Hexaemeron

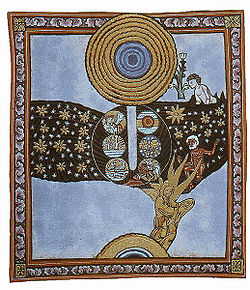

The term Hexaemeron (Greek: Ἡ Ἑξαήμερος Δημιουργία Hē Hexaēmeros Dēmiourgia), literally "six days," is used in one of two senses. In one sense, it refers to the Genesis creation narrative spanning Genesis 1:1–2:3:[1] corresponding to the creation of the light (day 1); the sky (day 2); the earth, seas, and vegetation (day 3); the sun and moon (day 4); animals of the air and sea (day 5); and land animals and humans (day 6). God then rests from his work on the seventh day of creation, the Sabbath.[2]

In a second sense, the Genesis creation narrative inspired a didactic[3] genre of Jewish and Christian literature known as the Hexaemeral literature.[4] Literary treatments in this genre are called Hexaemeron.[2] This literature was dedicated to the composition of commentaries, homilies, and treatises concerned with the exegesis of the biblical creation narrative through ancient and medieval times and with expounding the meaning of the six days as well as the origins of the world.[5] The first Christian example of this genre was the Hexaemeron of Basil of Caesarea, and many other works went on to be written from authors including Augustine of Hippo, Jacob of Serugh, Jacob of Edessa, Bonaventure, and so on. These treatises would become popular and often cover a wide variety of topics, including cosmology, science, theology, theological anthropology, and God's nature.[6] The word can also sometimes denote more passing or incidental descriptions or discussions on the six days of creation,[7] such as in the brief occurrences that appear in Quranic cosmology.[8]

The Church Fathers wrote many Hexaemeron and a diversity of opinions existed on a broad range of subjects. Two general modes of interpretation existed, corresponding to the literal form of interpretation, represented by the tradition of the School of Antioch (one example being in John Chrysostom), and another represented by an allegorical mode of interpretation, represented by the tradition of the School of Alexandria (examples being Origen and Augustine).[9] Outside of this categorization, however, individuals in each school would not necessarily deny the validity of the alternative perspective. Despite the differences, consensus existed on a number of subjects among these interpreters, including in their belief in God's primacy as the Creator; the occurrence of creation through the act of the divine Word (Christ) and the Spirit; on the created and not eternal nature of the world, God's creation of both the spiritual and material realms (including the human body and soul); and the continuing providential care over the creation by God. The Church Fathers primarily focused on the first two chapters of Genesis, as well as a few essential statements in the New Testament (John 1:1–4; 1 Corinthians 8:6).[10]

Etymology

[edit]The word derives its name from the Greek roots hexa-, meaning "six", and hemer-, meaning "day". The word hexaemeric refers to that which pertains to a hexaemeron, and this is to be distinguished from hexaemeral, that which occurs in six parts.[citation needed]

In Latinized writing, the spelling Hexameron can also be found.[11]

History of the genre

[edit]Origins

[edit]The first extant witness was Philo of Alexandria's De opificio mundi, though he was not the founder of the genre: an earlier work in the genre that Philo had known of had been composed by Aristobulus of Alexandria. Though other such works from the Jewish tradition are thought to have existed from this era, none have survived or were known to later Christian exegetes.[12]

Late antiquity

[edit]Saint Basil delivered a lecture series over the course of three days during 378 AD on the Genesis creation narrative. Using the information he had prepared for this, he wrote his Hexaemeron, which spanned nine homilies. This text figures as the earliest extant Christian Hexaemeron, and the first one since that of Philo's.[13] He opened his Hexaemeron as follows[14]:

If sometimes on a bright night, whilst gazing with watchful eyes on the inexpressible beauty of the stars, you have thought of the Creator of all things; if you have asked yourself who it is that has dotted the heaven with such flowers, and why visible things are even more useful than beautiful; if sometimes in the day you have studied the marvels of light, if you have raised yourself by visible things to the invisible being, then you are a well prepared auditor, and you can take your place in this august and blessed amphitheatre.

It was widely influential, being translated into multiple languages and resulting in the composition of many other Hexaemeron among his own contemporaries, including his brother Gregory of Nyssa and Ambrose.[15]

Among the Latin Fathers, Ambrose and Augustine of Hippo wrote some of the earliest extant hexaemeral literature. Ambrose's Hexaemeron is heavily influenced by Basil's work of the same name. In contrast, Augustine wrote several works that serve as commentaries on the Genesis narrative, including the final section of The Confessions and De Genesi ad litteram (published in 416).[16]

The first Hexaemeron in the Syriac language was the Hexaemeron of Jacob of Serugh in the early sixth century, including one homily dedicated to each of the creation days.[13][17] Later, the prolific Syriac theologian Jacob of Edessa wrote his own Hexaemeron in the first years of the eighth century as his final work.[18]

Medieval and early modern period

[edit]Many Hexaemeral works were composed during the Middle Ages, including by Bede (7th century), Peter Abelard (12th century), and Robert Grosseteste (13th century).[19] The genre extended into early modern times with the Sepmaines of Du Bartas, and Paradise Lost by John Milton. According to Alban Forcione[20] the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century saw ‘hexameral theatre’, and in particular the visionary holism represented by the De la creación del mundo (1615) of Alonso de Acevedo. There is a cusp between Du Bartas, very influential in his time, and Milton: Milton's different approach marks the effective literary end of the genre. The approach continued in an important literary role until the seventeenth century.

The six days

[edit]Meaning of "six days"

[edit]According to Philo of Alexandria, an allegorical reader of the creation week in the tradition of the School of Alexandria, the six days do not constitute a reference to periods of time but instead reflect the necessity of expressing the chronological order of the order of creation using human numbers. Some readers who agreed with this mode of thought suggested various reasons as to why six was chosen as the number of days: Augustine, who alongside many others (including Origen, Clement of Alexandria, and Gregory of Nyssa) believed that the entire creation was instantaneous, considered that the figure of six for the number of days was chosen because it was a perfect number that reflected the sum of its sixth (1), its third (2), and its half (3).[21] Other allegorical or numerological readings were also proposed.[22] For proponents of the School of Antioch, the six days were a straightforward and literal historical reference. Various ideas were circulated as to why God would create over the course of six days instead of instantaneously: a common one hinged on the necessity of gradual creation.[23]

Day one

[edit]The Book of Genesis opens with the statement that "In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth" (Gen 1:1). Many Christians linked this to the opening verse of the Gospel of John: "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God" (John 1:1). For Origen, these statements together are not of a temporal beginning but instead about the creation of all things through the Logos. In the reading of Ambrose, "In this beginning, that is, in Christ, God created heaven and earth." For Augustine, the statements reflect both a beginning in Christ and a temporal beginning. The statement in Genesis about the creation of the heaven and Earth for Basil was about the creation of an invisible realm to benefit all beings that love God followed by the creation of a visible realm whereby human affairs could take place. Ambrose agreed that a spiritual realm already existed at the time that the physical one was created. By contrast, Ephrem the Syrian and John Chrysostom denied any allegorical element to Genesis 1:1, believing it referred to the actual substance of both heaven and Earth: the heavens and the Earth were created alike to the formation of the roof and then the foundation of the physical world. Theophilus of Antioch likewise conceived of a box-like cosmos as being implied by the passage. Augustine thought that the 'heaven and Earth' signified the spiritual created order and unformed matter. John Scotus Eriugena believed that the terms referred to archetypes and primordial causes. Next, Genesis states that the world was created "without form and void" or, in the Septuagint, "invisible and unfinished" (aoratos kai akataskeuastos). For Ephrem, this signifies that the formation of the elements post-dated the void. According to Theophilus, this passage demonstrates that the formless matter did not exist always but was created by God. The terms "darkness" and "deep" that then appear refer to an absence of light and/or an extreme depth of water that prevents seeing. Gregory of Nyssa, Basil's brother, agreed that the text is referring to water, light, the earth and stars. Ephrem thought the darkness was due to the presence of clouds which must have then been created on the first day. For Eriugena, the phraseology of the Earth being 'empty and void' and the phrase 'darkness upon the deep' are uses because the human intellect cannot fathom the primordial causes. In Gen 1:2, the Spirit hovering above the waters signified, according to Basil, that the Holy Spirit was already working on preparing the way for the creation of life. John Chrysostom read the passage similarly. 'Let there be light' (Gen 1:3) was about the creation of intelligible light, and it was also a universal light that came before the sun, moon, and so on. Augustine, noting that the creation of angels was not mentioned by Genesis, reads a reference to the creation of angels here.[24]

Day two

[edit]Genesis refers to the creation of the 'heaven' (firmament) that separated the upper and lower waters in the second day. Philo believed that the heaven was the first visible entity to be created. Basil saw the firmament as a firm substance separating the bottom air from the air above it, with the air above being of a lower density. The firmament also balances the evaporation and precipitation of water and served to separate different levels of atmospheric moisture enabling the existence of the correct climate needed for living things. For Eriugena, the second to sixth days represent the creation of the visible elements of the cosmos.[25]

Day three

[edit]On the third day, Genesis says that the waters below the firmament were gathered in order that dry places appear. Philo understands this to have been a process that unmingled a more formless entity into the distinct elements of earth and water. Saltwater was gathered into one place and dew watered the dry regions such that fruits and other foods for consumption could grow. Ambrose argued that because the sun would only be created on the fourth day, the drying out of water over land regions must have been done directly by God. John of Damascus contemplated both allegorical and literal readings, the former implicating a division of the cosmic elements, with the latter implicating a collection of water to be used for the prosperity of organic life. Eriugena thought that the dry land was a reference to essential form and the water a reference to all bodies composed of the four elements (formed matter). The phrase "Let the earth put forth vegetation, plants yielding seed, and fruit trees bearing fruit in which is their seed, each according to its kind, upon the earth." Philo commented on the abundance of seeds, fruit, and more in as food for animals and as the initiation of a process that led to the creation of more and similar fruits. Plant seeds contain specific principles that periodically mature, such that God endows nature with a long duration. John Chrysostom believed God was the one who primarily brought for plants that could be eaten per this verse, as opposed to the workings of the sun (which would be created on the following day) or the actions of farmers.[26]

Day four

[edit]In the fourth day, God creates the heavenly luminaries: the sun, moon, and stars. Philo sought to understand this in terms of the greater order, whereby the sun came after the plants: he found in this a refutation of astrology which tries to explain all things by the movement of such bodies. However, God's creation of vegetation before these light-giving bodies demonstrates God's dominion as opposed to any of these bodies. Basil agreed with and continued this line of argument. John of Damascus believed that the moon took its light from the sun (a widely held view sometimes analogized to the Church taking its light from Christ, such as by Origen[27]): he also offers in his commentary on this statement an accurate description of lunar and solar eclipses, and the differences between a lunar and solar year.[28] Basil also confronted the issue of the existence of light before the fourth day, since the sun was only created then: this stemmed from the continuous movement of the light of God formed when God said "Let there be light".[27]

Day five

[edit]The creation of animals on the fifth day, for Philo, corresponded in some manner to their having five senses (sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch). Basil emphasized that the fifth day was the first time that creatures with senses and thought were made. He also offered a bulk of zoological insights in his commentary on the fifth day. Basil also thought that the common origins of members like fins and wings from the waters helped to explain the similarities in their movements. John of Damascus saw birds as linking together the water, from whence they originated, the earth, where they live, and the air, where they fly.[29]

Day six

[edit]Basil commented that when the earth was commanded to bring forth living creatures, this importantly involved it being endowed with the ability to bring forth creatures in general. The succeeding statement that God saw the created creatures as "good" was taken by John Chrysostom to mean that upon closer analysis, even living forms which appear useless to humans might come to be found to be beneficial: all things were created with reason. The reference to the making of man in the image of God (Gen 1:27) was taken by Augustine to have involved the endowment of humans with souls and intelligence. Mammals were made alongside humans in the sixth day due to their greater similarity to humans. The statement that each animal is created according to its kind, for Basil, signified the creation of a process of uninterrupted succession of each kind of organism through reproduction.[30]

List of Hexaemeron

[edit]Until the first century

[edit]- A now-lost work by Aristobulus of Alexandria.

- The De opificio mundi by Philo of Alexandria (ca. 1st century)

Fourth to seventh centuries

[edit]- The Hexaemeron of Basil of Caesarea (ca. 4th century)

- The In Hexaemeron of Gregory of Nyssa, the brother of Basil[31]

- The Hexaemeron of Ambrose, Hexaemeron, in Latin and the most influential[32]

- The De Genesi ad litteram of Augustine of Hippo, 401–415,[33] influenced by Plato and Greek biology[34]

- The Commentary on the Hexameron of Pseudo-Eustathius in Greek

- The Hexaemeron of Jacob of Serugh, (ca. 5–6th century), in Syriac[35]

- The De opificio mundi by John Philoponus (ca. 6th century)

- The Hexaemeron of Jacob of Edessa, (ca. 6–7th century), completed later by George, Bishop of the Arabs

- The Hexaemeron of Anastasius Sinaita (ca. 700)

Eighth century onwards

[edit]- In Genesim by Bede (ca. 8th century)

- The Quaestiones in Genesim by Alcuin (ca. 756)

- The Hexaemeron of Anastasius Sinaita

- The Hexaemeron of John Scotus Eriugena (ca. 9th century)

- The Hexaemeron of John the Exarch, (ca. 9th century), Preslav, Bulgaria[36]

- The Hexaemeron of Ælfric of Abingdon (ca. 10th century)

- The Hexaemeron of Peter Abelard (ca. 12th century)

- The Hexaemeron of Thierry of Chartres (ca. 12th century)

- The Hexaemeron of Honorius Augustodunensis (ca. 12th century)[37][38]

- The Hexaemeron of Anders Sunesen (ca. late 12th century)

- The Hexaemeron of Robert Grosseteste, (ca. 1230)

- The Collationes in Hexaemeron by Bonaventure (ca. 1273)

- The Hexaemeron of Henry of Ghent (ca. 13th century)[39]

- The Lecturae super Genesim of Henry of Langenstein (1385)[40]

See also

[edit]- Allegorical interpretations of Genesis

- Ancient near eastern cosmology

- Biblical cosmology

- Framework interpretation (Genesis)

- Six Ages of the World

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Brown 2019, p. 12.

- ^ a b Sarna 1966, p. 1–2.

- ^ Christopher Kendrick, Milton: A Study in Ideology and Form (1986), p. 125.

- ^ Gasper 2024.

- ^ Brown 2019, p. 20.

- ^ Katsos 2023, p. 15–16.

- ^ Robbins 1912, p. 1–2.

- ^ Decharneux 2023, p. 128.

- ^ Decharneux 2023, p. 172–173.

- ^ De Beer 2015.

- ^ Brown 2019, p. 12n38.

- ^ Matusova 2010, p. 1–2.

- ^ a b Tumara 2024, p. 170.

- ^ Gasper 2024, p. 176.

- ^ Kochańczyk-Bonińska 2016.

- ^ St. Augustine on Genesis, translated with notes by Edmund Hill, O. P., New City Press, 2002. Technically, Augustine wrote three commentaries on Genesis: On Genesis: A Refutation of the Manichees (c.388/389); De Genesi ad litteram Imperfectus (393-395); and De Genesi ad litteram (begun c. 400, published 416). See Hill, pp. 13-15, 165 for more information on the dating of and relationship between these books.

- ^ Mathews Jr. 2009, p. 1.

- ^ Romeny 2008, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Gasper 2024, p. 183–189.

- ^ Cervantes’ Night-Errantry: The Deliverance of the Imagination, in Jeremy Robbins, Edwin Williamson, E. C. Riley (editors), Cervantes: Essays in Memory of E. C. Riley, p. 43.

- ^ De Beer 2015, p. 5–8.

- ^ Brown 2019, p. 18, 21.

- ^ Decharneux 2023, p. 173.

- ^ De Beer 2015, p. 8–13.

- ^ De Beer 2015, p. 14.

- ^ De Beer 2015, p. 15–16.

- ^ a b Gasper 2024, p. 182.

- ^ De Beer 2015, p. 16–17.

- ^ De Beer 2015, p. 17–18.

- ^ De Beer 2015, p. 18–20.

- ^ DeMarco 2014.

- ^ Glacken, p. 174.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Glacken, p. 196.

- ^ "Jacob of Serugh's "Hexaemeron"". www.peeters-leuven.be. Archived from the original on 2018-05-29. Retrieved 2019-09-14.

- ^ Dekker, Simeon (2021). "Parenthetical verbs as elements of diatribe in John the Exarch's Hexaemeron". Die Welt der Slaven (in German). 66 (2): 238–267. doi:10.13173/WS.66.2.238.

- ^ Crouse 1978.

- ^ Cizewski 1985.

- ^ Smalley, B. (1953). "A Commentary on the Hexaemeron by Henry of Ghent". Recherches de théologie ancienne et médiévale. 20: 60–101. ISSN 0034-1266. JSTOR 26186099.

- ^ Nicholas H. Steneck (1976), Science and creation in the Middle Ages. Henry of Langenstein (d. 1397) on Genesis

Sources

[edit]- Brown, Andrew J. (2019). The Days of Creation: A History of Christian Interpretation of Genesis 1:1–2:3–4. Brill.

- Cizewski, Wanda (1985). "Interpreting the Hexaemeron: Honorius Augustodunensis De Neocosmo". Florilegium. 7 (1): 84–108. doi:10.3138/flor.7.006.

- Crouse, R.D. (1978). "INTENTIO MOYSI: Bede, Augustine, Eriugena and Plato in the Hexaemeron of Honorius Augstodunensis". Dionysius. 2.

- Decharneux, Julien (2023). Creation and Contemplation The Cosmology of the Qur'ān and Its Late Antique Background. De Gruyter.

- DeMarco, David C. (2014). "The Presentation and Reception of Basil's Homiliae in hexaemeron in Gregory's In hexaemeron". Zeitschrift für antikes Christentum/Journal of Ancient Christianity. 17 (2): 332–352. doi:10.1515/zac-2013-0017.

- De Beer, Wynand (2015). "The Patristic Understanding of the Six Days (Hexaemeron)". Journal of Early Christian History. 5 (2): 3–23. doi:10.1080/2222582X.2015.11877324.

- Gasper, Giles (2024). "On the Six Days of Creation: The Hexaemeral Tradition". In Goroncy, Jason (ed.). T&T Clark Handbook of the Doctrine of Creation. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 176–190.

- Katsos, Isidoros (2023). The Metaphysics of Light in the Hexaemeral Literature: From Philo of Alexandria to Gregory of Nyssa. Oxford University Press.

- Kochańczyk-Bonińska, Karolina (2016). "The Concept Of The Cosmos According To Basil The Great's On The Hexaemeron" (PDF). Studia Pelplinskie. 48: 161–169.

- Mathews Jr. (2009). Jacob of Sarug's homilies on the six days of creation. The first day. Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1607243236.

- Matusova, Ekaterina (2010). "Allegorical interpretation of the Pentateuch in Alexandria: inscribing Aristobulus and Philo in a wider literary context". The Studia Philonica Annual. 22: 1–51.

- Sarna, Nahum (1966). Understanding Genesis: Through Rabbinic Tradition and Modern Scholarship. The Jewish Theological Seminary Press.

- Robbins, Frank Egleston (1912). The Hexaemeral Literature: A Study of the Greek and Latin Commentaries on Genesis. University of Chicago Press.

- Romeny, Bas Ter Haar (2008). "Jacob of Edessa on Genesis: His Quotations of the Peshitta and his Revision of the Text". In Romeny, Bas Ter Haar (ed.). Jacob of Edessa and the Syriac Culture of His Day. Brill. pp. 145–158.

- Tumara, Nebojsa (2024). "Creation in Syriac Christianity". In Goroncy, Jason (ed.). T&T Clark Handbook of the Doctrine of Creation. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 164–175.

Further reading

[edit]- Dellie, Eudoxie. "Bibliographie secondaire sélective sur les Hexaéméra et les thématiques rattachées," Almagest (2020). Link.

- Allert, Craig. Early Christian Readings of Genesis One: Patristic Exegesis and Literal Interpretation, InterVarsity Press, 2018.

- Bouteneff, Peter. Beginnings: Ancient Christian Readings of the Biblical Creation Narratives, Baker Academic, 2008.

- Brown, Andrew J. The Days of Creation: A History of Christian Interpretation of Genesis 1:1–2:3–4, Brill, 2019.

- Corcoran, Mary Irma. Milton's Paradise with Reference to the Hexameral Background, 1945.

- Fox, Michael A.E. Augustinian hexameral exegesis in Anglo-Saxon England : Bede, Alcuin, AElfric and Old English biblical verse, 1997.

- Freibergs, Gunar. "The Medieval Latin Hexameron from Bede to Grosseteste," Ph.D. dissertation (unpublished), University of Southern California, 1981.

- Goroncy, Jason (ed). T&T Clark Handbook of the Doctrine of Creation, Bloomsbury, 2024.

- Grant, E. Science and Religion, 400 BC-AD 1550: From Aristotle to Copernicus. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

- Grypeou, Emmanouela and Helen Spurling. The Book of Genesis in Late Antiquity: Encounters Between Jewish and Christian Exegesis, Brill, 2013.

- Kuehn, C. and J. Baggarly, eds. and trans. Anastasius of Sinai: Hexaemeron (OCA 278). Rome: Pontificio Istituto Orientale, 2007.

- Louth, Andrews. "The Six Days of Creation According to the Greek Fathers" in Reading Genesis after Darwin, Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Rasmussen, Adam. Genesis and Cosmology: Basil and Origen on Genesis 1 and Cosmogony, Brill, 2019.

- Rudolph, Conrad, "In the Beginning: Theories and Images of Creation in Northern Europe in the Twelfth Century," Art History 22 (1999) 3-55

- Williams, Arnold. The Common Expositor: An Account of the Commentaries on Genesis, 1527-1633, The University of North Carolina Press, 1948.

- Young, Frances. God's Presence: A Contemporary Recapitulation of Early Christianity, Cambridge University Press, 2013, pp. 44–91.

External links

[edit]- Hexaemeron.ro - How to read Genesis - Hieromonk Serafim Rose

- The Hexaemeron by Anastasius of Sinaita

The Hexaemeron public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Hexaemeron public domain audiobook at LibriVox