Sphenoid bone

| Sphenoid bone | |

|---|---|

Position of the sphenoid bone | |

Animation of the sphenoid bone | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os sphenoidale |

| MeSH | D013100 |

| TA98 | A02.1.05.001 |

| TA2 | 584 |

| FMA | 52736 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The sphenoid bone[note 1] is an unpaired bone of the neurocranium. It is situated in the middle of the skull towards the front, in front of the basilar part of the occipital bone. The sphenoid bone is one of the seven bones that articulate to form the orbit. Its shape somewhat resembles that of a butterfly, bat or wasp with its wings extended. The name presumably originates from this shape, since sphekodes (σφηκώδης) means wasp-like in ancient Greek.

Structure

[edit]

It is divided into the following parts:

- a median portion, known as the body of sphenoid bone, containing the sella turcica, which houses the pituitary gland as well as the paired paranasal sinuses, the sphenoidal sinuses[5]

- two greater wings on the lateral side of the body and two lesser wings from the anterior side.

- Pterygoid processes of the sphenoides, directed downwards from the junction of the body and the greater wings.[4]

Two sphenoidal conchae are situated at the anterior and inferior part of the body.

Intrinsic ligaments of the sphenoid

[edit]The more important of these are:

- the pterygospinous, which stretches between the spina angularis and the lateral pterygoid plate, superiorly attached to the root of the lateral pterygoid plate anteriorly;

- the interclinoid ligament, a band of dura mater that connects the anterior clinoid process and posterior clinoid process of the sphenoid bone;

- the caroticoclinoid, connecting the anterior to the middle clinoid process.

These ligaments occasionally ossify, though the incidence of ligamentous ossification (both partial and complete) varies according to the ligament type, with the interclinoid ligament being most commonly identified as having ossified and the pterygoalar ligament least commonly identified.[6]

Features

[edit]- pterygoid notch

- pterygoid fossa

- scaphoid fossa

- pterygoid hamulus

- pterygoid canal

- pterygospinous process

- sella turcica

Articulations

[edit]The sphenoid articulates with the frontal, parietal, ethmoid, temporal, zygomatic, palatine, vomer, and occipital bones and helps to connect the neurocranium to the facial skeleton.

Body of sphenoid

[edit]Superior or cerebral surface

[edit]Articulates with ethmoid bone anteriorly and basilar part of occipital bone posteriorly. It shows:

Inferior surface

[edit]- Rostrum of sphenoid

- Sphenoidal conchae

- Vaginal processes of medial pterygoid plate

Anterior surface

[edit]Sphenoidal crest articulates with the perpendicular plate of ethmoid leading to formation of a part of the septum of nose.

Posterior surface

[edit]Basilar part of occipital bone

Lateral surface

[edit]Carotid sulcus lodging cavernous sinus and internal carotid artery

Sphenoidal sinuses

[edit]Sphenoidal or sphenoid sinuses are asymmetrical air sinuses in the body of the sphenoid, closed by sphenoidal conchae.

Greater wings

[edit]Superior or cerebral surface

[edit]This forms the floor of the middle cranial fossa. It presents (starting from the front):

Lateral surface

[edit]This is divided into (by infratemporal crest):

- Upper or temporal surface

- Lower or infratemporal surface[4]

Foramen pierce it:

Orbital surface

[edit]This forms the posterior wall of the orbit [4]

Lesser wings

[edit]These are two triangular wings projecting laterally from anterosuperior part of the body. Each consists of:

- A base forming medial end of the wing.

- Tip forming the lateral end of the wing.

- Superior surface forming floor of anterior cranial fossa.

- Inferior surface forming upper boundary of superior orbital fissure.

- Posterior surface projects into the Sylvian point.

- Medially, terminates in the anterior clinoid process.[4]

Development

[edit]

Until the seventh or eighth month of fetal development, the body of the sphenoid consists of two parts: one in front of the tuberculum sellae, the presphenoid, with which the small wings are continuous; the other, consisting of the sella turcica and dorsum sellae, the postsphenoid, with which are associated the great wings, and pterygoid processes.

The greater part of the bone is ossified in cartilage. There are fourteen centers in all, six for the presphenoid and eight for the postsphenoid.

Presphenoid

[edit]By about the ninth week of fetal development an ossific center appears for each of the small wings (orbito-sphenoids) just lateral to the optic foramen; this is followed by the appearance of two nuclei in the presphenoid part of the body.

The sphenoidal conchae are each developed from a center that makes its appearance about the fifth month; at birth they consist of small triangular laminae, and it is not until the third year that they become hollowed out and coneshaped; about the fourth year they fuse with the labyrinths of the ethmoid bone, and between the ninth and twelfth years they unite with the sphenoid bone.

Postsphenoid

[edit]The first ossific nuclei are those for the great wings (alisphenoids). One makes its appearance in each wing between the foramen rotundum and foramen ovale about the eighth week. The orbital plate and that part of the sphenoid, which is found in the temporal fossa, as well as the lateral pterygoid plate, are ossified in membrane (Fawcett).

Soon after, the centers for the postsphenoid part of the body appear, one on either side of the sella turcica, and become blended together about the middle of fetal life.

Each medial pterygoid plate (except its hamulus) is ossified in membrane, and its center probably appears about the ninth or tenth week; the hamulus becomes chondrified during the third month, and almost at once ossifies (Fawcett).

The medial joins the lateral pterygoid plate about the sixth month.

About the fourth month, a center appears for each lingula and speedily joins the rest of the bone.

The presphenoid is united to the postsphenoid about the eighth month, and at birth the sphenoid is in three pieces [Fig. 4]: a central, consisting of the body and small wings, and two lateral, each comprising a great wing and pterygoid process.

In the first year after birth the great wings and body unite, and the small wings extend inward above the anterior part of the body, and, meeting with each other in the middle line, form an elevated smooth surface, termed the jugum sphenoidale.

By the twenty-fifth year the sphenoid and occipital are completely fused.

Between the pre- and postsphenoid there are occasionally seen the remains of a canal, the canalis cranio-pharyngeus, through which, in early fetal life, the hypophyseal diverticulum of the buccal ectoderm is transmitted.

The sphenoidal sinuses are present as minute cavities at the time of birth (Onodi), but do not attain their full size until after puberty.

Function

[edit]This bone assists with the formation of the base and the sides of the skull, and the floors and walls of the orbits. It is the site of attachment for most of the muscles of mastication. Many foramina and fissures are located in the sphenoid that carry nerves and blood vessels of the head and neck, such as the superior orbital fissure (with ophthalmic nerve), foramen rotundum (with maxillary nerve) and foramen ovale (with mandibular nerve).[7]

Other animals

[edit]The sphenoid bone of humans is homologous with a number of bones that are often separate in other animals, and have a somewhat complex arrangement.

In the early lobe-finned fishes and tetrapods, the pterygoid bones were flat, wing-like bones forming the major part of the roof of the mouth. Above the pterygoids were the epipterygoid bones, which formed part of a flexible joint between the braincase and the palatal region, as well as extending a vertical bar of bone towards the roof of the skull. Between the pterygoids lay an elongated, narrow parasphenoid bone, which also spread over some of the lower surface of the braincase, and connected, at its forward end, with a sphenethmoid bone helping to protect the olfactory nerves. Finally, the basisphenoid bone formed part of the floor of the braincase and lay immediately above the parasphenoid.[8]

Aside from the loss of the flexible joint at the rear of the palate, this primitive pattern is broadly retained in reptiles, albeit with some individual modifications. In birds, the epipterygoids are absent and the pterygoids considerably reduced. Living amphibians have a relatively simplified skull in this region; a broad parasphenoid forms the floor of the braincase, the pterygoids are relatively small, and all other related bones except the sphenethmoid are absent.[8]

In mammals, these various bones are often (though not always) fused into a single structure; the sphenoid. The basisphenoid forms the posterior part of the base, while the pterygoid processes represent the pterygoid bones. The epipterygoids have extended into the wall of the cranium; they are referred to as alisphenoids when separate in mammals, and form the greater wings of the sphenoid when fused into a larger structure. The sphenethmoid bone forms as three bones: the lesser wings and the anterior part of the base. These two parts of the sphenethmoid may be distinguished as orbitosphenoids and presphenoid, respectively, although there is often some degree of fusion. Only the parasphenoid appears to be entirely absent in mammals.[8]

In the dog the sphenoid is represented by 8 bones: basisphenoid, alisphenoids, presphenoid, orbitosphenoids, pterygoids. These bones remain separate and are the:

- 2 Alisphenoids: each greater wing

- 2 Orbitosphenoids: each lesser wing

- Basisphenoid: back part of body

- Presphenoid: front part of body

- 2 Pterygoids: medial pterygoid plate

Additional images

[edit]-

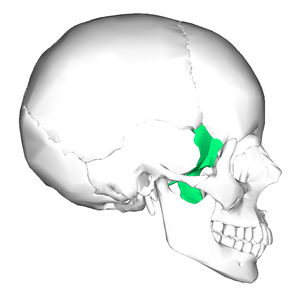

Position of sphenoid bone (shown in green). Animation.

-

Seen from below (mandible is removed)

-

Seen from above (parietal bones are removed)

-

Shape of sphenoid bone.

-

Facial bones.

-

Lateral wall of nasal cavity, showing ethmoid bone in position.

-

Base of skull. Inferior surface.

-

Lateral view of the skull.

-

Horizontal section of nasal and orbital cavities.

-

Floor of the skull.

-

Roof, floor, and lateral wall of left nasal cavity.

-

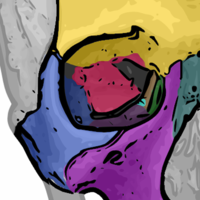

The skull from the front. The sphenoid is labeled with yellow to the left of the picture, both in the orbit and behind the zygomatic process

-

Sphenoid bone

-

Sphenoid bone superior view

-

Sphenoid bone and temporal bones

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ According to most dictionaries, the word sphenoid (/ˈsfiːnɔɪd/[1][2]) derives from Greek sphenoeides, "wedgelike". Thieme Atlas of Anatomy[3] disagrees and says that the sphenoid bone was originally called os sphecoidale, meaning "bone resembling a wasp", and that the word was later written 'sphenoidale' by a transcription error. An anterior view of the bone resembles more the body of a wasp or a bat[4] with wings than a wedge.

References

[edit]- ^ OED 2nd edition, 1989.

- ^ Entry "sphenoid" in Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary.

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy, Head and Neuroanatomy 2011

- ^ a b c d e f g h Chaurasia (31 January 2013). Human Anatomy Volume Three. CBS Publishers & Distributors. pp. 43–45. ISBN 978-81-239-2332-1.

- ^ Jacob (2008). Human Anatomy. Elsevier. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-443-10373-5.

- ^ Touska, P., Hasso, S., Oztek, A. et al. Skull base ligamentous mineralisation: evaluation using computed tomography and a review of the clinical relevance. Insights Imaging 10, 55 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-019-0740-8

- ^ Fehrenbach; Herring (2012). Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck. Elsevier. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4377-2419-6.

- ^ a b c Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 220–244. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 147 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 147 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

External links

[edit]- Anatomy figure: 22:01-06 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Lateral view of skull."