Portrait of an American Family

| Portrait of an American Family | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | July 19, 1994 | |||

| Recorded | August–December 1993 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 60:52 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer | ||||

| Marilyn Manson chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Portrait of an American Family | ||||

| ||||

Portrait of an American Family is the debut studio album by American rock band Marilyn Manson. It was released on July 19, 1994, by Nothing and Interscope Records. The group was formed in 1989 by vocalist Marilyn Manson and guitarist Daisy Berkowitz, whose names were created by combining the given name of a pop culture icon with the surname of a serial killer: a naming convention which all other band members would conform to for the next seven years. The most prominent lineup of musicians during their formative years included keyboardist Madonna Wayne Gacy, bassist Gidget Gein and drummer Sara Lee Lucas.

The band's highly visualized concerts earned them a loyal fanbase in the South Florida punk and hardcore music scene, eventually gaining the attention of Nine Inch Nails vocalist Trent Reznor, who signed them to his Nothing Records vanity label. The album was initially produced by Roli Mosimann at Criteria Studios in Miami under the title The Manson Family Album. However, the band was unhappy with his production, and this material was then re-produced and remixed in various Los Angeles recording studios by Manson and Reznor, along with assistant producers Sean Beavan and Alan Moulder. Parts of the album were re-recorded at Reznor's home studio at 10050 Cielo Drive, where members of the Manson Family infamously committed the Tate murders in 1969.

Gidget Gein was not invited to the L.A. recording sessions. He had been fired from the band in late 1993 due to his ongoing addiction to heroin. Gein was replaced by Twiggy Ramirez. Despite this, Gein is credited with performing the entirety of the bass work on the album, while the majority of Sara Lee Lucas' live drumming was replaced with electronic drum programming from Nine Inch Nails keyboardist Charlie Clouser. The record contains a wide array of cultural references; Interscope delayed its release on several occasions due to the inclusion of references to Charles Manson, and also because of objections to its controversial artwork.

Portrait of an American Family was released to limited commercial success and mostly positive reviews; in 2017, Rolling Stone deemed the album one of the greatest in the history of heavy metal music. The group embarked on several concert tours to promote the release, including appearing as an opening act on Nine Inch Nails' "Self Destruct Tour", as well as the "Portrait of an American Family Tour". "Get Your Gunn" and "Lunchbox" were issued as commercial singles, while "Dope Hat" was released as a promotional single. The record was certified gold by the Recording Industry Association of America in 2003 for shipments of over 500,000 units in the United States.

Background

[edit]Marilyn Manson and the Spooky Kids was formed in December 1989 when vocalist Marilyn Manson met guitarist Daisy Berkowitz at the Reunion Room,[4] a small nightclub in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.[5] The two were writing original compositions by the beginning of 1990, with Manson the sole lyricist and Berkowitz composing the majority of music.[4] Until 1996, the names of band members were derived from combining the first name of a pop culture icon with the surname of a serial killer.[6] The earliest incarnation of the band also included Olivia Newton Bundy on bass guitar,[7] and Zsa Zsa Speck on keyboards, along with an electronic drum machine.[8] Speck was hired by the band on a temporary basis as their original choice for keyboardist, Madonna Wayne Gacy, was unable to obtain a keyboard.[8] The original lineup was retained for two performances, the first of which took place at Churchill's Hideaway in Miami, with 20 audience members in attendance.[9] As Gacy could still not afford to purchase an instrument, he appeared on-stage at their second show – at the Reunion Room – playing with toy soldiers.[9] Speck and Bundy both exited the group sometime after this performance.[10]

The band's highly visualized concerts primarily drew from elements of shock art.[11] Their live shows routinely featured naked women nailed to crucifixes, young children locked in cages,[12] amateur pyrotechnics and sadomasochism,[11] as well as piñatas filled with butchered animal remains and experiments in reverse psychology.[N 1] These concerts quickly earned them a loyal fanbase among the South Florida punk and hardcore music scene, and were playing sold-out shows in 300-capacity nightclubs throughout Florida within six months of forming.[5] In February 1990, while working as a journalist at 25th Parallel, Manson interviewed Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails.[5] The pair remained friends afterwards, and Reznor was eventually presented with a compilation of the band's demo recordings.[13] After being impressed by the material, Reznor offered the group a spot opening for Nine Inch Nails and Meat Beat Manifesto at Club Nu in Miami on July 3, 1990.[5]

In early 1991, the group signed a record deal with Sony Music. However, Berkowitz later recalled that the president of A&R at the label, Richard Griffin, "personally rejected us within minutes, saying he liked the show and the idea but 'didn't like the singer'". They used the proceeds of the deal to fund the recording of subsequent demo tapes.[14] Bassist Gidget Gein and live drummer Sara Lee Lucas would eventually join the band, and they continued touring and releasing EPs independently for the next two years.[12] In November 1992, Reznor invited the band's vocalist to attend "strategic talks" in Los Angeles,[5] and to appear as a guitarist in a music video for the Nine Inch Nails track "Gave Up".[15] By the end of the year, Marilyn Manson and the Spooky Kids were the first act signed by Reznor's vanity label, Nothing Records,[16] shortening their name to Marilyn Manson in the beginning of 1993.[17]

Recording

[edit]"When we were finally finished, Roli had done the opposite of what I'd expected. I thought he was going to bring out some sort of darker element. But he was trying to polish all the rough edges and make us more of a rock band, a pop band, which at the time I wasn't interested in at all. I thought the record we did with him came out bland and lifeless. Trent thought the same thing so he volunteered to help us repair what had been damaged."

—Marilyn Manson discussing the aftermath of the album's initial recording sessions.[18]

Marilyn Manson held recording sessions for their debut album, then titled The Manson Family Album, in July 1993 at Criteria Studios in Miami with producer Roli Mosimann.[19] The album consisted of re-recorded versions of songs originally demoed by the group during their formative years.[12] According to Loudwire, Mosimann's original production aimed for a "sleazy, groove-laden" sound.[19] Sessions concluded several months later in the autumn.[20] At this point, Mosimann created a radio edit of "Snake Eyes and Sissies", indicating that this song was intended to be released as the lead single.[21] However, the band was unhappy with Mosimann's production, claiming it to be unrepresentative of their live performances,[18] while Manson claimed the songs sounded too polished, saying: "I thought, 'This really sucks.' So I played it for Trent, and he thought it sucked."[12]

Before reworking the album in Los Angeles, the band played shows in Florida under the name Mrs. Scabtree,[22] which consisted of members of Marilyn Manson, Amboog-a-Lard, Jack Off Jill and The Itch. Manson had produced various releases by both of the latter bands in 1993.[23] The band then travelled to the Record Plant in L.A. to remix The Manson Family Album over a seven-week period with Reznor,[19] with Manson explaining: "We spent seven weeks redoing, fixing, sometimes starting from scratch. That was our band's first experience in a real studio on a project this big. We didn't know what to expect. It was fifteen-hour days, with a team – Trent, Alan Moulder, Sean Beavan, and me – bringing out the sound."[12] Berkowitz was initially reluctant to re-record the album, saying: "I felt doing this was unnecessary, and worried it would make us look like a Nine Inch Nails/Reznor spin-off. The final result, however, is a very high-quality piece of work."[24]

Berkowitz re-recorded some of his guitar work in L.A., and the vast majority of Sara Lee Lucas' live drumming was replaced with drum programming created by Nine Inch Nails keyboardist Charlie Clouser.[19] Gidget Gein was not invited to these sessions.[19] He had been fired from the band a few days before Christmas 1993 due to his heroin addiction. Berkowitz clarified that this was "the second or third time [he was being fired], for being a junkie and not showing up. And playing really horribly live."[5] He was replaced by Jeordie White of Amboog-a-Lard, who was renamed Twiggy Ramirez.[12] Despite this, Gein is credited with performing the entirety of the bass work on the album,[12] with Ramirez credited for "base tendencies".[25] Gein later died of a heroin overdose in 2008.[26] Following this period of re-recording, The Manson Family Album was retitled to Portrait of an American Family.[19] Mosimann was listed in the liner notes as an engineer, with no mention of his original production role.[25]

Sections of the album were recorded and mixed at 10050 Cielo Drive: the address of the house where members of the Manson Family committed the Tate murders in 1969.[27] Reznor rented the property in 1992 and built a recording studio inside the residence, which he named 'Pig'—a reference to that word being written with Sharon Tate's blood on the front door of the house on the night of the massacre.[28][29] The studio is credited as 'Le Pig' in the album's liner notes.[25] Reznor denied renting the property in an attempt to have the infamy of the massacre associated with his music, and chastised Manson for doing so, saying: "I wasn't trying to create some manufactured spooky thing. Any shock value to what I was doing was about trying to sneak subversive things to a wide audience. With [Manson] ... he knew exactly what he was doing and exactly what would be shocking. Those were very conscious decisions on his part. What I was doing wasn't the same thing."[30] The house was demolished in late 1994,[31] with Reznor transporting the original "Pig" door to New Orleans, where it was installed as the entrance to his subsequent recording studio, Nothing Studios.[32]

Composition and style

[edit]

The record contains a wide array of cultural references,[25] beginning with the first track: the poem recited in "Prelude (The Family Trip)" is an adaption of a poem originally from the 1964 novel Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which later appeared during the tunnel boat ride scene from Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory.[33][34] In his autobiography, The Long Hard Road Out of Hell, Manson explained that the lyrics to the second song on the album, "Cake and Sodomy", were inspired by a trip to New York City in 1990. He said that he wrote its lyrics in a hotel room after spending several hours viewing public-access cable television and "watching Pat Robertson preach about society's evils and then ask people to call him with their credit card number. On the adjacent channel, a guy was greasing up his cock with Vaseline and asking people to call and give him their credit card number."[35] The song's intro contains several samples, including Marlon Brando in the 1972 film Last Tango in Paris saying "Go on and smile, you cunt!", and Mink Stole's character from John Waters' 1977 film Desperate Living repeatedly screaming "White trash!".[25]

"Lunchbox" was inspired by a 1972 law introduced by the Florida Legislature, which made it illegal to carry a metal lunch-box on school grounds.[36] It tells the story of a bullied child who uses a lunch-box as a defensive weapon, and proclaims that one day he will be a "big rock 'n' roll star".[37] The track incorporates elements from The Crazy World of Arthur Brown's 1968 single "Fire".[25] "Organ Grinder" makes use of various dialogue excerpts of the Child Catcher from the 1968 film Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, while "Cyclops" contains a distorted sample of the preacher from Poltergeist II: The Other Side (1986).[25][38] "Dope Hat" contains various samples of dialogue spoken by Charles Nelson Reilly – the actor who portrayed Horatio J. HooDoo – in Sid and Marty Krofft's television series Lidsville (1971–73).[25] The lyrics to "Get Your Gunn" were inspired by the murder of Dr. David Gunn, who was killed by a self-proclaimed pro-life activist.[19] Manson later described his murder as "the ultimate hypocrisy I witnessed growing up: that these people killed someone in the name of being 'pro-life'."[39] The song also features audio from the televised suicide of Pennsylvania Treasurer R. Budd Dwyer.[3][40][41]

"We were using a computer because we had a lot of samples and sequencing. While we were working on that song the Charles Manson samples from 'My Monkey' started appearing in the mix. All of a sudden we'd hear, 'Why are the children doing what they're doing? Why does a child reach up and kill his mom and dad and murder his two little sisters and then cut his throat?' And we couldn't figure what was going on. The chorus of 'Wrapped in Plastic' is, 'Come into our home/Won't you stay?' And we're in the Sharon Tate house, just me and Sean Beavan. We got scared and were like, 'We are done for the night.' We came back the next day and it was fine. The Charles Manson samples weren't even on the tape anymore. There's no real logical or technological explanation for why they appeared. It was a truly supernatural moment that freaked me out."

—Marilyn Manson discussing paranormal activity during the mixing of "Wrapped in Plastic".[42]

The title of "Wrapped in Plastic" is a reference to David Lynch's television series Twin Peaks, specifically the scene in the pilot episode where Laura Palmer's dead body is discovered wrapped in sheets of plastic. The song includes audio clips of Laura Palmer's reverse speech and screaming. [19] "Dogma" contains a sample of dialogue from John Waters' 1972 film Pink Flamingos. Although the clips from Desperate Living on "Cake and Sodomy" and "Misery Machine" are credited in the liner notes, this clip is not; Waters is additionally thanked in the album credits.[25] "Sweet Tooth" is the only song on the record for which former bassist Gidget Gein wrote both guitar and bass parts.[25]

A line of dialogue spoken at the start of "Snake Eyes and Sissies" – "Killing is killing whether done for duty, profit or fun" – is a quote taken from an interview with serial killer Richard Ramirez.[43] "My Monkey" contains numerous samples of interviews from Charles Manson;[44] several of its verses are derived from "Mechanical Man", a song from his 1970 album Lie: The Love and Terror Cult.[45] Its lyrics are credited simply to "Manson".[25] The song also contains vocals from Robert Pierce, who was six years old at the time of its recording.[46] He was the son of Rambler guitarist Richard Pierce, and was introduced to Marilyn Manson when both bands shared a rehearsal space in Florida.[47] Robert Pierce is also heard in begging for "Lunchbox".

"Misery Machine" is the thirteenth and final track on the album, and contains an interpolation of "Beep Beep" by The Playmates.[25] The title is a direct reference to the Mystery Machine from the animated television series Scooby-Doo,[19] while a phrase contained in the song, "We're gonna ride to the Abbey of Thelema", is a reference to Aleister Crowley's religion of Thelema: "Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law. Love is the law, love under will."[48] An untitled hidden track begins a few seconds after "Misery Machine", and consists of Stole in Desperate Living screaming "Go home to your mother! Doesn't she ever watch you!? Tell her this isn't some Communist daycare center! Tell your mother I hate her! Tell your mother I hate you!". After this, a telephone rings for several minutes, followed by an irate answering machine message from the mother of a Manson fan.[25]

The band's vocalist discussed his thoughts on Portrait of an American Family in retrospect with Empyrean Magazine, circa May/June 1995:

Well, the whole point of the album was that I wanted to say a lot of the things I've said in interviews. But now I feel like I fell short, like I didn't say it right. Maybe I was too vague, or maybe the songs weren't good enough, or whatever. But I wanted to address the hypocrisy of talk show America, how morals are worn as a badge to make you look good and how it's so much easier to talk about your beliefs than to live up to them. I was very much wrapped up in the concept that as kids growing up, a lot of the things that we're presented with have deeper meanings than our parents would like us to see, like Willy Wonka and the Brothers Grimm. So what I was trying to point out was that when our parents hide the truth from us, it's more damaging than if they were to expose us to things like Marilyn Manson in the first place. My point was that in this way I'm an anti-hero. I think I'll be able to say it better on the next album."[49]

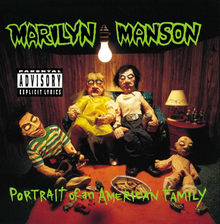

Cover and packaging

[edit]The four-member family depicted on the album cover were created by Manson using papier-mâché and human hair.[12] In The Long Hard Road Out of Hell, the vocalist said that a painting by John Wayne Gacy was originally set to feature as the cover; the same painting later appeared on the cover of Acid Bath's 1994 album When the Kite String Pops.[50] Also set to appear as part of the album's interior artwork was an image of himself as a child sitting naked on a living room couch.[16] Although the photograph was taken by his mother with no vulgar intent, and no genitalia is shown, Interscope's parent company Time Warner demanded it be removed on the grounds that it could constitute child pornography.[N 2] Manson explained the background of the image: "When I was six years old, that was when Burt Reynolds had posed for Playgirl. My mom thought it'd be funny to have me do that pose, lying on a couch. It's only sick if you have a sick mind. It was innocent."[12] Another piece of interior photography consisted of an image of a Blythe doll surrounded by Polaroid pictures of a mutilated female body, purportedly faked by Manson and several of his friends.[50]

Release and promotion

[edit]When the record was presented to Nothing's parent company Interscope in January 1994, executives at the label refused to release it unless all references to Charles Manson were removed. This included altering the band's name, and omitting the song "My Monkey".[N 3] The vocalist explained: "I think the Axl Rose/Charles Manson thing panicked them. The heat came from the name of our band. They apparently hadn't looked into it very carefully, and they had this knee-jerk reaction to what we're about."[12] Guns N' Roses had faced widespread criticism over the inclusion of "Look at Your Game, Girl" – a cover of a Charles Manson song – as a hidden track on their 1993 album "The Spaghetti Incident?".[51]

During this period, the band's management attempted to have it issued through other labels and distributors.[12] They met with Guy Oseary and Freddy DeMann from Maverick Records, Madonna's vanity label, who were initially worried that their lyrics or image included antisemitism,[N 4] although they found this was not the case. Afterward, Maverick offered the band an alternate deal.[53] Before this deal could be finalized, Interscope agreed to release the album,[12] which was issued in the United States on July 19, 1994.[19] The Honolulu Star-Bulletin reported that Members of the British Parliament tried to ban the album in the United Kingdom and called it an "outrage against society."[54] Portrait of an American Family was preceded by the release of "Get Your Gunn" as the lead single on June 9.[55] Its music video was directed by Rod Chong.[56]

Marilyn Manson performed as one of the opening acts on Nine Inch Nails' "Self Destruct Tour" throughout 1994.[30] They embarked on their first national headlining tour in December,[57] with Monster Voodoo Machine and Arab on Radar supporting.[58] The tour would be problematic, however. The band's vocalist was arrested after the tour's first date, in Jacksonville, for allegedly violating Florida's Adult Entertainment Code by simulating sex on stage while wearing a strap-on dildo.[27] He narrowly avoided arrest four nights later – on New Year's Eve in Fort Lauderdale – after Nine Inch Nails guitarist Robin Finck jumped on stage wearing a g-string and attempted to play an unspecified practical joke on the singer involving powdered sugar. Manson reacted by tearing the g-string off and placing Finck's penis in his mouth. He hid from local police in a backstage bathroom.[N 5]

This would also be drummer Sara Lee Lucas' final tour with the band. Tensions developed between him and Manson as the tour progressed and, during the second-to-last show, Manson doused Lucas' drum kit in lighter fluid and set it ablaze.[60] He was immediately replaced by Kenneth Wilson, who joined the group as Ginger Fish.[N 6] The "Lunchbox" EP was released on February 6, 1995, containing several remixes of the song created by Charlie Clouser as well as a cover of Gary Numan's "Down in the Park".[62] Richard Kern directed the music video for the track.[56] Marilyn Manson toured again in the spring of 1995, opening for Danzig alongside Korn.[63][64]

"Dope Hat" was issued as a promotional single in the summer of 1995.[65] Its music video was directed by Tom Stern,[66] and was based on the tunnel boat ride scene from Willy Wonka.[67] The band entered Reznor's Nothing Studios in New Orleans to record b-sides for the song's release as a commercial single. However, the release was cancelled, as the material recorded during these sessions was compiled into a standalone EP of cover versions, remixes and interludes titled Smells Like Children.[65] Portrait of an American Family was re-released in 2009 as a limited edition green-colored vinyl LP box set, which also contained a T-shirt emblazoned with the album cover.[68]

Critical reception and legacy

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| MusicHound Rock | |

| Rolling Stone | |

The album received mostly positive reviews. Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic said that "Beneath all the camp shock, there are signs of [Manson's] unerring eye for genuine outrage and musical talent, particularly on the trio of 'Cake and Sodomy', 'Lunchbox', and 'Dope Hat'."[73] Rolling Stone was negative, saying that the album was not the "sharply rendered cultural critique of America [Manson would] like you to think it is. Most of the record comes off like some low-budget horror movie."[72] The publication later revised its view of the record; it was included at number 68 on their 2017 list of The 100 Greatest Metal Albums of All Time.[74] Guitar World ranked the album at number thirteen in their list of the 50 Iconic Albums That Defined 1994,[75] although they also featured "Cyclops" at number 47 on their list of the 100 Worst Guitar Solos.[76] Manson himself has been dismissive of the album, ranking it in last place of the band's entire discography in a 2018 list compiled for Kerrang!.[77] Conversely, Kristy Loye of the Houston Press dubbed it the best album of the band's career, writing: "This album's impact on music at the time of release cannot really be underestimated, nor can it be accurately described in a short blurb. Like it or not, Marilyn Manson and the Spooky Kids gave rock the dark shot in the arm that was needed at the time when music had given itself completely over to the bland and self-indulgent emotional ballads of alt-rock kings like Pearl Jam. Music needed a balance of dark and light and Manson brought the darkness like few were doing at the time when suddenly metal was barely breathing."[78]

In a feature written for the twentieth anniversary of the record, Tom Breihan of Stereogum praised the album's production and quality of the band's songwriting, but said that Portrait of an American Family had aged badly, and was critical of Manson's vocals and the amount of samples used throughout. However, he went on to argue: "What still resonates about Manson isn't really his music, though 1998's Mechanical Animals still stands as a pretty incredible album. Manson was a culture-war agitator for our side: someone willing to jar and frighten the fuck out of the power structures that seemed there to keep teenagers in their place. His whole thing was a violent, overblown rejection of vast forces of oppression and control, and his tactics made him a target, both of mass-culture disdain and of superior alt-culture snark. All that was by design. He put himself out there to take those attacks. And, on some level, he's a saint for that. Simply by existing, and by moving the baseline, he made lives easier for hundreds of thousands of teenagers. That, rather than 'Cake and Sodomy', is his legacy."[33]

Commercial performance

[edit]Portrait of an American Family failed to chart upon release. Manson later complained: "Well, there was always a real chip on our shoulder that the album never really got the push from the record label that we thought it deserved. It was all about us touring our fucking asses off. We toured for two years solid, opening up for Nine Inch Nails for a year and then doing our own club tours. It was all just about perseverance."[79] It eventually peaked at number 35 on Billboard's Top Heatseekers chart, on the issue dated March 25, 1995.[80] The record was certified gold by the Recording Industry Association of America in May 2003 for shipments in excess of 500,000 units.[81] As of 2015, it has sold over 645,000 copies in the United States.[82] Despite never entering the top 100 of the UK Albums Chart,[83] in 2013 the record was certified silver by the British Phonographic Industry, indicating sales[84] in excess of 60,000 copies in that country.[85]

Track listing

[edit]All lyrics written by Marilyn Manson, except track 1 by Manson and Roald Dahl,[25] and track 12 by Marilyn Manson and Charles Manson (uncredited).[8]

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Prelude (The Family Trip)" |

| 1:20 |

| 2. | "Cake and Sodomy" | Daisy Berkowitz | 3:46 |

| 3. | "Lunchbox" |

| 4:32 |

| 4. | "Organ Grinder" |

| 4:22 |

| 5. | "Cyclops" |

| 3:32 |

| 6. | "Dope Hat" |

| 4:18 |

| 7. | "Get Your Gunn" |

| 3:18 |

| 8. | "Wrapped in Plastic" | Berkowitz | 5:35 |

| 9. | "Dogma" | Berkowitz | 3:22 |

| 10. | "Sweet Tooth" |

| 5:03 |

| 11. | "Snake Eyes and Sissies" |

| 4:07 |

| 12. | "My Monkey" | Berkowitz | 4:29 |

| 13. | "Misery Machine" ([note 1]) |

| 13:08 |

| Total length: | 60:52 | ||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14. | "Down in the Park" | Gary Numan | 5:00 |

| 15. | "Brown Bag" (Remix of "Lunchbox" by Charlie Clouser) |

| 6:19 |

| Total length: | 72:11 | ||

- "Prelude (The Family Trip)" contains an adaption of "The Rowing Song" by Roald Dahl.

- "Lunchbox" contains a vocal sample from "Fire" by The Crazy World of Arthur Brown.

- "My Monkey" contains an adaption of "Mechanical Man" by Charles Manson.

- "Misery Machine" contains an interpolation of "Beep Beep" by The Playmates.

- The record additionally features excerpts of dialogue from Last Tango in Paris, Desperate Living, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, Poltergeist II: The Other Side, Lidsville, Twin Peaks and Pink Flamingos.

- Notes

- ^ "Misery Machine" ends at 5:09, an excerpt from "Desperate Living" is played until 5:28. Telephone ringing is heard for 7:10, until an answering machine message from an irate mother is heard at 12:38.

Personnel

[edit]Credits adapted from AllMusic[87] and the liner notes of Portrait of an American Family.[25]

Marilyn Manson

- Marilyn Manson – vocals, brass, loops, production, lyrical adaption, musical composition, artwork, logo (credited as "accusations, child manipulations, backwards masking, polaroids, doll family, album design")

- Daisy Berkowitz – lead, rhythm, acoustic and wah-wah guitars, musical composition (credited as "psychoacoustical guitars")

- Gidget Gein – bass and musical composition

- Madonna Wayne Gacy – keyboards, calliope, Hammond organ, theremin, saxophone, sound effects, loops, musical composition (credited as "Hammond organ, theremin, saxophone, calliopenis, brass, babies, distorted muzette, loops, Maria, the pitiful pot pie brass section")

- Sara Lee Lucas – drums and sound effects (credited as "hitting")

Production, technical and additional personnel

- Tom Baker – mastering (at Future Disc, Los Angeles)

- Sean Beavan – brass (track 12), digital audio editing, programming, engineering, assistant producer, mixing

- Frank Callari – tour manager (for TCO Group)

- Charlie Clouser – drums (track 8), African drums, drum programming, digital audio editing

- Donovan – "tattoos"

- Mark Freegard – mixing

- Barry Goldberg – assistant engineer

- Marc Gruber – assistant engineer

- Roli Mosimann – engineering and original production

- Alan Moulder – engineering, assistant producer, mixing

- Chris Meyer – live sound

- Hope Nicholls – saxophone (track 7), background vocals (track 9)

- Robin Perine – photography

- Robert Pierce (aged 6) – vocals (tracks 3 and 12)

- Brian Pollack – assistant engineer

- Twiggy Ramirez – live bass for the "Portrait of an American Family Tour" (credited as "base tendencies")

- Trent Reznor – "bionic" guitar (track 3), brass (track 12), digital audio editing, programming, production, executive producer, mixing

- Melissa Romero (aged 19) – 'violation' on "Wrapped in Plastic"

- Brian Scheuble – assistant engineer

- Albert Sgambati – "tattoos"

- Gary Talpas – packaging

- John Tovar – management (for TCO Group)

- Chris Vrenna (credited as "Podboy") – percussion (track 6; credited as "skull" on track 10), programming, assistant engineer

- Jeff Weiss – album cover image and additional photography

- Wade Wright – "mood lighting"

- Sioux Z. – publicity (for Formula)

Charts

[edit]| Chart (1995) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Heatseekers Albums (Billboard)[88] | 35 |

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[85] | Silver | 60,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[81] | Gold | 645,000[82] |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ "In an attempt to reiterate the lesson of Willy Wonka in my own style during shows, I hung a donkey piñata over the crowd and put a stick on the edge of the stage. Then I would warn, 'Please, don't break that open. I beg you not to.' Human psychology being what it is, kids in the crowd would invariably grab the stick and smash the piñata apart, forcing everyone to suffer the consequence, which would be a shower of cow brains, chicken livers and pig intestines from [the] disemboweled donkey."[11]

- ^ "I wanted to use a photo in the booklet of me naked on a couch when I was a kid. When you hold up something to people, usually what they see in it is what's inside them in the first place. And that's what happened because the lawyers at Interscope said, 'First off, that picture's going to be considered child pornography, and not only will no stores carry the album but we're subject to legal retribution from it.' They said if a judge were to look at it, the law states that if a photograph of a minor elicits sexual excitement then it's considered child pornography. I said, 'That's exactly my point. This is a photograph that was taken by my mother, and it's extremely innocent and very normal. But if you see it as sexual, then why am I the guilty person? You're the one who's got a hard-on. Why aren't you punished?' That's still a point I'd like to make."[50]

- ^ "[After "The Spaghetti Incident?" was released, Axl Rose] started getting all that heat from Sharon Tate's sister and everyone. When our album was finished after that, we had the song 'My Monkey' on it but we had this six-year-old kid Robert Pierce singing the Charles Manson lyrics. That was the great irony of it: here's a kid that's singing a song that to him is an innocuous nursery rhyme but to everyone else is this horrible thing. After we turned the album in, I got this call from Trent and John Malm, who's Trent's manager and runs Nothing Records. And they're like 'Are you willing to put out your album without 'My Monkey' on it?' I asked, 'Why?!' And they said, 'Well, Interscope is having problems because of the shit that Axl Rose has gotten himself into. He's had to donate the proceeds of the song to the victims' families.' I said, 'Well I don't have a problem doing that. Just explain to me what's going to happen.' (The entire song wasn't Charles Manson's song. I just borrowed a few lyrics and the rest were my own.) In the end, Interscope insisted that we take the song off. I said 'No', so they told us they weren't going to put the album out at all."[46]

- ^ "While everything was in the air, Trent backed us up and stood behind us. He told us not to worry because he had an option to put out a record with any other label as part of his contract with Interscope, even though it technically owned Nothing. So we had Guy Oseary from Maverick Records down to see us and he brought Freddy DeMann, Madonna's manager. The funniest thing about those guys was the first thing they said to me after the show was 'Are you guys Jewish?' And our keyboard player said, 'Yeah, I'm Jewish, but I'm not religious. I don't practise it.' And they said 'Yeah, okay, that's cool. We gotta stick together.' We had this whole bonding thing. Then they went back to New York and our manager got a call two days later. They asked, 'We don't really have a problem with Manson's image, the tattoos, the association with the occult and Satanism. But there's something we need to know: Does Manson have any swastikas tattooed on him?' And he's like, 'No. What are you talking about?' They said, 'Well, we just wanted to check because if there's any sort of antisemitic message then it's not something we want to be involved in.' Everything I was doing was so much about sticking up for the underdog that I couldn't understand how they could misassociate what I was doing like that. It was weird. After my tattoos checked out, they actually offered us a deal. It must have lit a fire under Interscope's ass because all of a sudden Interscope came back and told us they were willing to put out the record and even pay for it. We agreed because we had always wanted Interscope from the beginning. I had faith in that label. I still do. They had a deal with Time Warner, who were the ones causing the problems."[52]

- ^ "But what happened was while we were performing, Robin [Finck], the guitarist in Nine Inch Nails, ran out on stage in a g-string with some kind of powdered confectionery item he planned to dump on me for whatever reason. In the midst of this sabotage attempt, I grabbed him and tore his g-string off and placed his limp, salty penis in my mouth and, um, teethed on it for a moment, but not long enough to really constitute a blow-job. ...I didn't have a hard-on, which should relieve me of any accusations of it being a degenerate homosexual act. Afterwards, he ran off stage sort of embarrassed and I had to flee from the cops when the show ended. They came backstage looking for me, and I hid in the bathroom where, conveniently, some drugs had been stashed. Luckily, they never issued a warrant for my arrest or prosecuted me for that particular incident."[59]

- ^ "Everybody knew that Freddy was going to be fired except for Freddy because just a week before, while he was polishing his spokes or something, we auditioned a quiet, older drummer from Las Vegas named Kenneth Wilson and asked him to join the band as Ginger Fish. He actually rode the tour bus with us one night and we told Freddy that he was just a friend of our tour manager. He bought it. We didn't want to be cruel to Freddy because we liked him as a person. We just felt obliged to make his last show with the band a memorable one. ... We sacrificed Freddy by setting his bass drum on fire, but the whole drum kit burst into flames, followed by Freddy. As Freddy escapes backstage to find a fire extinguisher we started smashing everything."[61]

References

- ^ "Marilyn Manson Biography". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 29, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ Kot, Greg (2004). "Marilyn Manson". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 513–514. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ a b Schafer, Joseph (April 8, 2015). "The 10 Best Marilyn Manson Songs". Stereogum. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved May 30, 2018.

- ^ a b Tron, Gina (April 10, 2014). "Daisy Berkowitz: Portrait of an American Ex-Marilyn Manson Member". Vice. Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Stratton, Jeff (April 15, 2004). "Manson Family Feud". New Times Broward-Palm Beach. Voice Media Group. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ Wartofsky, Alona (May 9, 1997). "Manson Family Values". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 26, 2018. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 84

- ^ a b c Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 87

- ^ a b Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 90

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 91

- ^ a b c Manson & Strauss 1998, pp. 93–94, 116

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Baker, Greg (July 20, 1994). "Manson Family Values". Miami New Times. Voice Media Group. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ Rock Revolt Staff (November 28, 2015). "Interview: SMP – Scott Mitchel Putesky (Daisy Berkowitz)". Rock Revolt Magazine. Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ Putesky, Scott (August 9, 2009). "When Marilyn Manson Left His Kids Behind". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, pp. 141–143

- ^ a b Kissell, Ted B. (February 11, 1999). "Manson: The Florida Years". Cleveland Scene. Euclid Media Group. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 122

- ^ a b Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 144

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Wiederhorn, Jon. "23 Years Ago: Marilyn Manson Issues 'Portrait of an American Family'". Loudwire. Townsquare Media. Archived from the original on May 1, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 123

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 128

- ^ Baker, Greg (February 9, 1994). "Program Notes". Miami New Times. Village Voice Media. Archived from the original on August 4, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ Baker, Greg (March 16, 1993). "Program Notes 48". Miami New Times. Village Voice Media. Archived from the original on January 12, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ Hawk, Mike (January 7, 2013). "Scott Mitchell Putesky (Daisy Berkowitz) Interview (page 1)". Blankman, Inc. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Portrait of an American Family (CD liner notes). Marilyn Manson. Interscope Records. 1994. INTD–92344.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Kaufman, Gil (October 13, 2008). "Former Marilyn Manson Bassist Gidget Gein Dead At 39". MTV. Viacom Media Networks. Archived from the original on June 29, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ a b O'Hagan, Sean (November 4, 2000). "Weekend: Sean O'Hagan meets Marilyn Manson". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 4, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Novak, Matt (October 14, 2014). "This Nine Inch Nails Video Was Shot At The Scene of An Infamous Murder". Gizmodo. Univision Communications. Archived from the original on December 11, 2017. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ^ Chua-Eoan, Howard (March 1, 2007). "The Tate-Labianca Murders, 1969". Time. Meredith Corporation. Archived from the original on March 13, 2018. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ^ a b Marchese, David (July 26, 2017). "Trent Reznor, in conversation". Vulture. New York Media. Archived from the original on May 29, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Kiefer, Peter (August 27, 2019). "To Re-create Sharon Tate's Benedict Canyon House, Quentin Tarantino Turned to an L.A. Tour Guide". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ Bozza, Anthony (October 14, 1999). "The Fragile World of Trent Reznor". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ a b Breihan, Tom (July 18, 2014). "Portrait Of An American Family Turns 20". Stereogum. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved May 30, 2018.

- ^ LaFrance, Adrienne (August 30, 2016). "Willy Wonka and Gene Wilder's Legacy". The Atlantic. Emerson Collective. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 95

- ^ Batty, Jamie (July 20, 2014). "Marilyn Manson – Portrait of an American Family | 20 Year Anniversary". HTF Magazine. Archived from the original on June 27, 2018. Retrieved May 30, 2018.

- ^ Bryant, Tom (July 15, 2014). "Six Pack: 'Fuck You' Songs | Six of the most brutal, scathing songs you'll ever wish to hear". LouderSound. Metal Hammer. Archived from the original on June 27, 2018. Retrieved May 30, 2018.

- ^ a b Strange, Jason (February 7, 2012). "A Milk Crate Full of Records: Marilyn Manson – "Portrait Of An American Family" (1994)". Music Feeds. Archived from the original on June 27, 2018. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ Marilyn Manson (May 28, 1999). "Columbine: Whose Fault Is It?" (op-ed essay). Rolling Stone. No. 815. Wenner Media LLC. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012.

- ^ Christopher, Michael (August 15, 2017). "1987 Week: Televised suicide of R. Budd Dwyer inspires morbid musical memories". Vanyaland. Archived from the original on December 12, 2017. Retrieved May 30, 2018.

- ^ Louvau, Jim (May 30, 2013). "Marilyn Manson: "I Like To Smoke and Hang Out With The Gangsta Rappers"". Phoenix New Times. Voice Media Group. Archived from the original on March 19, 2016. Retrieved May 30, 2018.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 147

- ^ Goodman, William (July 19, 2019). "The Birth of Marilyn Manson: 'Portrait of An American Family' Turns 25". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 19, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ Schonfeld, Zach (November 27, 2017). "Charles Manson's murders haunted the music world for decades". Newsweek. Archived from the original on May 30, 2018. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- ^ Garber-Paul, Elisabeth (August 9, 2016). "Charles Manson's Musical Legacy: A Murderer's Words in 9 Tracks". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 12, 2018. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- ^ a b Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 148

- ^ Cohen, Howard (August 25, 2017). "Obituary: Richard Pierce, guitarist for rock band Rambler, dies at 57 | Southern rocker who was shot and killed was a force on local music scene". Miami Herald. The McClatchy Company. Archived from the original on December 24, 2017. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Irizarry, Katy (April 9, 2018). "10 Evil Rock + Metal Songs Inspired by Aleister Crowley". Loudwire. Townsquare Media. Archived from the original on May 3, 2018. Retrieved June 6, 2018.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 151

- ^ a b c Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 150

- ^ Associated Press (December 1, 1993). "Guns N' Roses in Manson flap". Variety. Archived from the original on January 13, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 149

- ^ Epstein, Dan (July 19, 2018). "Marilyn Manson's 'Portrait of an American Family': 8 Insane Stories". Revolver. ISSN 1527-408X. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ Bueno, Greg (March 24, 1997). "Marilyn Manson Sweet To The End". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Oahu Publications Inc. (Subsidiary of Black Press Ltd.). Archived from the original on February 1, 2019. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Get Your Gunn – Marilyn Manson | Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. All Media Network. Archived from the original on July 16, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Young, Simon (January 5, 2016). "The 13 best Marilyn Manson videos". LouderSound. Metal Hammer. Archived from the original on June 26, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 154

- ^ Paul, Eric (March 11, 2015). "Satan has a new name tonight—it's Arab on Radar!". Impose. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 155

- ^ Finn, Natalie (August 5, 2007). "Marilyn Manson Accused of Bilking the Band". E!. Archived from the original on May 8, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, pp. 161–162

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Lunchbox – Marilyn Manson | Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. All Media Network. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, p. 178

- ^ Childers, Chad (May 24, 2018). "Marilyn Manson Recalls Pissing on Korn's Catering". Loudwire. Townsquare Media. Archived from the original on May 25, 2018. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ a b Manson & Strauss 1998, pp. 190–191

- ^ Ford, Chris (January 3, 2014). "10 Best Marilyn Manson Videos". Noisecreep. Townsquare Media. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ Garis, Mary Grace (October 27, 2015). "13 Creepy Music Videos Perfect For Halloween That Are Even Better Than Watching A Movie". Bustle. Archived from the original on October 23, 2017. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ "Portrait of an American Family [Limited Edition Vinyl Box set with T-Shirt]". Amazon. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Portrait of an American Family - Marilyn Manson | Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. All Media Guide. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Larkin, Colin, ed. (2007). "Marilyn Manson". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). MUZE / Omnibus Press. pp. 907–908. ISBN 978-1-84609-856-7.

- ^ Deggans, Eric (1999). "Marilyn Manson". MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Visible Ink Press. p. 714. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.

- ^ a b "Marilyn Manson: Album Guide". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media LLC. Archived from the original on April 11, 2014. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Portrait of an American Family review". AllMusic. All Media Guide (Rovi). Retrieved June 28, 2011.

- ^ Considine, J. D. (June 21, 2016). "The 100 Greatest Metal Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media LLC. Archived from the original on June 26, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Maxwell, Jackson (July 14, 2014). "Superunknown: 50 Iconic Albums That Defined 1994". Guitar World. NewBay Media. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Bienstock, Richard; Bosso, Joe; Epstein, Dan; Gill, Chris; Paul, Alan; Wiederhorn, Jon (July 14, 2014). "100 Worst Guitar Solos". Guitar World. Future US. ISSN 1045-6295. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

Originally printed in the December 2004 issue of Guitar World Magazine.

- ^ Brannigan, Paul; Manson, Marilyn (January 4, 2018). "We Asked Marilyn Manson To Rank His Albums..." Kerrang!. ISSN 0262-6624. Archived from the original on June 26, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Loye, Kristy (August 26, 2016). "All Nine Marilyn Manson Albums, Ranked". Houston Press. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, pp. 150–151

- ^ "Marilyn Manson - Portrait of an American Family - Chart History". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 27, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ a b "American album certifications – Marilyn Manson – Portrait of an American Family". Recording Industry Association of America. May 29, 2003. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ a b Macek III, J.C. (January 22, 2015). "Marilyn Manson - The Pale Emperor". PopMatters. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ "Marilyn Manson | Full Official Chart History". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ "BBC News - Beatles albums finally go platinum". BBC News. BBC. September 2, 2013. Archived from the original on April 10, 2014. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

Until July 2013, the BPI relied on a record company to request an award. Under the new system, sales figures are automatically recognised as soon as a record passes the relevant threshold.

- ^ a b "British album certifications – Marilyn Manson – Portrait of an American Family". British Phonographic Industry. July 22, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ^ Portrait of an American Family (CD liner notes). Marilyn Manson. Universal Music Group. 1997. INTD–90009.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "Portrait of an American Family - Marilyn Manson | Credits". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ "Marilyn Manson Chart History (Heatseekers Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

Bibliography

- Manson, Marilyn; Strauss, Neil (February 14, 1998). The Long Hard Road Out of Hell. New York: HarperCollins division ReganBooks. ISBN 0-06-039258-4.

The Long Hard Road Out of Hell.

- 1994 debut albums

- Albums produced by Roli Mosimann

- Albums produced by Trent Reznor

- Albums produced by Marilyn Manson

- Albums produced by Sean Beavan

- Albums produced by Alan Moulder

- Albums recorded in a home studio

- Albums recorded at Record Plant (Los Angeles)

- Interscope Records albums

- Marilyn Manson (band) albums

- Nothing Records albums

- Obscenity controversies in music