Otto van Veen

Otto van Veen | |

|---|---|

Otto van Veen, by Gertruida van Veen | |

| Born | 1556 |

| Died | 6 May 1629 (aged 72–73) |

| Nationality | Habsburg Netherlands |

| Known for | Painting |

Otto van Veen, also known by his Latinized names Otto Venius or Octavius Vaenius (1556 – 6 May 1629), was a painter, draughtsman, and humanist active primarily in Antwerp and Brussels in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. He is known for his paintings of religious and mythological scenes, allegories and portraits, which he produced in his large workshop in Antwerp. He further designed several emblem books, and was from 1594 or 1595 to 1598 the teacher of Rubens. His role as a classically educated humanist artist (a pictor doctus), was influential on the young Rubens, who would take on that role himself.[1] He was court painter of successive governors of the Habsburg Netherlands, including the Archdukes Albert and Isabella.[2]

Life

[edit]Van Veen was born around 1556 in Leiden, as the son of Cornelis Jansz. van Veen (1519–1591), Burgomaster of Leiden, and Geertruyd Simons van Neck (born 1530).[3][2] His father was a knight, Lord of Hogeveen, Desplasse, Vuerse, etc. and said to be descended from a natural son of John III, Duke of Brabant. He was also a doctor of law, legal advisor to the city of Leiden and representative of the County of Holland to the States General of the Habsburg Netherlands.[4] He probably was a pupil of Isaac Claesz van Swanenburg until October 1572, when the capture of Leiden by the Protestant army caused the Catholic family to move to Antwerp, and then to Liège.[5]

In Liège he became for two years a page of the Prince-Bishop of Liège. He studied there for a time under Dominicus Lampsonius and Jean Ramey. Lampsonius was a Flemish humanist, poet and painter and secretary to various Prince-Bishops of Liège. He introduced van Veen to Classicist-Humanist literature. Van Veen is documented in Rome around 1574 or 1575. He stayed there for about five years, perhaps studying with Federico Zuccari. The contemporary Flemish biographer Karel van Mander relates that van Veen subsequently worked at the courts of Rudolf II in Prague and William V of Bavaria in Munich[5] Prague and Munich were at the time the key centres of Northern Mannerist art and hosts to important Flemish artists such as Joris Hoefnagel and Bartholomeus Spranger. He returned to the Low Countries around 1580/81. he became in 1587 court painter to the governor of the Southern Netherlands, Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma at the court in Brussels until 1592. He then moved to Antwerp where he became a master in the Guild of St. Luke in 1593. He bought on 19 November 1593 a house in Antwerp for 1,000 Carolus guilders.[2]

Van Veen received numerous commissions for church decorations, including altarpieces for the Antwerp cathedral and a chapel in the city hall. He also set up a large workshop, at which Rubens trained between about 1594 to 1598. Van Veen maintained his connection with the Brussels court. When Archduke Ernest of Austria became governor in 1594, van Veen may have aided the archduke in acquiring important paintings by the likes of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder.[6] The artist later served as dean of the Guild of St. Luke of Antwerp in 1602. He was also a member of and became the dean of the Romanists in 1606. The Guild of Romanists was a society of notables and artists which was active in Antwerp from the 16th to 18th century. It was a condition of membership that the member had visited Rome.

In the 17th century, van Veen often worked for the Archdukes Albert and Isabella.[3] He also made paintings for the States General of the Dutch Republic such as the series of twelve paintings dated 1613 depicting the battles of the Romans and the Batavians,[7] based on engravings he had already published of the subject.[8]

The Archdukes Albert and Isabella appointed van Veen in 1612 as the waerdeyn ('warden') of the revived Brussels Mint. With this nomination, the Archdukes aimed to achieve two very disparate objectives. Firstly, they wanted to find a decent position for their beloved but ageing painter, and merely followed what had previously been done in 1572 when the great sculptor and medalist Jacques Jonghelinck had been made waerdeyn of the Antwerp Mint. Secondly, they needed to put at the head of the Brussels Mint a competent person, since they were then involved in launching a new series of coins as part of a general monetary reform. Van Veen appears not to have been very enthusiastic about his new appointment as he tried to resign not long after taking up his office and applied for another position in Luxembourg. This may have been linked to the difficult relaunch of the Brussels Mint. He also was unhappy with the size of the accommodation provided to him which was insufficient for his large family. It was 1616 before he moved with his family from Antwerp to Brussels to take his position. He was able to make the position of waerdeyn hereditary, which allowed his descendants starting with his son Ernest to occupy the position for a century. Van Veen gave Jacob de Bie, an Antwerp engraver, publisher and numismatist with an interest in ancient coins the position of maître particulier at the Brussels Mint. The maître particulier was in charge of buying the required quantity of precious metals and organizing the coin production.[9]

Van Veen moved to Brussels in 1615, where he died in 1629.[2]

He had two brothers who were artists: Gijsbert van Veen (1558–1630) was a respected engraver and Pieter was an amateur painter.[5] He was the uncle of three pastellists, Pieter's children, Apollonia, Symon, and Jacobus.[10] His daughter Gertruida by his wife Maria Loets (Loots or Loos) also became a painter.[11]

The early artist biographer Arnold Houbraken writing almost a century after Otto van Veen's death, considered van Veen to be the most impressive artist of his day and put his portrait on the title page of his three volume De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen, which contained the biographies of famous Flemish and Dutch artists.[12]

Emblem books

[edit]Van Veen was involved in the publication of Emblem books, including Quinti Horatii Flacci emblemata (1607), Amorum emblemata (1608), the Amoris divini emblemata (1615) and the Emblemata sive symbola (1624). In these works, van Veen's skills as an artist and learned humanist are on display. These works were also influential on the further development of the genre of emblem books.[13]

Quinti Horatii Flacci Emblemata

[edit]

His Quinti Horatii Flacci Emblemata was first published in 1607 in Antwerp by publisher Hieronymus Verdussen. It constituted a significant development in the design and conceptualization of emblem books as well as the optimization of their didactic impact. By transposing the works of the Roman poet Horace into innovative images through prints of a high technical quality the work could be used for philosophical and moral meditation.[14] Two separate editions were printed in the first year of publication. The first one contained only text fragments by Horace and other authors from Antiquity, primarily in Latin (mainly Horace) with a facing-page allegorical engraving. In the second edition, published by the same Antwerp publisher Hieronymus Verdussen, the Latin texts were accompanied by Dutch and French quatrains, and the collection of texts and pictures started to look more like traditional emblems. In the third edition of 1612 Spanish and Italian verses were added. The book was the product of the collaboration of many artists, engravers, printers, classical scholars and van Veen.[13]

The full page illustrations were of very high quality and positioned on the recto of every page opening, with the letterpress opposite each illustration on the verso. The first edition had verses in Dutch and French below the Latin quotes (drawn largely from Horace, but also other sources).[15] The Quinti Horatii Flacci Emblemata was circulated widely during the 17th and 18th centuries and was copied and pirated in France, Spain, Italy and England. The book was even used for the instruction of a future king in France as well as a pictorial-source book for the decoration of interiors.[13]

Amorum emblemata

[edit]The Amorum emblemata was published in 1608 in Antwerp by Hieronymus Verdussen in three different polyglot versions: one with Latin, Dutch and French, one with Latin, Italian and French and one in Latin, English and Italian. The Amorum emblemata pictures 124 putti, enacting mottoes of, and quotations by, lyricists, philosophers and ancient writers on the powers of Love. Rubens' brother Philip Rubens, who was a classical scholar, wrote the foreword to this book in Latin.[16]

Van Veen's book of love emblems was following a trend which was launched in Amsterdam in 1601 with the publication of Jacob de Gheyn II's Quaeris quid sit Amor, which contained 24 love emblems produced with accompanying Dutch-language verses by Daniël Heinsius. Van Veen's Amorum emblemata is wider in scope with its 124 emblems. The maxims regarding love which accompany and interpret the pictures are for the most part taken from Ovid. Aimed at young people, the emblems depict love as an overpowering drive which should be obeyed to gain happiness.[17] The Amorum emblemata became in the 17th century one of the most influential books of its time, not only as a model for other Flemish/Dutch and foreign emblem books, but also as a source of inspiration for many artists in other fields.[18]

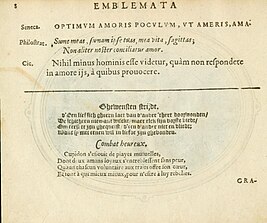

One of the emblems is entitled in Dutch Ghewensten Strijdt (Desired Combat) and in French Combat Heureux (Happy Combat). It depicts two putti holding bows who have shot each other with arrows. The accompanying motto in Dutch reads: d’Een lief sich gheern laet van d’ander ’t hert doorwonden/De schichten niemant wijckt, maer elck sijn borste biedt/Om eerst te zijn ghequetst, d’een d’ander niet en vliedt:Want sy met eenen wil in liefde zijn ghebonden. In English translation: "The one lover gladly lets the other one pierce its heart, neither dodges the arrows, but rather offers its chest to be the first one to be wounded, neither flees the other because they are bound in love in one desire". Further quotations by Seneca the Elder, Philostratus and Cicero, printed above the Dutch and French mottoes, address a similar theme on the same page.[19]

Amoris divini emblemata

[edit]

The Amoris divini emblemata was published in 1615 in Antwerp by Martinus Nutius III and Jan van Meurs. Less popular than the previous emblem books, a second impression of Amoris divini emblemata did not appear until 1660 In his address to the reader of the book, van Veen relates how the archduchess Isabella had suggested that his earlier love emblems (Amorum emblemata, 1608) might be reworked 'in a spiritual and divine sense' since 'the effects of divine and human love are, as to the loved object, nearly equal.' The two books look very alike. Formally, the emblems are very much alike in structure: on the left-hand page, first a Latin motto, then a group of quotations in Latin, and finally verses in vernacular languages and on the right-hand page, the picture itself. The visual unity of Amorum emblemata, derived mainly from the presence of the Cupid figure in all emblems but one, is recreated in Amoris divini emblemata through the ubiquitous presence of the figures of Amor Divinus (Divine love) and the soul. While there is some re-use of imagery from the earlier publication, the Amoris divini emblemata also contains many emblems which are not converted from Amorum emblemata.

Amoris divini emblemata was the starting point of a new tradition in religious emblem books and had an important influence on Herman Hugo's Pia desideria (1624).[20]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Belkin (1998): 26–28.

- ^ a b c d Otto van Veen at the Netherlands Institute for Art History

- ^ a b Van de Velde.

- ^ Otto van Veen on the site of Jean Moust gallery

- ^ a b c Octavio van Veen in Karel van Mander's Schilderboeck, 1604 (in Dutch)

- ^ Bertini (1998): 119.

- ^ Brinio op het schild geheven Painting by Otto van Veen

- ^ "Batavians defeating Roman at the Rijksmuseum". Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Olga Vassilieva-Codognet, Coining Neo-Stoic Hieroglyphs: from the Brussels Mint to Emblemata sive symbola, in: Otto Vaenius and his Emblem Books, ed. Simon McKeown (Glasgow Emblem Studies, 15), Glasgow 2012, pp. 211–248

- ^ Profile of Apollonia van Veen in the Dictionary of Pastellists Before 1800.

- ^ Gertruida van Veen (1602–1643) at the Netherlands Institute for Art History

- ^ (in Dutch) Octavio van Veen biography in De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen (1718) by Arnold Houbraken

- ^ a b c The Q. Horatii Flacci emblemata at the Emblem Project Utrecht

- ^ The Invention of the Emblem Book and the Transmission of Knowledge, ca. 1510–1610, Karl A.E. Enenkel, 2019 - Chapter 7 "The Transmission of Knowledge via Pictorial Figurations: Vaenius’ Emblemata Horatiana (1607) as a Manual of Ethics"

- ^ Enenkel, p 366

- ^ Otto Vaenius, Amorum Emblemata, 1608, Hieronymus Verdussen, Antwerp

- ^ Julie Coleman, Otto van Veen Amorum Emblemata, February 2001, Special Collections Department, Library, University of Glasgow, Hillhead Street, G12 8QE, Scotland, United Kingdom

- ^ Montone, p. 47.

- ^ Otto van Veen's Amorum Emblemata, 1608, Ghewensten Strijdt / Combat Heureux

- ^ The Amoris divini emblemata at the Emblem Project Utrecht

References

[edit]- Belkin, Kristin Lohse: Rubens. Phaidon Press, 1998. ISBN 0-7148-3412-2.

- Bertini, Giuseppe: "Otto van Veen, Cosimo Masi and the Art Market in Antwerp at the End of the Sixteenth Century." Burlington Magazine vol. 140, no. 1139. (Feb. 1998), pp. 119–120.

- Montone, Tina, "'Dolci ire, dolci sdegni, e dolci paci': The Role of the Italian Collaborator in the Making of Otto Vaenius's Amorum Emblemata," in Alison Adams and Marleen van der Weij, Emblems of the Low Countries: A Book Historical Perspective. Glasgow Emblem Studies, vol. 8. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2003. p. 47.

- Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Otto van Veen's Batavians defeating the Roman (sic)

- Van de Velde, Carl: "Veen [Vaenius; Venius], Otto van" Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press, [accessed 18 May 2007].

- Veen, Otto van. Amorum Emblemata... Emblemes of Love, with verses in Latin, English, and Italian. Antwerp: [Typis Henrici Swingenii] Venalia apud Auctorem, 1608.

External links

[edit] Media related to Otto van Veen at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Otto van Veen at Wikimedia Commons- Othonis Vaenii emblemata

- Emblem Project Utrecht – 3 editions of emblem books by Otto van Veen

- Amorum Emblemata 1608 on Internet Archive.

- Vita D. Thomae Aquinatis a manuscript by Otto van Veen (1610)