Orpheus in the Underworld

Orpheus in the Underworld[1] and Orpheus in Hell[2] are English names for Orphée aux enfers (French: [ɔʁfe oz‿ɑ̃fɛʁ]), a comic opera with music by Jacques Offenbach and words by Hector Crémieux and Ludovic Halévy. It was first performed as a two-act "opéra bouffon" at the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, Paris, on 21 October 1858, and was extensively revised and expanded in a four-act "opéra féerie" version, presented at the Théâtre de la Gaîté, Paris, on 7 February 1874.

The opera is a lampoon of the ancient legend of Orpheus and Eurydice. In this version Orpheus is not the son of Apollo but a rustic violin teacher. He is glad to be rid of his wife, Eurydice, when she is abducted by the god of the underworld, Pluto. Orpheus has to be bullied by Public Opinion into trying to rescue Eurydice. The reprehensible conduct of the gods of Olympus in the opera was widely seen as a veiled satire of the court and government of Napoleon III, Emperor of the French. Some critics expressed outrage at the librettists' disrespect for classic mythology and the composer's parody of Gluck's opera Orfeo ed Euridice; others praised the piece highly.

Orphée aux enfers was Offenbach's first full-length opera. The original 1858 production became a box-office success, and ran well into the following year, rescuing Offenbach and his Bouffes company from financial difficulty. The 1874 revival broke records at the Gaîté's box-office. The work was frequently staged in France and internationally during the composer's lifetime and throughout the 20th century. It is one of his most often performed operas, and continues to be revived in the 21st century.

In the last decade of the 19th century the Paris cabarets the Moulin Rouge and Folies Bergère adopted the music of the "Galop infernal" from the culminating scene of the opera to accompany the can-can, and ever since then the tune has been popularly associated with the dance.

Background and first productions

[edit]

Between 1855 and 1858 Offenbach presented more than two dozen one-act operettas, first at the Bouffes-Parisiens, Salle Lacaze, and then at the Bouffes-Parisiens, Salle Choiseul. The theatrical licensing laws then permitted him only four singers in any piece, and with such small casts, full-length works were out of the question.[3] In 1858 the licensing restrictions were relaxed, and Offenbach was free to go ahead with a two-act work that had been in his mind for some time. Two years earlier he had told his friend the writer Hector Crémieux that when he was musical director of the Comédie-Française in the early 1850s he swore revenge for the boredom he suffered from the posturings of mythical heroes and gods of Olympus in the plays presented there.[4] Cremieux and Ludovic Halévy sketched out a libretto for him lampooning such characters.[5][n 1] By 1858, when Offenbach was finally allowed a large enough cast to do the theme justice, Halévy was preoccupied with his work as a senior civil servant, and the final libretto was credited to Crémieux alone.[3][n 2] Most of the roles were written with popular members of the Bouffes company in mind, including Désiré, Léonce, Lise Tautin, and Henri Tayau as an Orphée who could actually play Orpheus's violin.[1][n 3]

The first performance took place at the Salle Choiseul on 21 October 1858. At first the piece did reasonably well at the box-office but was not the tremendous success Offenbach had hoped for. He insisted on lavish stagings for his operas: expenses were apt to outrun receipts, and he was in need of a substantial money-spinner.[8] Business received an inadvertent boost from the critic Jules Janin of the Journal des débats. He had praised earlier productions at the Bouffes-Parisiens but was roused to vehement indignation at what he maintained was a blasphemous, lascivious outrage – "a profanation of holy and glorious antiquity".[9] His attack, and the irreverent public ripostes by Crémieux and Offenbach, made headlines and provoked huge interest in the piece among the Parisian public, who flocked to see it.[9][n 4] In his 1980 study of Offenbach, Alexander Faris writes, "Orphée became not only a triumph, but a cult."[14][n 5] It ran for 228 performances, at a time when a run of 100 nights was considered a success.[16] Albert Lasalle, in his history of the Bouffes-Parisiens (1860), wrote that the piece closed in June 1859 – although it was still performing strongly at the box-office – "because the actors, who could not tire the public, were themselves exhausted".[17]

In 1874 Offenbach substantially expanded the piece, doubling the length of the score and turning the intimate opéra bouffon of 1858 into a four-act opéra féerie extravaganza, with substantial ballet sequences. This version opened at the Théâtre de la Gaîté on 7 February 1874, ran for 290 performances,[18] and broke box-office records for that theatre.[19][n 6] During the first run of the revised version Offenbach expanded it even further, adding ballets illustrating the kingdom of Neptune in Act 3[n 7] and bringing the total number of scenes in the four acts to twenty-two.[19][n 8]

Roles

[edit]| Role | Voice type[n 9] | Premiere cast (two-act version), 21 October 1858(Conductor: Jacques Offenbach)[25] | Premiere cast (four-act version), 7 February 1874(Conductor: Albert Vizentini)[17][26] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pluton (Pluto), god of the underworld, disguised as Aristée (Aristaeus), a shepherd | tenor | Léonce | Achille-Félix Montaubry |

| Jupiter, king of the gods | low tenor or high baritone | Désiré | Christian |

| Orphée (Orpheus), a musician | tenor | Henri Tayau | Meyronnet |

| John Styx, servant of Pluton, formerly king of Boeotia | tenor or baritone | Bache | Alexandre, fils |

| Mercure (Mercury), messenger of the gods | tenor | J. Paul | Pierre Grivot |

| Bacchus, god of wine | spoken | Antognini | Chevalier |

| Mars, god of war | bass | Floquet | Gravier |

| Eurydice, wife of Orphée | soprano | Lise Tautin | Marie Cico |

| Diane (Diana), goddess of chastity | soprano | Chabert | Berthe Perret |

| L'Opinion publique (Public Opinion) | mezzo-soprano | Marguerite Macé-Montrouge | Elvire Gilbert |

| Junon (Juno), wife of Jupiter | soprano or mezzo-soprano | Enjalbert | Pauline Lyon |

| Vénus (Venus), goddess of beauty | soprano | Marie Garnier | Angèle |

| Cupidon (Cupid), god of love | soprano (en travesti) | Coralie Geoffroy | Matz-Ferrare |

| Minerve (Minerva), goddess of wisdom | soprano | Marie Cico | Castello |

| Morphée (Morpheus), god of sleep | tenor | –[n 10] | Damourette |

| Cybèle (Cybele), goddess of nature | soprano | – | Maury |

| Pomone (Pomona), goddess of fruits | soprano | – | Durieu |

| Flore (Flora), goddess of flowers | soprano | – | B. Mery |

| Cérès (Ceres), goddess of agriculture | soprano | – | Iriart |

| Amour | mezzo-soprano | – | Matz-Ferrare |

| Cerbère (Cerberus), three-headed guardian of the underworld | barked | Tautin, snr.[n 11] | Monet |

| Minos | baritone/tenor | – | Scipion |

| Éaque (Aeacus) | tenor | – | Jean Paul |

| Rhadamante (Rhadamanthus) | bass | – | J. Vizentini |

| Gods, goddesses, muses, shepherds, shepherdesses, lictors and spirits in the underworld | |||

Synopsis

[edit]Original two-act version

[edit]Act 1, Scene 1: The countryside near Thebes, Ancient Greece

[edit]A spoken introduction with orchestral accompaniment (Introduction and Melodrame) opens the work. Public Opinion explains who she is – the guardian of morality ("Qui suis-je? du Théâtre Antique").[28] She says that unlike the chorus in Ancient Greek plays she does not merely comment on the action, but intervenes in it, to make sure the story maintains a high moral tone. Her efforts are hampered by the facts of the matter: Orphée is not the son of Apollo, as in classical myth, but a rustic teacher of music, whose dislike of his wife, Eurydice, is heartily reciprocated. She is in love with the shepherd, Aristée (Aristaeus), who lives next door ("La femme dont le coeur rêve"),[29] and Orphée is in love with Chloë, a shepherdess. When Orphée mistakes Eurydice for her, everything comes out, and Eurydice insists they abandon the marriage. Orphée, fearing Public Opinion's reaction, torments his wife into keeping the scandal quiet using violin music, which she hates ("Ah, c'est ainsi").[30]

Aristée enters. Though seemingly a shepherd he is in reality Pluton (Pluto), God of the Underworld. He keeps up his disguise by singing a pastoral song about sheep ("Moi, je suis Aristée").[31] Eurydice has discovered what she thinks is a plot by Orphée to kill Aristée – letting snakes loose in the fields – but is in fact a conspiracy between Orphée and Pluton to kill her, so that Pluton may have her and Orphée be rid of her. Pluton tricks her into walking into the trap by showing immunity to it, and she is bitten.[n 12] As she dies, Pluton transforms into his true form (Transformation Scene).[33] Eurydice finds that death is not so bad when the God of Death is in love with one ("La mort m'apparaît souriante").[34] They descend into the Underworld as soon as Eurydice has left a note telling her husband she has been unavoidably detained.[35]

All seems to be going well for Orphée until Public Opinion catches up with him, and threatens to ruin his violin teaching career unless he goes to rescue his wife. Orphée reluctantly agrees.[36]

Act 1, Scene 2: Olympus

[edit]The scene changes to Olympus, where the Gods are sleeping ("Dormons, dormons"). Cupidon and Vénus enter separately from amatory nocturnal escapades and join their sleeping colleagues,[n 13] but everyone is soon woken by the sound of the horn of Diane, supposedly chaste huntress and goddess.[38] She laments the sudden absence of Actaeon, her current love ("Quand Diane descend dans la plaine");[39] to her indignation, Jupiter tells her he has turned Actaeon into a stag to protect her reputation.[40] Mercury arrives and reports that he has visited the Underworld, to which Pluton has just returned with a beautiful woman.[41] Pluton enters, and is taken to task by Jupiter for his scandalous private life.[42] To Pluton's relief the other Gods choose this moment to revolt against Jupiter's reign, their boring diet of ambrosia and nectar, and the sheer tedium of Olympus ("Aux armes, dieux et demi-dieux!").[43] Jupiter's demands to know what is going on lead them to point out his hypocrisy in detail, poking fun at all his mythological affairs ("Pour séduire Alcmène la fière").[44]

Orphée's arrival, with Public Opinion at his side, has the gods on their best behaviour ("Il approche! Il s'avance").[45] Orphée obeys Public Opinion and pretends to be pining for Eurydice: he illustrates his supposed pain with a snatch of "Che farò senza Euridice" from Gluck's Orfeo.[46] Pluton is worried he will be forced to give Eurydice back; Jupiter announces that he is going to the Underworld to sort everything out. The other gods beg to come with him, he consents, and mass celebrations break out at this holiday ("Gloire! gloire à Jupiter... Partons, partons").[47]

Act 2, Scene 1: Pluton's boudoir in the Underworld

[edit]

Eurydice is being kept locked up by Pluton, and is finding life very tedious. Her gaoler is a dull-witted tippler by the name of John Styx. Before he died, he was King of Boeotia (a region of Greece that Aristophanes made synonymous with country bumpkins),[48] and he sings Eurydice a doleful lament for his lost kingship ("Quand j'étais roi de Béotie").[49]

Jupiter discovers where Pluton has hidden Eurydice, and slips through the keyhole by turning into a beautiful, golden fly. He meets Eurydice on the other side, and sings a love duet with her where his part consists entirely of buzzing ("Duo de la mouche").[50] Afterwards, he reveals himself to her, and promises to help her, largely because he wants her for himself. Pluton is left furiously berating John Styx.[51]

Act 2, Scene 2: The banks of the Styx

[edit]The scene shifts to a huge party the gods are having, where ambrosia, nectar, and propriety are nowhere to be seen ("Vive le vin! Vive Pluton!").[52] Eurydice is present, disguised as a bacchante ("J'ai vu le dieu Bacchus"),[53] but Jupiter's plan to sneak her out is interrupted by calls for a dance. Jupiter insists on a minuet, which everybody else finds boring ("La la la. Le menuet n'est vraiment si charmant"). Things liven up as the most famous number in the opera, the "Galop infernal", begins, and all present throw themselves into it with wild abandon ("Ce bal est original").[54]

Ominous violin music heralds the approach of Orphée (Entrance of Orphée and Public Opinion),[55] but Jupiter has a plan, and promises to keep Eurydice away from her husband. As with the standard myth, Orphée must not look back, or he will lose Eurydice forever ("Ne regarde pas en arrière!").[56] Public Opinion keeps a close eye on him, to keep him from cheating, but Jupiter throws a lightning bolt, making him jump and look back, and Eurydice vanishes.[57] Amid the ensuing turmoil, Jupiter proclaims that she will henceforth belong to the god Bacchus and become one of his priestesses. Public Opinion is not pleased, but Pluton has had enough of Eurydice, Orphée is free of her, and all ends happily.[58]

Revised 1874 version

[edit]The plot is essentially that of the 1858 version. Instead of two acts with two scenes apiece, the later version is in four acts, which follow the plot of the four scenes of the original. The revised version differs from the first in having several interpolated ballet sequences, and some extra characters and musical numbers. The additions do not affect the main narrative but add considerably to the length of the score.[n 14] In Act I there is an opening chorus for assembled shepherds and shepherdesses, and Orpheus has a group of youthful violin students, who bid him farewell at the end of the act. In Act 2 Mercure is given a solo entrance number ("Eh hop!"). In Act 3, Eurydice has a new solo, the "Couplets des regrets" ("Ah! quelle triste destinée!"), Cupidon has a new number, the "Couplets des baisers" ("Allons, mes fins limiers"), the three judges of Hades and a little band of policemen are added to the cast to be involved in Jupiter's search for the concealed Eurydice, and at the end of the act the furious Pluton is seized and carried off by a swarm of flies.[59][60]

Music

[edit]The score of the opera, which formed the pattern for the many full-length Offenbach operas that followed, is described by Faris as having an "abundance of couplets" (songs with repeated verses for one or more singers), "a variety of other solos and duets, several big choruses, and two extended finales". Offenbach wrote in a variety of styles – from Rococo pastoral vein, via pastiche of Italian opera, to the uproarious galop – displaying, in Faris's analysis, many of his personal hallmarks, such as melodies that "leap backwards and forwards in a remarkably acrobatic manner while still sounding not only smoothly lyrical, but spontaneous as well". In such up-tempo numbers as the "Galop infernal", Offenbach makes a virtue of simplicity, often keeping to the same key through most of the number, with largely unvarying instrumentation throughout.[61] Elsewhere in the score Offenbach gives the orchestra greater prominence. In the "duo de la mouche" Jupiter's part, consisting of buzzing like a fly, is accompanied by the first and second violins playing sul ponticello, to produce a similarly buzzing sound.[62] In Le Figaro, Gustave Lafargue remarked that Offenbach's use of a piccolo trill punctuated by a tap on a cymbal in the finale of the first scene was a modern recreation of an effect invented by Gluck in his score of Iphigénie en Aulide.[63] Wilfrid Mellers also remarks on Offenbach's use of the piccolo to enhance Eurydice's couplets with "girlish giggles" on the instrument.[64] Gervase Hughes comments on the elaborate scoring of the "ballet des mouches" [Act 3, 1874 version], and calls it "a tour de force" that could have inspired Tchaikovsky.[65]

Faris comments that in Orphée aux enfers Offenbach shows that he was a master of establishing mood by the use of rhythmic figures. Faris instances three numbers from the second act (1858 version), which all are in the key of A major and use identical notes in almost the same order, "but it would be hard to imagine a more extreme difference in feeling than that between the song of the King of the Boeotians and the Galop".[67] In a 2014 study Heather Hadlock comments that for the former, Offenbach composed "a languid yet restless melody" over a static musette-style drone-bass accompaniment of alternating dominant and tonic harmonies, simultaneously evoking and mocking nostalgia for a lost place and time and "creating a perpetually unresolved tension between pathos and irony".[68] Mellers finds that Styx's aria has "a pathos that touches the heart" – perhaps, he suggests, the only instance of true feeling in the opera.[69]

In 1999 Thomas Schipperges wrote in the International Journal of Musicology that many scholars hold that Offenbach's music defies all musicological methods. He did not agree, and analysed the "Galop infernal", finding it to be sophisticated in many details: "For all its straightforwardness, it reveals a calculated design. The overall 'economy' of the piece serves a deliberate musical dramaturgy."[70] Hadlock observes that although the best-known music in the opera is "driven by the propulsive energies of Rossinian comedy" and the up-tempo galop, such lively numbers go side by side with statelier music in an 18th-century vein: "The score's sophistication results from Offenbach's intertwining of contemporary urban musical language with a restrained and wistful tone that is undermined and ironized without ever being entirely undone".[71]

Orphée aux enfers was the first of Offenbach's major works to have a chorus.[n 15] In a 2017 study Melissa Cummins comments that although the composer used the chorus extensively as Pluton's minions, bored residents of Olympus, and bacchantes in Hades, they are merely there to fill out the vocal parts in the large ensemble numbers, and "are treated as a nameless, faceless crowd who just happen to be around."[73] In the Olympus scene the chorus has an unusual bocca chiusa section, marked "Bouche fermée", an effect later used by Bizet in Djamileh and Puccini in the "Humming Chorus" in Madama Butterfly.[74][75]

Editions

[edit]The orchestra at the Bouffes-Parisiens was small – probably about thirty players.[59] The 1858 version of Orphée aux enfers is scored for two flutes (the second doubling piccolo), one oboe, two clarinets, one bassoon, two horns, two cornets,[n 16] one trombone, timpani, percussion (bass drum/cymbals, triangle), and strings.[78] The Offenbach scholar Jean-Christophe Keck speculates that the string sections consisted of at most six first violins, four second violins, three violas, four cellos, and one double bass.[78] The 1874 score calls for considerably greater orchestral forces: Offenbach added additional parts for woodwind, brass and percussion sections. For the premiere of the revised version he engaged an orchestra of sixty players, as well as a military band of a further forty players for the procession of the gods from Olympus at the end of the second act.[79]

The music of the 1874 revision was well received by contemporary reviewers,[63][80] but some later critics have felt the longer score, with its extended ballet sections, has occasional dull patches.[23][81][82][n 14] Nonetheless, some of the added numbers, particularly Cupidon's "Couplets des baisers", Mercure's rondo "Eh hop", and the "Policeman's Chorus" have gained favour, and some or all are often added to performances otherwise using the 1858 text.[1][82][83]

For more than a century after the composer's death one cause of critical reservations about this and his other works was the persistence of what the musicologist Nigel Simeone has called "botched, butchered and bowdlerised" versions.[59] Since the beginning of the 21st century a project has been under way to release scholarly and reliable scores of Offenbach's operas, under the editorship of Keck. The first to be published, in 2002, was the 1858 version of Orphée aux enfers.[59] The Offenbach Edition Keck has subsequently published the 1874 score, and another drawing on both the 1858 and 1874 versions.[83]

Overture and galop

[edit]The best-known and much-recorded Orphée aux enfers overture[84] is not by Offenbach, and is not part of either the 1858 or the 1874 scores. It was arranged by the Austrian musician Carl Binder (1816–1860) for the first production of the opera in Vienna, in 1860.[84] Offenbach's 1858 score has a short orchestral introduction of 104 bars; it begins with a quiet melody for woodwind, followed by the theme of Jupiter's Act 2 minuet, in A♭ major and segues via a mock-pompous fugue in F major into Public Opinion's opening monologue.[85] The overture to the 1874 revision is a 393-bar piece, in which Jupiter's minuet and John Styx's song recur, interspersed with many themes from the score including "J'ai vu le Dieu Bacchus", the couplets "Je suis Vénus", the Rondeau des métamorphoses, the "Partons, partons" section of the Act 2 finale, and the Act 4 galop.[86][n 17]

Fifteen years or so after Offenbach's death the galop from Act 2 (or Act 4 in the 1874 version) became one of the world's most famous pieces of music,[59] when the Moulin Rouge and the Folies Bergère adopted it as the regular music for their can-can. Keck has commented that the original "infernal galop" was a considerably more spontaneous and riotous affair than the fin de siècle can-can (Keck likens the original to a modern rave) but the tune is now inseparable in the public mind from high-kicking female can-can dancers.[59]

Numbers

[edit]| 1858 version | 1874 version |

|---|---|

| Act 1: Scene 1 | Act 1 |

| Ouverture | Ouverture |

| "Qui je suis?" (Who am I?) – L'Opinion publique | Choeur des bergers: "Voici la douzième heure" (Shepherds' chorus: This is the twelfth hour) – Chorus, Le Licteur, L'Opinion publique |

| "Conseil municipal de la ville de Thèbes" (The Thebes Town Council) – Chorus | |

| "La femme dont le coeur rêve" | "La femme dont le cœur rêve" (The woman whose heart is dreaming) – Eurydice |

| Duo du concerto | Duo du concerto "Ah! C'est ainsi!" (Concerto duet: Ah, that's it!) – Orphée, Eurydice |

| Ballet pastoral | |

| "Moi, je suis Aristée" | "Moi, je suis Aristée" (I am Aristée) – Aristée |

| "La mort m'apparaît souriante" | "La mort m'apparaît souriante" (Death appears to me smiling) – Eurydice |

| "Libre! O bonheur!" (Free! Oh, joy!) – Orphée, Chorus | |

| "C'est l'Opinion publique" | "C'est l'Opinion publique" (It is Public Opinion) – L'Opinion publique, Orphée, Chorus |

| Valse des petits violonistes: "Adieu maestro" (Waltz of the little violinists) – Chorus, Orphée | |

| "Viens! C'est l'honneur qui t'appelle!" | "Viens! C'est l'honneur qui t'appelle!" (Come, it's honour that calls you) – L'Opinion publique, Orphée, Chorus |

| Act 1: Scene 2 | Act 2 |

| Entr'acte | Entr'acte |

| Choeur du sommeil | Choeur du sommeil – "Dormons, dormons" (Let's sleep) – Chorus |

| "Je suis Cupidon" – Cupidon, Vénus | "Je suis Vénus" – Vénus, Cupidon, Mars |

| Divertissement des songes et des heures (Divertissement of dreams and hours) "Tzing, tzing tzing" – Morphée | |

| "Par Saturne, quel est ce bruit" | "Par Saturne, quel est ce bruit" (By Saturn! What's that noise?) – Jupiter, Chorus |

| "Quand Diane descend dans la plaine" | "Quand Diane descend dans la plaine" (When Diana goes down to the plain) – Diane, Chorus |

| "Eh hop! eh hop! place à Mercure" (Hey presto! Make way for Mercury!) – Mercure, Junon, Jupiter | |

| Air en prose de Pluton: "Comme il me regarde!" (Pluton's prose aria: How he stares at me!) | |

| "Aux armes, dieux et demi-dieux!" | "Aux armes, dieux et demi-dieux!" (To arms, gods and demigods!) – Diane, Vénus, Cupidon, Chorus, Jupiter, Pluton |

| Rondeau des métamorphoses | Rondeau des métamorphoses: "Pour séduire Alcmène la fière" (To seduce the proud Alcmene) – Minerve, Diane, Cupidon, Vénus and Chorus (1858 version); Diane, Minerve, Cybèle, Pomone, Vénus, Flore, Cérès and Chorus (1874) |

| "Il approche! Il s'avance!" | "Il approche! Il s'avance" (He is close! Here he comes!) – Pluton, Les dieux, L'Opinion publique, Jupiter, Orphée, Mercure, Cupidon, Diane, Vénus |

| "Gloire! gloire à Jupiter... Partons, partons" | "Gloire! gloire à Jupiter... Partons, partons" (Glory to Jupiter! Let's go!) – Pluton, Les dieux, L'Opinion publique, Jupiter, Orphée, Mercure, Cupidon, Diane, Vénus |

| Act 2: Scene 1 | Act 3 |

| Entr'acte | Entr'acte |

| "Ah! quelle triste destinée!" (Ah! what a sad destiny) – Eurydice | |

| "Quand j'étais roi de Béotie" | "Quand j'étais roi de Béotie" (When I was king of Boeotia) – John Styx |

| "Minos, Eaque et Rhadamante" – Minos, Eaque, Rhadamante, Bailiff | |

| "Nez au vent, oeil au guet" (With nose in the air and watchful eye) – Policemen | |

| "Allons, mes fins limiers" (Onwards, my fine bloodhounds) – Cupidon and Policemen | |

| "Le beau bourdon que voilà" (What a handsome little bluebottle) – Policemen | |

| Duo de la mouche | Duo de la mouche "Il m'a semblé sur mon épaule" (Duet of the fly: It seemed to me on my shoulder) – Eurydice, Jupiter |

| Finale: "Bel insecte à l'aile dorée" | Finale: "Bel insecte à l'aile dorée" – (Beautiful insect with golden wing), Scène et ballet des mouches: Introduction, andante, valse, galop – Eurydice, Pluton, John Styx |

| Act 2: Scene 2 | Act 4 |

| Entr'acte | Entr'acte |

| "Vive le vin! Vive Pluton!" | "Vive le vin! Vive Pluton!"– Chorus |

| "Allons! ma belle bacchante" | "Allons! ma belle bacchante" (Go on, my beautiful bacchante) – Cupidon |

| "J'ai vu le Dieu Bacchus" | "J'ai vu le Dieu Bacchus" (I saw the God Bacchus) – Eurydice, Diane, Vénus, Cupidon, chorus |

| Menuet et Galop | Menuet et Galop "Maintenant, je veux, moi qui suis mince et fluet... Ce bal est original, d'un galop infernal" (Now, being slim and lithe I want... This ball is out of the ordinary: an infernal gallop) – All |

| Finale: "Ne regarde pas en arrière!" | Finale: "Ne regarde pas en arrière!" (Don't look back) – L'Opinion publique, Jupiter, Les dieux, Orphée, Eurydice |

Reception

[edit]19th century

[edit]

From the outset Orphée aux enfers divided critical opinion. Janin's furious condemnation did the work much more good than harm,[9] and was in contrast with the laudatory review of the premiere by Jules Noriac in the Figaro-Programme, which called the work, "unprecedented, splendid, outrageous, gracious, delightful, witty, amusing, successful, perfect, tuneful".[91][n 18] Bertrand Jouvin, in Le Figaro, criticised some of the cast but praised the staging – "a fantasy show, which has all the variety, all the surprises of fairy-opera".[93] The Revue et gazette musicale de Paris thought that though it would be wrong to expect too much in a piece of this genre, Orphée aux enfers was one of Offenbach's most outstanding works, with charming couplets for Eurydice, Aristée-Pluton and the King of Boeotia.[94] Le Ménestrel called the cast "thoroughbreds" who did full justice to "all the charming jokes, all the delicious originalities, all the farcical oddities thrown in profusion into Offenbach's music".[95]

Writing of the 1874 revised version, the authors of Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique said, "Orphée aux enfers is above all a good show. The music of Offenbach has retained its youth and spirit. The amusing operetta of yore has become a splendid extravaganza",[81] against which Félix Clément and Pierre Larousse wrote in their Dictionnaire des Opéras (1881) that the piece is "a coarse and grotesque parody" full of "vulgar and indecent scenes" that "give off an unhealthy smell".[96]

The opera was widely seen as containing thinly disguised satire of the régime of Napoleon III,[9][97] but the early press criticisms of the work focused on its mockery of revered classical authors such as Ovid[n 19] and the equally sacrosanct music of Gluck's Orfeo.[99][n 20] Faris comments that the satire perpetrated by Offenbach and his librettists was cheeky rather than hard-hitting,[101] and Richard Taruskin in his study of 19th-century music observes, "The calculated licentiousness and feigned sacrilege, which successfully baited the stuffier critics, were recognized by all for what they were – a social palliative, the very opposite of social criticism [...] The spectacle of the Olympian gods doing the cancan threatened nobody's dignity."[102] The Emperor greatly enjoyed Orphée aux enfers when he saw it at a command performance in 1860; he told Offenbach he would "never forget that dazzling evening".[103]

20th and 21st centuries

[edit]After Offenbach's death his reputation in France suffered a temporary eclipse. In Faris's words, his comic operas were "dismissed as irrelevant and meretricious souvenirs of a discredited Empire".[104] Obituarists in other countries similarly took it for granted that the comic operas, including Orphée, were ephemeral and would be forgotten.[105][106] By the time of the composer's centenary, in 1919, it had been clear for some years that such predictions had been wrong.[107] Orphée was frequently revived,[108] as were several more of his operas,[109] and criticisms on moral or musical grounds had largely ceased. Gabriel Groviez wrote in The Musical Quarterly:

The libretto of Orphée overflows with spirit and humour and the score is full of sparkling wit and melodious charm. It is impossible to analyse adequately a piece wherein the sublimest idiocy and the most astonishing fancy clash at every turn. [...] Offenbach never produced a more complete work.[110]

Among modern critics, Traubner describes Orphée as "the first great full-length classical French operetta [...] classical (in both senses of the term)", although he regards the 1874 revision as "overblown".[23] Peter Gammond writes that the public appreciated the frivolity of the work while recognising that it is rooted in the best traditions of opéra comique.[111] Among 21st-century writers Bernard Holland has commented that the music is "beautifully made, relentlessly cheerful, reluctantly serious", but does not show as the later Tales of Hoffmann does "what a profoundly gifted composer Offenbach really was";[112] Andrew Lamb has commented that although Orphée aux enfers has remained Offenbach's best-known work, "a consensus as to the best of his operettas would probably prefer La vie parisienne for its sparkle, La Périchole for its charm and La belle Hélène for its all-round brilliance".[113] Kurt Gänzl writes in The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre that compared with earlier efforts, Orphée aux enfers was "something on a different scale [...] a gloriously imaginative parody of classic mythology and of modern events decorated with Offenbach's most laughing bouffe music."[114] In a 2014 study of parody and burlesque in Orphée aux enfers, Hadlock writes:

With Orphée aux enfers, the genre we now know as operetta gathered its forces and leapt forward, while still retaining the quick, concise style of its one-act predecessors, their absurdist and risqué sensibility, and their economy in creating maximum comic impact with limited resources. At the same time, it reflects Offenbach's desire to establish himself and his company as legitimate heirs of the eighteenth-century French comic tradition of Philidor and Grétry.[115]

Revivals

[edit]France

[edit]

Between the first run and the first Paris revival, in 1860, the Bouffes-Parisiens company toured the French provinces, where Orphée aux enfers was reported as meeting with "immense" and "incredible" success".[116] Tautin was succeeded as Eurydice by Delphine Ugalde when the production was revived at the Bouffes-Parisiens in 1862 and again in 1867.[2]

The first revival of the 1874 version was at the Théâtre de la Gaîté in 1875 with Marie Blanche Peschard as Eurydice.[2] It was revived again there in January 1878 with Meyronnet (Orphée), Peschard (Eurydice), Christian (Jupiter), Habay (Pluton) and Pierre Grivot as both Mercure and John Styx,[117] For the Exposition Universelle season later that year Offenbach revived the piece again,[118] with Grivot as Orphée, Peschard as Eurydice,[119] the composer's old friend and rival Hervé as Jupiter[120] and Léonce as Pluton.[119] The opera was seen again at the Gaîté in 1887 with Taufenberger (Orphée), Jeanne Granier (Eurydice), Eugène Vauthier (Jupiter) and Alexandre (Pluton).[121] There was a revival at the Éden-Théâtre (1889) with Minart, Granier, Christian and Alexandre.[122]

20th-century revivals in Paris included productions at the Théâtre des Variétés (1902) with Charles Prince (Orphée), Juliette Méaly (Eurydice), Guy (Jupiter) and Albert Brasseur (Pluton),[123] and in 1912 with Paul Bourillon, Méaly, Guy and Prince;[124] the Théâtre Mogador (1931) with Adrien Lamy, Manse Beaujon, Max Dearly and Lucien Muratore;[125] the Opéra-Comique (1970) with Rémy Corazza, Anne-Marie Sanial, Michel Roux and Robert Andreozzi;[126] the Théâtre de la Gaïté-Lyrique (1972) with Jean Giraudeau, Jean Brun, Albert Voli and Sanial; and by the Théâtre français de l'Opérette at the Espace Cardin (1984) with multiple casts including (in alphabetical order) André Dran, Maarten Koningsberger, Martine March, Martine Masquelin, Marcel Quillevere, Ghyslaine Raphanel, Bernard Sinclair and Michel Trempont.[2] In January 1988 the work received its first performances at the Paris Opéra, with Michel Sénéchal (Orphée), Danielle Borst (Eurydice), François Le Roux (Jupiter), and Laurence Dale (Pluton).[127]

In December 1997 a production by Laurent Pelly was seen at the Opéra National de Lyon, where it was filmed for DVD, with Yann Beuron (Orphée), Natalie Dessay (Eurydice), Laurent Naouri (Jupiter) and Jean-Paul Fouchécourt (Pluton) with Marc Minkowski conducting.[128] The production originated in Geneva, where it had been given in September – in a former hydroelectric plant used while the stage area of the Grand Théâtre was being renovated – by a cast headed by Beuron, Annick Massis, Naouri, and Éric Huchet.[129]

Continental Europe

[edit]The first production outside France is believed to have been at Breslau in October 1859.[130] In December of the same year the opera opened in Prague. The work was given in German at the Carltheater, Vienna, in March 1860 in a version by Ludwig Kalisch, revised and embellished by Johann Nestroy, who played Jupiter. Making fun of Graeco-Roman mythology had a long tradition in the popular theatre of Vienna, and audiences had no difficulty with the disrespect that had outraged Jules Janin and others in Paris.[131] It was for this production that Carl Binder put together the version of the overture that is now the best known.[59] There were revivals at the same theatre in February and June 1861 (both given in French) and at the Theater an der Wien in January 1867. 1860 saw the work's local premieres in Brussels, Stockholm, Copenhagen and Berlin.[2] Productions followed in Warsaw, St Petersburg, and Budapest, and then Zurich, Madrid, Amsterdam, Milan and Naples.[130]

Gänzl mentions among "countless other productions [...] a large and glitzy German revival under Max Reinhardt" at the Großes Schauspielhaus, Berlin in 1922.[22][n 21] A more recent Berlin production was directed by Götz Friedrich in 1983;[132] a video of the production was released.[133] 2019 productions include those directed by Helmut Baumann at the Vienna Volksoper,[134] and by Barrie Kosky at the Haus für Mozart, Salzburg, with a cast headed by Anne Sophie von Otter as L'Opinion publique, a co-production between the Salzburg Festival, Komische Oper Berlin and Deutsche Oper am Rhein.[135]

Britain

[edit]

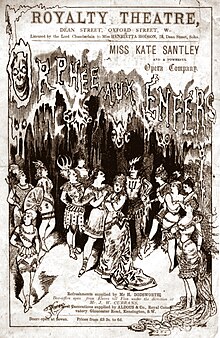

The first London production of the work was at Her Majesty's Theatre in December 1865, in an English version by J. R. Planché titled Orpheus in the Haymarket.[136][n 22] There were West End productions in the original French in 1869 and 1870 by companies headed by Hortense Schneider.[137][138][n 23] English versions followed by Alfred Thompson (1876) and Henry S. Leigh (1877).[139][140][n 24] An adaptation by Herbert Beerbohm Tree and Alfred Noyes opened at His Majesty's in 1911.[141][n 25] The opera was not seen again in London until 1960, when a new adaptation by Geoffrey Dunn opened at Sadler's Wells Theatre;[142][n 26] this production by Wendy Toye was frequently revived between 1960 and 1974.[143] An English version by Snoo Wilson for English National Opera (ENO), mounted at the London Coliseum in 1985,[144] was revived there in 1987.[145] A co-production by Opera North and the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company in a version by Jeremy Sams opened in 1992 and was revived several times.[146] In 2019 ENO presented a new production directed by Emma Rice, which opened to unfavourable reviews.[147]

Outside Europe

[edit]The first New York production was at the Stadt Theater, in German, in March 1861; the production ran until February 1862. Two more productions were sung in German: December 1863 with Fritze, Knorr, Klein and Frin von Hedemann and December 1866 with Brügmann, Knorr, Klein and Frin Steglich-Fuchs.[2] The opera was produced at the Theatre Français in January 1867 with Elvira Naddie, and at the Fifth Avenue Theatre in April 1868 with Lucille Tostée. In December 1883 it was produced at the Bijou Theatre with Max Freeman, Marie Vanoni, Digby Bell and Harry Pepper.[2] There were productions in Rio de Janeiro in 1865, Buenos Aires in 1866, Mexico City in 1867 and Valparaiso in 1868.[130] The opera was first staged in Australia at the Princess Theatre, Melbourne in March 1872, in Planché's London text, with Alice May as Eurydice.[148]

A spectacular production by Reinhardt was presented in New York in 1926.[149] The New York City Opera staged the work, conducted by Erich Leinsdorf, in 1956, with Sylvia Stahlman as Eurydice and Norman Kelley as Pluto.[150] More recent US productions have included a 1985 version by Santa Fe Opera,[151] and the 1985 ENO version, which was staged in the US by the Houston Grand Opera (co-producers) in 1986, and Los Angeles Opera in 1989.[152]

21st century worldwide

[edit]In April 2019 the Operabase website recorded 25 past or scheduled productions of the opera from 2016 onwards, in French or in translation: nine in Germany, four in France, two in Britain, two in Switzerland, two in the US, and productions in Gdańsk, Liège, Ljubljana, Malmö, Prague and Tokyo.[153]

Recordings

[edit]

Audio

[edit]In French

[edit]There are three full-length recordings. The first, from 1951 features the Paris Philharmonic Chorus and Orchestra, conducted by René Leibowitz, with Jean Mollien (Orphée), Claudine Collart (Eurydice), Bernard Demigny (Jupiter) and André Dran (Pluton); it uses the 1858 version.[154] A 1978 issue from EMI employs the expanded 1874 version; it features the Chorus and Orchestra of the Toulouse Capitol conducted by Michel Plasson, with Michel Sénéchal (Orphée), Mady Mesplé (Eurydice), Michel Trempont (Jupiter) and Charles Burles (Pluton).[155] A 1997 recording of the 1858 score with some additions from the 1874 revision features the Chorus and Orchestra of the Opéra National de Lyon, conducted by Marc Minkowski, with Yann Beuron (Orphée), Natalie Dessay (Eurydice), Laurent Naouri (Jupiter) and Jean-Paul Fouchécourt (Pluton).[156]

In English

[edit]As at 2022[update] the only recording of the full work made in English is the 1995 D'Oyly Carte production, conducted by John Owen Edwards with David Fieldsend (Orpheus), Mary Hegarty (Eurydice), Richard Suart (Jupiter), and Barry Patterson (Pluto). It uses the 1858 score with some additions from the 1874 revision. The English text is by Jeremy Sams.[157] Extended excerpts were recorded of two earlier productions: Sadler's Wells (1960), conducted by Alexander Faris, with June Bronhill as Eurydice and Eric Shilling as Jupiter;[158] and English National Opera (1985), conducted by Mark Elder, with Stuart Kale (Orpheus), Lillian Watson (Eurydice), Richard Angas (Jupiter) and Émile Belcourt (Pluto).[159]

In German

[edit]There have been three full-length recordings in German. The first, recorded in 1958, features the North German Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus conducted by Paul Burkhard, with Heinz Hoppe (Orpheus), Anneliese Rothenberger as Eurydice (Eurydike), Max Hansen as Jupiter and Ferry Gruber as Pluto.[160] Rothenberger repeated her role in a 1978 EMI set, with the Philharmonia Hungarica and Cologne Opera Chorus conducted by Willy Mattes, with Adolf Dellapozza (Orpheus), Benno Kusche (Jupiter) and Gruber (Pluto).[161] A recording based on the 1983 Berlin production by Götz Friedrich features the Orchestra and Chorus of Deutsche Oper Berlin, conducted by Jesús López Cobos, with Donald Grobe (Orpheus), Julia Migenes (Eurydike), Hans Beirer (Jupiter) and George Shirley (Pluto).[162]

Video

[edit]Recordings have been released on DVD based on Herbert Wernicke's 1997 production at the Théâtre de la Monnaie, Brussels, with Alexandru Badea (Orpheus), Elizabeth Vidal (Eurydice), Dale Duesing (Jupiter) and Reinaldo Macias (Pluton),[163] and Laurent Pelly's production from the same year, with Natalie Dessay (Eurydice), Yann Beuron (Orphée), Laurent Naouri (Jupiter) and Jean-Paul Fouchécourt (Pluton).[128] A version in English made for the BBC in 1983 has been issued on DVD. It is conducted by Faris and features Alexander Oliver (Orpheus), Lillian Watson (Eurydice), Denis Quilley (Jupiter) and Émile Belcourt (Pluto).[164] The Berlin production by Friedrich was filmed in 1984 and has been released as a DVD;[133] a DVD of the Salzburg Festival production directed by Kosky was published in 2019.[165]

Notes, references and sources

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The original sketch contained only four characters, Jupiter, Pluton, Eurydice and Proserpine.[5]

- ^ Halévy, mindful of his reputation as a senior government official, contributed anonymously though extensively to the final version of the text. Offenbach and Crémieux dedicated the work to him.[6]

- ^ Ovid's and Gluck's Orpheus, the son of Apollo, plays the lyre; Crémieux makes him a rustic violin teacher.[7]

- ^ Janin's article was published on 6 December 1858;[10][11][12] Crémieux's riposte was published in Le Figaro on 12 December 1858.[11] Alexander Faris and Richard Traubner incorrectly date the events to the following February.[13]

- ^ Peter Gammond (1980) adds that the public kept sneaking into the theatre, hoping not to be seen by anyone they knew.[15]

- ^ The production took 1,784,683 francs at the box office,[20] roughly equivalent in 2015 terms to €7,234,820.[21]

- ^ This interlude consisted of ten tableaux, including "Toads and Chinese fish", "Prawns and shrimps", "March of the Tritons", "Sea-horses' polka", "Pas de trois for seaweed", and "Pas de quatre for flowers and flying fish".[22]

- ^ According to The Penguin Opera Guide the running time of the 1858 version is 1 hour 45 minutes, and that of the 1874 revision 2 hours 45 minutes.[23]

- ^ The characters' tessiture are as indicated in the 2002 edition of the orchestral score; Offenbach, writing with particular performers in mind, seldom stipulated a vocal range in his manuscripts.[24]

- ^ The role of Morphée appears in the earliest version of Oprhée aux enfers, but Offenbach cut it before the first performance. There were two other roles, Hébé and Cybèle, that the composer cut.[24]

- ^ The role and player are not listed in Crémieux's published libretto or the 1859 vocal score. Faris mentions a scene cut in February 1859 during the first run.[14] In his review in Le Ménestrel of the October 1858 premiere Alexis Dureau included in his plot summary a scene in which Jupiter gets Cerberus and Charon drunk so that he can smuggle Eurydice out of the Underworld.[7] This scene is not in the printed libretto.[27]

- ^ In their plot summary in Gänzl's Book of Musical Theatre, Kurt Gänzl and Andrew Lamb write "she gets an asp in the ankle".[32]

- ^ In the 1874 revision a third verse is added for Mars, also returning from a night on the tiles.[37]

- ^ a b The 1858 version of the vocal score runs to 147 pages; the 1874 vocal score issued by the same firm is 301 pages long.[59]

- ^ There were choruses in his earlier one-act pieces Ba-ta-clan (1855) and Mesdames de la Halle (1858).[72]

- ^ Offenbach specified cornets in this score; in other operas, such as La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein he wrote for trumpets.[76] In modern theatre orchestras cornet parts are often played on trumpets.[77]

- ^ Both of Offenbach's overtures are shorter than Binder's, the 1858 introduction particularly so: it plays for 3 minutes 6 seconds in the EMI recording conducted by Marc Minkowski.[87] The 1874 overture, reconstructed by Keck, plays for 8 minutes 47 seconds in a recording by Les Musiciens du Louvre conducted by Minkowski.[88] In recordings of Binder's arrangement conducted by René Leibowitz, Ernest Ansermet, Neville Marriner and Herbert von Karajan the playing time is between 9 and 10 minutes.[89]

- ^ "Inouï, Splendide, Ébouriffant, Gracieux, Charmant, Spirituel, Amusant, Réussi, Parfait, Mélodieux." Noriac printed each word on a new line for emphasis.[92]

- ^ One of Offenbach's biographers, Siegfried Kracauer, suggests that critics like Janin shied away from confronting the political satire, preferring to accuse Offenbach of disrespect of the classics.[98]

- ^ Gluck was not the only composer whom Offenbach parodied in Orphée aux enfers: Auber's venerated opera La muette de Portici is also quoted in the scene where the gods rebel against Jupiter,[100] as is La Marseillaise – a risky venture on the composer's part as the song was banned under the Second Empire as a "chant séditieux".[70]

- ^ Gänzl notes that initially other Offenbach operas were more popular in other countries – La belle Hélène in Austria and Hungary, Geneviève de Brabant in Britain and La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein in the US – Orphée was always the favourite in Germany.[22]

- ^ This production featured David Fisher (Orpheus), Louise Keeley (Eurydice), William Farren (Jupiter) and (Thomas?) Bartleman (Pluto).[136]

- ^ In the 1869 cast at the St James's Theatre, Schneider appeared with M. Beance (Orphée), L. Desmonts (Jupiter) and José Dupuis (Pluton);[137] in 1870, at the Princess's Theatre, she appeared with Henri Tayau (Orphée), M. Desmonts (Jupiter) and M. Carrier (Pluton).[138]

- ^ These productions were at Royalty Theatre and the Alhambra Theatre, and featured, respectively, Walter Fisher (Orpheus), Kate Santley (Eurydice), J. D. Stoyle (Jupiter) and Henry Hallam (Pluto),[139] and M. Loredan (Orpheus), Kate Munroe (Eurydice), Harry Paulton (Jupiter) and W. H. Woodfield (Pluto).[140]

- ^ The 1911 production had additional music by Frederic Norton, and featured Courtice Pounds (Orpheus), Eleanor Perry (Eurydice), Frank Stanmore (Jupiter) and Lionel Mackinder (Pluto).[141]

- ^ The 1960 production featured Kevin Miller (Orpheus), June Bronhill (Eurydice), Eric Shilling (Jupiter) and Jon Weaving (Pluto).[142]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Lamb, Andrew. "Orphée aux enfers", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2002. Retrieved 27 April 2019 (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e f g Gänzl and Lamb, p. 276

- ^ a b Gammond, p. 49

- ^ Teneo, Martial. "Jacques Offenbach: His Centenary" Archived 15 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Musical Quarterly, January 1920, pp. 98–117

- ^ a b Luez, p. 106

- ^ Kracauer, p. 173; and Faris, pp. 62–63

- ^ a b Dureau, Alexis. "Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens", Le Ménestrel, 24 October 1859, p. 3 (in French)

- ^ Gammond, p. 49; and Yon, p. 213

- ^ a b c d Gammond, p. 54

- ^ "Feuilleton du Journal des débats", Journal des débats politiques et littéraires, 6 December 1858, p. 1 (in French)

- ^ a b "Correspondance", Le Figaro, 12 December 1858, p. 5 (in French)

- ^ Hadlock, p. 177; and Yon, pp. 211–212

- ^ Faris, p. 71; and Traubner (2003), p. 32

- ^ a b Faris, p. 71

- ^ Gammond, p. 53

- ^ "Edmond Audran" Archived 30 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Opérette – Théâtre Musical, Académie Nationale de l'Opérette (in French). Retrieved 16 April 2019

- ^ a b "Orphée aux enfers" Archived 2 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopédie de l'art lyrique français, Association l'art lyrique français (in French). Retrieved 26 April 2019

- ^ "Le succès au théâtre", Le Figaro, 23 August 1891, p. 2

- ^ a b "Orphée aux enfers" Archived 21 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Opérette – Théâtre Musical, Académie Nationale de l'Opérette (in French). Retrieved 21 April 2019

- ^ "The Drama in Paris", The Era, 29 August 1891, p. 9

- ^ "Historical currency converter" Archived 15 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Historicalstatistics.org. Retrieved 21 April 2019

- ^ a b c Gänzl, p. 1552

- ^ a b c Traubner (1997), pp. 267–268

- ^ a b Offenbach-Keck, p. 6

- ^ Offenbach (1859), unnumbered introductory page; and Crémieux, p. 7

- ^ Offenbach (1874), unnumbered introductory page

- ^ Crémieux, pp. 84–92

- ^ Crémieux, pp. 10–11

- ^ Crémieux, pp. 11–12

- ^ Crémieux, pp. 15–18

- ^ Crémieux, pp. 21–22

- ^ Gänzl and Lamb, p. 278

- ^ Crémieux, p. 27

- ^ Crémieux, pp. 29–29

- ^ Crémieux, p. 29

- ^ Crémieux, pp. 30–32

- ^ Offenbach (1874) pp. 107–109

- ^ Crémieux, p. 35

- ^ Crémieux, p. 36

- ^ Crémieux, p. 37

- ^ Crémieux, pp. 44–45

- ^ Crémieux, pp. 48–52

- ^ Crémieux, pp. 53–54

- ^ Crémieux, pp. 58–60

- ^ Crémieux, pp. 65–67

- ^ Offenbach (1859), p. 73

- ^ Crémieux, pp. 68–69

- ^ Iversen, Paul A. "The Small and Great Daidala in Boiotian History", Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte, 56, no. 4 (2007), p. 381 (subscription required)

- ^ Crémieux, p. 75

- ^ Crémieux, pp. 84–88

- ^ Crémieux, pp. 89–90

- ^ Crémieux, p. 95

- ^ Crémieux, p. 96

- ^ Crémieux, p. 98

- ^ Crémieux, p. 103

- ^ Crémieux, p. 105

- ^ Crémieux, p. 106

- ^ Crémieux, p. 107

- ^ a b c d e f g h Simeone, Nigel. "No Looking Back", The Musical Times, Summer, 2002, pp. 39–41 (subscription required)

- ^ Notes to EMI LP set SLS 5175 (1979) OCLC 869200562

- ^ Faris, pp. 66–67 and 69

- ^ Offenbach-Keck, pp. 227–229.

- ^ a b Lafargue, Gustave. "Chronique musicale", Le Figaro, 10 February 1874, p. 3 (in French)

- ^ Mellers, p. 139

- ^ Hughes (1962), p. 38

- ^ Simplified version of illustration in Faris, pp. 68–69

- ^ Faris, pp. 68–69

- ^ Hadlock, pp. 167–168

- ^ Mellers, p. 141

- ^ a b Schipperges, Thomas. "Jacques Offenbach's Galop infernal from Orphée aux enfers. A Musical Analysis", International Journal of Musicology, Vol. 8 (1999), pp. 199–214 (abstract in English to article in German) (subscription required)

- ^ Hadlock, p. 164

- ^ Harding, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Cummins, Melissa. "Use of Parody Techniques in Jacques Offenbach's Opérettes", University of Kansas, 2017, p. 89. Retrieved 29 April 2019

- ^ Offenbach-Keck, pp. 87–88

- ^ Harris, Ellen T. "Bocca chiusa", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001. Retrieved 29 April 2019 (subscription required)

- ^ Schuesselin, John Christopher. "The use of the cornet in the operettas of Gilbert and Sullivan", LSU Digital Commons, 2003, p. 4

- ^ Hughes (1959), pp. 111–112

- ^ a b Offenbach-Keck, p. 7

- ^ Faris, pp. 169–170

- ^ Moreno, H. Orphée aux enfers", Le Ménestrel, 15 February 1874, p. 85 (in French); "Musical Gossip", The Athenaeum, 21 February 1874, p. 264; and "The Drama in Paris", The Era, 15 February 1874, p. 10

- ^ a b Noël and Stoullig (1888), p. 291

- ^ a b Lamb, Andrew. "Orphée aux enfers", The Musical Times, October 1980, p. 635

- ^ a b "Offenbach–Keck: Orphée aux Enfers (OEK critical edition: 1858/1874 mixed version)", Boosey & Hawkes. Retrieved 19 April 2019

- ^ a b Gammond, p. 69

- ^ Offenbach-Keck, pp. 11–17

- ^ Offenbach 1874, pp. 1–16

- ^ Notes to EMI CD set 0724355672551 (2005) OCLC 885060258

- ^ Notes to Deutsche Grammophon CD set 00028947764038 (2006) OCLC 1052692620

- ^ Notes to Chesky CD set CD-57 (2010) OCLC 767880784, Decca CD sets 00028947876311 (2009) OCLC 952341087 and 00028941147622 (1982) OCLC 946991260, and Deutsche Grammophon CD set 00028947427520 (2003) OCLC 950991848

- ^ Quoted in notes to EMI LP set SLS 5175

- ^ Quoted in Faris, pp. 69–70

- ^ Faris, pp. 69–70

- ^ Yon, p. 212

- ^ Smith, p. 350

- ^ Yon, pp. 212–213

- ^ Clément and Larousse, pp. 503–504

- ^ Munteanu Dana. "Parody of Greco-Roman Myth in Offenbach's Orfée aux enfers and La belle Hélène", Syllecta Classica 23 (2013), pp. 81 and 83–84 (subscription required)

- ^ Kracauer, p. 177

- ^ Gammond, p. 51

- ^ Senelick, p. 40

- ^ Faris, p. 176

- ^ Taruskin, p. 646

- ^ Faris, p. 77

- ^ Faris, p. 219

- ^ Obituary, The Times, 6 October 1880, p. 3

- ^ "Jacques Offenbach dead – The end of the great composer of opera bouffe" Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, 6 October 1880

- ^ Hauger, George. "Offenbach: English Obituaries and Realities", The Musical Times, October 1980, pp. 619–621 (subscription required) Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Noël and Stoullig (1888), p. 287 and (1890), p. 385; Stoullig, p. 225; and "Courrier des Spectacles", Le Gaulois: littéraire et politique, 10 May 1912, p. 1 (all in French)

- ^ Gänzl and Lamb, pp. 286, 296, 300 and 306

- ^ Grovlez, Gabriel. "Jacques Offenbach: A Centennial Sketch" Archived 9 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Musical Quarterly, July 1919, pp. 329–337

- ^ Gammond, pp. 55–56

- ^ Holland, Bernard. "A U.P.S. Man Joins Offenbach’s Gods and Goddesses" Archived 23 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 18 November 2006, p. B14

- ^ Lamb, Andrew. "Offenbach, Jacques", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001. Retrieved 26 April 2019. (subscription required) Archived 1 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gänzl, p. 1514

- ^ Hadlock, p. 162

- ^ "Music and Theatres in Paris", The Musical World, 1 September 1860, p. 552; and "Petit Journal", Le Figaro, 20 September 1860, p. 7 (in French)

- ^ Noël and Stoullig (1879), p. 354

- ^ Gammond, pp. 124–125

- ^ a b Noël and Stoullig (1879), p. 364

- ^ Yon, p. 581, and Gammond, p. 124

- ^ Noel and Stoullig (1888), p. 287

- ^ Noël and Stoullig (1890), p. 385

- ^ Stoullig, p. 225

- ^ "Courrier des Spectacles", Le Gaulois: littéraire et politique, 10 May 1912, p. 1 (in French)

- ^ "Orphée aux enfers au Théâtre Mogador", Le Figaro, 22 December 1931, p. 6 (in French)

- ^ "Orphée aux enfers", Bibliothèque nationale de France. (in French) Retrieved 26 April 2019

- ^ De Brancovan, Mihai. "La Vie Musicale" Revue des Deux Mondes, March 1988, pp. 217–218 (in French) (subscription required)

- ^ a b "Orphée aux enfers" Archived 23 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, WorldCat. Retrieved 23 April 2019. OCLC 987620990

- ^ Kasow, J. "Massis's Eurydice – report from Geneva", Opera, January 1998, pp. 101–102

- ^ a b c Gammond, p. 72

- ^ Gier, Albert. "La fortune d'Offenbach en Allemagne: Traductions, Jugements Critiques, Mises en Scène", Lied Und Populäre Kultur, 57 (2012), pp. 161–180 (in French) (subscription required)

- ^ Holloway, Ronald. "The Arts: Orpheus in the Underworld/Berlin", The Financial Times, 29 December 1983, p. 5 (subscription required)

- ^ a b Orpheus in der Unterwelt, Worldcat. Retrieved 9 May 2019. OCLC 854864814

- ^ "Orpheus in der Unterwelt" Archived 2020-10-18 at the Wayback Machine, Volksoper, Vienna. Retrieved 21 April 2019

- ^ "Orphée aux enfers", Salzburg Festival. Retrieved 21 April 2019

- ^ a b "Haymarket", The Athenaeum, 30 December 1865, p. 933

- ^ a b "The London Theatres", The Era, 18 July 1869, p. 11

- ^ a b "Princess's Theatre", The Morning Post, 23 June 1870, p. 6

- ^ a b "The Royalty", The Era, 31 December 1876, p. 12

- ^ a b "Alhambra Theatre", The London Reader, 26 May 1877, p. 76

- ^ a b "Dramatic Gossip", The Athenaeum, 23 December 1911, p. 806

- ^ a b Mason, Colin. "Jolly good fun", The Guardian, 19 May 1960, p. 11

- ^ "A Modern Orpheus", The Times, 18 May 1960, p.18; "Racy Production of Orpheus", The Times, 15 August 1961, p. 11; "Bank Holiday in Hades", The Times, 24 April 1962, p. 14; Sadie, Stanley. "Spacious Orpheus", The Times, 23 August 1968, p. 12; and Blyth, Alan. "Victory for Sadler's Wells Opera over name", The Times, 4 January 1974, p. 8

- ^ Gilbert, pp. 372–373

- ^ Hoyle, Martin. "British Opera Diary: Orpheus in the Underworld. English National Opera at the London Coliseum, May 2", Opera, July 1987, p. 184

- ^ Higgins, John. "A midsummer night's pantomime", The Times, 23 June 1992, p. 2[S]; and Milnes, Rodney. "All down to a hell of a good snigger", The Times, 22 March 1993, p. 29

- ^ Canning, Hugh. "Vulgar down below", The Sunday Times, 13 October 2019, p. 23; Maddocks, Fiona. "The week in classical", The Observer, 12 October 2019, p. 33; Morrison, Richard. "Offenbach without bite: Emma Rice's ENO debut is too earnest and not funny enough", The Times, 7 October 2019, p. 11; Jeal, Erica. "Orpheus in the Underworld", The Guardian, 6 October 2019, p. 11; Christiansen, Rupert. "Orpheus falls victim to the curse of the Coli", The Daily Telegraph, 7 October 2019, p. 24; and Hall, George, "Orpheus in the Underworld review at London Coliseum – Emma Rice's misjudged production", The Stage, 6 October 2019.

- ^ "The Opera", The Argus, 1 April 1872, p. 2

- ^ "The Miracle Revival", The New York Times, 4 April 1929, p. 23

- ^ Taubman, Howard. "Opera", The New York Times, 21 September 1956, p. 31

- ^ Dierks, Donald. "SFO has romp with 'Orpheus'", The San Diego Union, 3 August 1985 (subscription required)

- ^ Gregson, David. "'Orpheus' is infernal fun, but overdone", The San Diego Union, 17 June 1989, p. C-8 (subscription required)

- ^ "Offenbach" Archived 19 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Operabase. Retrieved 21 April 2019

- ^ "Orphée aux enfers" Archived 23 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, WorldCat. Retrieved 23 April 2019 OCLC 611370392

- ^ "Orphée aux enfers" Archived 23 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, WorldCat. Retrieved 23 April 2019 OCLC 77269752

- ^ "Orphée aux enfers" Archived 23 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, WorldCat. Retrieved 23 April 2019 OCLC 809216810

- ^ "Orpheus in the Underworld" Archived 16 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, WorldCat. Retrieved 23 April 2019. OCLC 162231323

- ^ "Orpheus in the Underworld" Archived 16 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, WorldCat. Retrieved 23 April 2019.OCLC 223103509

- ^ "Orpheus in the Underworld" Archived 16 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, WorldCat. Retrieved 23 April 2019.OCLC 973664218

- ^ "Orphée aux Enfers: sung in German" Archived 23 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, WorldCat. Retrieved 23 April 2019 OCLC 762494356

- ^ "Orpheus in der Unterwelt: buffoneske Oper in zwei Akten (vier Bildern)" Archived 23 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, WorldCat. Retrieved 23 April 2019 OCLC 938532010

- ^ "Orpheus in der Unterwelt" Archived 23 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine. WorldCat. Retrieved 23 April 2019 OCLC 854864814

- ^ "Orphée aux enfers" Archived 23 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, WorldCat. Retrieved 23 April 2019 OCLC 156744586

- ^ "Orpheus in the Underworld" Archived 23 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, WorldCat. Retrieved 23 April 2019. OCLC 742448334

- ^ WorldCat OCLC 1121483592

Sources

[edit]- Clément, Félix; Pierre Larousse (1881). Dictionnaire des opéras (Dictionnaire lyrique) (in French). Paris: Larousse. OCLC 174469639.

- Crémieux, Hector (1860). Orphée aux enfers: libretto (in French). Paris: Bourdilliat. OCLC 717856068.

- Faris, Alexander (1980). Jacques Offenbach. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-11147-3.

- Gammond, Peter (1980). Offenbach. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-0257-2.

- Gänzl, Kurt (2001). The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre (second ed.). New York: Schirmer. ISBN 978-0-02-864970-2.

- Gänzl, Kurt; Andrew Lamb (1988). Gänzl's Book of the Musical Theatre. London: The Bodley Head. OCLC 966051934.

- Gilbert, Susie (2009). Opera for Everybody. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-22493-7.

- Hadlock, Heather (2014). "Ce bal est original!: Classical Parody and Burlesque in Orphée aux Enfers". In Sabine Lichtenstein (ed.). Music's Obedient Daughter: the Opera Libretto from Source to Score. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-3808-0.

- Harding, James (1979). Folies de Paris: The Rise and Fall of French Operetta. London: Chappell. ISBN 978-0-903443-28-9.

- Hughes, Gervase (1959). The Music of Arthur Sullivan. London: Macmillan. OCLC 500626743.

- Hughes, Gervase (1962). Composers of Operetta. London: Macmillan. OCLC 868313857.

- Kracauer, Siegfried (1938). Orpheus in Paris: Offenbach and the Paris of his Time. New York: Knopf. OCLC 639465598.

- Luez, Philippe (2001). Jacques Offenbach: musicien européen (in French). Biarritz: Séguier. ISBN 978-2-84049-221-4.

- Mellers, Wilfrid (2008). The Masks of Orpheus: Seven Stages in the Story of European Music. London: Travis and Emery. ISBN 978-1-904331-73-5.

- Offenbach, Jacques (1859). Orphée aux enfers: Opéra bouffon en deux actes et quatre tableaux: vocal score (PDF) (in French). Paris: Huegel. OCLC 352348784. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-04-28. Retrieved 2019-04-28.

- Offenbach, Jacques (1874). Orphée aux enfers: Opéra-féerie en quatre actes et douze tableaux: vocal score (in French). Paris: Menestrel. OCLC 20041978.

- Offenbach, Jacques; Jean-Christophe Keck (2002). Orphée aux enfers, 1858 version: orchestral score (in French). Berlin: Boosey and Hawkes. ISBN 978-3-7931-1988-3.

- Noël, Édouard; Edmond Stoullig (1879). Les Annales du Théâtre et de la Musique, 1878 (in French). Paris: Charpentier. OCLC 983267831.

- Noël, Édouard; Edmond Stoullig (1888). Les Annales du Théâtre et de la Musique, 1887 (in French). Paris: Charpentier. OCLC 1051558946.

- Noël, Édouard; Edmond Stoullig (1890). Les Annales du Théâtre et de la Musique, 1889 (in French). Paris: Charpentier. OCLC 762327066.

- Senelick, Laurence (2017). Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87180-8.

- Smith, John (1859). "Orphée aux enfers". Revue et Gazette musicale de Paris (in French). Paris: Revue et Gazette musicale. OCLC 983118707.

- Stoullig, Edmond (1903). Les Annales du Théâtre et de la Musique, 1902 (in French). Paris: Ollendorf. OCLC 762311617.

- Taruskin, Richard (2010). The Oxford History of Western Music. 3: Music in the Nineteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-019-538483-3.

- Traubner, Richard (1997). "Jacques Offenbach". In Amanda Holden (ed.). The Penguin Opera Guide. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-051385-1.

- Traubner, Richard (2003). Operetta: A Theatrical History (second ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96641-2.

- Yon, Jean-Claude (2000). Jacques Offenbach (in French). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 978-2-07-074775-7.

External links

[edit] Media related to Orphée aux Enfers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Orphée aux Enfers at Wikimedia Commons The full text of Orphée aux Enfers at Wikisource

The full text of Orphée aux Enfers at Wikisource- "Orpheus In the Underworld" The Guide to Light Opera and Operetta

- "Orpheus in the Underworld" The Guide to Musical Theatre

- Orphée aux enfers: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Literature by and about Orpheus in the Underworld in the German National Library catalogue