with a diverse group of professional services and bio-tech companies such as GSK, DuPont, Merck, Price Waterhouse, Schnader Harrison Segal & Lewis and is presently an adjunct professor at Penn Law, where he teaches a seminar on “Intellectual Property and National Economic Value Creation”. He is the first African-born chair of an American law school.[33]

Except for the period of time during which the Law School's policy prohibited military recruiters from recruiting on the law school campus, when the military openly refused to hire gays, bisexuals and lesbians,[34] Penn Carey Law has actively supported the armed forces. The Harold Cramer Memorial Scholarship Program was established in June 2021 to ensure that all veterans admitted to the Law School will be able to afford to attend.[35]

Campus

[edit]

The University of Pennsylvania campus covers over 269 acres (~1 km2) in a contiguous area of West Philadelphia's University City district. All of Penn's schools, including the law school, and most of its research institutes are located on this campus. Much of Penn's architecture was designed by the architecture firm of Cope & Stewardson, whose principal architects combined the Gothic architecture of the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge with the local landscape to establish the Collegiate Gothic style.

The law school consists of four interconnecting buildings around a central courtyard. At the east end of the courtyard is Silverman Hall, built in 1900, housing the Levy Conference Center, classrooms, faculty offices, the Gittis Center for Clinical Legal Studies, and administrative and student offices. Directly opposite is Tanenbaum Hall, home to the Biddle Law Library several law journals, administrative offices, and student spaces. The law library houses 1,053,824 volumes and volume equivalents making it the 4th-largest law library in the country.[36] Gittis Hall sits on the north side and has new classrooms (renovated in 2006) and new and expanded faculty offices. Opposite is Golkin Hall, which contains 40,000 square feet (3,700 m2) and includes a state-of-the-art court room, 350-seat auditorium, seminar rooms, faculty and administrative offices, a two-story entry hall, and a rooftop garden.

A small row of restaurants and shops faces the law school on Sansom Street. Nearby are the Penn Bookstore, the Pottruck Center (a 115,000-square-foot (10,700 m2) multi-purpose sports activity area), the Institute of Contemporary Art, a performing arts center, and area shops.

Academics

[edit]This section contains promotional content. (April 2023) |

Admissions

[edit]For the J.D. class entering in the fall of 2022, 9.74 percent out of 6,816 applicants were offered admission, with 246 matriculating. The class boasted 25th and 75th LSAT percentiles of 166 and 173, respectively, with a median of 172.[11] The 25th and 75th undergraduate GPA percentiles were 3.61 and 3.96, respectively, with a median of 3.90.[37][38] 13 percent of matriculating students identified as first-generation college students, and 35 percent identified as first-generation professional school students.

Over 1,250 students from 70 countries applied to Penn's LLM program for the fall of 2019. The incoming class consisted of 126 students from more than 30 countries.

The entering class typically consists of approximately 250 students, and admission is highly competitive.[11] Penn Law's July 2018 weighted first-time bar passage rate was 92.09%.[9] The law school is one of the "T14" law schools, that is, schools that have consistently ranked within the top 14 law schools since U.S. News & World Report began publishing rankings.[39] In the class entering in 2018, over half of students were women, over a third identified as persons of color, and 10% of students enrolled with an advanced degree.[11]

Based on student survey responses, ABA and NALP data; 99.6 percent of the Class of 2020 obtained full-time employment after graduation. The median salary for the Class of 2019 was $190,000, as 75.2 percent of students joined law firms and 11.6 percent obtained judicial clerkships.[40] The law school was ranked #2 of all law schools nationwide by the National Law Journal, for sending the highest percentage of 2019 graduates to join the 100 largest law firms in the U.S., constituting 58.4 percent.[41]

Multidisciplinary Focus

[edit]Throughout its modern history, Penn has been known for its strong focus on inter-disciplinary studies, a character that was shaped early on by Dean William Draper Lewis.[42] Its medium-size student body and the tight integration with the rest of Penn's schools (the "One University Policy")[43] have been instrumental in achieving that aim. More than 50 percent of the Law School's courses are interdisciplinary, and it offers more than 20 joint and dual degree programs, including a JD/MBA (Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania), a JD/PhD in Communication (Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania), and a JD/MD (Perelman School of Medicine).

Various certificate programs that can be completed within the three-year JD program, e.g. in Business and Public Policy, in conjunction with the Wharton School), in Cross-Sector Innovation with the School of Social Policy & Practice, in International Business and Law with the Themis Joint Certificate with ESADE Law School in Barcelona, Spain, and in Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience (SCAN).[44][45] 19 percent of the Class of 2007 earned a certificate.[46] 57 percent of the Class of 2020 and 52 percent of the Class of 2021 pursued a Certifiate.

Penn Law also offers joint degrees with international affiliates, such as Sciences Po (France), ESADE (Spain), and the University of Hong Kong Faculty of Law. The School has further expanded its international programs with the addition of the International Internship Program, the International Summer Human Rights Program, and the Global Research Seminar, all under the umbrella of the Penn Law Global Initiative. Penn Law takes part in a number of international annual events, such as the Monroe E. Price Media Law Moot Court Competition at the University of Oxford[47] and the Waseda Transnational Program at the Waseda Law School in Tokyo.

Clinics and externships

[edit]For more than 40 years, students in Penn Law’s Gittis Center for Clinical Legal Studies have had the opportunity to learn valuable practical legal skills and put theory into practice while helping many clients in the community. The Law School offers in-house clinics, including: civil practice, criminal defense, the Detkin intellectual property and technology legal clinic, entrepreneurship, interdisciplinary child advocacy, legislative, mediation, and transnational. Students can also receive credit for completing externships with non-profit and government institutes such as the ACLU of Pennsylvania or the City of Philadelphia Law Department.

Toll Public Interest Center and related activities

[edit]Penn was the first national law school to establish a mandatory pro bono program, and the first law school to win the American Bar Association's Pro Bono Publico Award.[citation needed] The public interest center was founded in 1989 and was renamed the Toll Public Interest Center in 2006 in acknowledgement of a $10 million gift from Robert Toll (Executive Chairman of the Board of Toll Brothers) and Jane Toll. In 2011, the Tolls donated an additional $2.5 million. In October 2020, The Robert and Jane Toll Foundation announced that it was donating fifty million dollars ($50,000,000) to Penn Law, which is the largest gift in history to be devoted entirely to the training and support of public interest lawyers, and among the ten (10) largest gifts ever to a law school in the United States of America.[48] The gift expands the Toll Public Interest Scholars and Fellows Program by doubling the number of public interest graduates in the coming decade through a combination of full and partial tuition scholarships.[49] The Toll Public Interest Center has supported many students who have pursued public interest fellowships and work following graduation.

Students complete 70 hours of pro bono service as a condition of graduation. More than half of the Class of 2021 substantially exceeded the requirement. Students can create their own placements, or work through over 30 student-led organizations that focus their pro bono service in a variety of substantive areas.

The Law School awards Toll Public Interest Scholarships to accomplished public interest matriculants, and has a generous Public Interest Loan Repayment Program for graduates pursuing careers in public interest. Students interested in public interest work receive funding for summer positions through money from the student-run Equal Justice Foundation or via funding from Penn Law. Additionally, the Law School funds students interested in working internationally through the International Human Rights Fellowship.

Centers and Institutes

[edit]Penn Law hosts eleven different academic centers, institutes, programs, and research groups wherein students and faculty work together on interdisciplinary scholarship. Notable among them are the Penn Program on Regulation, directed by professor of law and political science Cary Coglianese; the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice, directed by Faculty Director Paul Heaton. Other Centers and Institutes include: Center for Asian Law; Center for Technology, Innovation, and Competition; Institute for Law and Economics; Institute for Law and Philosophy; Criminal Law Research Group; Legal History Consortium; Center for Tax Law and Policy; and Penn Program on Documentaries and the Law.

Biddle Law Library

[edit]Penn’s Law library holds over one million volumes, mostly consisting of American primary and secondary materials. Approximately one-third of the Library’s collection is composed of foreign, international, and comparative legal texts. The Library also holds subscriptions for digital resources such as LexisNexis, Westlaw, and Bloomberg Law, which provide students and faculty with access to wide breadth of journal articles, treatises, and case texts.

Biddle is also home to archives from both the American Law Institute and the American College of Bankruptcy. Biddle also holds Penn Law’s own archival collection, which consists of manuscripts, rare books, oral histories, and certain Penn Law school records.

Journals

[edit]Students at the law school publish several legal journals.[50] The flagship publication is the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, the oldest law review in the United States.[51] The University of Pennsylvania Law Review started in 1852 as the American Law Register, and was renamed to its current title in 1908.[25] It is one of the most frequently cited law journals in the world,[22] and one of the four journals that are responsible for The Bluebook, along with the Harvard, Yale, and Columbia law journals. Penn Law Review articles have captured seminal historical moments in the 19th and 20th centuries, such as the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment; the lawlessness of the first and second World Wars; the rise of the [[civil rights movement; and the war in Vietnam.[52]

Other law journals include:

- University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law,[53] one of the top 50 law journals in the United States based on citations and impact.[54]

- University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law, formerly known as Journal of International Economic Law, formerly known as Journal of International Business Law, formerly known as Journal of Comparative Business and Capital Market Law[55]

- University of Pennsylvania Journal of Business Law, formerly known as Journal of Business and Employment Law[56]

- University of Pennsylvania Journal of Law and Social Change[57]

- Asian Law Review, formerly known as East Asian Law Review, formerly known as Chinese Law and Policy Review[58]

- Journal of Law & Public Affairs[59]

U.S. Supreme Court clerkships

[edit]Since 2000, Penn has had seven alumni serve as judicial clerks at the United States Supreme Court. This record gives Penn a ranking of 10th among all law schools for supplying such law clerks for the period 2000-2019.[60] Penn has placed 48 clerks at the U.S. Supreme Court in its history, ranked 11th among law schools; this group includes Curtis R. Reitz, who is the Algernon Sydney Biddle Professor of Law, Emeritus at Penn.

Employment

[edit]According to ABA and NALP data, 99.6 percent of the Class of 2020 obtained full-time employment after graduation. The median salary for the Class of 2019 was $190,000, as 75.2 percent of students joined law firms and 11.6 percent obtained a judicial clerkship.[40] Penn combines a strong tradition in public service with being one of the top feeders of law students to the most prestigious law firms.[61] Penn Law was the first top-ranked law school to establish a mandatory pro bono requirement, and the first law school to win American Bar Association's Pro Bono Publico Award. Many students pursue public interest careers with the support of fellowship grants such as the Skadden Fellowship,[62] called by The Los Angeles Times "a legal Peace Corps."[63]

About 75 percent of each graduating class enters private practice, bringing with them the ethos of pro bono service. In 2020, the Law School placed more than 70 percent of its graduates into the United States' top law firms, maintaining Penn's rank as the number one law school in the nation for the percentage of students securing employment at these top law firms.[64][65] The Law School was ranked #4 of all law schools nationwide by Law.com in terms of sending the highest percentage of 2021 graduates to the largest 100 law firms in the U.S. (55 percent).

Based on student survey responses, ABA, and NALP data, 99.2% of the Class of 2018 obtained full-time employment after graduation, with a median salary of $180,000, as 76% of students joined law firms and 11% obtained judicial clerkships.[40] The law school was ranked # 2 of all law schools nationwide by the National Law Journal in terms of sending the highest percentage of 2018 graduates to the 100 largest law firms in the US (60%).[41]

Costs

[edit]The total cost of attendance (including tuition of $63,610, fees, living expenses, and other expenses), for J.D. students for the 2020-2021 academic year was estimated by the university to be $98,920.[66] The estimated cost of attendance increased by over 7% to $105,932 for the 2023-2024 academic year.[67]

Notable alumni

[edit]This article's list of alumni may not follow Wikipedia's verifiability policy. (September 2023) |

Judiciary

[edit]Federal Courts

[edit]

Supreme Court

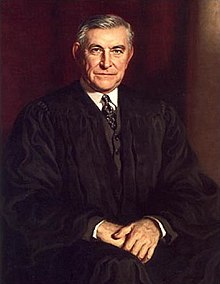

- Owen Roberts, U.S. Supreme Court Justice

Intermediary Appellate Courts

- Arlin Adams, Circuit Judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

- James Hunter III, Circuit Judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

- Harry Ellis Kalodner, Circuit Judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

- Phyllis Kravitch, Senior Circuit Judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

- Max Rosenn, Circuit Judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

- Patty Shwartz, Circuit Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

- Dolores Sloviter, Circuit Judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

- Helene N. White, Circuit Judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

Trial Courts

- Alan N. Bloch, District Judge on the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania

- Margo Kitsy Brodie, Chief District Judge on the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York

- Allison D. Burroughs, District Judge on the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts

- Rudolph Contreras, District Judge on the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia

- Herbert Allan Fogel, U.S. district judge on the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania

- Gerald Garson, New York Supreme Court Justice

- James S. Halpern, Judge on the U.S. Tax Court

- Abdul Kallon, District Judge on the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama

- John C. Knox, Chief Judge on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York

- Peter Brunswick Krauser, Chief Judge on the Court of Special Appeals of Maryland

- Juan Ramon Sánchez, Chief United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania

- Allen G. Schwartz, District Judge on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York

- Murray Merle Schwartz, District Judge on the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware

- Norma Levy Shapiro, District Judge on the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania

- Charles R. Weiner, District Judge on the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania

State Supreme Courts

[edit]- Alexander F. Barbieri (July 6, 1907 – January 1993) Penn College Class of 1929, Penn Law Class of 1932: Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court who was then appointed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in 1971 (but was defeated for election in 1971[68]

- Herbert B. Cohen, Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court

- James Harry Covington, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia

- Richard L. Gabriel, Justice of the Colorado Supreme Court

- Randy J. Holland, Justice of the Delaware Supreme Court

- William H. Lamb, (born 1940) Penn Law Class of 1965): former justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court (January 29 2003 until January of 2004)[69]

- Daniel John Layton, Chief Justice of the Delaware Supreme Court

- James T. Mitchell (November 9, 1834 – July 4, 1915) Penn Law Class of 1860:[70] Associate Justice (1889 to 1903) and Chief Justice (1903 to 1910) of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania

- Robert Nelson Cornelius Nix, Jr., Chief Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court

- Deborah Tobias Poritz, Chief Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court

- Horace Stern, Chief Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court

- George Sharswood, Chief Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court

- Leo E. Strine Jr., Chief Justice on the Delaware Supreme Court

- Karen L. Valihura, Justice of the Delaware Supreme Court[71][72]

Foreign Courts

[edit]- Gerard Hogan, Justice of the Court of Appeal of Ireland

- Yvonne Mokgoro, Justice of the Constitutional Court of South Africa

- Ayala Procaccia, Justice of the Supreme Court of Israel

- Ronald Wilson, Justice of the High Court of Australia

- Jasper Yeates Brinton, Justice of the Egyptian Supreme Court, and former U.S. Legal Advisor to Egypt

Government (Executive)

[edit]- Philip Werner Amram, Asst. Attorney General of the United States, 1939–42[73]

- John C. Bell Jr., Governor of Pennsylvania

- Louis A. Bloom, Pennsylvania State Representative (1947–1952)[74]

- William H. Brown, III, chairman, EEOC[75]

- Joseph M. Carey, Governor of Wyoming

- Gilbert F. Casellas, chairman, EEOC and General Counsel of the Air Force[76]

- Joseph Sill Clark, U.S. Senator from Pennsylvania and Mayor of Philadelphia

- Walter J. "Jay" Clayton III, chairman, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 2017–present.[77]

- Josiah E. DuBois Jr., U.S. State Department official, instrumental in Holocaust rescue[78]

- James H. Duff, Governor of Pennsylvania

- Thomas K. Finletter, U.S Secretary of the Air Force, 1950–1953; Ambassador to NATO, 1961–65[79]

- Shirley Franklin, Mayor of Atlanta, 2002–10

- Lindley Miller Garrison, U.S. Secretary of War, 1913–16[80]

- Oscar Goodman, Mayor of Las Vegas, Nevada

- William B. Gray, United States Attorney for Vermont, 1977-1981[81]

- E. Grey Lewis, general counsel of the U.S. Navy

- Jena Griswold, Colorado Secretary of State

- Henry G. Hager, Pennsylvania State Senator (1973–1984), President pro tempore of the Pennsylvania Senate (1981–1984)[82]

- Earl G. Harrison, Commissioner of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1942–44[citation needed]

- Charles A. Heimbold, Jr., Penn Law Class of 1960, U.S. Ambassador to Sweden and former chairman and CEO of Bristol-Myers Squibb Company[83]

- Henry Martyn Hoyt, Jr., Solicitor General of the United States, Governor of Pennsylvania

- Robert F. Kent, Pennsylvania State Representative (1947–1956) and Pennsylvania State Treasurer (1957–1961)[84]

- Conor Lamb, US Representative for Pennsylvania’s 17th Congressional District

- Andrew Lelling, U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts.[85]

- Lloyd Lowndes Jr., Governor of Maryland

- Albert Dutton MacDade, Pennsylvania State Senator and Judge in the Pennsylvania Court of Common Pleas[86]

- Harry Arista Mackey, Mayor of Philadelphia

- John G. McCullough, Governor of Vermont

- William M. Meredith, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, 1849–50

- Charles Robert Miller, Governor of Delaware

- Samuel W. Pennypacker, Governor of Pennsylvania

- Raul Roco, former presidential candidate and Secretary of Education in the Philippines

- Mary Gay Scanlon, US Representative for Pennsylvania’s 5th Congressional District

- Martin J. Silverstein, U.S. Ambassador to Uruguay

- Heath Tarbert, Nominee for Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for International Markets and Development in the U.S. (2017)[87]

- Robert J. Walker, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, 1840–45[88]

- Charles A. Waters, Pennsylvania State Treasurer, Pennsylvania Auditor General, and judge in the Pennsylvania Courts of Common Pleas

- George W. Wickersham, Attorney General of the United States, 1909–1913; instrumental in the breakup of Standard Oil; President of the Council on Foreign Relations (1933–36)[89]

- George Washington Woodruff, Acting U.S. Secretary of the Interior under President Theodore Roosevelt[90]

- Faith Whittlesey, United States Ambassador to Switzerland

- Chiang Wan-an, Mayor of Taipei

Academia

[edit]- Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, the first African-American woman to receive a PhD in the U.S. and graduated from Penn Law in 1927

- Anthony Amsterdam, professor at New York University School of Law

- Janice R. Bellace, first president of Singapore Management University

- Robert Butkin, dean of the University of Tulsa College of Law

- Jesse Choper, Dean of the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law

- William Draper Lewis, founder of the American Law Institute and Dean of Penn Law

- Khaled Abou El Fadl, professor of law at UCLA School of Law

- Douglas Frenkel, Morris Shuster Practice Professor of Law, director of Mediation Clinic, Penn Law

- Murray Gerstenhaber, professor of mathematics at the University of Pennsylvania

- Earl G. Harrison, Dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School

- Fred Hilmer, vice-Ccancellor of the University of New South Wales

- Caroline Burnham Kilgore, Penn Law's first female graduate (1883)

- Kit Kinports, professor of law, Polisher Family Distinguished Faculty Scholar at Penn State Law

- Roberta Rosenthal Kwall, Raymond P. Niro Professor of Intellectual Property Law, founding director of the Center for Intellectual Property Law & Information Technology at DePaul University College of Law

- William Draper Lewis, Dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School

- Peter J. Liacouras, chancellor of Temple University

- Carrie Menkel-Meadow, Chancellor’s Professor of Law at UC Irvine School of Law

- Beverly I. Moran, professor of law, Vanderbilt Law School

- Curtis Reitz, the Algernon Sydney Biddle Professor of Law at the University of Pennsylvania Law School

- Owen Roberts, Dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School, US Supreme Court Justice

- William Schnader, drafter of the Uniform Commercial Code

- Louis B. Schwartz, the Benjamin Franklin and University Professor of Law at the University of Pennsylvania Law School.

- Rodney K. Smith, president of Southern Virginia University

- Bernard Wolfman, Dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School

- Mark Yudof, president of the University of California system, Dean of the University of Texas School of Law

- John Frederick Zeller III, president of Bucknell University

Private practice

[edit]- James Harry Covington, co-founder of international law firm Covington & Burling

- Isabel Darlington, second woman to graduate from Penn Law and first to practice law in Chester County, Pennsylvania

- George Wharton Pepper, U.S. Senator from Pennsylvania, and founder of national law firm Pepper Hamilton

- Russell Duane, co-founder of international law firm Duane Morris

- Stephen Cozen, co-founder of international law firm Cozen O'Connor

- William Schnader, drafter of the Uniform Commercial Code, co-founder of national law firm Schnader Harrison Segal & Lewis

- Bernard G. Segal, chairman of Schnader Harrison Segal & Lewis

Business

[edit]- Safra Catz, CEO of Oracle Corporation

- David L. Cohen, executive vice-president of Comcast; former chief of staff to Philadelphia mayor, Ed Rendell

- Peter Detkin, co-founder of Intellectual Ventures; former vice-president and assistant general counsel at Intel

- Paul Haaga, chairman of Capital Research and Management Company, and acting CEO of NPR

- Sam Hamadeh, founder of Vault.com

- Charles A. Heimbold Jr., CEO of Bristol-Myers Squibb Company

- Gerald M. Levin, CEO of Time Warner

- Scott Mead, partner and managing director of Goldman Sachs

- Edward Benjamin Shils, professor and founder of the first research center for entrepreneurial studies in the world, at the Wharton School

- Henry Silverman, CEO of Cendant Corporation

- Gigi Sohn, founder and president of Public Knowledge

- Steven H. Temares, CEO of Bed Bath & Beyond

- Robert I. Toll, businessman who co-founded Toll Brothers

Sports

[edit]

- Irving Baxter (1876 - 1957) Penn Law Class of 1901 competed in the 1900 Olympic Games in Paris, France where he won three silver and two gold medals, winning both the high jump and pole vault competitions and placing second in the standing high jump, the standing triple jump, and the standing long jump; retired from competitive track and field without ever having lost a high jumping contest; admitted to the State Bar of New York, worked at the firm of Nash and Jones on Wall Street, appointed special judge for City of Utica, NY and U.S. Commissioner of the Northern District of New York[92]

- Anita DeFrantz, 1976 Olympic bronze medalist in the women's eight-oared shell; first woman and first African-American to represent the United States on the International Olympic Committee (IOC); first female vice president of the IOC; two-time vice president of the International Rowing Federation

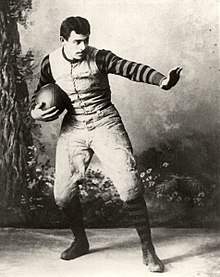

- John Heisman, namesake of the Heisman Trophy, graduated from the law school in 1892[93]

- Sarah Elizabeth Hughes, Class of 2018, (born 1985) a former competitive figure skater who is the 2002 Winter Olympics Gold Medalist Champion and the 2001 World bronze medalist in ladies' singles

- George Washington Woodruff (February 22, 1864 – March 24, 1934) Penn Law Class of 1895, Coach of Penn Crew (1892 through 1896) and Penn Football (1896 through 1901); as football coach (who originated “guards back,” “delayed pass,” and “flying interference” tactics) he compiled 124-15-2 record, including three undefeated seasons in 1894, 1895 and 1897 earning him election to the College Football Hall of Fame and his teams being recognized as national champions in 1894, 1895, and 1897;[96] also served on number of government positions, chief law officer in the National Forest Service, Acting United States secretary of the interior under President Theodore Roosevelt, Pennsylvania Attorney General, federal judge for Territory of Hawaii[90][97]

Media and the arts

[edit]- John Cromwell Bell, Jr. (Penn College Class of 1914 and Penn Law Class of 1917)[98] a founding partner of law firm Bell, Murdoch, Paxson and Dilworth (now known as Dilworth Paxson LLP),[98] appointed as Pennsylvania Secretary of Banking from 1939 to 1942, elected 18th Lieutenant Governor of Pennsylvania and Speaker of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives,[98] and for nineteen (19) days in 1947 automatically succeeded (due to resignation of incumbent Governor) to become 33rd Governor of Pennsylvania.,[99] appointed Justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania in 1951, served as Chief Justice from August 1961 until his retirement in January 1972[98][100]

- John Cromwell Bell, Sr. (Penn Law Class of 1884) served as District Attorney of Philadelphia (1903–1907), 45th Attorney General of Pennsylvania (January 17, 1911 – January 19, 1915), director of Penn's athletic program, chaired Penn Football committee, was a Penn trustee (1911–), helped found the NCAA, and served on Intercollegiate Football Rules Committee responsible for many of the rule changes made in collegiate football in its early years.[101][102][103][104]

- Renee Chenault-Fattah, co-anchor of weekday edition of WCAU NBC 10 News in Philadelphia

- Mark Haines, host on CNBC television network

- Moe Jaffe, (Wharton Undergraduate Class of 1923 and Penn Law Class of 1926) bandleader and songwriter

- El McMeen, guitarist

- Norman Pearlstine, editor-in-chief of Time

- Lisa Scottoline, author of legal thrillers

- Michael Smerconish (born 1984) Penn Law Class of 1987: American television and radio host on CNN and SiriusXM

Notable faculty

[edit]

The law school's faculty is selected to match its inter-disciplinary orientation. Seventy percent of the standing faculty hold advanced degrees beyond the JD, and more than a third hold secondary appointments in other departments at the university. The law school is well known for its corporate law group, with professors Jill Fisch and David Skeel being regularly included among the best corporate and securities law scholars in the country.[105] The School has also built a strong reputation for its law and economics group (professors Tom Baker, Jon Klick, and Natasha Sarin), its criminal law group (professors Stephanos Bibas, Leo Katz, Stephen J. Morse, Paul H. Robinson, and David Rudovsky) and its legal history group (professors Sally Gordon, Sophia Lee, Serena Mayeri, Karen Tani). Some notable Penn Law faculty members include:

- Anita L. Allen, Henry R. Silverman Professor of Law and professor of philosophy

- Tom Baker, deputy dean and insurance law

- Stephanos Bibas, criminal law scholar, current judge for the US Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

- Stephen B. Burbank, David Berger Professor for the Administration of Justice

- Cary Coglianese, Edward B. Shils Professor of Law and professor of political science; director, Penn Program on Regulation

- Douglas Frenkel, Morris Shuster Practice Professor of Law, director of Mediation Clinic

- Leo Katz, Frank Carano Professor of Law

- Jonathan Klick, Charles A. Heimbold, Jr. Professor of Law

- Michael Knoll, Theodore K. Warner Professor of Law & Professor of Real Estate; Co-Director, Center for Tax Law and Policy

- Charles ("Chuck") Mooney Jr., Charles A. Heimbold, Jr. Professor of Law

- Curtis R. Reitz, commercial law; Pennsylvania representative to the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws

- Dorothy E. Roberts, George A. Weiss University Professor of Law and Sociology and Raymond Pace and Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander Professor of Civil Rights

- Kermit Roosevelt, David Berger Professor for the Administration of Justice

- David Rudovsky, civil rights and criminal defense

- Chris William Sanchirico, Samuel A. Blank Professor of Law, Business, and Public Policy; Co-Director, Center for Tax Law and Policy

- Anthony Joseph Scirica, current judge, and former chief judge, of the US Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit[106]

- Beth Simmons, Andrea Mitchell University Professor in Law, Political Science, and Business Ethics

- Amy Wax, Robert Mundheim Professor of Law and neurologist

- Tobias Barrington Wolff, Jefferson B. Fordham Professor of Law; Deputy Dean, Alumni Engagement and Inclusion

- Christopher Yoo, John H. Chestnut Professor of Law, Communication, and Computer & Information Science; Director, Center for Technology, Innovation & Competition

The School's faculty is complemented by renowned international visitors in the frames of the Bok Visiting International Professors Program. Past and present Bok professors include Helena Alviar (Dean of Faculty of Law, University of the Andes), Pratap Bhanu Mehta (President of the Centre for Policy Research in India), Armin von Bogdandy (Director at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law), Radhika Coomaraswamy (Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations, Special Rapporteur for Children and Armed Conflict 2006-2012, Member of the UN Fact Finding Mission on Myanmar), Juan Guzmán Tapia (the first judge who prosecuted former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet), Indira Jaising (Former Additional Solicitor General of India), Maina Kiai (UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association 2011-2017), Akua Kuenyehia (Former Judge of the International Criminal Court; Former Law Dean of University of Ghana), Pratap Bhanu Mehta (President of the Centre for Policy Research in India), and Michael Trebilcock (Distinguished University Professor at the University of Toronto).

Some of Penn's former faculty members have continued their careers at other institutions (e.g., Bruce Ackerman (now at Yale), Lani Guinier (now at Harvard), Michael H. Schill (now at Oregon), Myron T. Steele (now at Virginia), and Elizabeth Warren (at Harvard until her election to the United States Senate).

References

[edit]- ^ In 1792, Associate Justice of United States Supreme Court of the United States, James Wilson, was appointed as Penn's first "full professor of law"

- ^ a b 10 U. Pa. J. Const. L. (2008) by Ewald, William, James Wilson and the Drafting of the Constitution (2008). Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law. 988. page 913

- ^ a b c "History of Penn Law". Law.upenn.edu. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ About Us | Penn Office of Investments

- ^ "University of Pennsylvania, #7 in Best Law Schools"

- ^ Penn Law School Official ABA Data Archived January 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "University of Pennsylvania (Carey)". U.S. News & World Report – Best Law Schools 2024.

- ^ "Bar Passage Rates For First-time Test Takers Soars!", by Kathryn Rubino, February 19, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c "University of Pennsylvania Law School; Ultimate Bar Passage"

- ^ "Carey Foundation rebrands universities it supports". 20 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Admissions: Entering Class Profile • Penn Law

- ^ 10 U. Pa. J. Const. L. (2008) by Ewald, William, "James Wilson and the Drafting of the Constitution" (2008). Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law. 988. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/988/ page 901 accessed April 1, 2021

- ^ 10 U. Pa. J. Const. L. (2008) by Ewald, William, "James Wilson and the Drafting of the Constitution" (2008). Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law. 988. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/988/ accessed April 1, 2021

- ^ "LII: Supreme Court: Chief Justices".

- ^ Beeman, Richard (2009). Plain Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6570-7.

- ^ Hall, Mark David (2004). "Notes and Documents: James Wilson's Law Lectures". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 128 (1): 63–76. JSTOR 20093679. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Supreme Court Nominations (1789-Present)". www.senate.gov. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ 10 U. Pa. J. Const. L. (2008) by Ewald, William, "James Wilson and the Drafting of the Constitution" (2008). Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law. 988. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/988/ page 912

- ^ Archives and Records Center. "Penn Biographies: James Wilson (1742–1798)". archives.upenn.edu/. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on May 23, 2016. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ Chamberlain, Joshua Lawrence (1901). University of Pennsylvania: Its History, Influence, Equipment and Characteristics; with Biographical Sketches and Portraits of Founders, Benefactors, Officers and Alumni. R. Herndon Company. p. 311. To read more about author, historian Joshua Chamberlain by clicking hyperlink

- ^ Brief Histories of the Schools of the University of Pennsylvania Law School | University Archives and Records Center

- ^ a b "Law Journals: Submissions and Ranking". wlu.edu. Archived from the original on 2006-03-07. Retrieved 2017-04-25.

- ^ "1880–1900: Timeline of Women at Penn, University of Pennsylvania University Archives". Archives.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on 2009-03-06. Retrieved 2023-09-19.

- ^ About: History • Penn Law

- ^ a b c d "University of Pennsylvania Law School Sesquicentennial History", University of Pennsylvania Almanac, accessed 15 Sep 2011

- ^ Malveaux, Julianne (1997). "Missed opportunity: Sadie Teller Mossell Alexander and the economics profession". In Thomas D. Boston (ed.). A Different Vision: Africa American economic thought. Vol. 1. Routledge, Chapman, & Hall. pp. 123ff. ISBN 978-0-415-12715-8. Retrieved 4 June 2013 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Sadie Alexander, Black Pioneer, Dies at 93". Ap News. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Owen Roberts, William Draper Lewis, 98 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1 (1949)

- ^ "Penn Law renamed ‘Carey Law School’ following record $125 million donation", by Manlu Liu, November 8, 2019. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- ^ "W. P. Carey Foundation makes historic $125 million gift to name Penn’s law school", by Steven Barnes, PennToday, Office of University Communications, November 8, 2019. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- ^ 'Penn Law's name change in honor of big donor is causing outcry", by Mike Stetz, The National Jurist

- ^ Liu, Manlu. "'Carey Law' changes its shortened name back to 'Penn Law' after extensive backlash".

- ^ "Osagie O. Imasogie appointed Chair of the Board of Advisors".

- ^ "Penn Law Professors Sue Defense Dept". www.law.com. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ "Penn National Gaming Launches Harold Cramer Memorial Scholarship Program to Assist Veterans Attending University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School". www.businesswire.com. 26 May 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ "University of Pennsylvania". rankingsandreviews.com.

- ^ "Entering Class Profile".

- ^ "Standard 509 Information Report".

- ^ "Prelaw Handbook Historical US News Rankings". PRELAWHANDBOOK. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ^ a b c Careers: Employment Statistics • Penn Law

- ^ a b "Ranking The Go-To Law Schools," National Law Journal

- ^ Margaret Center Klingelsmith, "History of the Department of Law of the University of Pennsylvania," The Proceedings at the Dedication of the New Building of the Department of Law, February 21st and 22nd, 1900, 16-18 (George Erasmus Nitzsche, comp. 1901).

- ^ "Pennsylvania: One University" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania Archives. 1973. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-28. Retrieved 2011-09-05.

- ^ "SCAN Certificate helps law students use neuroscience to understand human behavior". Penn Law.

- ^ "Graduate Certificate in Social, Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience (SCAN)". Center for Neuroscience and Society.

- ^ "Penn Law – Certificates of Study". Law.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on May 25, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ "2011 International Rounds in Oxford – Results". University of Oxford – Price Media Law Moot Court Programme. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ "Toll Foundation gives $50 million to Penn Law to bolster public interest lawyering". 29 September 2020.

- ^ "Robert and Jane Toll Foundation makes $50 million gift to Penn Law". 29 September 2020.

- ^ "List of Student Activities". Law.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on May 25, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ "University of Pennsylvania Law Review - PennLawReview.com". pennumbra.com.

- ^ Edwin J. Greenlee, The University of Pennsylvania Law Review: 150 Years of History, 150 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1875 (2002)

- ^ "University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law". Archived from the original on 2012-11-26. Retrieved 2019-12-24.

- ^ "Law Journals: Submissions and Ranking". Lawlib.wlu.edu. Archived from the original on March 7, 2006. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ "The Journal of International Law". Pennjil.com. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ "The University of Pennsylvania Journal of Business Law". Law.upenn.edu. November 12, 2010. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ "The Journal of Law and Social Change". Law.upenn.edu. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ "Asian Law Review". University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ "JLPA - Journal of Law & Public Affairs". The University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School.

- ^ "Law Schools That Send the Most Attorneys to United States Supreme Court Clerkships". BCGSearch.com. 2014-12-05. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ "LAW SCHOOLS REPORT". National Law Journal.

- ^ "List of Recent Fellows, Skadden Fellowship Foundation". Archived from the original on 2012-01-17. Retrieved 2011-12-25.

- ^ "Skadden Fellowship Foundation: About the Foundation". Archived from the original on October 10, 2006. Retrieved August 8, 2006. Skadden Fellowship Foundation: About the Foundation

- ^ "Ranking The Go-To Law Schools". National Law Journal. Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- ^ National Law Journal law.com. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ^ "Graduate Programs: Tuition & Fees". UPenn.edu. University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020.

- ^ "Penn Carey Law Costs". Penn Student Registration & Financial Services. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ^ "Former Senior Judges – Pennsylvania Commonwealth Court Historical Society".

- ^ "Historical List of Supreme Court Justices". Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ https://journals.psu.edu/pmhb/article/view/27326/27082 see page 6 of article in Volume XL, 1916, edition No. 1, by Hampton L. Carson retrieved on September 3 2023

- ^ "Supreme Court Justices". Archived from the original on February 12, 2015. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ "Judicial Officers of the Delaware Supreme Court". courts.delaware.gov. Archived from the original on February 12, 2015. Retrieved 2016-03-15.

- ^ Smith, J.C.; Marshall, T. (1999). Emancipation: The Making of the Black Lawyer, 1844-1944. University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated. p. 187. ISBN 9780812216851. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ "LOUIS A. BLOOM". www.legis.state.pa.us. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ Government Research Corporation; Center for Political Research; Government Research Company (1971). "The EEOC Members". National Journal. 3. Government Research Corporation: 2253. ISSN 0360-4217. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ "GILBERT F. CASELLAS". eeoc.gov. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- ^ "Jay Clayton Sworn in as Chairman of SEC". SEC.gov. 2017-05-04. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- ^ Medoff, R.; Wyman, D.S.; Eizenstat, S.; Morgenthau, H. (2009). Blowing the Whistle on Genocide: Josiah E. Dubois Jr., and the Struggle for a U.S. Response to the Holocaust. Purdue University. p. 2. ISBN 9781557535078. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ Secretaries and chiefs of staff of the United States Air Force. DIANE Publishing. 2001. p. 19. ISBN 9781428990463. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ Venzon, A.C.; Miles, P.L. (1999). The United States in the First World War: An Encyclopedia. Garland Pub. p. 250. ISBN 9780815333531. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ "Class of 1964 Obituaries: William Barton Gray". HR 1964.org. Cambridge, MA: Harvard-Radcliffe Class of 1964. 1994. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- ^ "Pennsylvania State Senate - Henry G. Hager, III Biography". www.legis.state.pa.us. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ "Heimbold, Charles A., Jr".

- ^ "Member Biography: Robert F. Kent". Pennsylvania House of Representatives Archives. Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- ^ "Meet the U.S. Attorney". www.justice.gov. 2014-12-15. Retrieved 2020-07-24.

- ^ "Albert Dutton MacDade". www.legis.state.pa.us. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ^ www.whitehouse.gov

- ^ "Robert J. Walker". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- ^ "George W. Wickersham". Notable Names Data Base. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- ^ a b "George Washington Woodruff". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on April 23, 2018. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- ^ Hertzel, Bob (July 10, 2019). "The Heisman remains the most iconic pose in sports". The Morgantown News. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ "Irving Knott Baxter".

- ^ "John Heisman (1869 - 1936)". upenn.edu.

- ^ "Sarah Hughes". Lean In. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ "Sarah Hughes". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ^ Note: Before 1936, College Football national champions have been determined by historical research and retroactive ratings and polls, which are not universally agreed upon or recognized. 1894 Poll Results recognizing Penn as National Champion was created by Parke H. Davis. 1895 Poll Results recognizing Penn as National Champion was created by Billingsley, Helms, Houlgate, National Championship Foundation. 1897 Poll Results recognizing Penn as National Champion was created by Billingsley, Helms, Houlgate, National Championship Foundation

- ^ "George Washington Woodruff". University Archives and Records Center.

- ^ a b c d "James Henderson Duff". Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission.

- ^ due to Governor Edward Martin resignation to take a seat in the United States Senate such that Bell served from January 2 to January 21, 1947, when James Duff, who had been elected in 1946 gubernatorial election, took the oath of office (the shortest of any Pennsylvania Governor)

- ^ American Leaders, 1789–1987

- ^ "How the Game of Football is Now Played". Chicago Daily Tribune. September 20, 1896. p. 33. ProQuest 175490739.

- ^ "Football Rules Revised". Washington Post. April 30, 1900. p. 8. ProQuest 144200114.

- ^ "Football Solons Meet to Adopt Rules Today". New York Times. January 27, 1908. p. 7. ProQuest 96606824.

- ^ "Forward Pass to be Changed Today". New York Times. January 25, 1908. p. 7. ProQuest 96837470.

- ^ "Corporate Practice Commentator's "Top 10" Corporate & Securities Articles for 2010," May 23, 2011.

- ^ Jeff Blumenthal (February 23, 2013), "Penn Law puts federal judge on faculty", Philadelphia Business Journal, retrieved March 1, 2013