Operculum (brain)

| Operculum (brain) | |

|---|---|

Operculum | |

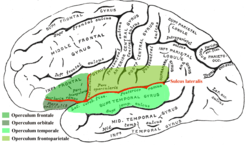

Parietal operculum (green), temporal operculum (blue), and insular cortex (brown), with red inset showing the position of the brain slice. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | operculum frontale, operculum parietale, operculum temporale |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

In human brain anatomy, an operculum (Latin, meaning "little lid") (pl.: opercula), may refer to the frontal, temporal, or parietal operculum, which together cover the insula as the opercula of insula.[1] It can also refer to the occipital operculum, part of the occipital lobe.

The insular lobe is a portion of the cerebral cortex that has invaginated to lie deep within the lateral sulcus. It sits like an island (the meaning of insular) almost surrounded by the groove of the circular sulcus and covered over and obscured by the insular opercula.

A part of the parietal lobe, the frontoparietal operculum, covers the upper part of the insular lobe from the front to the back.[2] The opercula lie on the precentral and postcentral gyri (on either side of the central sulcus).[3] The part of the parietal operculum that forms the ceiling of the lateral sulcus functions as the secondary somatosensory cortex.

Development

[edit]Normally, the insular opercula begin to develop between the 20th and the 22nd weeks of pregnancy. At weeks 14 to 16 of fetal development, the insula begins to invaginate from the surface of the immature cerebrum of the brain, until at full term, the opercula completely cover the insula.[4] This process is called opercularization.[5]

Case reports

[edit]Albert Einstein's brain

[edit]Opinions differ on whether Albert Einstein's brain possessed parietal opercula. Falk, et al. claim that the brain actually did have parietal opercula,[6] while Witelson et al. claim that it did not.[7]

Einstein's lower parietal lobe (which is involved in mathematical thought, visuospatial cognition and imagery of movement) was 15% larger than average.[8]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Dorland 2012, p. 1328

- ^ Dorland 2012, p. 1327

- ^ Joseph M. Tonkonogy; Antonio E. Puente (23 January 2009). Localization of Clinical Syndromes in Neuropsychology and Neuroscience. Springer Publishing Company. p. 392. ISBN 978-0-8261-1967-4. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ Larroche JC (1977). "Development of the central nervous system". Developmental Pathology of the Neonate. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica. pp. 319–27. ISBN 978-90-219-2107-5., as cited in note 3 of Chen CY, Zimmerman RA, Faro S, et al. (August 1996). "MR of the cerebral operculum: abnormal opercular formation in infants and children". American Journal of Neuroradiology. 17 (7): 1303–11. PMID 8871716.

- ^ Cheng-Yu Chen, Robert A. Zimmerman, Scott Faro, Beth Parrish, Zhiyue Wang, Larissa T. Bilaniuk, Ting-Ywan Chou. MR of the Cerebral Operculum. AJNR 16:1677–1687, Sep 1995 0195-6108/95/1608–1677 American Society of Neuroradiology

- ^ Falk, Lepore & Noe 2013, p. 22

- ^ Witelson SF, Kigar DL, Harvey T (June 1999). "The exceptional brain of Albert Einstein". Lancet. 353 (9170): 2149–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10327-6. PMID 10382713.

- ^ Witelson's measurement

References

[edit]- Dorland (2012). Dorlands Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- Falk D, Lepore FE, Noe A (April 2013). "The cerebral cortex of Albert Einstein: a description and preliminary analysis of unpublished photographs". Brain. 136 (Pt 4): 1304–27. doi:10.1093/brain/aws295. PMC 3613708. PMID 23161163.