Pararhabdodon

| Pararhabdodon Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Maxillae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Neornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ornithopoda |

| Family: | †Hadrosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Lambeosaurinae |

| Tribe: | †Tsintaosaurini |

| Genus: | †Pararhabdodon Casanovas-Cladellas, Santafé-Llopis & Isidro-Llorens, 1993 |

| Type species | |

| †Pararhabdodon isonensis Casanovas-Cladellas, Santafé-Llopis & Isidro-Llorens, 1993

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Pararhabdodon (meaning "near fluted tooth" in reference to Rhabdodon) is a genus of tsintaosaurin hadrosaurid dinosaur, from the Maastrichtian-age Upper Cretaceous Tremp Group[a] of Spain. The first remains were discovered from the Sant Romà d’Abella fossil locality and assigned to the genus Rhabdodon, and later named as the distinct species Pararhabdodon isonensis in 1993. Known material includes assorted postcranial remains, mostly vertebrae, as well as maxillae from the skull. Specimens from other sites, including remains from France, a maxilla previously considered the distinct taxon Koutalisaurus kohlerorum, an additional maxilla from another locality, the material assigned to the genera Blasisaurus and Arenysaurus, and the extensive Basturs Poble bonebed have been considered at different times to belong to the species, but all of these assignments have more recently been questioned. It was one of the last non-avian dinosaurs known from the fossil record that went extinct during the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event.[1]

Initially, the material was thought to belong to a rhabdodontid dinosaur, or some other similar type of primitive iguanodontian. Later discoveries of additional material revealed its true nature as a hadrosaur. Its placement within the group remained controversial - in 1999 it was proposed it belonged to the subfamily Lambeosaurinae, making it the first known from the continent of Europe. Later studies questioned this, instead classifying it as a more primitive hadrosauroid. In 2009 evidence was put forward that it was indeed a lambeosaurine, and more specifically a close relative of Tsintaosaurus, a genus from China. This position has been repeatedly found since, and the group containing them was later named Tsintaosaurini. A different position, related to other European lambeosaurs in the group Arenysaurini, was proposed in 2020.

History and assigned material

[edit]Sant Romà d’Abella material

[edit]

Excavation of specimens that would later be used to erect Pararhabdodon began in Spring 1985, at the Sant Romà d’Abella (SRA) locality (in the Pyrenees near Isona, Lleida, Spain) of the Talarn Formation[c] in the Tremp Group.[a][2][3][4] In 1987, Casanovas-Cladellas et al. described remains of an ornithopod from Catalonia, including a cervical vertebra, some partial dorsals, a humerus, and a fragmentary scapula, as Rhabdodon sp.[5] New remains from this site, excavated in 1990,[4] brought about a reconsideration of the material, and Casanovas-Cladellas and colleagues named it as the new genus and species Pararhabdodon isonense in 1993. At the time, it was still considered to be a rhabdodont-like basal iguanodont, hence the name; isonense was in reference to Isona.[6]

Additional material from the type locality was collected in 1994 - including two maxillae, two dorsal vertebrae, a complete sacrum, two fragmentary ribs, and a partial ischium. The species name was corrected to isonensis in 1997 by Laurent et al..[7] The new material, most importantly cranial and mandibular elements (those from the skull) led to Casanovas-Cladellas' team re-classifying it as a hadrosaurid as opposed to a basal iguanodont.[8] In 1999 it was more specifically identified as a lambeosaurine hadrosaur, in a paper again by Casanovas-Cladellas et al.. This made it the first member of the subfamily from the continent, and the second valid hadrosaur, preceded by Telmatosaurus and the dubious Orthomerus.[4][9]

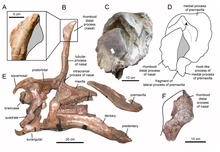

In total, known material from the type locality includes: a left and a right maxilla; five cervical, five dorsal, and one caudal vertebra; a sacrum; fragmentary rib bones; one end of the right ischium; a fragment of the left scapula, an ulna and a humerus.[3][4][10] All of this material was excavated from a 4 metres (13 ft) by 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) surface, and it is thought to have belonged to a single individual.[4] The holotype is a nearly complete caudally located cervical vertebra (a cervical vertebra located near the base of the neck), specimen number IPS SRA-1.[3][5] Another cervical, a humerus, and an ulna were designated the paratype specimens.[4] In 2020, Jesús F. Serrano and colleagues described new hindlimb material from the site, found in 2018. These are thought to belong to the holotype individual. This includes a femur, a partial tibia, a complete fibula, and a haemal arch.[11]

Referred material from other localities

[edit]

In their 1997 paper, Laurent and colleagues referred remains from the Le Bexen site of the uppermost Cretaceous of Aude, southern France, to the genus.[3][7] Prieto-Márquez and colleagues commented on this referral in a 2006 paper, although noted they had not examined the material themselves. They concluded all the specimens, excepting one fragmentary humerus, were too poorly preserved to allow proper comparison with the holotype material. As such, they disagreed with the referral. Of the humerus, they found it distinguishable from that of the SRA material, and so also not referable to the species.[3] First hand study for a 2013 re-evaluation of European lambeosaurine material supported these conclusions.[10] Laurent had, in a 2003 dissertation, referred more French lambeosaurine material to Pararhabdodon, held at the Musée des Dinosaures d’Espéraza; the referral was made as the genus was at that point the only named lambeosaurine from the continent.[10][12] Prieto-Márquez et al. (2013) used this material to establish a new taxon, Canardia garonnensis.[10]

A maxilla, specimen MCD 4919, was referred to P. isonensis in 2013. It possessed traits of the tsintaosaurin tribe which Pararhabdodon was by that point assigned to. It was referable to Pararhabdodon in particular because of the rostrocaudally broad rostrocaudal region of the maxilla, a trait unique to P. isonensis among the tribe.[10] The specimen was discovered at the Serrat del Rostiar 1 locality, part of the Conques Formation;[c] this is part of the Tremp Group[a] just like the type locality, but in a lower section of the strata, making it older. The referral to Pararhabdodon thus extended the range of the genus further within the upper Maastrichtian.[10][13] A 2019 paper questioned the referral of MCD 4919 to P. isonensis. The specimen was found to have a differing ectopterygoid shelf compared to the maxilla of the holotype, which would conflict with belonging to the same species. As the specimen was still recognized as having tsintaosaurin characteristics, the authors still considered it to likely belong to a close relative of P. isonensis.[13]

The same 2013 study also evaluated Blasisaurus canudoi, from the Blasi 1 locality of the underlying Arén Formation, and Arenysaurus ardevoli, from the Blasi 3 locality of the La Posa Formation,[d] another part of the Tremp Group.[a] Previously claimed diagnostic traits of the two taxa were shown to be found in other hadrosaurs. This left the former with two unique characteristics - both in the jugal - and a unique combination of other characteristics, and the latter with only one unique characteristic - in the frontal. As overlapping fossils were not known for the relevant areas, it could not be ruled out that they were indeed synonymous, representatives of a single species. The same re-evaluation could not rule out that this single species or either of the separated species were synonyms of Pararhabdodon isonensis, as no taxonomically informative areas of the skeleton are known from both Pararhabdodon and the other two taxa. The authors refrained from considering any of them representatives of one species pending data from more material.[10] The Pararhabdodon himdlimb described in 2020 allowed for synonymy with Arenysaurus to be ruled out, as the femurs of the two taxa were anatomically distinct.[11]

A hadrosaur mega-bonebed, later termed the Basturs Poble bonebed, was discovered in outcrops of the Conques Formation[c] during the late 1990s. The taxonomic status of this bonebed has fluctuated over time.[14] It has been debated whether the material represents a singular species or a combination of two distinct ones; but today a single, variable species is considered most likely.[14][15] It was suggested the material likely belong to Koutalisaurus, based on geographic proximity, but this reassignment was abandoned when that genus was recognized as indeterminate.[10][16] Since then, it has instead been tentatively assigned to the genus Pararhabdodon.[14] However, due to the lack of any suitable material for comparison and the lack of tsintaosaurin characteristics in the bonebed material, it has been more recently suggested that it should instead be considered indeterminate lambeosaur material.[13] The 2020 hindlimb description allowed for distinction between Pararhabdodon and the Basturs Poble material to be solidified, with the bonebed material showing inconsistent femoral anatomy with the genus.[11]

Relationship with "Koutalisaurus"

[edit]

Near the village Abella de la Conca, in the 1990s, palaeontologist Marc Boada discovered a new site in the Talarn Formation,[c] bearing dinosaur fossils.[3][13] From this site, later named Les Llaus (LL), a right dentary, specimen designation IPS SRA 27, was excavated.[3] In 1997, Casanovas-Cladellas and colleagues stated this dentary was discovered from SRA, the site where the original Pararhabdodon remains were found.[3][8] The following year, they described the specimen and referred it to P. isonensis, and again stated it was from the same stratigraphic level.[4] In 2006, the stratigraphy of the region was re-evaluated by Albert Prieto-Márquez and colleagues, and the dentary's location was corrected to the LL locality, 750 metres (2,460 ft) away from and 9 metres (30 ft) below the SRA locality. They noted that no dentary had been found at the SRA locality to compare to the LL specimen, and so they restricted P. isonensis to material known from its original locality. Additionally, they named a genus and species for IPS SRA 27, Koutalisaurus kohlerorum. One autapomorphy (unique trait) was used to diagnose the taxon as a new species: a very elongated edentulous section on the dentary, which was medially (inwardly) extended. The authors noted the possibility that future discoveries could lead to synonymization of their taxon with P. isonensis[3]

Evidence for this synonymy would later come in a 2009 study, from Prieto-Márquez alongside Jonathan R. Wagner. Material from Pararhabdodon, the holotype of Koutalisaurus, and material of the Chinese species Tsintaosaurus spinorhinus were examined and compared, and the edentulous slope previously thought unique to Koutalisaurus was found to be nearly identical in T. spinorhinus. No material had, as yet, been discovered from the SRA locality permitting comparison with Pararhabdodon. However, traits uniting P. isonensis with T. spinorhinus were found. As both taxa from the Talarn Formation[c] uniquely shared traits with the Asian genus, the authors decided to treat the two as one species, as maintaining them as provisionally separate would in their eyes be misleading to non-specialists, who would likely not distinguish that the two taxa were being kept separate to be conservative and not due to strong evidence for two hadrosaurs in the area.[17]

Prieto-Márquez returned again to the dentary in 2013, in a study alongside colleagues providing a review and investigation of hadrosaurs from all over Europe. Further preparation of the specimen in the time since his last study regarding it revealed the uniqueness of the dentary had been exaggerated significantly by reconstruction of the specimen when it was first prepared in the 1990s. The Tsintaosaurus specimens showing the similar condition were found to have been distorted from a similar process. Correcting for the inaccuracies, the Los Llaus dentary is indistinguishable from that of multiple lambeosaurines, and shares no particular connection to Tsintaosaurus. With this, their reasoning for assignment of the specimen to Pararhabdodon was voided, and the specimen is now considered a completely indeterminate lambeosaurine dentary.[10]

Description

[edit]

Pararhabdodon would have been a bipedal-quadrupedal herbivore. The holotype specimen is estimated to have been around 6 metres (20 ft) long.[3] Histological analysis indicates the individual was not fully grown, and so the species likely reached similar sizes to North American and Asian relatives such as Corythosaurus and Tsintaosaurus (around 9 metres (30 ft) long[18]). This is despite Pararhabdodon living on an island, something generally associated with insular dwarfism, a phenomenon exhibited in other European hadrosaurs; Adynomosaurus was cited as a similar example, being around the same size.[11]

Classification

[edit]

Pararhabdodon has been classified in a number of different positions within Iguanodontia since its remains were first discovered in the mid-1980s.[3][17] When the first specimens were originally discovered and described by Casanovas-Cladellas and colleagues, they were not thought to belong a new taxon at all, but merely to belong to the genus Rhabdodon, and of an uncertain species.[5] Not long after, they would be recognized of those of a unique species, and in 1993 they were given their modern name. At this point it was still thought to be a rhabdodontid or some other type of primitive iguanodont closely related to them. This was based on the characteristics of its vertebrae, as the cranial remains had not yet been found.[6] In 1994 these cranial remains would be found - two maxilla - and these would be used by the original authors to establish it as a species of hadrosaur.[8]

Casanovas-Cladellas et al. revised their position for a final time in 1999, when they published a paper arguing for a position as a primitive member of the hadrosaur subfamily Lambeosaurinae - this made it the first such species known from the continent of Europe. Characters of the skeleton supporting this viewpoint were the truncated and rounded anatomy of the articulation of the maxilla to the jugal, the truncated nature of the back of the maxilla itself, the ventral deflection of the front of the dentary (thought the only known dentary was later referred to a new species, Koutalisaurus, and later declared that of indeterminate lambeosaurine[10]), its tall neural spines, and deltopectoral crest of the humerus being distally projected.[4]

The proposal that P. isonensis was the first known European lambeosaurine was soon challenged, however, in 2001 by Jason Head, in a study re-evaluating the status of another species, Eolambia caroljonesa, as a primitive lambeosaur. Both Pararhabdodon and Eolambia were found to instead be more primitive hadrosauroids more basal than the split between Lambeosaurinae and "Hadrosaurinae" (later renamed to Saurolophinae[19]). In regards to Pararhabdodon, this was based on a rebuttal of arguments put forward in the 1999 study; the present anatomy maxilla-jugal articulation was not considered a synapomorphy in Lambeosaurinae, merely the presence of this in the jugal itself, unknown in the species, and the angular deltopectoral crest is a trait present even in primitive iguanodontians. Additionally, its tooth count was lower than those of known lambeosaurs.[20] In the 2006 re-evaluation of the genus by Albert Prieto-Márquez and colleagues, it was included in a phylogenetic analysis for the first time. This found it to be a non-hadrosaurid hadrosauroid, a similar position as had been argued by Head. The cladogram of Prieto-Márquez et al. (2006) is seen below on the left:[3]

|

Prieto-Márquez would return to the issue in 2009 along with Jonathan R. Wagner. They once again turned to the articulation between the maxilla and the jugal, finding this to link Pararhabdodon to the Asian lambeosaurine, Tsintaosaurus spinorhinus. In the 2006 phylogenetic analysis, P. isonenis had been scored as having an ancestral hadrosauroid condition for this trait, which had a strong effect on its position. Upon instead coding it for a modified version of the more advanced hadrosaurid condition, the connection between the two species to the exclusion of other lambeosaurines was supported. Multiple synapomorphies were found uniting to the two taxa, as well as identifying Pararhabdodon as a member of the subfamily as opposed to outside of Hadrosauridae.[17] This relationship was again supported in Prieto-Márquez et al. (2013), where the group containing the two genera was coined as the taxonomic tribe Tsintaosaurini; a diagnosis for the tribe was provided. Their cladogram is reproduced above, on the right.[10]

In a 2020 study describing and naming Ajnabia, Nicholas Longrich and colleagues found a novel arrangement of lambeosaur phylogeny. As opposed to European lambeosaurs being spread across different lineages, all members of the subfamily from the continent — including Pararhabdodon — were found to form one monophyletic clade, which was therein named Arenysaurini. A unique combination of primitive and derived anatomical features, as well as some unique to the group, supported them forming a clade. Tsintaosaurus was not found to be close to Pararhabdodon, instead taking a more basal position.[21]

| Hadrosauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d The geologic unit has been variously divided as the Tremp Formation, composed of several units, or the Tremp Group, composed of several formations. This article will use the Tremp Group terminology throughout for consistency.

- ^ Lower Red Unit equivalent to Talarn Formation and Gray Unit equivalent to La Posa Formation under Tremp Group nomenclature

- ^ a b c d e Equivalent to part of the "Lower Red Unit" or "Lower Red Garumnian" unit under the Tremp Formation nomenclature.

- ^ Equivalent to the "Grey Unit" or "Grey Garumnian" unit under the Tremp Formation nomenclature.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Serranoa, Jesús F.; Sellés, Albert G.; Vila, Bernat; Galobart, Àngel; Prieto-Márquez, Albert (February 2021). "The osteohistology of new remains of Pararhabdodon isonensis sheds light into the life history and paleoecology of this enigmatic European lambeosaurine dinosaur Author links open overlay panel". Cretaceous Research. 118: 104677. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104677. S2CID 225110719. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ Conti, Simone; Vila, Bernat; Sellés, Albert G.; Galobart, Àngel; Benton, Michael J.; Prieto-Márquez, Albert (2019). "The oldest lambeosaurine dinosaur from Europe: insights into the arrival of Tsintaosaurini". Cretaceous Research. 107: 104286. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.104286. hdl:1983/be876efb-979c-4237-94f9-5f8d80121f7e. S2CID 208195457.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Prieto-Marquez, A., Gaete, R., Rivas, G., Galobart, Á., and Boada, M. (2006). Hadrosauroid dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of Spain: Pararhabdodon isonensis revisited and Koutalisaurus kohlerorum, gen. et sp. nov. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26(4): 929-943.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Casanovas, M.L, Pereda-Suberbiola, X., Santafé, J.V., and Weishampel, D.B. (1999). First lambeosaurine hadrosaurid from Europe: palaeobiogeographical implications. Geological Magazine 136(2):205-211.

- ^ a b c Casanovas, M.L, Santafé, J.S., Sanz, J.L., and Buscalioni, A.D. (1987). Arcosaurios (Crocodilia, Dinosauria) del Cretácico superior de la Conca de Tremp (Lleida, España) [Archosaurs (Crocodilia, Dinosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Tremp Basin (Lleida, Spain)]. Estudios Geológicos. Volumen extraordinario Galve-Tremp:95-110. [Spanish]

- ^ a b Casanovas-Cladellas, M.L., Santafé-Llopis, J.V., and Isidro-Llorens, A. (1993). Pararhabdodon isonensis n. gen. n. sp. (Dinosauria). Estudio mofológico, radio-tomográfico y consideraciones biomecanicas [Pararhabdodon isonense n. gen. n. sp. (Dinosauria). Morphology, radio-tomographic study, and biomechanic considerations]. Paleontologia i Evolució 26-27:121-131. [Spanish]

- ^ a b Laurent, Y., LeLoeuff, J., & Buffetaut, E. (1997). Les Hadrosauridae (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) du Maastrichtien supérieur des Corbières orientales (Aude, France) [The Hadrosauridae (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) from the Upper Maastrichtian of the eastern Corbières (Aude, France)]. Revue de Paléobiologie 16:411-423. [French]

- ^ a b c Casanovas-Cladellas, M. L.; Santafé-Llopis, J. V.; Pereda-Suberbiola, X. (1997). "New remains of Pararhabdodon isonensis (Dinosauria, Hadrosauridae) and a synthesis of the assemblage of material discovered in the Upper Cretaceous of Catalonia". Second Workshop of Vertebrate Paleontology, Abstracts (Unpaginated). Espéraza-Quillan.

- ^ Casanovas-Cladellas, M. L., Santafé-Llopis, J. V., & Pereda-Suberbiola, X. (1997). Nouveaux restes de Pararhabdodon (Dinosauria, Hadrosauridae) et synthèse de l’ensemble du materiel découvert dans le Cretacé supérieur de Catalogne. In Second European Workshop of Vertebrate Paleontology, Abstracts (unpaginated).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Prieto-Márquez, A.; Dalla Vecchia, F. M.; Gaete, R.; Galobart, À. (2013). "Diversity, Relationships, and Biogeography of the Lambeosaurine Dinosaurs from the European Archipelago, with Description of the New Aralosaurin Canardia garonnensis" (PDF). PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e69835. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...869835P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069835. PMC 3724916. PMID 23922815.

- ^ a b c d Serrano, Jesús F.; Sellés, Albert G.; Vila, Bernat; Galobart, Àngel; Prieto-Márquez, Albert (2020). "The osteohistology of new remains of Pararhabdodon isonensis sheds light into the life history and paleoecology of this enigmatic European lambeosaurine dinosaur". Cretaceous Research. 118: 104677. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104677. S2CID 225110719.

- ^ Laurent, Y. (2002). Les faunes de vertébrés continentaux du Maastrichtien supérieur d'Europe: systématique et biodiversité (Doctoral dissertation, Toulouse 3).

- ^ a b c d Prieto-Márquez, Albert; Fondevilla, Víctor; Sellés, Albert G.; Wagner, Jonathan R.; Galobart; Àngel (2019). "Adynomosaurus arcanus, a new lambeosaurine dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Ibero-Armorican Island of the European Archipelago". Cretaceous Research. 96: 19–37. Bibcode:2019CrRes..96...19P. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2018.12.002. S2CID 134582286.

- ^ a b c Fondevilla, V.; Dalla Vecchia, F. M.; Gaete, R.; Galobart, À.; Moncunill-Solé, B.; Köhler, M. (2018). "Ontogeny and taxonomy of the hadrosaur (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) remains from Basturs Poble bonebed (late early Maastrichtian, Tremp Syncline, Spain)". PLOS ONE. 13 (10): e0206287. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1306287F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0206287. PMC 6209292. PMID 30379888.

- ^ Blanco, Alejandro; Prieto-Márquez, Albert; De Esteban-Trivigno, Soledad (2015). "Diversity of hadrosauroid dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous Ibero-Armorican Island (European Archipelago) assessed from dentary morphology". Cretaceous Research. 53: 447–457. Bibcode:2015CrRes..56..447B. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.04.001.

- ^ Prieto-Márquez A, Gaete R, Galobart A, Riera V. New data on European Hadrosauridae (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the latest Cretaceous of Spain. J Vertebr Paleontol. 2007;27(3): 131A.

- ^ a b c Prieto-Márquez, A.; Wagner, J.R. (2009). "Pararhabdodon isonensis and Tsintaosaurus spinorhinus: a new clade of lambeosaurine hadrosaurids from Eurasia" (PDF). Cretaceous Research. online preprint (5): 1238. Bibcode:2009CrRes..30.1238P. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2009.06.005. hdl:2152/41080. S2CID 85081036.

- ^ Benson, R.B.J.; Brussatte, M.; Xu, X. (2012). Prehistoric Life. London: Dorling Kindersley. pp. 344–345. ISBN 978-0-7566-9910-9.

- ^ Prieto-Márquez, A. (2010). "Global phylogeny of Hadrosauridae (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) using parsimony and Bayesian methods". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 159 (2): 435–502. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00617.x.

- ^ Head, Jason J. (2001). "A reanalysis of the phylogenetic position of Eolambia caroljonesa (Dinosauria, Iguanodontia)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (2): 392–396. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0392:AROTPP]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85705882.

- ^ Longrich, Nicholas R.; Suberbiola, Xabier Pereda; Pyron, R. Alexander; Jalil, Nour-Eddine (2020). "The first duckbill dinosaur (Hadrosauridae: Lambeosaurinae) from Africa and the role of oceanic dispersal in dinosaur biogeography". Cretaceous Research. 120: 104678. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12004678L. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104678. S2CID 228807024.