Oral gospel traditions

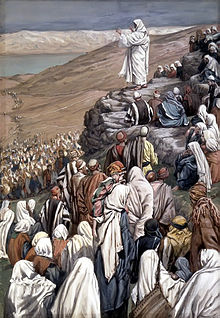

Oral gospel traditions is the hypothetical first stage in the formation of the written gospels as information was passed by word of mouth. These oral traditions included different types of stories about Jesus. For example, people told anecdotes about Jesus healing the sick and debating with his opponents. The traditions also included sayings attributed to Jesus, such as parables and teachings on various subjects which, along with other sayings, formed the oral gospel tradition.[1][2] The supposition of such traditions have been the focus of scholars such as Bart Ehrman, James Dunn, and Richard Bauckham, although each scholar varies widely in his conclusions, with Ehrman and Bauckham publicly debating on the subject.

History of research

[edit]It is widely agreed amongst Biblical scholars that accounts of Jesus's teachings and life were initially conserved by oral transmission, which was the source of the written gospels.[3] For much of the 20th Century, form criticism, pioneered by figures such as Martin Dibelius and Rudolf Bultmann, dominated Biblical scholarship.[4]

Modern media criticism began with Birger Gerhardsson, a visionary Swedish scholar who was the first to challenge the hegemony of form criticism. Gerhardsson, basing his research off of Rabbinic methods of transmission, argued that the early Christians transmitted the story and teachings of Jesus through strict memorization, claiming that a collegium formed by the twelve disciples could carefully control tradition. While rebuffed for decades, he is now viewed as a pioneer of research in oral Gospel traditions; he was a man Rafael Rodriguez said was "literally decades ahead of his time".[5]

Another seminal figure who appeared two decades later was Werner Kelber. Kelber, drawing on various fields such as communications media and cultural studies and applying them to the Bible, opposed form-critical views of a steady evolution of the Jesus traditions, arguing instead that the transition from oral tradition to the written gospels, namely the Gospel of Mark, represented a disruption of transmission. Kelber is also known for his "brilliant (if awkward) metaphor" comparing oral tradition to a "biosphere" rather than a medium; oral tradition provides a context, not just a medium, of tradition.[6] Indeed, Kelber's groundbreaking works caused what Theodore Weeden called "a paradigmatic crisis" that would reshape scholarship in the years to come.[7]

Kenneth Bailey was another scholar who made a tremendous mark on par with Kelber on the study of the Oral Gospel Traditions. First published in 1991, Bailey's essay "Informal Controlled Oral Tradition and the Synoptic Gospels" presented a model of oral tradition based on contemporary traditions in the Middle East, which Bailey gathered first-hand. Bailey argued that communities, especially by leading members, informally controlled oral traditions to a degree, preventing core parts of stories from major change. Bailey showed how oral tradition could maintain stability over time while exhibiting variance in detail.[8]

Richard Horsley was another major player in New Testament media criticism. Horsley focused on literary criticism and how societal power interacts with media criticism.[9]

Critical methods: source and form criticism

[edit]

Biblical scholars use a variety of critical methodologies known as biblical criticism. They apply source criticism to identify the written sources beneath the canonical gospels. Scholars generally understood that these written sources must have had a prehistory as oral tellings, but the very nature of oral transmission seemed to rule out the possibility of recovering them. In the early 20th century, the German scholar Hermann Gunkel demonstrated a new critical method, form criticism, which he believed could discover traces of oral tradition in written texts. Gunkel specialized in Old Testament studies, but other scholars soon adopted and adapted his methods to the study of the New Testament.[10]

The essence of form criticism is the identification of the Sitz im Leben, "situation in life", which gave rise to a particular written passage. When form critics discuss oral traditions about Jesus, they theorize about the particular social situation in which different accounts of Jesus were told.[11][12] For New Testament scholars, this focus remains the Second Temple period. First-century Palestine was predominantly an oral society.[3]

A modern consensus exists that Jesus must be understood as a Jew in a Jewish environment.[13] According to scholar Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus was so very firmly rooted in his own time and place as a first-century Palestinian Jew – with his ancient Jewish comprehension of the world and God – that he does not translate easily into a modern idiom. Ehrman stresses that Jesus was raised in a Jewish household in the Jewish hamlet of Nazareth. He was brought up in a Jewish culture, accepted Jewish ways, and eventually became a Jewish teacher who, like other Jewish teachers of his time, debated the Law of Moses orally.[14] Early Christians sustained these teachings of Jesus orally. Rabbis or teachers in every generation were raised and trained to deliver this oral tradition accurately. It consisted of two parts: the Jesus tradition (i.e., logia or sayings of Jesus) and inspired opinion. The distinction is one of authority: where the earthly Jesus has spoken on a subject, that word is to be regarded as an instruction or command.[15]

According to Bruce Chilton and Craig A. Evans, "the Judaism of the period treated such traditions very carefully, and the New Testament writers in numerous passages applied to apostolic traditions the same technical terminology found elsewhere in Judaism for 'delivering', 'receiving', 'learning', 'holding', 'keeping', and 'guarding', the traditioned 'teaching'. In this way they both identified their traditions as 'holy word' and showed their concern for a careful and ordered transmission of it. The word and work of Jesus were an important albeit distinct part of these apostolic traditions."[16]

NT Wright also argued for a stable oral tradition, stating "Communities that live in an oral culture tend to be story-telling communities [...] Such stories [...] acquire a fairly fixed form, down to precise phraseology [...] they retain that form, and phraseology, as long as they are told [...] The storyteller in such a culture has no license to invent or adapt at will. The less important the story, the more the entire community, in a process that is informal but very effective, will keep a close watch on the precise form and wording with which the story is told.[17]

According to Anthony Le Donne, "Oral cultures have been capable of tremendous competence...The oral culture in which Jesus was reared trained their brightest children to remember entire libraries of story, law, poetry, song, etcetera...When a rabbi imparted something important to his disciples, the memory was expected to maintain a high degree of stability." Le Donne disputes the view that the oral traditions are comparable to a 'Telephone Game'. [18]

According to Dunn, the accuracy of the oral gospel tradition was insured by the community designating certain learned individuals to bear the main responsibility for retaining the gospel message of Jesus. The prominence of teachers in the earliest communities such as the Jerusalem Church is best explained by the communities' reliance on them as repositories of oral tradition.[19] According to Dunn, one of the most striking features to emerge from his study is the "amazing consistency" of the history of the tradition "which gave birth to the NT".[20][21] Dunn argues that Kelber exaggerates the divide between orality and written transmission, critiquing the latter's view that Mark tried to override prior oral tradition. [22] Rafael Rodriguez also sees Kelber's media contrast as much too distinct, arguing that tradition was sustained in memory alongside text. [23] Terence Mournet argued that oral traditions provide reliable historical data as well. [24]

John Kloppenborg wrote that the variants between the Synoptic Gospels are completely explainable by literary interdependence.[25] Travis Derico, following Dunn's ideas, argues that memorization and oral transmission can potentially account for the Synoptics instead and deserves increased study.[26]

Jens Schroter argued that a mass of material from various sources, such as Christian prophets issuing sayings in the name of Jesus, the Hebrew Bible, miscellaneous sayings, alongside the actual words of Jesus, were all attributed by the Gospels to the singular historical Jesus.[27] However, James DG Dunn and Tucker Ferda point out that the early Christian tradition sought to distinguish between their own sayings and those of the historical Jesus and that there is little evidence that the claims of new "prophets" often became mistaken as those of Jesus himself; Ferda notes that the phenomena of prophetic sayings merging with those of Jesus is more relevant to the dialogue gospels of the second and third centuries.[28][29]

A review of Richard Bauckham's book Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony states "The common wisdom in the academy is that stories and sayings of Jesus circulated for decades, undergoing countless retellings and embellishments before being finally set down in writing."[30] Alan Kirk praised Bauckham for realizing the deep link between true memory and tradition, potentially contributing widely to Jesus research and the demise of form criticism, and his pioneering and underappreciated application of cognition and memory to the Jesus tradition. However, Kirk argues that Bauckham's failure to bridge the divide between eyewitness testimony and the Jesus tradition is detrimental to the overall case the two editions of Jesus and the Eyewitnesses provides against the prevailing skepticism form critics brought in. [31]

According to Bart Ehrman, the oral traditions are comparable to a "Telephone game. He says "Invariably, the story has changed so much in the process of retelling that everyone gets a good laugh...Imagine this same activity...over the expanse of the Roman empire...with thousands of participants...some of whom have to translate the stories into different languages."[32] These traditions precede the surviving gospels by decades, going back to the time of Jesus and the time of Paul's persecution of the early Christian Jews, prior to his conversion.[33]

Alan Kirk finds Ehrman's writing in Jesus Before the Gospels to cite memory research selectively, neglecting the fact that John Bartlett's experiment discovered that stories quickly took on a stable, 'schematic' form rather quickly. Ehrman also overemphasizes individual transmission instead of community, makes a 'lethal oversight' where Jan Vansina, whom he quoted as evidence for corruption in the Jesus tradition, changed his mind, arguing that information was conveyed through a community that placed controls, rather than through chains of transmission easily subject to change. Kirk does sympathize with Ehrman that appealing to memory cannot automatically guarantee historicity.[34] Both Ehrman and Bauckham overemphasize individuality, whether transmission chains or eyewitness testimony, in their studies.

According to Maurice Casey, Aramaic sources have been detected in Mark's Gospel, which could indicate use of early or even eyewitness testimony when it was being written.[35]

Oral traditions and the formation of the gospels

[edit]Modern scholars have concluded that the Canonical Gospels went through four stages in their formation:

- The first stage was oral, and included various stories about Jesus such as healing the sick, or debating with opponents, as well as parables and teachings.

- In the second stage, the oral traditions began to be written down in collections (collections of miracles, collections of sayings, etc.), while the oral traditions continued to circulate

- In the third stage, early Christians began combining the written collections and oral traditions into what might be called "proto-gospels" – hence Luke's reference to the existence of "many" earlier narratives about Jesus

- In the fourth stage, the authors of our four Gospels drew on these proto-gospels, collections, and still-circulating oral traditions to produce the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.[1]

Mark, Matthew and Luke are known as the Synoptic Gospels because they are so highly interdependent. Since the twentieth century, scholars have generally agreed that Mark was the first of the gospels to be written (see Marcan priority). The author does not seem to have used extensive written sources, but rather to have woven together small collections and individual traditions into a coherent presentation.[36] It is generally, though not universally, agreed that the authors of Matthew and Luke used as sources the gospel of Mark and a collection of sayings called the Q source. These two together account for the bulk of each of Matthew and Luke, with the remainder made up of smaller amounts of source material unique to each, called the M source for Matthew and the L source for Luke, which may have been a mix of written and oral material (see Two-source hypothesis). Most scholars believe that the author of John's gospel used oral and written sources different from those available to the Synoptic authors, although there are indications that a later editor of this gospel may have used Mark and Luke.[37]

Oral transmission may also be seen as a different approach to understanding the Synoptic Gospels in New Testament scholarship. Current theories attempt to link the three synoptic gospels together through a common textual tradition. However, many problems arise when linking these three texts together (see the Synoptic problem). This has led many scholars to hypothesize the existence of a fourth document from which Matthew and Luke drew upon independently of each other (for example, the Q source).[38] The Oral Transmission hypothesis based on the oral tradition steps away from this model, proposing instead that this common, shared tradition was transmitted orally rather than through a lost document.[39]

Elite agency

[edit]While there is a broad consensus on this view of the process of development from oral tradition to written gospels, an alternative thesis proposed by historian Robyn Faith Walsh in her book The Origins of Early Christian Literature, builds on scholarship from historian of religion Jonathan Z. Smith. She proposes viewing gospel authors as individual elite cultural producers in the classical vein, writing for an elite audience instead of early Christian communities, with agency in the composition of their text rather than primarily transmitters of tradition.[40][41]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Burkett 2002, p. 124.

- ^ Dunn 2013, pp. 3–5.

- ^ a b Dunn 2013, pp. 290–291.

- ^ Mournet, Terence (2005). Oral Tradition and Literary Dependency: Variability and Stability in the Synoptic Tradition and Q. Mohr Siebeck. p. 122. ISBN 978-3161484544.

- ^ Rodriguez, Rafael (2013). Oral Tradition and the New Testament: A Guide for the Perplexed. T&T Clark. p. 48-51. ISBN 9780567626004.

- ^ Rodriguez, Rafael (2013). Oral Tradition and the New Testament: A Guide for the Perplexed. T&T Clark. p. 51-55. ISBN 9780567626004.

- ^ Weeden, Theodore (1979). Mark: Traditions in Conflict. Fortress Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0800613716.

- ^ Rodriguez, Rafael (2013). Oral Tradition and the New Testament: A Guide for the Perplexed. T&T Clark. p. 65, 67-68. ISBN 9780567626004.

- ^ Rodriguez, Rafael (2013). Oral Tradition and the New Testament: A Guide for the Perplexed. T&T Clark. p. 69-69. ISBN 9780567626004.

- ^ Muilenburg 1969, pp. 1–18.

- ^ Casey 2010, pp. 141–143.

- ^ Ehrman 2012, p. 84.

- ^ Van Voorst 2000, p. 5.

- ^ Ehrman 2012, pp. 13, 86, 276.

- ^ Dunn 2013, pp. 19, 55.

- ^ Chilton, Bruce; Evans, Craig (1998). Authenticating the Words of Jesus & Authenticating the Activities of Jesus, Volume 2 Authenticating the Activities of Jesus. Brill. pp. 53–55. ISBN 978-9004113022.

- ^ Wright, NT. ""Five Gospels But No Gospel". Brill. 28 (2): 112-113. doi:10.1163/9789004421295_009 (inactive 1 November 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Le Donne, Anthony (2011). Historical Jesus: What Can We Know and How Can We Know It?. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0802865267.

- ^ Dunn 2013, pp. 55, 223, 279–280, 309.

- ^ Ehrman 2012, p. 117.

- ^ Dunn 2013, pp. 359–360 – "One of the most striking features to emerge from this study is the amazing consistency of the history of the NT tradition, the tradition which gave birth to the NT."

- ^ Dunn 2003, pp. 203.

- ^ Rodriguez, Rafael (2010). Structuring Early Christian Memory: Jesus in Tradition, Performance and Text. T&T Clark. p. 3-6. ISBN 978-0567264206.

- ^ Mournet, Terence (2005). Oral Tradition and Literary Dependency: Variability and Stability in the Synoptic Tradition and Q. Mohr Siebeck. p. 122. ISBN 978-3161484544.

- ^ Kloppenborg, John (2007). "Variation in the Reproduction of the Double Tradition and an Oral Q?". Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses. 83: 53-80. doi:10.2143/ETL.83.1.2021741.

- ^ Derico, Travis (2018). Oral Tradition and Synoptic Verbal Agreement: Evaluating the Empirical Evidence for Literary Dependence. Pickwick Publications, an Imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 368-369. ISBN 978-1620320907.

- ^ Horsley, Richard (2006). Performing the Gospel: Orality, Memory, and Mark. Augsburg Books. p. 104-46. ASIN B000SELH00.

- ^ Ferda, Tucker (2024). Jesus and His Promised Second Coming: Jewish Eschatology and Christian Origins. Eerdmans. p. 282. ISBN 9780802879905.

- ^ Dunn 2013, pp. 13–40.

- ^ Hahn, Scott W.; Scott, David, eds. (1 September 2007). Letter & Spirit, Volume 3: The Hermeneutic of Continuity: Christ, Kingdom, and Creation. Emmaus Road Publishing. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-931018-46-3.

- ^ Kirk, Alan (2017). "Ehrman, Bauckham and Bird on Memory and the Jesus Tradition". Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus. 15 (1): 88–114. doi:10.1163/17455197-01501004.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (1997). The New Testament. A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. Oxford University Press. p. 44.

- ^ Ehrman 2012, pp. 85.

- ^ Kirk, Alan (2017). "Ehrman, Bauckham and Bird on Memory and the Jesus Tradition". Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus. 15 (1): 88–114. doi:10.1163/17455197-01501004.

- ^ Casey 2010, p. 63-64.

- ^ Telford 2011, pp. 13–29.

- ^ Scholz 2009, pp. 166–188.

- ^ Dunn 2003, pp. 192–205.

- ^ Dunn 2003, pp. 238–252.

- ^ Walsh, Robyn Faith (28 January 2021). The Origins of Early Christian Literature: Contextualizing the New Testament. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108835305.

- ^ Crook, Zeba (2021). "Compte Rendus: The Origins of Early Christian Literature: Contextualizing the New Testament within Greco-Roman Literary Culture". Studies in Religion. 51 (2). doi:10.1177/00084298211022142 – via SageJournals.

Bibliography

[edit]- Burkett, Delbert (2002). An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00720-7.

- Casey, Maurice (2010). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-567-64517-3.

- Dunn, James D. G. (2003). Jesus Remembered: Christianity in the Making, Volume 1. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-3931-2.

- Dunn, James D. G. (2013). The Oral Gospel Tradition. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-6782-7.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2012). Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-220460-8.

- Muilenburg, James (March 1969). "Form Criticism and beyond". Journal of Biblical Literature. 88 (1): 1–18. doi:10.2307/3262829. JSTOR 3262829.

- Scholz, Daniel J. (2009). Jesus in the Gospels and Acts. St Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-955-6.

- Telford, William R. (2011). "Mark's Portrait of Jesus". In Burkett, Delbert (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Jesus. Wiley–Blackwell. pp. 13–29. ISBN 978-1-4051-9362-7.

- Van Voorst, Robert E. (2000). Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence Studying the Historical Jesus. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-4368-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Aune, David E. (2004). "Oral Tradition in the Hellenistic World". In Wansbrough, Henry (ed.). Jesus and the Oral Gospel Tradition. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-567-04090-9.

- Aune, David E. (2010). "Form Criticism". In Aune, David E. (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to The New Testament. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-1894-4.

- Bockmuehl, Markus (2004) [1994]. This Jesus: Martyr, Lord, Messiah. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-567-08296-1.

- Dunn, James D. G. (2003a). "The History of the Tradition: New Testament". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 950–71. ISBN 978-0-8028-3711-0.

- Ehrman, Bart (2005) [2003]. Lost Christianities: The Battles For Scripture And The Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518249-1.

- Hammann, Konrad (2012). Rudolf Bultmann – Eine Biographie. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-152013-6.

- Kelber, Werner H. (1983). The oral and the written Gospel: the hermeneutics of speaking and writing in the synoptic tradition, Mark, Paul, and Q. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21097-5.

- Wansbrough, Henry (2004) [1991]. "Introduction". In Wansbrough, Henry (ed.). Jesus and the Oral Gospel Tradition. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-567-04090-9.