Proline-rich protein 30

| PRR30 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | PRR30, C2orf53, proline rich 30 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | MGI: 1923877; HomoloGene: 130773; GeneCards: PRR30; OMA:PRR30 - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Proline-rich protein 30 (PRR30 or C2orf53) is a protein in humans that is encoded for by the PRR30 gene.[5] PRR30 is a member in the family of Proline-rich proteins characterized by their intrinsic lack of structure. Copy number variations in the PRR30 gene have been associated with an increased risk for neurofibromatosis.

Gene

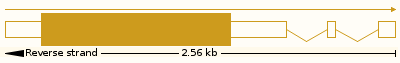

[edit]The PRR30 gene is located on the short arm of human chromosome 2 at band 2p23.3. It flanked by Prolactin regulatory element binding (PREB) and Transcription Factor 23 (TCF23). The gene has three Exons in total. PRR30 has a length of 2618 base pairs of linear DNA.[6]

Promoter Region

[edit]The PRR30 promoter directly flanks the gene and is 1162 base pairs in length.[8]

Transcript

[edit]The PRR30 mRNA transcript is 2063 base pairs in length. There are four splice sites total all of which are in the 5’ UTR. There are no known isoforms or alternative splicing of PRR30.

-

PRR30 Splice Pattern

Protein

[edit]Human protein PRR30 consists of 412 amino acid residues. It has a molecular weight of 44.7 kdal and an isoelectric point of 10.7.[9][10] It is proline rich and composed primarily of non-essential amino acids. There is a region of extreme conservation across orthologs spanning from residues 187 to 321.[11] PRR30 appears to be subcellularly localized to the cell nucleus.[12] NetNES predicts a nuclear export signal from residues 213 to 216.[13] IntAct predicts that PRR30 interacts with Human Testis Protein 37 or TEX37, Cystiene Rich Tail Protein 1 (CYSRT1), and Keratin Associated Protein 6-2 (KRTAP6-2).[14] PRR30 is predicted to undergo post-translational modifications in the form of glycosylation and phosphorylation.[15][16][17]

Structure

[edit]PRR30 is an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) and lacks any formal tertiary structure or quaternary structure.[12] I-Tasser and Phyre predict minimal coiling throughout PRR30 as a whole. In the region of high conservation, there are predicted alpha helices & beta sheets.[19][20]

Function

[edit]Unstructured proteins like PRR30 are highly variable in function.[21] Other Proline-Rich Proteins have been shown to have an affinity for binding calcium across different tissues in the human body.[22][23] COACH predicts several ligand binding domains associated with calcium across PRR30. The highest confidence predicted calcium binding domain resides in the area of greatest conservation.[24][25]

Expression

[edit]NCBI EST profiles have shown differential expression across many tissues but increased levels in the human testes and pharynx.[26]

Homology

[edit]PRR30 is exclusive to mammals but is not present in all mammals. PRR30 is highly conserved across Primates but shows loss of the gene in members of Rodents and Laurasiatheria.[27] The most distant known ortholog of PRR30 is found in S. harrisii, Tasmanian Devil. The PRR30 gene appears to be evolving relatively fast rate.[28]

Paralogs

[edit]There are no known paralogs for PRR30.[30]

Orthologs

[edit]| Genus & Species[31] | Sequence Identity[31] | Date of Divergence (MYA)[31] | Sequence Length[31] |

| Homo sapiens/Human | 100% | 0 | 412 |

| Pan paniscus | 99% | 6.4 | 412 |

| Pan troglodytes/Chimpanzee | 99% | 6.4 | 412 |

| Pongo pygmaeus/Bornean orangutan | 93% | 15.2 | 413 |

| Nomascus leucogenys | 94% | 19.43 | 412 |

| Gorilla gorilla/Western gorilla | 96% | 8.61 | 412 |

| Macaca fascicularis | 93% | 28.1 | 412 |

| Papio anubis | 93% | 28.1 | 412 |

| Macaca nemestrina | 93% | 28.1 | 412 |

| Acinonyx jubatus | 66% | 94 | 394 |

| Bos taurus | 65% | 94 | 396 |

| Bos indicus | 65% | 94 | 396 |

| Heterocephalus glaber | 57% | 88 | 373 |

| Cavia porcellus | 54% | 88 | 391 |

| Octodon degus | 61% | 88 | 402 |

| Mus musculus | 52% | 88 | 399 |

| Echinops telfairi | 61% | 102 | 313 |

| Erinaceus europaeus | 57% | 94 | 375 |

| Tupaia chinensis | 68% | 85 | 410 |

| Sorex araneus | 59% | 94 | 298 |

| Elephantulus edwardii | 51% | 102 | 286 |

| Rhinolophus sinicus | 68% | 94 | 359 |

| Miniopterus natalensis | 63% | 94 | 396 |

| Myotis brandtii | 64% | 94 | 239 |

| Sarcophilus harrisii | 57% | 160 | 376 |

- This list is not comprehensive

Clinical significance

[edit]

In recent 2015 study, copy number variation of PRR30 gene was linked to an increase risk for neurofibromatosis. 78% of the patients displaying type 1-associated cutaneous neurofibromas carried an extra copy of the PRR30 gene. No mechanism was described illuminating the correlation.[32]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000186143 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000042888 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Lamesch P, Li N, Milstein S, Fan C, Hao T, Szabo G, et al. (March 2007). "hORFeome v3.1: a resource of human open reading frames representing over 10,000 human genes". Genomics. 89 (3): 307–315. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.11.012. PMC 4647941. PMID 17207965.

- ^ 7. NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) entry on PRR30 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/148236530

- ^ "PRR30 proline rich 30 [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ^ "Genomatix: Genomatix Genome Browser". www.genomatix.de. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- ^ Brendel V, Bucher P, Nourbakhsh IR, Blaisdell BE, Karlin S (March 1992). "Methods and algorithms for statistical analysis of protein sequences". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 89 (6): 2002–2006. Bibcode:1992PNAS...89.2002B. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.6.2002. PMC 48584. PMID 1549558.

- ^ Volker Brendel, Department of Mathematics, Stanford University, Stanford CA 94305, U.S.A., modified; any errors are due to the modification.[clarification needed]

- ^ Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ (November 1994). "CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice". Nucleic Acids Research. 22 (22): 4673–4680. doi:10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. PMC 308517. PMID 7984417.

- ^ a b Rost B. "PredictProtein - Protein Sequence Analysis, Prediction of Structural and Functional Features". www.predictprotein.org. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ^ la Cour T, Kiemer L, Mølgaard A, Gupta R, Skriver K, Brunak S (June 2004). "Analysis and prediction of leucine-rich nuclear export signals". Protein Engineering, Design & Selection. 17 (6): 527–536. doi:10.1093/protein/gzh062. PMID 15314210.

- ^ Orchard S, Ammari M, Aranda B, Breuza L, Briganti L, Broackes-Carter F, et al. (January 2014). "The MIntAct project--IntAct as a common curation platform for 11 molecular interaction databases". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (Database issue): D358–D363. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1115. PMC 3965093. PMID 24234451.

- ^ Blom N, Sicheritz-Pontén T, Gupta R, Gammeltoft S, Brunak S (June 2004). "Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence". Proteomics. 4 (6): 1633–1649. doi:10.1002/pmic.200300771. PMID 15174133. S2CID 18810164.

- ^ Blom N, Gammeltoft S, Brunak S (December 1999). "Sequence and structure-based prediction of eukaryotic protein phosphorylation sites". Journal of Molecular Biology. 294 (5): 1351–1362. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1999.3310. PMID 10600390.

- ^ Gupta R, Jung E, Brunak S (2004). Prediction of N-glycosylation sites in human proteins (Report).

- ^ de Castro E. "PROSITE". prosite.expasy.org. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ^ a b Zhang Y (January 2008). "I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction". BMC Bioinformatics. 9: 40. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. PMC 2245901. PMID 18215316.

- ^ Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJ (June 2015). "The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis". Nature Protocols. 10 (6): 845–858. doi:10.1038/nprot.2015.053. PMC 5298202. PMID 25950237.

- ^ Dunker AK, Lawson JD, Brown CJ, Williams RM, Romero P, Oh JS, et al. (2001). "Intrinsically disordered protein". Journal of Molecular Graphics & Modelling. 19 (1): 26–59. doi:10.1016/s1093-3263(00)00138-8. PMID 11381529.

- ^ Wong RS, Bennick A (June 1980). "The primary structure of a salivary calcium-binding proline-rich phosphoprotein (protein C), a possible precursor of a related salivary protein A". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 255 (12): 5943–5948. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)70721-2. PMID 7380845.

- ^ Bennick A (June 1982). "Salivary proline-rich proteins". Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 45 (2): 83–99. doi:10.1007/bf00223503. PMID 6810092. S2CID 31373141.

- ^ Yang J, Roy A, Zhang Y (January 2013). "BioLiP: a semi-manually curated database for biologically relevant ligand-protein interactions". Nucleic Acids Research. 41 (Database issue): D1096–D1103. doi:10.1093/nar/gks966. PMC 3531193. PMID 23087378.

- ^ Yang J, Roy A, Zhang Y (October 2013). "Protein-ligand binding site recognition using complementary binding-specific substructure comparison and sequence profile alignment". Bioinformatics. 29 (20): 2588–2595. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btt447. PMC 3789548. PMID 23975762.

- ^ Group, Schuler. "EST Profile - Hs.136555". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Gene: PRR30 (ENSG00000186143) - Gene gain/loss tree - Homo sapiens - Ensembl genome browser 88". www.ensembl.org. Retrieved 2017-05-06.

- ^ "Ortholog Search | cegg.unige.ch Computational Evolutionary Genomics Group". www.orthodb.org. Retrieved 2017-05-06.

- ^ "Gene: PRR30 (ENSG00000186143) - Gene tree - Homo sapiens - Ensembl genome browser 88". www.ensembl.org. Retrieved 2017-05-06.

- ^ "PRR30 Gene - GeneCards | PRR30 Protein | PRR30 Antibody". GeneCards Human Gene Databas. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- ^ a b c d Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ (October 1990). "Basic local alignment search tool". Journal of Molecular Biology. 215 (3): 403–410. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1990.9999. PMID 2231712.

- ^ a b Asai A, Karnan S, Ota A, Takahashi M, Damdindorj L, Konishi Y, et al. (March 2015). "High-resolution 400K oligonucleotide array comparative genomic hybridization analysis of neurofibromatosis type 1-associated cutaneous neurofibromas". Gene. 558 (2): 220–226. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2014.12.064. PMID 25562418.