Palazzo del Capitaniato

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Vicenza, Province of Vicenza, Veneto, Italy |

| Part of | "City of Vicenza" part of City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i)(ii) |

| Reference | 712bis-001 |

| Inscription | 1994 (18th Session) |

| Extensions | 1996 |

| Coordinates | 45°32′50″N 11°32′45″E / 45.54722°N 11.54583°E |

The palazzo del Capitaniato, also known as loggia del Capitanio or loggia Bernarda, is a palazzo in Vicenza, northern Italy, designed by Andrea Palladio in 1565 and built in 1571 and '72. It is located on the central Piazza dei Signori, facing the Basilica Palladiana.

The palazzo is currently used by the town council, inside the Sala Bernarda. It was decorated by Lorenzo Rubini and, in the interior, with frescoes by Giovanni Antonio Fasolo. Since 1994 the palace has been part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the "City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto".

Concept and style

[edit]When one compares the Gothic arches of the Palazzo Ducale in Venice with the loggias of Palladio's Basilica, inspired by the classical language of ancient Rome (and even more if one compares the 16th-century (Cinquecento) palazzi of Vicenza with those on the Grand Canal), the Vicentines’ desire to emphasise their cultural autonomy from the architectural models of La Serenissima becomes quite clear. Nevertheless, twenty years later, when the Citizen Council commissioned for the same piazza the refacing of the official residence of the Venetian Captain (the military head in charge of the city on behalf of the Venetian Republic), it would again fall to Palladio to undertake the work, and the contest, if any, was between two extraordinary architectures rising one in front of the other.

-

Floor plan (Pereswet-Soltan, 1969)

-

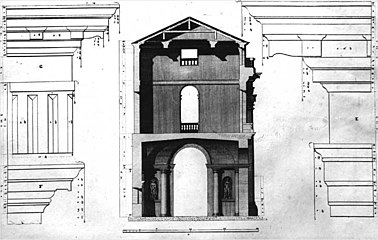

Cross section (Ottavio Bertotti Scamozzi, 1776)

It is extremely rare for any architect to have the opportunity to intervene twice in the same place, after an interval of twenty years. The young architect of the Basilica, then still under the supervision of Giovanni da Porlezza, had by now become the celebrated creator of several important buildings: churches, palaces and villas for the dominant élite of the Veneto. Palladio chose not to have the two buildings converse: against the purism of the Basilica's double-storey arcades, we find the Loggia's colossal engaged Composite columns, and while the Basilica was executed in white stone and devoid of decoration (if one ignores the design of architectural elements like the frieze, keystones and statues), the Loggia abounds in rich stucco decorations.

Both the use of the giant order and this decorative richness are twin traits peculiar to Palladio's architectural idiom in the last decade of his life. However, the chromatic contrast between the white of the stone and the red of the brick (even though desired by Palladio in the Convento della Carità in Venice) is only the product of the original surfaces’ degradation: ample remains of the light stucco which once covered the bricks are still quite visible, just below the great Composite capitals.

The Palladian loggia replaced an analogous building which had stood on the same site from the Middle Ages, and which had already been reconstructed at least twice during the Cinquecento: a covered public loggia on the ground floor and an audience hall on the upper storey. The new construction became economically viable in April 1571 and works began immediately. Palladio supplied the last drawings for the moulding templates in March 1572 and by the end of that year the building would have been roofed, since Giannantonio Fasolo could paint the lacunars of the audience hall while Lorenzo Rubini could execute the stuccoes and statues.

While the upper hall displays a flat, coffered ceiling, the ground-floor loggia has a sophisticated vault covering, certainly to better sustain the weight of the hall. The overall design is extremely sophisticated, as witnessed for example by the portals which open within the niches and follow their curvature.

The debate on whether the loggia was meant to extend to five (or seven) bays has now grown stale. It is, however, worth noting Palladio's compositional liberty in designing the façade onto the Piazza in a radically different manner to that on the Contra’ del Monte and thereby somewhat rupturing the building's unitary logic. On closer observation, however, Palladio limited himself to applying an adequate response to different situations: the piazza's broad visual frontage (also bearing in mind the dimensional constraints of the narrow façade) made necessary the powerful verticalising of the giant order; the reduced dimensions both of the building's flank and of the Contra’ del Monte itself obliged the use of a more temperate order. Moreover, the façade onto the Contra’ del Monte would be used as a sort of perennial triumphal arch, recording the victory gained by the Venetian forces over the Turks at the Battle of Lepanto in October 1571.

Gallery

[edit]-

Side view on Contrà Monte; the Basilica Palladiana is on the background

Sources

[edit]- The Loggia del Capitanio in the CISA website (source for the first revision of this article, with kind permission)

External links

[edit]- Palazzo del Capitaniato in the Palladio500 anniversary site (in Italian)

- Touristic information about the Palazzo del Capitaniato on the official Town of Vicenza website (in Italian)