Pacific Solution

The Pacific Solution is the name given to the government of Australia's policy of transporting asylum seekers to detention centres on island nations in the Pacific Ocean, rather than allowing them to land on the Australian mainland. Initially implemented from 2001 to 2007, it had bipartisan support from the Coalition and Labor opposition at the time. The Pacific Solution consisted of three central strategies:

- Thousands of islands were excised from the Australian migration zone and Australian territory;

- The Australian Defence Force commenced Operation Relex to intercept vessels carrying asylum seekers (SIEVs);

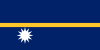

- The asylum seekers were removed to detention centres in Nauru and on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea, while their refugee status was determined.

A number of pieces of legislation enabled this policy. The policy was developed by the Howard government in response to the Tampa affair in August 2001 and the Children Overboard affair,[1] and was implemented by Immigration Minister Philip Ruddock on 28 September before the 2001 federal election of 24 November.

The policy was largely dismantled in 2008 by the first Rudd government following the election of the Labor Party; Chris Evans, the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship described it as "a cynical, costly and ultimately unsuccessful exercise".[2]

In August 2012, the succeeding Gillard government (Labor) introduced a similar policy, reopening the Nauru and Manus detention centres for offshore processing.[3]

On 19 July 2013, newly returned Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, during his short-lived second term of office, announced that "asylum seekers who come here by boat without a visa will never be settled in Australia",[4] striking a Regional Resettlement Arrangement between Australia and Papua New Guinea,[5] colloquially known as the PNG Solution, to divert all "unauthorised maritime arrivals" to mandatory detention on Manus Island with no possibility of attaining Australian residency.[6]

The Operation Sovereign Borders policy took over from the Pacific Solution after the 2013 federal election, won by the Coalition. It commenced on 18 September 2013 under the new Abbott government.[7] On 31 March 2019, Operation Sovereign Borders reported that there were no people held in the detention centre on Nauru, which had been closed, and that the Manus centre had been officially closed on 31 October 2017.[8] However, on 30 September 2019 the total number of asylum seekers still in PNG and Nauru was 562 (separate numbers were not published), being housed in alternative accommodation.[9]

Implementation (2001–2007)

[edit]

The Australian Government passed legislation on 27 September 2001, with amendments to the Commonwealth Migration Act 1958,[12] enacted by the Migration Legislation Amendment (Excision from the Migration Zone) (Consequential Provisions) Act 2001. Specifically, the new amendment to the 1958 Act allowed "offshore entry persons" to be taken to "declared countries", with Nauru and Papua New Guinea made "declared countries" under the Act.[13] The implementation of this legislation became known as the Pacific Solution[14] at the same time as or soon after the passing of the legislation (at least within a year).[13]

By redefining the area of Australian territory that could be landed upon and then legitimately used for claims of asylum (the migration zone), and by removing any intercepted people to third countries for processing, the aim was to deter future asylum seekers from making the dangerous journey by boat, once they knew that their trip would probably not end with a legitimate claim for asylum in Australia.[15]

On 28 October 2001, at his 2001 election campaign policy launch, Prime Minister John Howard said "we will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come",[16] in an effort to build support for the policy.

Asylum seekers were intercepted at sea while sailing from Indonesia and moved using Australian naval vessels. Detention centres were set up on Christmas Island, Manus Island in Papua New Guinea, and on the island nation of Nauru. Some were also accepted for processing by New Zealand. Most of the asylum seekers came from Afghanistan (largely of the Hazara ethnic group), Iraq, Iran, China, and Vietnam. The last asylum seekers to be detained on Nauru before the end of the policy had come from Sri Lanka and Myanmar.[17]

Arrivals dropped from a total of 5516 people in 2001 to one arrival in 2002 after implementation of the policy, and remained below 150 annually until 2008.[18] The removal of the Taliban from power in Afghanistan may have had some effect in this decrease,[10] as nearly six million Afghans had returned to Afghanistan since 2002, almost a quarter of the country's population at the time.[19]

Four boats were successfully returned to Indonesian waters out of the twelve Suspected Illegal Entry Vessels (SIEVs) intercepted by the Navy during Operation Relex during 2001–2002, having made 10 attempts to enforce the policy, based on judgements of whether it was safe to do so or not. Three men allegedly drowned trying to swim back to shore after returning to Indonesia.[20]

In November 2003, a boat carrying 53 passengers was successfully deterred, and in March 2004, Customs returned a boat with 15 people after interception at the Ashmore Islands.[20]

The success rate was 36 per cent of boats, or 31 per cent of asylum seekers sent back to Indonesia.[21] Details of operations from 2005 to 2008 are scant. Operation Resolute began in July 2006, run jointly by the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service and the Australian Defence Force.[22]

During the Pacific Solution period, mainland detention centres were closed at Baxter, Woomera and Curtin.[23] A lower level of boat arrivals continued throughout the Pacific Solution period, although it was reported to have peaked in 2012, since the abolition of the policy, despite worldwide asylum claim numbers remaining low by historical standards.[24] These arrivals also corresponded with increasing numbers of new refugee arrivals in Indonesia after the abandonment of the policy: 385 in 2008, 3,230 in 2009, 3,905 in 2010, 4,052 in 2011, 7,218 in 2012 and 8,332 in 2013.[25] A probable link between restrictive refugee policies and lower attempts at seeking asylum in Australia by boat have been confirmed by the UNHCR: in April 2014, UNHCR Indonesia representative Manual Jordao stated: "Word that the prospects of reaching Australia by boat from Indonesia are now virtually zero appears to have reached smugglers and would-be asylum seekers in countries of origin such as Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan and Myanmar. The numbers registering with the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) in Indonesia have dropped from about 100 a day during 2013 to about 100 a week now."[26]

The number of asylum seekers assessed as genuine refugees via the Pacific Solution process was lower than for onshore processing.[citation needed] 68 per cent of the asylum seekers were deemed genuine refugees and less than 40 per cent of asylum seekers sent to Nauru received resettlement in Australia.[citation needed] A 2006 report by the Australian Human Rights Commission showed that of the 1509 asylum seekers sent to Nauru by that time, 586 were granted Australian resettlement (39%), 360 resettled in New Zealand (24%), 19 resettled in Sweden (1.2%), 10 in Canada (<1%) and 4 in Norway (<1%). A total of 482 asylum seekers (32%) were deemed not genuine refugees and sent home.[27]

The cost of the Pacific Solution between 2001 and 2007 was at least A$1 billion.[28][29]

Amnesty International, refugee rights groups and other non-governmental organisations said that Australia was failing to meet its international obligations. The ad hoc nature in which the policy evolved was also criticised, as it resulted in people being moved to Manus Island and Nauru before facilities were ready. Poor facilities and services including intermittent electricity and fresh water, poor medical facilities and the serious mental impact of detention on people in these conditions without the certainty of being granted refugee status were also strongly criticised.[30]

Suspension

[edit]During the campaign for the 2007 parliamentary election, Australian Labor Party leader Kevin Rudd promised[citation needed] to continue the Howard government's policies of turning boats back to Indonesia and the issue of temporary protection visas.[31] Upon Kevin Rudd's 2007 election win, the Pacific Solution was abandoned, with the Nauru processing centre closed down in February 2008,[32] a move welcomed by the UN Refugee Agency.[33] The last detainees left Manus Island in 2004 and Nauru in February 2008.[34]

The Republic of Nauru was concerned about losing much-needed aid from Australia.[35] Opposition immigration spokesman Chris Ellison said the closure could suggest to people-smugglers that Australia was weakening on border protection.[36]

Re-implementation (post-2007)

[edit]

The Australian Government opened the Christmas Island Immigration Reception and Processing Centre in late 2008, and has since expanded facilities and accommodation there.[37] In the 2012–2013 financial year the Government of Australia budgeted $1.1 billion to cover the processing costs for 450 arrivals per month.[38]

From 2007 to 2010, the number of asylum seeker arrivals by boat increased substantially—from 148 in 2007 to 6555 in 2010.[39] This contributed to Rudd's ailing popularity through to 2010, when he resigned prior to a leadership spill of the Australian Labor Party to Julia Gillard; at this time Rudd said "This party and government will not be lurching to the right on the question of asylum seekers".[40]

In July 2010, Gillard showed support for the utilisation of "regional processing centres".[41] In December 2010, in the aftermath of an asylum seeker boat sinking at Christmas Island in which 48 occupants perished, Queensland Premier and ALP national president Anna Bligh called for a complete review of the government's policy on asylum seekers.[42] In May 2011, the Gillard government announced plans to address the issue of asylum seekers arriving by boat with an asylum seeker 'swap' deal for long-standing genuine refugees in Malaysia. Refugee lawyers asked the High Court to strike down the deal, arguing that the Immigration Minister did not have the power to send asylum seekers to a country that has no legal obligations to protect them.[43]

There were calls on the Australian Government to reinstate the Pacific Solution by reopening the detention centres on Nauru. Several of these came from former outspoken critics of the policy. Refugee lawyer Marion Le, who had demanded the facility be shut down in 2005, said that it was "time for Labor to bite the bullet and reopen Nauru", while human rights lawyer Julian Burnside disagreed, but conceded that "Nauru [was] certainly the less worse, but both are unacceptable."[44] This echoed the sentiment of Independent MP Andrew Wilkie who several days previously, while stopping short of calling for a return to the previous arrangement, noted that "John Howard's Pacific Solution was better."[45] The Malaysian people swap deal was deemed unlawful by the High Court.[46]

During the 2010 Australian federal election campaign Liberal Leader Tony Abbott said he would meet with the President of Nauru, Marcus Stephen, to demonstrate the Coalition's resolve to reinstate the Pacific Solution policy, should he become prime minister.[47] Prime Minister Julia Gillard announced 6 July 2010 that talks were under way to set up a regional processing centre for asylum seekers in East Timor.[48][49]

In August 2012, a government-appointed expert panel (Houston Report) recommended a number of changes to the current policy including the reintroduction of the Pacific Solution after an increase in boat people and deaths at sea. It handed down 22 recommendations, including the immediate reopening of immigration detention facilities on Manus Island and Nauru,[50] which the government implemented with bipartisan support.[51] This was expected to cost $2 billion over four years for Nauru and $900 million for Papua New Guinea.[52]

The bill to do so was passed on 16 August 2012. Asylum seekers who arrive by boat to Australia are now to be transferred to remote Pacific islands indefinitely while their claims to refugee status are being processed.[53] Amnesty International described the conditions of the Nauru detention facility as "appalling" at this time.[54]

The Government announced on 21 November 2012 that it was recommencing onshore processing with bridging visas.[55]

On 21 November 2012 Immigration Minister Chris Bowen announced the reopening the Pontville Detention Centre in Tasmania.[56] On 19 July 2013 in a joint press conference with PNG Prime Minister Peter O'Neill and Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd detailed the Regional Resettlement Arrangement between Australia and Papua New Guinea:[57]

From now on, any asylum seeker who arrives in Australia by boat will have no chance of being settled in Australia as refugees. Asylum seekers taken to Christmas Island will be sent to Manus and elsewhere in Papua New Guinea for assessment of their refugee status. If they are found to be genuine refugees they will be resettled in Papua New Guinea... If they are found not to be genuine refugees they may be repatriated to their country of origin or be sent to a safe third country other than Australia. These arrangements are contained within the Regional Resettlement Arrangement signed by myself and the Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea just now.[58]

The subsequent Department of Immigration and Citizenship press release stated: "Australia will work with PNG to expand the Manus Island Regional Processing Centre, as well as explore the construction of other regional processing centres in Papua New Guinea...The arrangements [sic] also allows for other countries (including Pacific Island states) to participate in similar arrangements in the future."[6]

The number of arrivals continued to climb, to 25,173 in the 2012–13 financial year,[39] and approximately 862 asylum seekers died trying to reach Australia between 2008 and July 2013.[59] In June 2013, Kevin Rudd toppled Gillard in another leadership spill, following weeks of polls indicating the ALP would be defeated at the next election.[60]

Operation Sovereign Borders

[edit]A new policy on boat arrival deterrence, Operation Sovereign Borders, was launched by the new Liberal–National Coalition on 18 September 2013.[61]

Papua New Guinea

[edit]The Regional Resettlement Arrangement between Australia and Papua New Guinea, colloquially known as the PNG solution, is an Australian Government policy in which any asylum seeker who comes to Australia by boat without a visa will be refused settlement in Australia, instead being settled in Papua New Guinea if they are found to be legitimate refugees. The policy includes a significant expansion of the Australian immigration detention facility on Manus Island, where refugees will be sent to be processed prior to resettlement in Papua New Guinea, and if their refugee status is found to be non-genuine, they will be either repatriated, sent to a third country other than Australia or remain in detention indefinitely. The policy was announced on 19 July 2013 by Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd and Papua New Guinean Prime Minister Peter O'Neill, effective immediately, in response to a growing number of asylum seeker boat arrivals. The then Opposition Leader Tony Abbott initially welcomed the policy, while Greens leader Christine Milne and several human rights advocate groups opposed it, with demonstrations protesting the policy held in every major Australian city after the announcement.

Announcement

[edit]In the fortnight prior to the announcement of the PNG solution, Rudd visited Indonesia for regular annual talks with Indonesian president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono where they discussed asylum seeker issues, but played down expectations of a policy announcement.[62] On 15 July, he and Immigration Minister Tony Burke visited Papua New Guinea to discuss asylum seeker policy, in light of a UN Refugee Agency report saying the Manus Island detention centre did not meet international standards.[63]

On 19 July 2013, Rudd, Burke and Papua New Guinean Prime Minister Peter O'Neill announced the policy in Brisbane.[64] Rudd declared "From now on, any asylum seeker who arrives in Australia by boat will have no chance of being settled in Australia as refugees." In his speech, he said that asylum seekers taken to Christmas Island will be sent to Manus Island or elsewhere, where their refugee status will be assessed. The announcement also outlined plans to expand the Manus Island detention facility, from 600 occupants to 3,000. All refugees found to be legitimate will be resettled in Papua New Guinea. Any asylum seekers found to be non-genuine refugees will either be repatriated, moved to a third country other than Australia if it is unsafe to be repatriated, or remain in detention indefinitely. Australia will bear the full cost of the setup of the policy, as well as provide funding for reforms of Papua New Guinea's university sector, and assistance with health, education and law and order. Rudd described the policy as "a very hard-line decision" to "combat the scourge of people smuggling".[64][65][66] The two-page Regional Resettlement Arrangement outlining the policy was signed by Rudd and O'Neill prior to the announcement.

Reception

[edit]The Australian Opposition Leader Tony Abbott initially showed support for the policy, but said it "wouldn't work under Mr Rudd".[64] The Australian Greens leader Christine Milne slammed the announcement, describing the announcement as "a day of shame".[64] It was condemned by human rights groups such as Amnesty International Australia, who wrote "Mark this day in history as the day Australia decided to turn its back on the world's most vulnerable people, closed the door and threw away the key";[67] and the UN Refugee Agency, describing the policy as potentially "harmful to the physical and psycho-social wellbeing of transferees, particularly families and children".[68] Protests of hundreds of refugee supporters were held in Melbourne,[69] Sydney,[70] Perth,[71] Brisbane and Adelaide[72] following the announcement.

On Manus Island, public opinion regarding the policy and the expansion of the detention centre was mixed.[73] Gary Juffa, governor of the Oro Province, suggested asylum seekers resettled there are likely to be met with hostility.[74]

See also

[edit]- Asylum in Australia

- Immigration to Australia

- Malaysian Solution

- Manus Regional Processing Centre

- Nauru Regional Processing Centre

- Human rights in Australia

- Human rights in Papua New Guinea

- Refugees in Indonesia

- Rwanda asylum plan

References

[edit]- ^ Philips, Janet (4 September 2012). "The 'Pacific Solution' revisited: a statistical guide to the asylum seeker caseloads on Nauru and Manus Island". Parliament of Australia. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ "Flight from Nauru ends Pacific Solution". The Sydney Morning Herald. 8 February 2008. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ^ "Govt embraces Pacific Solution measures". The Australian. 13 August 2012. Archived from the original on 13 August 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ "Kevin Rudd to send asylum seekers who arrive by boat to Papua New Guinea". The Sydney Morning Herald. 19 July 2013. Archived from the original on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ^ "Regional resettlement arrangement between Australia and Papua New Guinea" (PDF). Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ^ a b "Regional Resettlement Arrangements" (PDF). Australian Department of Immigration and Citizenship. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ^ Liberal Party of Australia & The Nationals. "The Coalition's Operation Sovereign Borders Policy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ^ "Operation Sovereign Borders monthly update: March 2019 - Australian Border Force Newsroom". newsroom.abf.gov.au. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ Australian Government. Senate. Legal And Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee (21 October 2019). "Estimates". p. 76. Archived from the original on 27 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

Proof Committee Hansard

- ^ a b "UNHCR Statistical Yearbooks 1994–2011". Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ Janet Phillips & Harriet Spinks (23 July 2013). "Boat arrivals in Australia since 1976" (PDF). Research Paper. Parliament of Australia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ "Human Rights Law Bulletin Volume 2". On 26 and 27 September 2001 the Commonwealth parliament passed migration legislation. Australian Human Rights Commission. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ a b "Chapter 10: Pacific Solution: Negotiations and Agreements (10.73)". Select Committee for an inquiry into a certain maritime incident. Report. Parliament of Australia (Report). 23 October 2002. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ "What was the 'Pacific Solution'?". the Howard Government introduced what came to be known as the 'Pacific Solution'. Parliament of Australia. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ UNHCR. "Welcomes close of Australia's Pacific Solution". Unhcr. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ "Liberals accused of trying to rewrite history . Australian Broadcasting Corp". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 21 November 2001. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ "Sri Lankans to be sent to Nauru Archived 13 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine". BBC, 15 March 2007

- ^ "Boat arrivals in Australia since 1976". Parliament of Australia. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Speech by H.E Dr. Jamaher Anwary, Minister of Refugees and Repatriation, Afghanistan, to the International Conference on the Solutions Strategy for Afghan Refugees to Support Voluntary Repatriation, Sustainable Reintegration and Assistance to Host Countries, Geneva, 2 May. 2012" (PDF). UNHCR. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ a b Jamieson, Amber (7 November 2011). "The consequences of turning boats back: SIEV towback cases". Crikey.com.au. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ^ Farr, Malcolm. "Turning back the boats? We should listen to the Navy". The Punch. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ^ "Operation RESOLUTE". Department of Defence. Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ^ "Detention centres to be scaled down". The Age. Melbourne. 11 April 2002. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- ^ "UNHCR Asylum Trends 2012" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (16 February 2016). "UNHCR – Indonesia Fact Sheet". UNHCR. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ "Asylum seekers left high and dry in Indonesia". IRIN. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ AHRC. "MIGRATION AMENDMENT (DESIGNATED UNAUTHORISED ARRIVALS) BILL 2006". AHRC. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ "a price too high: the cost of Australia's approach to asylum seekers" (PDF). Financial costs of offshore processing. A Just Australia, Oxfam Australia and Oxfam Novib. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ "Asylum seekers, the facts in figures". Crikey.com.au. 17 April 2009. Archived from the original on 13 April 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Audio of Kevin Rudd saying 'turn back the boats' in 2007". Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ "Last refugees leave Nauru". Minister for Immigration, Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship. 8 February 2008. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ "UNHCR welcomes close of Australia's Pacific Solution". Unhcr. unhcr.org. 8 February 2008. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ "UNHCR welcomes close of Australia's Pacific Solution". UNHCR welcomes the end of Australia's Pacific Solution which comes to a close today. UNHCR. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ Nauru fears gap when camps close Archived 23 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. The Age, 11 December 2007

- ^ Maley, Paul (9 February 2008). "Pacific Solution sinks quietly". The Australian. Archived from the original on 2 October 2009. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ Topsfield, Jewel (19 December 2008). "Boat influx opens Howard's 'white elephant'". The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 28 September 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- ^ Kerin, Massola and Daley (15 August 2012). "Boat arrivals a budget blowout threat". Australian Financial Review. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ^ a b Philips, Janet; Spinks, Harriet (23 July 2013). "Boat arrivals in Australia since 1976". Parliament of Australia. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ Uhlmann, Chris (10 October 2011). "Carbon tax, border protection and leadership". The 7:30 Report. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ Gillard, Julia (6 July 2010). Speech to the Lowy Institute (Speech). Sydney. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ Walker, Maley, Jamie, Paul (17 December 2010). "Christmas Island tragedy forces review of ALP's asylum stance". The Australian. Archived from the original on 6 June 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Malaysia Swap Deal For Asylum Seekers Ruled Unlawful By High Court". The Sydney Morning Herald. 31 August 2011. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ "Labor urged to revive Pacific Solution by refugee activists". The Australian. Sydney. 4 June 2011. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ Jones, Gemma (31 May 2011). "Julia Gillard's asylum seeker solution damned by independent MP Andrew Wilkie". The Telegraph. Sydney.

- ^ "Malaysian swap deal ruled unlawful". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney. 31 August 2011.

- ^ Abbott to talk to Nauru on reopening camp Archived 6 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Yuko Narushima and Kirsty Needham, The Age, 8 August 2010. Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- ^ Salna, Karlis (6 July 2010)" Gillard unveils 'East Timor solution' Archived 15 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine". The Age. Retrieved 25 December 2010

- ^ "Gillard's Timor solution: reaction". The Sydney Morning Herald. 6 July 2010. Archived from the original on 9 July 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ "3.44–3.57". Report of the Expert Panel on Asylum Seekers (Report). 13 August 2012. Archived from the original on 6 August 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ Ireland, Judith (14 August 2012). "Gillard moves swiftly on Nauru option". The Examiner. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Australian parliament to vote on Pacific Solution". Radioaustralia.net.au. 14 August 2012. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Bill Frelick, refugee program director (17 August 2012). "Australia: 'Pacific Solution' Redux". Human Rights Watch(Hrw.org). Archived from the original on 22 November 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Waters, Jeff (20 November 2012). "Amnesty International slams Nauru facility". Lateline. Archived from the original on 28 December 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "First asylum seekers arrive on Manus Island". ABC. 21 November 2012. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ "Government reopens Pontville Detention Centre". ABC News. 21 November 2012. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ REGIONAL RESETTLEMENT ARRANGEMENT BETWEEN AUSTRALIA AND PAPUA NEW GUINEA. Archived 10 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Transcript of Joint Press Conference". Commonwealth of Australia. 19 July 2013. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ^ Reilly, Alex (23 July 2013). "FactCheck: have more than 1000 asylum seekers died at sea under Labor?". The Conversation. The Conversation Media Group. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ Pearlman, Jonathan (27 June 2013). "Kevin Rudd sworn in as Australian Prime Minister". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Military reshuffle: Abbott's 'Operation Sovereign Borders'". 25 July 2013.

- ^ "Kevin Rudd arrives in Jakarta for annual talks with Indonesian president". Australia Network News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 5 July 2013. Archived from the original on 14 July 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Asylum seekers, trade on the agenda during Prime Minister Kevin Rudd's PNG visit". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 15 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Asylum seekers arriving in Australia by boat to be resettled in Papua New Guinea". ABC News. 20 July 2013. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ "Transcript of Joint Press Conference: Prime Minister, Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea, Minister for Immigration, Attorney-General". pm.gov.au. 19 July 2013. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Regional Resettlement Arrangement between Australia and Papua New Guinea" (PDF). immi.gov.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Australia passes the parcel and closes the door to desperate boat arrivals". Amnesty International Australia. 19 July 2013. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ Packham, Ben (26 July 2013). "UN refugee agency condemns Kevin Rudd's PNG asylum-seeker plan". The Australian. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ Landy, Samantha (20 July 2013). "Hundreds of refugee supporters protest Kevin Rudd's dramatic new asylum boat plan in Melbourne's CBD". Herald Sun. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Angry protesters confront Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in Sydney over asylum policy". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 22 July 2013. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Protests call for new asylum policy to be dumped". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 20 July 2013. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Hundreds rally in Brisbane and Adelaide against PNG asylum seeker plan". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 21 July 2013. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ Michael, Peter (24 July 2013). "Manus Island on high alert with malaria outbreak as asylum seeker detainees head for makeshift detention centre in PNG". Courier Mail. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Asylum seekers to receive hostile reception in PNG: local governor". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 22 July 2013. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- "Adrift In The Pacific: The Implications of Australia's Pacific Refugee Solution". Oxfam Community Aid Abroad. February 2002. Archived from the original on 14 October 2004.

- "The Pacific Solution". Refugee Action Committee. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011.

- Pagonis, Jennifer (8 February 2008). "UNHCR welcomes close of Australia's Pacific Solution". Unhcr.

This is a summary of what was said by UNHCR spokesperson Jennifer Pagonis – to whom quoted text may be attributed – at today's press briefing at the Palais des Nations in Geneva.

- Phillips, Janet; Spinks, Harriet (23 July 2013). "Boat arrivals in Australia since 1976". Parliament of Australia.

[The] background note provides a brief overview of the historical and political context surrounding boat arrivals in Australia since 1976.

- Australian migration law

- Refugees in Australia

- Internments

- 2001 in Australia

- 2001 in Nauru

- 2001 introductions

- 2001 in politics

- 2007 in Australia

- 2007 disestablishments in Australia

- 2007 in politics

- 2007 in Nauru

- 2001 in international relations

- Australia–Nauru relations

- Howard government

- Right of asylum in Australia