Pat Garrett

Pat Garrett | |

|---|---|

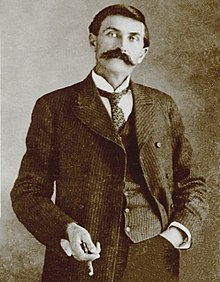

Garrett c. 1903 | |

| Born | Patrick Floyd Jarvis Garrett June 5, 1850 |

| Died | February 29, 1908 (aged 57) |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound |

| Resting place |

32°18′4.118″N 106°47′7.908″W / 32.30114389°N 106.78553000°W |

| Known for | Killing William H. Bonney (Billy the Kid) |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 8 |

| Signature | |

Patrick Floyd Jarvis Garrett (June 5, 1850 – February 29, 1908) was an American Old West lawman, bartender and customs agent known for killing Billy the Kid. He was the sheriff of Lincoln County, New Mexico, as well as Doña Ana County, New Mexico.

Early years

[edit]Patrick Floyd Jarvis Garrett was born on June 5, 1850, in Chambers County, Alabama. He was the second of five children born to John Lumpkin Garrett and his wife Elizabeth Ann Jarvis. Garrett's four siblings were Margaret, Elizabeth, John, and Alfred.[1] Garrett was of English ancestry, and his ancestors migrated to America from the English counties of Hertfordshire, Northamptonshire, Bedfordshire, Lincolnshire and Buckinghamshire.[2] When Pat was three years old his father purchased the John Greer plantation in Claiborne Parish, Louisiana. The Civil War, however, destroyed the Garrett family's finances. Their mother died at the age of 37 on March 25, 1867, when Garrett was 16. The following year, on February 5, 1868, his father died at age 45. The children were left with a plantation that was more than $30,000 in debt. The children were taken in by relatives. The 18-year-old Garrett headed west from Louisiana on January 25, 1869.[1]: 9 [3]

Buffalo hunter

[edit]Garrett's whereabouts over the next seven years are obscure. By 1876 he was in Texas hunting buffalo. During this period Garrett killed his first man, another buffalo hunter named Joe Briscoe. Garrett surrendered to the authorities at Fort Griffin, Texas, but they declined to prosecute.[1]: 29–31 When buffalo hunting declined, Garrett left Texas and rode to New Mexico Territory.[4][5] When Garrett arrived at Fort Sumner, New Mexico, he found work as a bartender, then as a cowboy for Pedro Menard "Pete" Maxwell.

Family life

[edit]Garrett's first wife was Juanita Martinez (born May 1860 in Taos, New Mexico). Garrett and Juanita married in the fall of 1879. Tom O'Folliard, Charlie Bowdre and Billy the Kid, among others, attended the wedding.[citation needed] As guests watched Garrett and his wife dancing at a celebration of their recent wedding, she collapsed, dying the next day. She was 19.[6][7] [8] She was interred in Fort Sumner Cemetery.[9]

The reference Leon C. Metz made about Juanita being the older sister of Pat's second wife Apolonia is unfounded. Apolonia had only one sister by the name of Celsa Gutierrez.[1] On January 14, 1880, Garrett married Apolinaria Gutierrez.[1]: 40–41 [10] Between 1881 and 1905 Apolinaria Garrett gave birth to eight children: Ida, Dudley, Elizabeth, Annie, Patrick, Pauline, Oscar, and Jarvis.

Pursuit of Billy the Kid

[edit]

Billy the Kid, William Henry Bonney Jr, born Henry McCarty was wanted for murder in the aftermath of the Lincoln County War. On November 2, 1880, Garrett was elected sheriff of Lincoln County, New Mexico, having defeated the incumbent, Sheriff George Kimball, by a vote of 320 to 179.[11] Although Garrett's term would not begin until January 1, 1881, Sheriff Kimball appointed him a deputy sheriff for the remainder of Kimball's term. Garrett also obtained a deputy U.S. Marshal's commission, which allowed him to pursue the Kid across state lines. Garrett and his posse stormed the Dedrick ranch at Bosque Grande on November 30, 1880. They expected to find the Kid there, but only succeeded in capturing John Joshua Webb, who had been charged with murder, along with an accused horse thief named George Davis.[12][13] Garrett turned Webb and Davis over to the sheriff of San Miguel County a few days later, and moved on to the settlement of Puerto de Luna. There a local tough named Mariano Leiva picked a fight with Garrett and was shot in the shoulder.[14][15][16]

On December 19, 1880, Billy the Kid, Charlie Bowdre, Tom Pickett, Billy Wilson, Dave Rudabaugh, and Tom O'Folliard rode into Fort Sumner. Lying in wait were deputy Garrett and his posse. Mistaking O'Folliard for the Kid, Garrett's men opened fire and killed O'Folliard.[17] Billy and the others escaped unharmed. Three days later, Garrett's posse cornered Billy and his companions at a spot called Stinking Springs. They killed Bowdre and captured the others.[18][19] On April 15, 1881, Billy the Kid was sentenced to hang by Judge Warren Bristol, but escaped thirteen days later, killing two deputies.[20][21]

On July 14, 1881, Garrett visited Fort Sumner to question a friend of the Kid's about his whereabouts and learned he was staying with a common friend, Pedro Menard "Pete" Maxwell. Around midnight, Garrett went to Maxwell's house. The Kid was asleep in another part of the house, but woke up in the middle of the night and entered Maxwell's bedroom, where Garrett was standing in the shadows. The Kid did not recognize the man standing in the dark. He asked him, repeatedly, "¿Quién es?" ("Who is it?"), and Garrett replied by shooting at him twice.[22] The first shot hit the Kid in the chest just above the heart, while the second missed. Garrett's account leaves it unclear whether Billy was killed instantly or took some time to die.[23]

Account of Billy the Kid

[edit]He coauthored The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid with Ash Upson,[24] and for decades his book was deemed authoritative.[25]

Following Billy the Kid's death, writers quickly went to work producing books and articles that made a folk hero out of him, while making Garrett seem like an assassin. Although filled with many errors of fact, The Authentic Life served afterward as the main source for most books written about the Kid until the 1960s.[26][27][28] A failure when originally released, an original copy of the Pat Garrett–Ash Upson book became a rare commodity; in 1969 the original 1882 edition of the Garrett–Upson book was described by Ramon F. Adams as being "exceedingly rare".[29] Twentieth-century editions of Garrett's Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid (with alterations to the original title) appeared in 1927,[30] 1946[31] and 1964.[32]

Texas Ranger

[edit]Garrett did not seek re-election as sheriff of Lincoln County in 1882. He moved to Texas, where he ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the state senate. Garrett became a captain with the Texas Rangers for less than a month, then returned to Roswell, New Mexico.[34]

Middle years

[edit]Irrigation investments and move to Texas

[edit]Garrett discovered a large reservoir of artesian water in the Roswell region and went into partnership with two men to organize the "Pecos Valley Irrigation and Investment Company" on July 18, 1885.[35] Garrett kept his irrigation schemes alive for several years, and on January 15, 1887, he purchased a one-third interest in the "Texas Irrigation Ditch Company", but the partners got rid of him. On August 15, 1887, he formed a partnership with William L. Holloman in the "Holloman and Garrett Ditch Company".[36] All of Garrett's forays into the irrigation field, however, resulted in failure.[citation needed] By 1892, Garrett had moved his large family to Uvalde, Texas, where he became a close friend of John Nance Garner (1868–1967), a future vice president of the United States.[37] Garrett might have lived out the remainder of his life in Uvalde, had it not been for a headline-making event back in New Mexico.

Disappearance of Albert Jennings Fountain

[edit]On January 31, 1896, Colonel Albert Jennings Fountain and his eight-year-old son Henry disappeared at the edge of the White Sands area of southern New Mexico. Neither of the Fountains were ever seen again. The mystery was never officially solved, even with the efforts of Apache scouts, the Pinkertons, and an all-out push by the Republican Party.[38] In April 1896, Garrett was appointed sheriff of Doña Ana County, and two years later had gathered sufficient evidence to make arrests, asking a judge in Las Cruces for warrants to arrest Oliver M. Lee, William McNew, Bill Carr and James Gililland. Within hours, he had arrested McNew and Carr.[39][40]

During the early morning hours of July 12, 1898 Garrett and his posse confronted Oliver M. Lee and James Gililland at a spot called "Wildy Well" near Orogrande, New Mexico. Garrett had hoped to capture the fugitives while they were sleeping, but Lee and Gililland expected trouble and took their bedrolls up to the roof of the bunkhouse to avoid being taken by surprise. One of Garrett's deputies named Kearney heard footsteps on the roof, scaled a ladder, and was mortally wounded by the fugitives. A stray shot nicked Garrett. Due to his concern for his dying deputy, Garrett arranged a truce with the fugitives and withdrew while Kearney was lifted into a wagon. Kearney, however, died on the road to Las Cruces, and Lee and Gililland remained at large for another eight months, before they finally surrendered to Sheriff George Curry.[41] They were found not guilty in the Fountain killings, and the indictments for killing the deputy were also dismissed.[42][43]

Final kill

[edit]Garrett killed his last offender in 1899, a fugitive named Norman Newman, who was wanted for murder in Greer County, Oklahoma. Newman was hiding out at the San Augustin Ranch in New Mexico. Sheriff George Blalock of Greer County went to New Mexico and asked Garrett for his assistance. The lawmen and Jose Espalin, one of Garrett's deputies, rode to the ranch, and on October 7, 1899, Newman was killed in a gunfight.[44][45]

Presidential appointment in El Paso

[edit]On December 16, 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt nominated Garrett to the post of collector of customs in El Paso.[46] He also became one of President Roosevelt's three "White House Gunfighters" (Bat Masterson and Ben Daniels being the others).[47] Despite public outcry over his appointment, Garrett was confirmed by the U.S. Senate on January 2, 1902.[48] Garrett's tenure as El Paso's collector of customs was stormy from the start. On May 8, 1903, he got into a public fistfight with an employee named George Gaither. The following morning, both Garrett and Gaither paid five dollar fines for disturbing the peace.[49] Continued complaints about Garrett's alleged incompetence were sent to Washington.[50] Through it all, President Roosevelt stood by Garrett. As a show of his support, Roosevelt invited Garrett to attend a Rough Riders reunion being held in San Antonio during April 1905. Since Garrett had not been a member of that regiment, Roosevelt's invitation was taken as a snub at those critics who wanted Garrett replaced from his post. Garrett brought a guest of his own to the event named Tom Powers. Garrett introduced Powers to the president as "a prominent Texas cattleman." Garrett and Powers posed for two photographs with Roosevelt, first standing with him in a group and later seated with Roosevelt at dinner.[51] Garrett's enemies obtained copies of the photos and sent them to Roosevelt, informing the president that instead of being the "cattleman" that Garrett claimed, Powers was, in fact, the owner of a "notorious dive" in El Paso called the Coney Island Saloon. That was the final straw for Roosevelt, who replaced Garrett with a new collector of customs on January 2, 1906.[52]

Late years

[edit]Financial problems

[edit]Following his dismissal, Garrett returned with his family to New Mexico. Garrett was in deep financial difficulty. His ranch had been heavily mortgaged, and when he was unable to make payments, the county auctioned off all of Garrett's personal possessions to satisfy judgments against him. The total from the auction came to $650.[53] President Roosevelt had appointed Pat's friend George Curry as the territorial governor of New Mexico. Garrett met with Curry, who promised him the position of superintendent of the territorial prison at Santa Fe, once he was inaugurated. Since Curry's inauguration was still months away, the destitute Garrett left his family in New Mexico and returned to El Paso, where he found employment with the real estate firm of H.M. Maple and Company. During this period Garrett moved in with a woman known as "Mrs. Brown", who was described as an El Paso prostitute.[54] When Governor-elect Curry learned of his involvement with Brown, the promised appointment of prison superintendent was withdrawn.[55]

Last conflict and death

[edit]

Dudley Poe Garrett, Pat's son, had signed a five-year lease for his Bear Canyon Ranch with Jesse Wayne Brazel.[56][57] Garrett and his son objected when Brazel began bringing in large herds of goats, which were anathema to cattlemen like Garrett. Garrett tried to break the lease when he learned that the money for Brazel's operation had been put up by his neighbor, W. W. "Bill" Cox. He was further angered when he learned that Archie Prentice "Print" Rhode was Brazel's partner in the huge goat herd.[57] When Brazel refused, the matter went to court. At this point James B. Miller met with Garrett to try to solve the problem. Miller met with Brazel, who agreed to cancel his lease with Garrett – provided a buyer could be found for his herd of 1,200 goats. Carl Adamson, who was related to Miller by marriage, agreed to buy the 1,200 goats. Just when the matter seemed resolved, Brazel claimed that he had "miscounted" his goat herd, claiming there were actually 1,800 – rather than his previous estimate of 1,200. Adamson refused to buy that many goats, but agreed to meet with Garrett and Brazel to see if they could reach some sort of agreement.

Garrett and Carl Adamson rode together, heading from Las Cruces, New Mexico, in Adamson's wagon. Brazel appeared on horseback along the way. Garrett was shot and killed, but exactly by whom remains the subject of controversy. Brazel and Adamson left the body by the side of the road and returned to Las Cruces, where Brazel surrendered to Deputy Sheriff Felipe Lucero. More than thirty years later, Lucero claimed that Brazel exclaimed, "Lock me up. I've just killed Pat Garrett!" Brazel then pointed to Adamson and said, "He saw the whole thing and knows that I shot in self-defense."[58] Lucero incarcerated Brazel, summoned a coroner's jury, and rode to Garrett's death site. Brazel's trial for Garrett's murder concluded on May 4, 1909.[59] Brazel was represented at his trial by attorney and future Secretary of the Interior Albert Bacon Fall. The only eyewitness to Garrett's murder, Adamson, never appeared at the trial, which lasted only one day and ended with an acquittal.[60][61][62]

Identity of the murderer

[edit]The coroner's report on Garrett's death states that Brazel shot Garrett.[63] Brazel reportedly confessed, but was acquitted at trial. Four other suspects have been proposed: Adamson, Cox, Rhode, and Miller. In a book published in 1970, Glenn Shirley gave his reasons for naming Miller as the killer of Pat Garrett.[64] Leon C. Metz in his 1974 biography of Garrett related the claim of W. T. Moyers that "his investigations led him to believe that [W. W.] Cox himself ambushed and killed Garrett,"[65] but also wrote that "[t]he Garrett family believes that Carl Adamson pulled the trigger."[66] In his 2010 book on Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett, Mark Lee Gardner suggests that Archie Prentice "Print" Rhode killed Garrett.[67]

Death site

[edit]

The site of Garrett's death is now commemorated by a historical marker south of U.S. Route 70, between Las Cruces, New Mexico and the San Augustin Pass.[68][69] The historical marker is located about 1.2 miles from where Garrett was murdered. In 1940 his son, Jarvis Garrett, marked the spot with a monument consisting of concrete laid around a stone with a cross carved in it. The cross is believed to be the work of Garrett's mother. Scratched in the concrete is "P. Garrett" and the date of his killing. The marker is located in the desert.[70] In 2020, the city of Las Cruces revealed plans for a development that would destroy the site. An organization called Friends of Pat Garrett has been formed to ensure that the city preserves the site and marker.[71][72]

Funeral and burial site

[edit]At six feet five inches,[73][a] Garrett's body was too tall for any finished coffins available, so a special one had to be shipped in from El Paso. His funeral service was held March 5, 1908, and he was laid to rest next to his daughter, Ida, who had died in 1896 at the age of fifteen. Garrett's grave and the graves of his descendants are in the Masonic Cemetery, Las Cruces.[72]

Portrayals

[edit]Garrett has been a character in many films and television shows, and has been portrayed by:

- Wallace Beery in Billy the Kid (1930)

- Wade Boteler in Billy the Kid Returns (1938)

- Brian Donlevy in Billy the Kid (1941)

- Thomas Mitchell in The Outlaw (1943)

- Charles Bickford in Four Faces West (1948)

- Monte Hale in Outcasts of the Trail (1949)

- Robert Lowery in I Shot Billy the Kid (1950)

- Frank Wilcox in The Kid from Texas (1950)

- Scott Douglas in the NBC-TV series, Omnibus (1952, 1 episode)

- James Griffith in The Law vs. Billy the Kid (1954)

- Richard Travis in the syndicated half-hour TV series, Stories of the Century (1954)

- Keith Richards in the syndicated half-hour TV series, Buffalo Bill, Jr. (1955, 1 episode)

- Bob Duncan in The Parson and the Outlaw (1957)

- John Dehner in The Left Handed Gun (1958)

- George Montgomery in Badman's Country (1958)

- Rhodes Reason in the ABC-TV series, Bronco (1958, 1 episode)

- Walter Sande in the half-hour CBS series, Wanted: Dead or Alive (1958, episode 26, "The Eager Man")

- Wayne Heffley in the half-hour ABC-TV series, Colt .45 (1959 episode entitled "Amnesty")

- Barry Sullivan (1960) in the half-hour NBC-TV series The Tall Man, co-starring Clu Gulager as Billy the Kid

- Rod Cameron in Le pistole non discutono (1964)

- Allen Case in the ABC series, The Time Tunnel (1966, 1 episode)

- Fausto Tozzi in El hombre que mató a Billy el Niño (1967)

- Glenn Corbett in Chisum (1970)

- Rod Cameron in The Last Movie (1971)

- James Coburn in Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973)

- Patrick Wayne in Young Guns (1988)

- Duncan Regehr in Gore Vidal's Billy the Kid (1989)

- William Petersen in Young Guns II (1990)

- Joe Zimmerman in the TV documentary series, Unsolved History (2002, 1 episode) and in the Discovery Channel's cable documentary Discovery Quest: Billy the Kid Unmasked (2004)

- Michael Paré in Bloodrayne 2: Deliverance (2007)

- Bruce Greenwood in I'm Not There (2007)

- Michael A. Martinez in The Scarlet Worm (2011)

- Christopher Marrone in Abraham Lincoln vs. Zombies (2012)

- Ric Maddox in AMC's The American West (2016)

- Ethan Hawke in The Kid (2019)[75]

- Alex Roe in MGM's Billy the Kid (TV series) (2022)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman

- ^ Violence in Lincoln County, 1869–1881 A New Mexico Item by William Aloysius Keleher · 1982, p. 3

- ^ Gardner 2009, p. 28.

- ^ Gardner 2009, p. 267.

- ^ Gardner 2009, p. 293.

- ^ 1879–1979 High Plains History East Century New Mexico Book page 41

- ^ "Juanita Martinez Garrett, first wife of Pat Garrett, gets grave marker after 142 years". Las Cruces Sun News. Gannett. August 20, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2024.

- ^ Gardner 2009.

- ^ Boardman, Mark (September 23, 2021). "Remembering Juanita Garrett". True West Magazine. Retrieved April 17, 2024.

- ^ Gardner 2009, p. 94-96.

- ^ Gardner 2009, p. 101-102.

- ^ Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, pp. 62–64

- ^ Gardner 2009, p. 111.

- ^ Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, pp. 64–65

- ^ Gardner 2009, p. 115–116.

- ^ Gardner 2009, p. 279.

- ^ Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, pp. 72–75

- ^ Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, pp. 76–81

- ^ Gardner 2009, p. 128–133.

- ^ Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, pp. 93–95

- ^ Gardner 2009, p. 139–148.

- ^ "The Death Of Billy The Kid, 1881". EyeWitness to History. 2001.

- ^ "The Death Of Billy The Kid, 1881". Eyewitness to History/Ibis Communications. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ LeMay, John and Stahl, Robert J. (2020). The Man Who Invented Billy the Kid: The Authentic Life of Ash Upson. Roswell, NM: Bicep Books. pp. 127–133. ISBN 978-1-953221-91-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jon Tuska (1994). Billy the Kid, his life and legend. Greenwood Press. p. 119. ISBN 9780313285899.

- ^ Frederick Nolan (October 20, 2014). The Billy the Kid Reader. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 358. ISBN 978-0-8061-8254-4.

- ^ Stephen Tatum (January 1, 1982). Inventing Billy the Kid: Visions of the Outlaw in America, 1881-1981. University of New Mexico Press. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0-8263-0610-4.

- ^ Tuska 1994, p. 237

- ^ Adams, Ramon F. Six-Guns and Saddle Leather: A Bibliography of Books and Pamphlets on Western Outlaws and Gunman. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969 p. 244.

- ^ Pat F. Garrett's Authentic Life of Billy the Kid, edited by Maurice Garland Fulton. New York: The Macmillan Co., 1927.

- ^ Authentic Life of Billy the Kid, by Pat F. Garrett, Greatest Sheriff of the Old Southwest. Foreword by John M. Scanland, and Eye Witness Reports. Edited by J. Brussel. New York: Atomic Books, Inc. 1946.

- ^ Pat F. Garrett, The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid, With a Biographical Foreword by Jarvis P. Garrett. Albuquerque, NM; horn and Wallace Publishers, Inc., 1964.

- ^ Hough, Emerson (1907). The Story of the Outlaw-A Study of the Western Desperado. New York: The Outing Publication Company. p. 198.

- ^ Metz, Leon C (November 12, 2019). "Garrett, Patrick Floyd Jarvis". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman – pp. 152–154.

- ^ Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman – p. 151.

- ^ Metz, Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, p. 160

- ^ Recko, Corey, Murder on the White Sands: The Disappearance of Albert and Henry Fountain University of North Texas Press, 2007[ISBN missing]

- ^ Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, pp. 203–204

- ^ Gardner 2009, p. 202.

- ^ Metz, Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, pp. 216–218

- ^ Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, pp. 227–232

- ^ Gardner 2009, p. 212.

- ^ Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, pp. 236–37, 298, 301

- ^ Gardner 2009, p. 213–215.

- ^ El Paso Herald, December 16, 1901

- ^ DeMattos, Jack. Garrett and Roosevelt, College Station, TX: Creative Publishing Company, 1988. ISBN 0-932702-42-2

- ^ El Paso Herald, January 2, 1902

- ^ El Paso Evening News, May 8, 1903

- ^ DeMattos, Jack. Garrett and Roosevelt, pp. 79–88[ISBN missing]

- ^ Reproductions of these two photos can be viewed in Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, p. 196 [ISBN missing] and DeMattos, Jack. Garrett and Roosevelt, pp. 72–73.[ISBN missing]

- ^ DeMattos, Garrett and Roosevelt, pp. 109–120.[ISBN missing]

- ^ DeMattos, Garrett and Roosevelt, p. 137

- ^ Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, p. 284

- ^ DeMattos, Jack. Garrett and Roosevelt, p. 141.

- ^ Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, pp. 285–286

- ^ a b Gardner 2009, p. 229.

- ^ The Brazel quote as related by Lucero is from The New Mexico Sentinel, Santa Fe, April 23, 1939

- ^ El Paso Times, May 5, 1909.

- ^ Metz, Leon C. p. 295.

- ^ Long, Trish. "1908: Pat Garrett killed; Dies with boots on". El Paso Times. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ Boardman, Mark (January 6, 2014). "The Assassination of Pat Garrett". True West Magazine. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ Kolb, Joseph J. (May 23, 2017). "How did Billy the Kid's killer die? New doc may put to rest one of Wild West's biggest mysteries". Foxnews. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ Shirley, Glenn. Shotgun For Hire: The Story of "Deacon" Jim Miller, Killer of Pat Garrett, pp. 74–89

- ^ Metz, Leon C.Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, p. 301

- ^ Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, p. 292

- ^ Gardner 2009, p. 241-244.

- ^ New Mexico Historic Preservation Division, Dept. of Cultural Affairs. "Pat Garrett Murder Site Historical Marker".

- ^ The Historical Marker Database – Pat Garrett Murder Site

- ^ Note: Death marker coordinates: [32.366203, -106.717152]

- ^ Schurtz, Christopher, Friends of Pat Garrett

- ^ a b "Historians hope to preserve Pat Garrett murder site". Las Cruces Sun-News. December 11, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Jameson, W. C. (2016). Pat Garrett: The Man Behind the Badge. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-67036-104-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jameson, p. 16.

- ^ "Vincent D'Onofrio Taps 'Valarian's Dane DeHaan to Play Billy the Kid in Suretone Western". Deadline. July 19, 2017. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- DeMattos, Jack. "Gunfighters of the Real West: Pat Garrett." Real West, August 1982.

- DeMattos, Jack. Garrett and Roosevelt. College Station, TX: Creative Publishing Company, 1988. ISBN 0-932702-42-2

- Gardner, Mark Lee (2009). To Hell on a Fast Horse: Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett and the Epic Chase to Justice in the Old West. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 978-0-06-136827-1.

- Garrett, Pat F. The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid, the Noted Desperado of the Southwest, Whose Deeds of Daring and Blood Made His Name a Terror in New Mexico, Arizona and Northern Mexico. Santa Fe: New Mexican Printing and Publishing Co., 1882. A facsimile edition was published by Time-Life in 1981 as one of their 31 volume "Classics of Old West" leather-bound series of books. ISBN 0-8094-3581-0

- Hough, Emerson. The Story of the Outlaw. New York: Outing Publishers, 1907.

- McCubbin, Robert G. "Pat Garrett at His Prime." NOLA Quarterly, Vol. XV, No. 2, April–June 1991.

- McCubbin, Robert G. "The 100th Anniversary of Pat Garrett's Death." True West, January–February 2008.

- Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1974. ISBN 0-8061-1067-8

- Metz, Leon C. "My Search for Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid." True West, August 1983.

- Metz, Leon C. "Researching the Conspiracy That Led to the Last Days of Pat Garrett." True West, September 1983.

- O'Connor, Richard. Pat Garrett: A Biography of the Famous Marshal and the Killer of Billy the Kid. New York: Doubleday & Co., 1960.

- Rickards, Colin. "Pat Garrett Tells 'How I Killed Billy the Kid.'" Real West, April 1971.

- Shirley, Glenn. Shotgun for Hire: The Story of "Deacon" Jim Miller, Killer of Pat Garrett. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970. ISBN 0-8061-0902-5

- Weisner, Herman B. "Garrett's Death: Conspiracy or Double Cross?" True West, December 1979.

External links

[edit]- 1850 births

- 1908 deaths

- 1908 murders in the United States

- Billy the Kid

- Bison hunters

- Cowboys

- Deaths by firearm in New Mexico

- Lawmen of the American Old West

- Lincoln County Wars

- Members of the Texas Ranger Division

- New Mexico Democrats

- New Mexico sheriffs

- People from Chambers County, Alabama

- People from Claiborne Parish, Louisiana

- People from El Paso, Texas

- People from Lincoln County, New Mexico

- People from Uvalde, Texas

- People from New Mexico Territory

- Ranchers from New Mexico

- Unsolved murders in the United States