Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral

| Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King | |

Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, Mount Pleasant | |

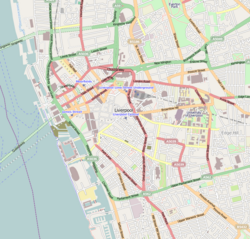

| 53°24′17″N 2°58′08″W / 53.4047°N 2.9688°W | |

| Location | Liverpool, England |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Website | liverpoolmetrocathedral.org.uk |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Sir Edwin Lutyens Sir Frederick Gibberd |

| Architectural type | Modern |

| Groundbreaking | 1962 |

| Completed | 1967 |

| Specifications | |

| Height | 84.86m[1] |

| Diameter | 59.43m |

| Administration | |

| Province | Province of Liverpool |

| Archdiocese | Archdiocese of Liverpool |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Most Rev Malcolm McMahon, OP Right Rev Bishop Thomas Williams Right Rev Bishop Thomas Neylon |

| Provost | Canon Anthony O'Brien |

| Dean | Canon Anthony O'Brien |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Dr Christopher McElroy |

| Organist(s) | Mr James Luxton (Assistant Director of Music) Mr Richard Lea (Cathedral Organist) |

Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, officially known as the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King[2] and locally nicknamed "Paddy's Wigwam",[3] is the seat of the Archbishop of Liverpool and the mother church of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Liverpool in Liverpool, England.[4][5] The Grade II* Metropolitan Cathedral is one of Liverpool's many listed buildings.

The cathedral's architect, Frederick Gibberd, was the winner of a worldwide design competition. Construction began in 1962 and was completed in 1967. Earlier designs for a cathedral were proposed in 1933 and 1953, but neither was completed.

History

[edit]Pugin's design

[edit]| External image | |

|---|---|

First design for Liverpool’s catholic cathedral, by Edward Pugin, 1853 |

During the Great Irish Famine (1845–1852) the Catholic population of Liverpool increased dramatically. About half a million Irish, who were predominantly Catholic, fled to England to escape the famine; many embarked from Liverpool to travel to North America while others remained in the city.[6] Because of the increase in the Catholic population, the co-adjutor Bishop of Liverpool, Alexander Goss (1814–1872), saw the need for a cathedral. The location he chose was the grounds of St. Edward's College on St. Domingo Road, Everton.[7]

In 1853 Goss, then bishop, awarded the commission for the building of the new cathedral to Edward Welby Pugin (1833–1875).[8] By 1856 the Lady chapel of the new cathedral had been completed. Due to financial resources being diverted to the education of Catholic children, work on the building ceased at this point and the Lady chapel – now named Our Lady Immaculate – served as parish church to the local Catholic population until its demolition in the 1980s.[9]

Lutyens' design

[edit]

Following the purchase of the 9-acre (36,000 m2) former Brownlow Hill workhouse site in 1930,[7] Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869–1944) was commissioned to provide a design which would be an appropriate response to the Giles Gilbert Scott-designed Neo-gothic Anglican cathedral then partially complete further along Hope Street.[10]

Lutyens' design was intended to create a massive structure that would have become the second-largest church in the world. It would have had the world's largest dome, with a diameter of 168 feet (51 m) compared to the 137.7 feet (42.0 m) diameter on St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City.[11] Building work based on Lutyens' design began on Whit Monday, 5 June 1933,[11] being paid for mostly by the contributions of working class Catholics of the burgeoning industrial port.[12] In 1941, the restrictions of World War II wartime and a rising cost from £3 million to £27 million[13] (£1.69 billion in 2023),[14] forced construction to stop. In 1956, work recommenced on the crypt, which was finished in 1958. Thereafter, Lutyens' design for the cathedral was considered too costly and was abandoned with only the crypt complete.[11] The restored architectural model of the Lutyens cathedral is on display at the Museum of Liverpool.[15]

Scott's reduced design

[edit]After the ambitious design by Lutyens fell through, Adrian Gilbert Scott, brother of Sir Giles Gilbert Scott (architect of the Anglican Cathedral), was commissioned in 1953 to work on a smaller cathedral design with a £4 million budget (£141 million in 2023).[14] He proposed a scaled-down version of Lutyens' building, retaining the massive dome. Scott's plans were criticised and the building did not go ahead.[7]

Gibberd's design

[edit]The present Cathedral was designed by Sir Frederick Gibberd (1908–84). Construction began in October 1962 and less than five years later, on the Feast of Pentecost 14 May 1967, the completed cathedral was consecrated.[7] Soon after its opening, it began to exhibit architectural flaws. This led the cathedral authorities to sue Frederick Gibberd for £1.3 million on five counts, the two most serious being leaks in the aluminium roof covering and defects in the mosaic tiles, which had begun to come away from the concrete ribs.[16] The design has been described by Stephen Bayley as "a thin and brittle take on an Oscar Niemeyer original in Brasilia,"[17] though Nikolaus Pevsner notes that the resemblance is only superficial.[18]

Architecture

[edit]Concept

[edit]The competition to design the cathedral was held in 1959. The requirement was first, seating for a congregation of 3,000 (later reduced to 2,000) all with direct line of sight to the altar, so they could be more involved in the celebration of the Mass; and, second, for the existing Lutyens crypt to be incorporated in the structure. Gibberd achieved these requirements by designing a circular building with the altar at its centre, and by transforming the roof of the crypt into an elevated platform, with the cathedral standing at one end.[19] The construction contract was let to Taylor Woodrow.[20]

Exterior

[edit]The cathedral is built in concrete with a Portland stone cladding and an aluminium covering to the roof.[21] Its plan is circular, having a diameter of 195 feet (59 m), with 13 chapels around its perimeter.[22] The shape of the cathedral is conical, and it is surmounted by a tower in the shape of a truncated cone.[21] The building is supported by 16 boomerang-shaped concrete trusses which are held together by two ring beams, one at the bends of the trusses and the other at their tops. Flying buttresses are attached to the trusses, giving the cathedral its tent-like appearance. Rising from the upper ring beam is a lantern tower, containing windows of stained glass, and at its peak is a crown of pinnacles.[22]

The entrance is at the top of a wide flight of steps leading up from Hope Street. Above the entrance is a large wedge-shaped structure. This acts as a bell tower, the four bells being mounted in rectangular orifices towards the top of the tower. Below these is a geometric relief sculpture, designed by William Mitchell, which includes three crosses. To the sides of the entrance doors are more reliefs in fibreglass by Mitchell, which represent the symbols of the Evangelists.[21][23] The steps which lead up to the cathedral were only completed in 2003, when a building which obstructed the stairway path was acquired and demolished by developers.[24]

A much smaller version of the cathedral, also designed by Sir Frederick Gibberd, was constructed in 1965 as a chapel for the former De La Salle College of Education, Middleton, Lancashire, a Catholic teacher-training college. The site is now occupied by Hopwood Hall College, a further education college of the Borough of Rochdale and the chapel may still be seen.[25]

Interior

[edit]

The focus of the interior is the altar which faces the main entrance. It is made of white marble from Skopje, North Macedonia, and is 10 feet (3 m) long. The floor is also of marble in grey and white designed by David Atkins. The benches, concentric with the interior, were designed by Frank Knight. Above is the tower with large areas of stained glass designed by John Piper and Patrick Reyntiens in three colours, yellow, blue and red, representing the Trinity. The glass is 1 inch (3 cm) thick, the pieces of glass being bonded with epoxy resin, in concrete frames. Around the perimeter is a series of chapels. Some of the chapels are open, some are closed by almost blank walls, and others consists of a low space under a balcony. Opposite the entrance is the Blessed Sacrament Chapel, above which is the organ. Other chapels include the Lady Chapel and the Chapel of Saint Joseph. To the right of the entrance is the Baptistry.[26]

On the altar, the candlesticks are by R. Y. Goodden and the bronze crucifix is by Elisabeth Frink. Above the altar is a baldachino designed by Gibberd as a crown-like structure composed of aluminium rods, which incorporates loudspeakers and lights. Around the interior are metal Stations of the Cross, designed by Sean Rice. Rice also designed the lectern, which includes two entwined eagles. In the Chapel of Reconciliation (formerly the Chapel of Saint Paul of the Cross), the stained glass was designed by Margaret Traherne. Stephen Foster designed, carved and painted the panelling in the Chapel of St. Joseph. The Lady Chapel contains a statue of the Virgin and Child by Robert Brumby and stained glass by Margaret Traherne. In the Blessed Sacrament Chapel is a reredos and stained glass by Ceri Richards and a small statue of the Risen Christ by Arthur Dooley. In the Chapel of Unity (formerly the Chapel of Saint Thomas Aquinas) is a bronze stoup by Virginio Ciminaghi, and a mosaic of the Pentecost by Hungarian artist Georg Mayer-Marton which was moved from the Church of the Holy Ghost, Netherton, when it was demolished in 1989. The gates of the Baptistry were designed by David Atkins.[27]

Architectural problems

[edit]The cathedral was built quickly and economically, and this led to problems with the fabric of the building, including leaks. A programme of repairs was carried out during the 1990s. The building had been faced with mosaic tiles, but these were impossible to repair and were replaced with glass-reinforced plastic, which gave it a thicker appearance. The aluminium in the lantern was replaced by stainless steel, and the slate paving of the platform was replaced with concrete flags.[22]

Cathedral crypt

[edit]

The crypt under Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral is the only part that was built according to Lutyens' design before construction stopped due to World War II; in 1962 Frederick Gibberd's design was built upon the Lutyens crypt.[11] Structurally the crypt is built of brick together with granite from quarries in Penryn, Cornwall.[28] Each year the crypt plays host to the Liverpool Beer Festival which attracts visitors, not only from all over UK but also Europe and places such as the United States and Australia.[29] The crypt also hosts examinations for students at the University of Liverpool during exam periods.[30]

Refurbishment

[edit]A £3 million refurbishment of the crypt was completed in 2009 and was officially re-opened on 1 May that year by The Duke of Gloucester.[31] The refurbishment included new east and west approaches, archive provision, rewiring and new lighting, catering facilities, a new chancel, new toilets and revamped exhibitions.[32]

Organ

[edit]

Built by J. W. Walker and Sons, the organ was completed only two days before the opening of the cathedral in 1967.[33] Made as an integral part of the new cathedral, the architect, Frederick Gibberd, saw the casework as part of his brief and so designed the striking front to the organ. Using decorative woodwork, Gibberd was inspired by the innovative use of the pipes at Coventry Cathedral and the Royal Festival Hall and so arranged the shiny zinc pipes and brass trumpets en chamade to contrast strikingly with concrete pillars which surround the organ.[34]

Specifications

[edit]The organ has four manuals, 88 speaking stops and 4565 pipes. It works by way of air pressure, controlled by an electric current and operated by the keys of the organ console; this opens and closes valves within the wind chests, allowing the pipes to speak. This type of motion is called electro-pneumatic action.[34][35]

| Organ stops | Organ pipes | |

|---|---|---|

| Great Organ | 15 | 1220 |

| Swell organ | 16 | 1159 |

| Positive Organ | 14 | 793 |

| Solo Organ | 15 | 893 |

| Accompanimental Organ | 7 | 0 |

| Pedal organ | 21 | 500 |

Gallery

[edit]-

The cathedral's four bells

-

The interior of the cathedral

-

The Great Model of Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral by Sir Edwin Lutyens presented to the Royal Academy of Arts and at the Museum of Liverpool

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ "Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King – Facts". Emporis. Archived from the original on 20 August 2004. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Metropolitan Cathedral website: The Cathedral Archived 17 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 13 August 2012

- ^ McLoughlin, Jamie (17 June 2017). "12 things you probably never knew about Paddy's Wigwam". Liverpool Echo.

- ^ "Welcome to Liverpool's Metropolitan Cathedral". Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ "The Archdiocese of Liverpool". Archdiocese of Liverpool. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ Redford & Chaloner 1976, pp. 156–157

- ^ a b c d "History of the Metropolitan Cathedral". Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral. Archived from the original on 29 January 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ^ Hammond, Lisa (June–July 2008). "No.14: Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral". www.mondoarc.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- ^ Evans, Dave (7 April 2005), St Domingo Road, Everton, Dave Evans

- ^ "Liverpool Cathedral". Visit North West. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ a b c d Edmondson, Rick. "Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral". Rick Edmondson. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ Cusack, Andrew (January 2007). "The Greatest Building Never Built". andrew cusack. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ "'Lutyens Cathedral', by Sir Edward Lutyens". Walker Art Gallery. March 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ^ a b UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "Cathedral of Dreams". Museum of Liverpool. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ Baillieu, Amanda (February 1994). "Paddy's wigwam needs repairs". The Independent. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ^ Bayley, Stephen. "Building block | 8 June 2017 | The Spectator". www.spectator.co.uk.

- ^ Pollard & Pevsner 2006, pp. 357

- ^ Pollard & Pevsner 2006, pp. 356–357

- ^ "Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral". Skyscraper News. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ a b c Historic England. "Roman Catholic Cathedral, Liverpool (1070607)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ^ a b c Pollard & Pevsner 2006, p. 357

- ^ Pollard & Pevsner 2006, p. 358

- ^ "Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral Steps". Neptune Developments Ltd. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ Proctor, Robert (23 May 2016), Building the Modern Church: Roman Catholic Church Architecture in Britain 1955 – 1975, New York: Routledge, pp. 52–53, ISBN 978-1317170860

- ^ Pollard & Pevsner 2006, pp. 358–359

- ^ Pollard & Pevsner 2006, p. 359

- ^ L'POOL CATHEDRAL (aka CATHEDRALS OF LIVERPOOL) 1940. British Pathe Ltd.

- ^ Shennan, Paddy (16 February 2010). "30 reasons to be cheerful about the Liverpool Beer Festival". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ "Exam Room Information". Archived from the original on 10 November 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Sharpe, Laura (29 April 2009). "First glimpse of refurbished Crypt at Liverpool's Metropolitan Cathedral". Liverpool Daily Post. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ "Cathedral's crypt is transformed". BBC. May 2009. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ "The Organ in the Metropolitan Cathedral, Liverpool". www.liv.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ a b "The cathedral organs". Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ Cook, James (1998). "electro pneumatic windchests". James H. Cook. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

Bibliography

- Pollard, Richard; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2006). The Buildings of England: Lancashire: Liverpool and the South-West. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10910-5.

- Redford, Arthur; Chaloner, William Henry (1976). Labour migration in England, 1800–1850. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-0636-8.

- Denizeau, Gérard (2009). Larousse des cathédrales. Paris, Éditions Larousse. ISBN 978-2-03-583961-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Gibberd, Frederick (1968). Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King, Liverpool. Architectural P. ISBN 0-85139-388-8.

External links

[edit]- Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral official website

- The cathedral that never was – [dead link] exhibition of Lutyens' cathedral model at the Walker Art Gallery

- Photographic project at padams.co.uk

| External media | |

|---|---|

| Images | |

| Video | |

- Roman Catholic cathedrals in England

- Churches in Liverpool

- Tourist attractions in Liverpool

- Grade II* listed buildings in Liverpool

- Grade II* listed cathedrals

- Buildings and structures completed in 1967

- Roman Catholic churches completed in 1967

- 20th-century Roman Catholic church buildings in the United Kingdom

- Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Liverpool

- Modern architecture in the United Kingdom

- Round churches in England