Palatine tonsil

| Palatine tonsil | |

|---|---|

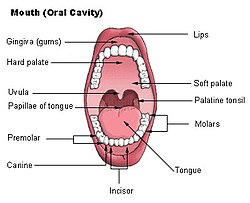

Mouth (oral cavity) | |

| |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Pharyngeal pouches |

| System | Immune system (lymphatic system) |

| Artery | Tonsillar branch of the facial artery |

| Nerve | Tonsillary branches of lesser palatine nerves |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tonsilla palatina |

| MeSH | D014066 |

| TA98 | A05.2.01.011 |

| TA2 | 2853, 5181 |

| FMA | 9610 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Palatine tonsils, commonly called the tonsils and occasionally called the faucial tonsils,[1] are tonsils located on the left and right sides at the back of the throat, which can often be seen as flesh-colored, pinkish lumps. Tonsils only present as "white lumps" if they are inflamed or infected with symptoms of exudates (pus drainage) and severe swelling.

Tonsillitis is an inflammation of the tonsils and will often, but not necessarily, cause a sore throat and fever.[2] In chronic cases, tonsillectomy may be indicated.[3]

Structure

[edit]The palatine tonsils are located in the isthmus of the fauces, between the palatoglossal arch and the palatopharyngeal arch of the soft palate.

The palatine tonsil is one of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues (MALT), located at the entrance to the upper respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts to protect the body from the entry of exogenous material through mucosal sites.[4][5] In consequence it is a site of, and potential focus for, infections, and is one of the chief immunocompetent tissues in the oropharynx. It forms part of the Waldeyer's ring, which comprises the adenoid, the paired tubal tonsils, the paired palatine tonsils and the lingual tonsils.[6] From the pharyngeal side, they are covered with a stratified squamous epithelium, whereas a fibrous capsule links them to the wall of the pharynx. Through the capsule pass trabecules that contain small blood vessels, nerves and lymphatic vessels. These trabecules divide the tonsil into lobules.

Blood supply and innervation

[edit]The nerves supplying the palatine tonsils come from the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve via the lesser palatine nerves, and from the tonsillar branches of the glossopharyngeal nerve. The glossopharyngeal nerve continues past the palatine tonsil and innervates the posterior 1/3 of the tongue to provide general and taste sensation.[6] This nerve is most likely to be damaged during a tonsillectomy, which leads to reduced or lost general sensation and taste sensation to the posterior third of the tongue.[7][8]

Blood supply is provided by tonsillar branches of five arteries: the dorsal lingual artery (of the lingual artery), ascending palatine artery (of the facial artery), tonsillar branch (of the facial artery), ascending pharyngeal artery (of the external carotid artery), and the lesser palatine artery (a branch of the descending palatine artery, itself a branch of the maxillary artery). The tonsils venous drainage is by the peritonsillar plexus, which drain into the lingual and pharyngeal veins, which in turn drain into the internal jugular vein.[6]

Tonsillar crypts

[edit]

Palatine tonsils consist of approximately 15 crypts, which result in a large internal surface. The tonsils contain four lymphoid compartments that influence immune functions, namely the reticular crypt epithelium, the extrafollicular area, the mantle zones of lymphoid follicles, and the follicular germinal centers. In human palatine tonsils, the very first part exposed to the outside environment is tonsillar epithelium.[9]

Function

[edit]Local immunity

[edit]Tonsillar (relating to palatine tonsil) B cells can mature to produce all the five major immunoglobulin (Ig, aka antibody) classes.[5] Furthermore, when incubated in vitro with either mitogens or specific antigens, they produce specific antibodies against diphtheria toxoid, poliovirus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, and the lipopolysaccharide of E. coli. Most Immunoglobulin A produced by tonsillar B cells in vitro appears to be 7S monomers, although a significant proportion may be l0S dimeric IgA.

In addition to humoral immunity elicited by tonsillar and adenoidal B cells following antigenic stimulation, there is considerable T-cell response in palatine tonsils.[5] Thus, natural infection or intranasal immunization with live, attenuated rubella virus vaccine has been reported to prime tonsillar lymphocytes much better than subcutaneous vaccination. Also, natural infection with varicella zoster virus has been found to stimulate tonsillar lymphocytes better than lymphocytes from peripheral blood.

Cytokine action

[edit]Cytokines are humoral immunomodulatory proteins or glycoproteins which control or modulate the activities of target cells, resulting in gene activation, leading to mitotic division, growth and differentiation, migration, or apoptosis. They are produced by wide range of cell types upon antigen-specific and non-antigen specific stimuli. It has been reported by many studies that the clinic outcome of many infectious, autoimmune, or malignant diseases appears to be influenced by the overall balance of production (profiles) of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, determination of cytokine profiles in tonsil study will provide key information for further in-depth analysis of the cause and underlying mechanisms of these disorders, as well as the role and possible interactions between the T- and B-lymphocytes and other immunocompetent cells.[10]

The cytokine network represents a very sophisticated and versatile regulatory system that is essential to the immune system for overcoming the various defense strategies of microorganisms. Through several studies, the Th1 and Th2 cytokines and cytokine mRNA are both detectable in tonsillar hypertrophy (or obstructive sleep apnea, OSA) and recurrent tonsillitis groups. It showed that human palatine tonsil is an active immunological organ containing a wide range of cytokine-producing cells. Both Th1 and Th2 cells are involved in the pathophysiology of TH and RT conditions. Indeed, human tonsils persistently harbor microbial antigens even when the subject is asymptomatic of ongoing infection. It could also be an effect of ontogeny of the immune system.

Clinical significance

[edit]The pathogenesis of infectious/inflammatory disease in the tonsils most likely has its basis in their anatomic location and their inherent function as organ of immunity, processing infectious material, and other antigens and then becoming, paradoxically, a focus of infection/inflammation. No single theory of pathogenesis has yet been accepted, however. Viral infection with secondary bacterial invasion may be one mechanism of the initiation of chronic disease,[11] but the effects of the environment, host factors, the widespread use of antibiotics, ecological considerations, and diet all may play a role.[12] A recent cross-sectional study revealed a high rate of prevalent virus infections in non-acutely ill patients undergoing routine tonsillectomy. However, none of the 27 detected viruses showed positive association to the tonsillar disease.[13]

In children, the tonsils are common sites of infections that may give rise to acute or chronic tonsillitis. However, it is still an open question whether tonsillar hypertrophy is also caused by a persistent infection. Tonsillectomy is one of the most common major operations performed on children. The indications for the operation have been complicated by the controversy over the benefits of removing a chronically infected tissue and the possible harm caused by eliminating an important immune inductive tissue.[14][15]

The information that is necessary to make a rational decision to resolve this controversy can be obtained by understanding the immunological potential of the normal palatine tonsils and comparing these functions with the changes that occur in the chronically diseased counterparts.

Acute tonsillitis

[edit]

Tonsillitis is the inflammation of tonsils. Acute tonsillitis is the most common manifestation of tonsillar disease. It is associated with sore throat, fever and difficulty swallowing.[16] The tonsils may appear normal sized or enlarged but are usually erythematous. Often, but not always, exudates can be seen. Not all these signs and symptoms are present in every patient.

Recurrent tonsillitis

[edit]Recurrent infection has been variably defined as from four to seven episodes of acute tonsillitis in one year, five episodes for two consecutive years or three episodes per year for 3 consecutive years.[17][18]

Tonsillar hypertrophy

[edit]Tonsillar hypertrophy is the enlargement of the tonsils, but without the history of inflammation. Obstructive tonsillar hypertrophy is currently the most common reason for tonsillectomy.[14] These patients present with varying degrees of disturbed sleep which may include symptoms of loud snoring, irregular breathing, nocturnal choking and coughing, frequent awakenings, sleep apnea, dysphagia and/or daytime hypersomnolence. These may lead to behavioral/mood changes in patients and facilitate the need for a polysomnography in order to determine the degree to which these symptoms are disrupting their sleep.[19][20]

Additional images

[edit]-

Lymphatic system

-

The mouth cavity. The cheeks have been slit transversely and the tongue pulled forward.

-

Throat after tonsillectomy

-

Anterior photograph of the oral cavity showing palatine tonsils (inflamed) and uvula.

-

Open mouth with no visible palatine tonsils.

-

Palatine tonsil

References

[edit]- ^ Merati AL, Rieder AA (August 2003). "Normal endoscopic anatomy of the pharynx and larynx". Am. J. Med. 115 Suppl 3A (3): 10S–14S. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00187-6. PMID 12928069.

- ^ Georgalas, Christos C.; Tolley, Neil S.; Narula, Professor Anthony (2014-07-22). "Tonsillitis". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2014: 0503. ISSN 1752-8526. PMC 4106232. PMID 25051184.

- ^ Weil-Olivier C, Sterkers G, François M, Garnier J, Reinert P, Cohen R (2006). "[Tonsillectomy in 2005]". Arch Pediatr. 13 (2): 168–74. doi:10.1016/j.arcped.2005.10.016. PMID 16386410.

- ^ Nave, H.; Gebert, A.; Pabst, R. (2001-11-01). "Morphology and immunology of the human palatine tonsil". Anatomy and Embryology. 204 (5): 367–373. doi:10.1007/s004290100210. PMID 11789984. S2CID 28797083.

- ^ a b c Perry, Marta; Whyte, Anthony (September 1998). "Immunology of the tonsils". Immunology Today. 19 (9): 414–421. doi:10.1016/S0167-5699(98)01307-3. PMID 9745205.

- ^ a b c Arambula, Alexandra; Brown, Jason R.; Neff, Laura (July 2021). "Anatomy and physiology of the palatine tonsils, adenoids, and lingual tonsils". World Journal of Otorhinolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 7 (3): 155–160. doi:10.1016/j.wjorl.2021.04.003. PMC 8356106. PMID 34430822.

- ^ Kim, Boo-Young; Lee, So Jeong; Yun, Ju Hyun; Bae, Jung Ho (February 2021). "Taste Dysfunction after Tonsillectomy: A Meta-analysis". Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. 130 (2): 205–210. doi:10.1177/0003489420946770. ISSN 0003-4894. PMID 32741219. S2CID 220943451.

- ^ Tomita, Hiroshi; Ohtuka, Kenji (2002-01-01). "Taste Disturbance After Tonsillectomy". Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 122 (4): 164–172. doi:10.1080/00016480260046571. ISSN 0001-6489. PMID 12132617. S2CID 25920988.

- ^ Perry, Marta E.; Jones, Marilyn M.; Mustafa, Y. (January 1988). "Structure of the Crypt Epithelium in Human Palatine Tonsils". Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 105 (sup454): 53–59. doi:10.3109/00016488809125005. ISSN 0001-6489. PMID 3223268.

- ^ Ezzeddini R, Darabi M, Ghasemi B, Jabbari Moghaddam Y, Jabbari Y, Abdollahi S, et al. (2012). "Circulating phospholipase-A2 activity in obstructive sleep apnea and recurrent tonsillitis". Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 76 (4): 471–4. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.12.026. PMID 22297210.

- ^ Faden, Howard; Callanan, Vincent; Pizzuto, Michael; Nagy, Mark; Wilby, Mark; Lamson, Daryl; Wrotniak, Brian; Juretschko, Stefan; St George, Kirsten (2016-11-01). "The ubiquity of asymptomatic respiratory viral infections in the tonsils and adenoids of children and their impact on airway obstruction". International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 90: 128–132. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.09.006. ISSN 0165-5876. PMC 7132388. PMID 27729119.

- ^ Zautner, Andreas E. (2012). "Adenotonsillar Disease". Recent Patents on Inflammation & Allergy Drug Discovery. 6 (2): 121–129. doi:10.2174/187221312800166877. PMID 22452646.

- ^ Silvoniemi, Antti; Mikola, Emilia; Ivaska, Lotta; Jeskanen, Marja; Löyttyniemi, Eliisa; Puhakka, Tuomo; Vuorinen, Tytti; Jartti, Tuomas (2020). "Intratonsillar detection of 27 distinct viruses: A cross-sectional study". Journal of Medical Virology. 92 (12): 3830–3838. doi:10.1002/jmv.26245. ISSN 1096-9071. PMC 7689766. PMID 32603480.

- ^ a b Marchica, Cinzia L.; Dahl, John P.; Raol, Nikhila (2019-10-01). "What's New with Tubes, Tonsils, and Adenoids?". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. Updates in Pediatric Otolaryngology. 52 (5): 779–794. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2019.05.002. ISSN 0030-6665. PMID 31353143. S2CID 198966664.

- ^ Morad, Anna; Sathe, Nila A.; Francis, David O.; McPheeters, Melissa L.; Chinnadurai, Sivakumar (2017-02-01). "Tonsillectomy Versus Watchful Waiting for Recurrent Throat Infection: A Systematic Review". Pediatrics. 139 (2): e20163490. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-3490. ISSN 0031-4005. PMC 5260157. PMID 28096515.

- ^ Mitchell, Ron B.; Archer, Sanford M.; Ishman, Stacey L.; Rosenfeld, Richard M.; Coles, Sarah; Finestone, Sandra A.; Friedman, Norman R.; Giordano, Terri; Hildrew, Douglas M.; Kim, Tae W.; Lloyd, Robin M. (February 2019). "Clinical Practice Guideline: Tonsillectomy in Children (Update)—Executive Summary". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 160 (2): 187–205. doi:10.1177/0194599818807917. ISSN 0194-5998. PMID 30921525. S2CID 85565202.

- ^ Burton, Martin J; Glasziou, Paul P; Chong, Lee Yee; Venekamp, Roderick P (2014-11-19). Cochrane ENT Group (ed.). "Tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy versus non-surgical treatment for chronic/recurrent acute tonsillitis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (11): CD001802. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001802.pub3. PMC 7075105. PMID 25407135.

- ^ Paradise, Jack L.; Bluestone, Charles D.; Bachman, Ruth Z.; Colborn, D. Kathleen; Bernard, Beverly S.; Taylor, Floyd H.; Rogers, Kenneth D.; Schwarzbach, Robert H.; Stool, Sylvan E.; Friday, Gilbert A.; Smith, Ida H. (1984-03-15). "Efficacy of Tonsillectomy for Recurrent Throat Infection in Severely Affected Children: Results of Parallel Randomized and Nonrandomized Clinical Trials". New England Journal of Medicine. 310 (11): 674–683. doi:10.1056/NEJM198403153101102. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 6700642.

- ^ Ali, N J; Pitson, D J; Stradling, J R (1993-03-01). "Snoring, sleep disturbance, and behaviour in 4-5 year olds". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 68 (3): 360–366. doi:10.1136/adc.68.3.360. ISSN 0003-9888. PMC 1793886. PMID 8280201.

- ^ Roland, Peter S.; Rosenfeld, Richard M.; Brooks, Lee J.; Friedman, Norman R.; Jones, Jacqueline; Kim, Tae W.; Kuhar, Siobhan; Mitchell, Ron B.; Seidman, Michael D.; Sheldon, Stephen H.; Jones, Stephanie (July 2011). "Clinical Practice Guideline: Polysomnography for Sleep-Disordered Breathing Prior to Tonsillectomy in Children". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 145 (1_suppl): S1–S15. doi:10.1177/0194599811409837. ISSN 0194-5998. PMID 21676944. S2CID 34193798.

External links

[edit]- "Anatomy diagram: 05287.011-1". Roche Lexicon - illustrated navigator. Elsevier. Archived from the original on 2013-04-22.