Patsy Kelly

Patsy Kelly | |

|---|---|

Kelly in Broadway Limited (1941) | |

| Born | Sarah Veronica Rose Kelly January 12, 1910 Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Died | September 24, 1981 (aged 71) Woodland Hills, Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Calvary Cemetery, Queens, New York |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Years active | 1927–1979 |

Patsy Kelly (born Sarah Veronica Rose Kelly; January 12, 1910 – September 24, 1981) was an American actress. She is known for her role as the brash, wisecracking sidekick to Thelma Todd in a series of short comedy films produced by Hal Roach in the 1930s. Kelly's career continued in similar roles after Todd's death in 1935.

After her film career declined in the mid-1940s, Kelly returned to New York, where she worked in radio and summer stock. She also became a lifelong friend and personal assistant of Tallulah Bankhead. Kelly returned to the screen after 17 years with guest spots on television and in film roles.

Kelly returned to the stage in the 1971 revival of No, No, Nanette, for which she won a Tony Award.

Early life and early career

[edit]Youth and formative years

[edit]Kelly was born Sarah Veronica Rose Kelly in Brooklyn, New York to Irish immigrant parents John and Delia Kelly. Her father John was a police officer who left Ballinrobe, County Mayo, Ireland around 1900 to escape persecution. He died in 1942. Her mother Delia died in 1930. She was the youngest of five children, only two of whom were born in America. She acquired the nickname "Patsy" by being the butt of her family's gentle teasing and becoming the "fall guy" for many of their shenanigans. "I was always spinning and tripping about the house, usually over chairs." She was originally inspired to become a firefighter decades before the field would open to the first FDNY woman in 1982, but her mother enrolled her in a dancing school to keep her off the streets of Manhattan. In 1922 she began her entertainment career in vaudeville as a dancer at the age of 12.[1] Learning how to tap dance at Jack Blue's School of Rhythm and Tap, she befriended future talent and fellow hoofer Ruby Keeler. She had had more than her share of scrapes when she was young. She fell from a fire escape when she was seven, was struck by an automobile when she was eight, and was involved in no less than five accidents in one week at the age of nine. It was at this point her parents decided to send her to dancing school, where she broke her ankle at the end of her first week. She first attended St. Paul's Cathedral School, then Professional Children's School with Keeler.[2][circular reference]

Teenage years

[edit]In 1923, at age 13, she advanced from pupil to instructor, raking in $18 a week but coming home at nearly two or three in the morning. "So," Kelly once recalled, reminiscing about the years leading up to that, "Father Quinn, who knew about me and my tap, advised my mother to send me to dancing school. He thought perhaps that would get me interested in something besides baseball. It did. I liked the dancing and in time I began to teach in the school where I had just been studying."[3]

She performed in Frank Fay's act, first in a song-and-dance routine and later as Fay's comic foil. Her brother John W. (Willie) originally tried out for the job, but ultimately, it was Kelly who ended up landing the position at The Palace Theatre with Fay, while Willie went to work at the Waldorf Astoria, after being Fay's chauffeur for a spell.[4] "My brother didn’t care. He thought it was sissy stuff, anyhow." In one routine, Kelly told Fay and the audience that she had been at the beauty parlor. Fay remarked, "And they didn't wait on you?"[5] She remained with Fay for several seasons until Fay eventually dismissed her, either for refusing a proposal of marriage, not calling him by his surname, or refusing to travel to England.[6]

Broadway

[edit]Kelly made her Broadway debut in 1927, performing in Harry Delmar's Revels with Bert Lahr and Winnie Lightner at the Shubert Theatre. In other Broadway activity, she performed in Three Cheers (1928) with Will Rogers and Dorothy Stone, Earl Carroll's Sketch Book (1929) with William Demarest and Faith Bacon, Earl Carroll's Vanities (1930) with Jack Benny and Jimmy Savo, The Wonder Bar (1931) with Al Jolson, and in the Howard Dietz-Arthur Schwartz musical revue Flying Colors (1932) with Clifton Webb, Imogene Coca, Buddy Ebsen, and Charles Butterworth. In her later years, she appeared in No, No, Nanette (1971) with Ruby Keeler and Jack Gilford, and Irene (1973) with Debbie Reynolds.[7]

Film career

[edit]

The early 1930s

[edit]Kelly made her screen debut in a Vitaphone short subject filmed there in Brooklyn, The Grand Dame (1931), where she plays a rich gangster's moll. In 1933, reputedly after seeing her in Flying Colors, producer Hal Roach hired Kelly to team up with Thelma Todd in a series of short-subject comedies, and to replace her then-current co-star ZaSu Pitts after a contract dispute, beginning with Beauty and the Bus (1933). Pitts had demanded a salary hike of $8000 per script, so Roach terminated her services. Before making the move to Hollywood, Kelly intimated that "I'll be a flop in movies. Besides, I don't like 'em, and I never did believe there was a place called Hollywood. Somebody made it up!" She once confided to Motion Picture that, "I tried it for a few days and thought it was the silliest fool business in the world. I had to get up about five in the morning and get a lantern to light my way to the studio. I'd get there and there'd be no audience, no applause. It was like talking to myself. Someone was always hollering, 'Quiet!' or 'Hush!' My voice was always too loud or not loud enough. You had to knock yourself out with a powder puff in this business. Make up every minute. I was always hanging out a window, off the edge of a cliff, or from the side of a car going ninety miles an hour. Or I was being knocked on the bean with a pot or a pan. First day I was yelling, 'Say, where are those doubles I've heard about?' After a few days of it, I packed my duds and took a train back east."

Kelly, therefore, was quite reluctant to make the transition to films at first, but Thelma Todd encouraged her to remain in Hollywood, and so she did. Todd even drove to Pasadena to stop Kelly from returning on the train bound for New York. She also helped Kelly with her finances and tax trouble during the first few stages of her move out west. Already in debt, Todd suggested to her not to file for bankruptcy; that it would damage her credit rating. “Those were the happiest days I had in pictures,” Patsy said in 1937, “I have made more money since, but the fun Thelma and I had making those silly two-reel comedies is something that comes only once in a lifetime. Thelma was better than any tonic and taught me a lot about comedy.”[8]

Shortly after filming wrapped on Beauty and the Bus, in August 1933, Kelly was injured as a passenger in a car driven by Gene Malin, the prominent drag performer.[9] Malin apparently confused the gears and reversed off a pier into the water, after performing at the Ship Cafe, a club in Venice, Los Angeles. Malin was killed; Kelly and fellow passenger Jimmy Forlenza suffered serious injuries.[10][11] She was told by the doctors that she had only ten years left to live based on the amount of sandy water that got into her lungs, but actually survived for decades after the accident. Kelly once said that "I overheard a jury of grave-faced doctors nodding their heads over my supposedly unconscious body. They were giving me a maximum of ten years to live. Maybe they're right. When I heard that scientific verdict, I was plenty scared. But I pulled myself together and said, ‘Kelly, there’s only one way to beat this rap: don’t worry — and have fun out of the remaining years.’"[8]

The Todd-Kelly shorts cemented Kelly's image: a brash, freewheeling, fun-loving, wisecracking woman who frequently punctured the pomposity of other characters. Most were directed by Gus Meins, such as Air Fright (1933), Maid in Hollywood (1934), and Babes in the Goods (1934). Later entries in the series, such as Slightly Static (1935), showcased Kelly's dancing skills. Referring to the time she spent at the Hal Roach Studios, Kelly exclaimed: "I laughed from the time I arrived at the studio until I left at night. I was almost ashamed to take a paycheck." Kelly made 21 shorts with Todd before Todd died in 1935 of carbon monoxide poisoning after filming An All-American Toothache (1936) with Mickey Daniels and Duke York. Years later, regarding Todd's death, Kelly revealed, "She had a fight with her lover at a party that night. I wasn’t there but friends of mine were and they told me about it. There were a lot of suspicious things surrounding her death that never got explained. She most certainly wasn't drunk. Thelma used to nurse one drink for a whole evening and she never touched drugs of any kind. She was a strong New England woman with a powerful sense of humor and a wonderful zest for life. I always figured God wanted another angel. She was too young and too beautiful..."[12]

Todd was eventually replaced by the bubbly Pert Kelton for one short, Pan Handlers (1936), but Kelton was quickly replaced by Lyda Roberti, a Polish-born comedienne with a thick foreign accent. Together, they starred in the cute Hal Roach comedy Nobody's Baby (1937) just before Roberti's untimely death. According to Kelly, Roberti died of heart failure in 1938 while bending over to tie a shoelace.[13] It was incidents like these that further perpetuated Kelly's reputation as a jinx in Hollywood. And though some considered her bad luck, her performances were never hampered by this. "You see, something, darned if I know what it is, has happened to me since I came to this crazy town. Everyone I loved, turned to, needed, has gone, just like Thelma. It was Jean Malin, that swell New York actor and impersonator, first. I'd been a friend of Jean and his wife for years in New York. Then I went down to the Ship Café that night of Jean's disappearance. I glanced up at the flashing sign over the door that said, ‘Jean Malin’s last night,’ and as clearly as I'm hearing you, a voice said, ‘Be careful, it is his last night.’ He backed the car into the ocean off the end of the pier just one hour later. We were all submerged in the water. Adrenalin worked with me. It didn't with Jean."[14]

Her feature-length debut was playing the role of Jill Barker in MGM’s Going Hollywood (1933) and shared screen time with the likes of Marion Davies, Bing Crosby, Fifi D’Orsay, and Ned Sparks. The part was a little more than a mere walk-on, and she didn't have a chance to show off her musical talents in it, although the picture does contain several delightful musical moments supplied by entertainers like Crosby and The Radio Rogues.

Kelly's various film roles in the 1930s ranged from the deadpan, screwball comedic to the impressively and powerfully dramatic. There was very little she couldn't handle on screen. On the comedic side of things, she showed up in such light-hearted Americana as Pick a Star (1937) with Rosina Lawrence, Jack Haley and Laurel and Hardy, in the knee-slapping boxing comedy Kelly the Second (1936) with Guinn Williams and Charley Chase, and in the biting political satire Thanks A Million (1935) with Dick Powell, Ann Dvorak, and famed radio personality Fred Allen. As far as drama, she showed off her more serious side in films such as the politically flavored Jean Harlow vehicle The Girl From Missouri (1934) with Franchot Tone and Lionel Barrymore, and in Private Number (1936) starring Loretta Young and Basil Rathbone.

In 1935, before Todd's death, and after Stan Laurel had a falling out with Hal Roach over a contract disagreement, there was talk of Kelly joining Oliver Hardy to play his wife and Spanky McFarland’s mother in a series called The Hardy Family, but the project was jettisoned when Laurel returned to the fold. A pilot, entitled Their Night Out was announced, with James W. Horne slated to direct, but it never got past the talking stage. She was in the running to play Laurel's wife in Sons of the Desert (1933), but her part was eventually filled in by Dorothy Christy.

During the 1930s, Kelly also appeared in musicals like Going Hollywood (1933), the college football extravaganza Pigskin Parade (1936) with Stuart Erwin and Judy Garland (in her first film role), playing second banana in Sing, Baby, Sing (1936) with Gregory Ratoff, Adolphe Menjou, and Ted Healy, and in Paramount Pictures' Every Night at Eight (1935), playing one of a trio of hopeful singers (the other two played by Alice Faye and Frances Langford) who are discovered by an ambitious, blue-collar bandleader by the name of Tops Cardona sympathetically played by George Raft who christens them "The Swanee Sisters". In the film, Kelly gets to showcase her singing talents by crooning out Jimmy McHugh-Dorothy Fields melodies such as the light and breezy "I Feel a Song Coming On" and "Speaking Confidentially". The movie introduced the world to the song "I'm in the Mood for Love", which is sung by Langford. The tap-dancing she learned when she was young was put to good use in films like 20th Century Fox's Thanks a Million and Warner Bros.' Go Into Your Dance (1935) starring Ruby Keeler and Al Jolson in their only screen pairing together. According to columnist Ruth White: "Wherever you find a laughing group on a sound stage, you will find Patsy in the center of it. She's everybody's friend, as kindly to the prop boys as she is with the most famous stars... This jolly picture thief... makes picture work such play that not until the film is previewed do her co-stars realize she has stolen the show."[8]

The later 1930s and early 1940s

[edit]In 1936, she told an interviewer: "Of course I was fortunate in having enjoyed a long and fairly successful stage career before going to Hollywood, but just the same, I had to start all over again as there is as much difference between stage and screen acting technique as there is between day and night... The average small-town girl who comes to Movieland without previous stage or screen experience will find the road ahead rough and heartbreaking at times."[15]

In 1937, she was sent to a sanitarium to go on a diet and she lost fifty pounds. Though the new, slimmer Kelly didn't last too long, she was quite proud of her accomplishment. "Look! I can almost hide behind Gary Cooper sideways!"[citation needed]

By the end of the decade, she appeared as shopgirl Peggy O' Brien in Hal Roach's There Goes My Heart (1938) starring Fredric March and Virginia Bruce playing Alan Mowbray's love interest, and as Kitty in The Gorilla (1939) featuring a creepy Bela Lugosi and the always delightfully zany and offbeat Ritz Brothers, a performance she once cited as the favorite performance of her own. In the early 1940s, her proficient acting and comedic talents got her to rub elbows and share the screen with big-named stars such as John Barrymore (in his final film role), Gary Cooper, Merle Oberon, Walter Brennan, John Wayne, Bert Lahr, Lupe Velez, Eddie Albert, Victor McLaglen, and even Phil Silvers and Ann Miller in their big-screen debut, Hit Parade of 1941. She also co-starred with her predecessor ZaSu Pitts in Roach's train comedy Broadway Limited (1941) around this period. Familiar faces that appear frequently in her films include Si Jenks, Douglas Fowley, Charlie Hall, Marion Davies, Don Barclay, and Arthur Housman.

In her films, one could find her often playing a sassy maid or an assistant, as she did in features like Page Miss Glory, The Gorilla, Topper Returns, and Merrily We Live. Subsequently, these comic supporting roles were a harbinger of things to come for Kelly. She jested that she was often cast as a maid, "...because I had a maid's costume that fit. They didn’t have to get me a new outfit. They lent it from one studio to another."[8]

After appearing in a film or two for RKO, she then began starring in low-budget fare such as My Son, The Hero (1943) with Roscoe Karns and Maxie Rosenbloom, and Danger! Women at Work (1943), pictures released by Producers Releasing Corporation.

Later career

[edit]Kelly's film career had stalled after being blackballed by the studios for outing herself as a lesbian.[16] After leaving Hollywood, Kelly returned to New York City where she worked in radio with personalities such as Barry Wood on NBC's The Palmolive Party (which was broadcast on Saturday nights at 10 p.m.), toured the U.S. and Canada to entertain the troops during WWII, and did summer stock theatre in shows like My Sister Eileen and On the Town. She also worked as a personal assistant to Tallulah Bankhead and appeared with her on stage in Dear Charles (1955). She later moved into Bankhead's mansion "Windows" in Bedford Village, New York acting as her domestic, or "guest resident".[13][17]

Kelly returned to the screen in the 1950s with television and sporadic film roles. On television she appeared in guest roles on 26 Men, Kraft Television Theatre, The Man from U.N.C.L.E, The Dick Van Dyke Show, The Wild Wild West, and Alfred Hitchcock Presents, as well as many unsold pilots. During the 1960s, she made memorable appearances as Mac the Nurse in The Naked Kiss (1964) and as Laura-Louise McBirney in the psychological horror film Rosemary's Baby (1968), directed by Roman Polanski, alongside veteran actors Sidney Blackmer, Ruth Gordon, Ralph Bellamy, and Maurice Evans.

She returned to Broadway in 1971 in the revival of No, No, Nanette with fellow hoofers Ruby Keeler and Helen Gallagher. Kelly scored a huge success as the wisecracking, tap-dancing maid, and won Broadway's 1971 Tony Award for Best Featured Actress in a Musical for her performance in the show.[1] She matched that success the following year when she starred in Irene with Debbie Reynolds, and was again nominated for a Tony.[18]

In 1976, she appeared as the housekeeper Mrs. Schmauss in the Walt Disney film Freaky Friday starring Jodie Foster and Barbara Harris. Her last role in a feature film was in another comedy for Disney, The North Avenue Irregulars (1979), also co-starring Harris, along with Cloris Leachman, Edward Herrmann and Karen Valentine. Kelly's final onscreen appearance was a guest spot in a two-part episode of The Love Boat in 1979.

She continued appearing in film and television roles until she suffered a stroke in January 1980 that limited her ability to speak.

Personal life

[edit]This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (September 2024) |

Kelly was gay, but her sexuality was unknown to the public. She told a biographer that she was a "big dyke," but forbid him to publish that information until her career was over; it was published in 1994.[19] She had obscurely hinted at her sexual orientation during the 1930s, when she revealed to Motion Picture magazine she had been sharing an apartment with actress Wilma Cox for several years with no intention of getting married; but she never publicly claimed to be a lesbian, which in those days would have resulted in great social and professional criticism.[20] She later confirmed that she had an affair with Tallulah Bankhead when she worked as her personal assistant.[17][21]

It was once reported that she was once temporarily engaged to a serviceman named Otto Malde in 1942, but the marriage never materialized. "It doesn't matter to me whether you are a private, sergeant, or lieutenant," she told the press, "but I guess we'll just have to wait."[22]

Kelly loved food and eventually learned how to cook well. She said, "I will go out of my way anytime to get a shrimp cocktail." As far as desserts, she enjoyed apple and lemon pie, gelatins, ice cream, and peach shortcake, which she had a special recipe for. "I am mad about bread. "I especially like hot biscuits and out on the Coast we have a southern cook who can make more kinds of hot breads than I ever knew existed. And in the morning, I like coffee cake and crumb cake, especially if they are homemade." She was known to have an affinity for sauces. She was also fond of mashed potatoes. "Mash them; and if I were a man, I'd marry you any time." On Sundays, she would entertain guests and serve chicken, turkey or roast beef. She was also wild about sweet potatoes topped with marshmallows. "They taste like a million dollars," proclaimed Kelly. "Steak I like in any way," she added, "and I like string beans, either creamed or just with butter, mashed turnips, orange squash, and creamed spinach. And if you want to make me divinely happy, give me spareribs and cabbage."[23]

A rabid film fan herself, she spent many a fun-filled evening going to the movies, sometimes seeing seven or eight a week. "What do you do on the two other nights?" she was asked. "Well... there's really nothing for me to do. I just sit around wishing there were more pictures to see. But, when you see eight or ten pictures a week, the supply really runs out." When not toddling off to go see a picture show, she spent her off time playing cards with friends or penny roulette on Redondo Beach.[24]

When asked if she went to go see any stage shows, she answered, "Well, when I go East and see some shows," she said, "the crowds and the overtures make me feel sort of tingly. But I wouldn't trade it for Hollywood. Actually, I’m probably the most rabid movie fan in town. I see a picture almost every night. This is a crazy place. If you go places and drink, people talk. If you don't drink and don't go places, they still talk. I don't care what they say because I don't do night clubs and big parties. People drop in here and we play badminton. I like to play at night. Sometimes we play a little poker. Ted Healy is my best customer, he and Jack Haley and a few others. I don't do much else. Once I took up golf, but I lost five balls on the first two holes, so I said to hell with that. When I'm trying to reduce I ride two bicycles and get beaten up by a masseuse. I'm generally trying to reduce because the thing I enjoy most is eating. The way I usually look before starting work on a picture, my stomach would get on the screen three seconds before I arrived. I still hoof around the house a little. But Eleanor Powell doesn't have to worry... All this time you've never had to ask for anything... a job or a new contract or more money or better parts. It seems too good to last. Things just happen."[25]

In January 1980, Kelly suffered a stroke while in San Francisco that caused her to lose the ability to speak. She was admitted to Englewood Nursing Home in Englewood, New Jersey, on the advice of her old friend Ruby Keeler, where she underwent therapy.[26]

Death

[edit]On September 24, 1981, Kelly died of cancer at the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital in Woodland Hills, California.[27][28] Her funeral was held on September 28 at St. Malachy Roman Catholic Church in Manhattan. She is interred alongside her parents, John and Delia Kelly, in Calvary Cemetery in Queens, New York.[29]

For her contribution to the motion picture industry, she has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6669 Hollywood Boulevard, right near Musso & Frank Grill.

Credits

[edit]Stage

| Year | Title | Role | Performance dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1927 | Harry Delmar's Revels | various | (Nov 28, 1927 - Mar 1928) |

| 1928 | Three Cheers | Bobbie Bird | (Oct 15, 1928 - Apr 13, 1929) |

| 1929 | Earl Carroll's Sketch Book | various | (Jul 01, 1929 - Jun 07, 1930) |

| 1930 | Earl Carroll's Vanities | various | (Jul 01, 1930 - Jan 03, 1931) |

| 1931 | The Wonder Bar | Electra Pivonka | (Mar 17, 1931 - May 29, 1931) |

| 1932 | Flying Colors | Lessie Bevis/Mrs. McVitty | (Sep 15, 1932 - Jan 25, 1933) |

| 1955 | Dear Charles | Madame Bouchemin | (Sep 15, 1954 - Jan 29, 1955) |

| 1971 | No, No, Nanette | Pauline | (Jan 07, 1971 - Oct 28, 1972) |

| 1973 | Irene | Mrs. O'Dare | (Mar 13, 1973 - May 3, 1975) |

Short subjects

- The Grand Dame (1931)

- Beauty and the Bus (1933) teamed with Thelma Todd

- Backs to Nature (1933) teamed with Thelma Todd

- Air Fright (1933) teamed with Thelma Todd

- Babes in the Goods (1934) teamed with Thelma Todd

- Soup and Fish (1934) teamed with Thelma Todd

- Roamin' Vandals (1934)

- Maid in Hollywood (1934) teamed with Thelma Todd

- I'll Be Suing You (1934) teamed with Thelma Todd

- Three Chumps Ahead (1934) teamed with Thelma Todd

- One-Horse Farmers (1934) teamed with Thelma Todd

- Opened By Mistake (1934) teamed with Thelma Todd

- Done In Oil (1934) teamed with Thelma Todd

- Bum Voyage (1934) teamed with Thelma Todd

- Treasure Blues (1935) teamed with Thelma Todd

- Sing Sister Sing (1935) teamed with Thelma Todd

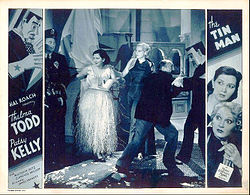

- The Tin Man (1935) teamed with Thelma Todd

- The Misses Stooge (1935) teamed with Thelma Todd

- Slightly Static (1935) teamed with Thelma Todd

- Twin Triplets (1935) teamed with Thelma Todd

- Hot Money (1935) teamed with Thelma Todd

- Top Flat (1935) teamed with Thelma Todd

- An All-American Toothache (1936) teamed with Thelma Todd

- Pan Handlers (1936) teamed with Pert Kelton

- At Sea Ashore (1936) teamed with Lyda Roberti

- Hill-Tillies (1936) teamed with Lyda Roberti

- Babies, They're Wonderful! (1947)

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1929 | A Single Man | uncredited/unknown/bit | silent film |

| 1933 | Going Hollywood | Jill Barker | |

| 1934 | The Countess of Monte Cristo | Mimi Schmidt | |

| 1934 | The Girl from Missouri | Kitty Lennihan | |

| 1934 | The Party's Over | Mabel | |

| 1934 | Transatlantic Merry-Go-Round | Patsy Clarke | |

| 1935 | Go into Your Dance | Irma 'Toledo' Knight | |

| 1935 | Every Night at Eight | Daphne O' Connor | |

| 1935 | Page Miss Glory | Betty | |

| 1935 | Thanks a Million | Phoebe Mason | |

| 1936 | Private Number | Gracie | |

| 1936 | Kelly the Second | Molly Patricia Kelly | First starring feature film |

| 1936 | Sing, Baby, Sing | Fitz | |

| 1936 | Pigskin Parade | Bessie Winters | Alternative title: Harmony Parade |

| 1937 | Nobody's Baby | Kitty Reilly | |

| 1937 | Pick a Star | Nellie Moore | |

| 1937 | Ever Since Eve | Sadie Day, aka Susie Wilson | |

| 1937 | Wake Up and Live | Patsy Kane | |

| 1938 | Merrily We Live | Etta | |

| 1938 | There Goes My Heart | Peggy O'Brien | |

| 1938 | The Cowboy and the Lady | Katie Callahan | |

| 1939 | The Gorilla | Kitty | |

| 1940 | Hit Parade of 1941 | Judy Abbott | Alternative title: Romance and Rhythm |

| 1941 | Road Show | Jinx | |

| 1941 | Topper Returns | Emily | |

| 1941 | Broadway Limited | Patsy Riley | |

| 1941 | Playmates | Lulu Monahan | |

| 1942 | Sing Your Worries Away | Bebe McGuire | |

| 1942 | In Old California | Helga | |

| 1943 | Ladies' Day | Hazel Jones | |

| 1943 | My Son, the Hero | Gertie Rosenthal | |

| 1943 | Danger! Women at Work | Terry Olsen | Last starring feature film |

| 1960 | Please Don't Eat the Daisies | Maggie | |

| 1960 | The Crowded Sky | Gertrude Ross | |

| 1964 | The Naked Kiss | Mac, the Head Nurse | |

| 1966 | The Ghost in the Invisible Bikini | Myrtle Forbush | |

| 1967 | C'mon, Let's Live a Little | Mrs. Fitts | |

| 1968 | Rosemary's Baby | Laura-Louise McBirney | |

| 1970 | The Phynx | Herself | |

| 1976 | Freaky Friday | Mrs. Schmauss | |

| 1979 | The North Avenue Irregulars | Mrs. Rose Rafferty / Blarney Stone, Irregular | Alternative title: Hill's Angels |

TV credits

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1952-53 | All Star Revue | Various | 6 episodes |

| 1955 | Lux Video Theatre | Season 5 Episode 24: "One Foot in Heaven" | |

| 1957 | Kraft Television Theatre | Season 10 Episode 43: "The Big Break" | |

| 1959 | 26 Men | Big Kate | Season 2 Episode 30: "The Last Kill" |

| 1960 | Laramie | Bea | Season 1 Episode 19: "The Legend of Lily" |

| 1960 | The Untouchables | Slapsie Sadie | Season 1 Episode 27: "Head of Fire: Feet of Clay" |

| 1960 | Alfred Hitchcock Presents | Minnie Redwing | Season 6 Episode 7: "Outlaw in Town" |

| 1962 | The Dick Van Dyke Show | Juror | Season 1 Episode 24: "One Angry Man" |

| 1962 | Pete and Gladys | Katy | Season 2 Episode 33: "The Case of the Gossipy Maid" |

| 1963 | Arrest and Trial | Catalina Sorelli | Season 1 Episode 1: "Call It a Lifetime" |

| 1964 | Burke's Law | Agatha Beauregard / Big Mouth Annie | Season 1 Episode 27: "Who Killed WHO IV?" and "Who Killed Mr. Cartwheel" |

| 1964 | Burke's Law | Big Mouth Annie | Season 2 Episode 6: "Who Killed Mr. Cartwheel?" |

| 1966 | Vacation Playhouse | Miss Primrose | Season 4 Episode 6: "My Son, The Doctor" |

| 1966 | The Wild Wild West | Prudence Fortune | Season 2 Episode 4: "The Night of the Big Blast" |

| 1967 | The Wild Wild West | Mrs. Bancroft | "The Night of the Bogus Bandits" |

| 1967 | The Man from U.N.C.L.E. | Mama Sweet | Season 3 Episode 22: "The Hula Doll Affair" |

| 1967 | Laredo | Abbie Heffernan | Season 2 Episode 23: "A Question of Guilt" |

| 1968 | Bonanza | Mrs. Neeley | Season 9 Episode 16: "A Girl Named George" |

| 1969 | Love, American Style | Mrs. Hennessy | Season 1 Episode 6 (Segment: "Love and the Watchdog") |

| 1969 | The Pigeon | Mrs. Macready, the Landlady | Television movie |

| 1970 | Barefoot in the Park | Old Lady | Season 1 Episode 1: Pilot |

| 1975-1976 | The Cop and the Kid | Brigid Murphy | 11 episodes |

| 1979 | The Love Boat | Mabel Hopkins | Season 3 Episode 10: "The Love Lamp Is Lit/Critical Success/Rent a Family/Take My Boyfriend, Please/The Man in Her Life: Part 1" |

| 1979 | The Love Boat | Mabel Hopkins | Season 3 Episode 11: "The Love Lamp Is Lit/Critical Success/Rent a Family/Take My Boyfriend, Please/The Man in Her Life: Part 2" |

Recordings

[edit]"I'm Gonna Hang My Hat On The Tree That Grows in Brooklyn" (Shapiro/Pescal/Cherig) played by Al Goodman and His Orchestra. Sung by Patsy Kelly and Barry Wood; V-Disc, Nov. 1944

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "'Company' Takes 6 Honors At Tony Awards". Ocala Star-Banner. March 29, 1971. p. 5B. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ Professional Children's School

- ^ Pleshette, M. (1971, May 11). “Comeback of Star’s Best Friend.” Reading Eagle, p. 13.

- ^ Byrne, James P.; Coleman, Philip; King, Jason Francis (2008). Ireland and the Americas. ABC-CLIO. p. 326. ISBN 978-1-851-09614-5.

- ^ S.D., Trav (2006). No Applause--Just Throw Money: The Book That Made Vaudeville Famous. Macmillan. p. 183. ISBN 0-865-47958-5.

- ^ Cullen, Frank (2004). Vaudeville Old & New: An Encyclopedia of Variety Performers in America, Volume 1. Vol. 1. Psychology Press. p. 627. ISBN 0-415-93853-8.

- ^ "Patsy Kelly". Internet Broadway Database. The Broadway League. Archived from the original on May 14, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Brideson, C., & Brideson, S. (2012). The High Priestess of The Bourgeoisies. In Also starring...: Forty biographical essays on the greatest character actors of Hollywood's Golden Era, 1930-1965. essay, Bear Manor Media.

- ^ "Backs Car Over Pier; Is Killed, Two Hurt". The Lewiston Daily Sun. August 11, 1933. p. 1. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ "Jean Malin Killed, Patsy Kelly Injured". The Norwalk Hour. August 11, 1933. p. 15. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ "Entertainer Dies In Auto Plunge". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. August 11, 1933. p. 7. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ Donati, W., 2012. The life and death of Thelma Todd. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland.

- ^ a b Thomas, Bob (November 25, 1959). "Patsy Kelly Goes Back To Films After 16 Years". Toledo Blade. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ Parish, James Robert, and William T. Leonard. The Funsters, Arlington House, New Rochelle, 1979, p. 360.

- ^ Unknown. “Film Fame is Not a “Cinch’ Says Patsy Kelly, Movie Star.” The Victoria Advocate 11 November 1936. Page 3. Print.

- ^ "Patsy Kelly". masterworks broadway. Sony. 2022. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Monush, Barry (2003). The Encyclopedia of Hollywood Film Actors: From the Silent Era to 1965, Volume 1. Vol. 1. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 388. ISBN 1-557-83551-9.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (August 11, 1972). "Revival of 'Irene' to Open the Astor". The New York Times.

- ^ Gever, Martha (2003). Entertaining Lesbians: Celebrity, Sexuality, and Self-Invention (1 ed.). Routledge. p. 210. ISBN 0-415-94480-5.

- ^ Faderman, Lillian; Timmons, Stuart (2006). Gay L. A.: A History of Social Vagrants, Hollywood Rejects, And Lipstick Lesbians. Basic Books. p. 62. ISBN 0-465-02288-X.

- ^ https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/2824-the-witch-upstairs-patsy-kelly-in-rosemary-s-baby [bare URL]

- ^ Associated Press. (1942, June 5). "Patsy Still Single." The Mercury, p. 8.

- ^ Heffernan, Harold. “‘Stop Worrying, Eat Anything,’ Is Patsy’s Creed.” The Milwaukee Journal 2 May 1937. Page 6. Print.

- ^ Lincoln Nebraska State Journal Archives, Aug 25, 1935, p. 26, 25 Aug. 1935, p. 26.

- ^ "The Pittsburgh Press - Google News Archive Search".

- ^ "Patsy Recovering From Loss Of Speech". Boca Raton News. May 4, 1980. p. 7B. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ "Actress Patsy Kelly dies of cancer". Eugene Register-Guard. September 24, 1981. p. 3A.

- ^ Flints, Peter B. (September 26, 1981). "PATSY KELLY, ACTRESS IS DEAD: PLAYED COMIC ROLES IN FILMS". The New York Times. p. 28. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ Wilson, Scott (August 19, 2016). Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed. McFarland. p. 398. ISBN 978-1-4766-2599-7. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Patsy Kelly at the Internet Broadway Database

- Patsy Kelly at IMDb

- Patsy Kelly at the TCM Movie Database

- Patsy Kelly at Find a Grave

Further reading

[edit]- Maltin, Leonard (2015) [First published 1969]. "Patsy Kelly". The Real Stars : Profiles and Interviews of Hollywood's Unsung Featured Players (softcover) (Sixth / eBook ed.). Great Britain: CreateSpace Independent. pp. 166–186. ISBN 978-1-5116-4485-3.

- Neibaur, J. L. (2018). The Hal Roach Comedy Shorts of Thelma Todd, ZaSu Pitts and Patsy Kelly. United States: McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4766-7255-7

- Hadleigh, Boze (2016). Hollywood Lesbians: From Garbo to Foster. United States: Riverdale Avenue Books. ISBN 978-1-6260-1299-8

- 1910 births

- 1981 deaths

- 20th-century American actresses

- Actresses from Brooklyn

- American female dancers

- American film actresses

- American musical theatre actresses

- American people of Irish descent

- American radio actresses

- American stage actresses

- American television actresses

- Burials at Calvary Cemetery (Queens)

- Deaths from cancer in California

- Hal Roach Studios actors

- American lesbian actresses

- LGBTQ people from New York (state)

- Hal Roach Studios short film series

- Musicians from Brooklyn

- American vaudeville performers

- 20th-century American singers

- 20th-century American women singers

- Dancers from New York (state)

- 20th-century American dancers

- 20th-century American LGBTQ people