Safety

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2010) |

Safety is the state of being "safe", the condition of being protected from harm or other danger. Safety can also refer to the control of recognized hazards in order to achieve an acceptable level of risk.

Meanings

The word 'safety' entered the English language in the 14th century.[1] It is derived from Latin salvus, meaning uninjured, in good health, safe.[2]

There are two slightly different meanings of "safety". For example, "home safety" may indicate a building's ability to protect against external harm events (such as weather, home invasion, etc.), or may indicate that its internal installations (such as appliances, stairs, etc.) are safe (not dangerous or harmful) for its inhabitants.

Discussions of safety often include mention of related terms. Security is such a term. With time the definitions between these two have often become interchanged, equated, and frequently appear juxtaposed in the same sentence. Readers are left to conclude whether they comprise a redundancy. This confuses the uniqueness that should be reserved for each by itself. When seen as unique, as we intend here, each term will assume its rightful place in influencing and being influenced by the other.

Safety is the condition of a "steady state" of an organization or place doing what it is supposed to do. "What it is supposed to do" is defined in terms of public codes and standards, associated architectural and engineering designs, corporate vision and mission statements, and operational plans and personnel policies. For any organization, place, or function, large or small, safety is a normative concept. It complies with situation-specific definitions of what is expected and acceptable.[3]

Using this definition, protection from a home's external threats and protection from its internal structural and equipment failures (see Meanings, above) are not two types of safety but rather two aspects of a home's steady state.

In the world of everyday affairs, not all goes as planned. Some entity's steady state is challenged. This is where security science, which is of more recent date, enters. Drawing from the definition of safety, then:

Security is the process or means, physical or human, of delaying, preventing, and otherwise protecting against external or internal, defects, dangers, loss, criminals, and other individuals or actions that threaten, hinder or destroy an organization’s "steady state," and deprive it of its intended purpose for being.

Using this generic definition of safety it is possible to specify the elements of a security program.[3]

Limitations

Safety can be limited in relation to some guarantee or a standard of insurance to the quality and unharmful function of an object or organization. It is used in order to ensure that the object or organization will do only what it is meant to do.

It is important to realize that safety is relative. Eliminating all risk, if even possible, would be extremely difficult and very expensive. A safe situation is one where risks of injury or property damage are low and manageable.

When something is called safe, this usually means that it is safe within certain reasonable limits and parameters. For example, a medication may be safe, for most people, under most circumstances, if taken in a certain amount.

A choice motivated by safety may have other, unsafe consequences. For example, frail elderly people are sometimes moved out of their homes and into hospitals or skilled nursing homes with the claim that this will improve the person's safety. The safety provided is that daily medications will be supervised, the person will not need to engage in some potentially risky activities such as climbing stairs or cooking, and if the person falls down, someone there will be able to help the person get back up. However, the end result might be decidedly unsafe, including the dangers of transfer trauma, hospital delirium, elder abuse, hospital-acquired infections, depression, anxiety, and even a desire to die.[4]

Types

There is a distinction between products that meet standards, that are safe, and that merely feel safe. The highway safety community uses these terms:[citation needed]

Normative

Normative safety is achieved when a product or design meets applicable standards and practices for design and construction or manufacture, regardless of the product's actual safety history.

Substantive

Substantive or objective safety occurs when the real-world safety history is favorable, whether or not standards are met.

Perceived

Perceived or subjective safety refers to the users' level of comfort and perception of risk, without consideration of standards or safety history. For example, traffic signals are perceived as safe, yet under some circumstances, they can increase traffic crashes at an intersection. Traffic roundabouts have a generally favorable safety record[5] yet often make drivers nervous.

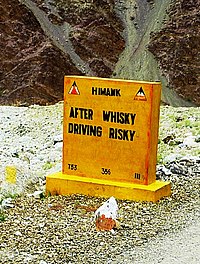

Low perceived safety can have costs. For example, after the 9/11 attacks in 2001, many people chose to drive rather than fly, despite the fact that, even counting terrorist attacks, flying is safer than driving. Perceived risk discourages people from walking and bicycling for transportation, enjoyment or exercise, even though the health benefits outweigh the risk of injury.[6]

Perceived safety can drive regulation which increases costs and inconvenience without improving actual safety.[7][8]

Security

Also called social safety or public safety, security addresses the risk of harm due to intentional criminal acts such as assault, burglary or vandalism.

Because of the moral issues involved, security is of higher importance to many people than substantive safety. For example, a death due to murder is considered worse than a death in a car crash, even though in many countries, traffic deaths are more common than homicides.

Operational safety

Operational safety is the absence of unacceptable risk in the presence of the associated hazards that are known, expected, or reasonably assumed to exist during a planned activity and any likely contingencies associated with it.[9]

This section needs expansion with: Define operational safety. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . (August 2024) |

Risks and responses

Safety is generally interpreted as implying a real and significant impact on risk of death, injury or damage to property. In response to perceived risks many interventions may be proposed with engineering responses and regulation being two of the most common.

Probably the most common individual response to perceived safety issues is insurance, which compensates for or provides restitution in the case of damage or loss.

System safety and reliability engineering

System safety and reliability engineering is an engineering discipline. Continuous changes in technology, environmental regulation and public safety concerns make the analysis of complex safety-critical systems more and more demanding.

A common fallacy, for example among electrical engineers regarding structure power systems, is that safety issues can be readily deduced. In fact, safety issues have been discovered one by one, over more than a century in the case mentioned, in the work of many thousands of practitioners, and cannot be deduced by a single individual over a few decades. A knowledge of the literature, the standards and custom in a field is a critical part of safety engineering. A combination of theory and track record of practices is involved, and track record indicates some of the areas of theory that are relevant. (In the US, persons with a state license in Professional Engineering in Electrical Engineering are expected to be competent in this regard, the foregoing notwithstanding, but most electrical engineers have no need of the license for their work.)

Safety is often seen as one of a group of related disciplines: quality, reliability, availability, maintainability and safety. (Availability is sometimes not mentioned, on the principle that it is a simple function of reliability and maintainability.) These issues tend to determine the value of any work, and deficits in any of these areas are considered to result in a cost, beyond the cost of addressing the area in the first place; good management is then expected to minimize total cost.

Measures

Safety measures are activities and precautions taken to improve safety, i.e. reduce risk related to human health. Common safety measures include:

- Chemical analysis

- Destructive testing of samples

- Drug testing of employees, etc.

- Examination of activities by specialists to minimize physical stress or increase productivity

- Geological surveys to determine whether land or water sources are polluted, how firm the ground is at a potential building site, etc.

- Government regulation so suppliers know what standards their product is expected to meet.

- Industry regulation so suppliers know what level of quality is expected. Industry regulation is often imposed to avoid potential government regulation.

- Instruction manuals explaining how to use a product or perform an activity

- Instructional videos demonstrating proper use of products

- Root cause analysis to identify causes of a system failure and correct deficiencies.

- Internet safety or online safety, is protection of the user's safety from cyber threats or computer crime in general.

- Periodic evaluations of employees, departments, etc.

- Physical examinations to determine whether a person has a physical condition that would create a problem.

- Process safety management is an analytical tool focused on preventing and managing releases of hazardous materials in industrial plants.

- Safety margins/safety factors, for instance, a product rated to never be required to handle more than 100 kg might be designed to fail under at least 200 kg, a safety factor of two. Higher numbers are used in more sensitive applications such as medical or transit safety.

- Self-imposed regulation of various types.

- Implementation of standard protocols and procedures so that activities are conducted in a known way.

- Statements of ethics by industry organizations or an individual company so its employees know what is expected of them.

- Stress testing subjects a person or product to stresses in excess of those the person or product is designed to handle, to determining the "breaking point".

- Training of employees, vendors, product users

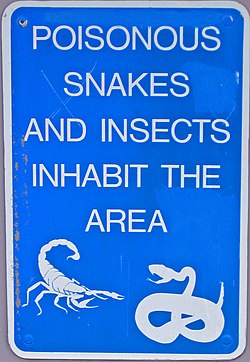

- Visual examination for dangerous situations such as emergency exits blocked because they are being used as storage areas.

- Visual examination for flaws such as cracks, peeling, loose connections.

- X-ray analysis to see inside a sealed object such as a weld, a cement wall or an airplane outer skin.

Research

Today there are multiple scientific journals focusing on safety research. Among the most popular ones are Safety Science and Journal of Safety Research.[10][11]

The goal of this research is to identify, understand, and mitigate risks to human health and well-being in various environments. This involves systematically studying hazards, analyzing potential and actual accidents, and developing effective strategies to prevent injuries and fatalities. Safety research aims to create safer products, systems, and practices by incorporating scientific, engineering, and behavioral insights. Ultimately, it seeks to enhance public safety, reduce economic losses, and improve overall quality of life by ensuring that both individuals and communities are better protected from harm.[12]

Standards organizations

A number of standards organizations exist that promulgate safety standards. These may be voluntary organizations or government agencies. These agencies first define the safety standards, which they publish in the form of codes. They are also Accreditation Bodies and entitle independent third parties such as testing and certification agencies to inspect and ensure compliance to the standards they defined. For instance, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) formulated a certain number of safety standards in its Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code (BPVC) and accredited TÜV Rheinland to provide certification services to guarantee product compliance to the defined safety regulations.[13]

United States

American National Standards Institute

A major American standards organization is the American National Standards Institute (ANSI). Usually, members of a particular industry will voluntarily form a committee to study safety issues and propose standards. Those standards are then recommended to ANSI, which reviews and adopts them. Many government regulations require that products sold or used must comply with a particular ANSI standard.

Government agencies

Many government agencies set safety standards for matters under their jurisdiction, such as:

- the Food and Drug Administration

- the Consumer Product Safety Commission

- the United States Environmental Protection Agency

Testing laboratories

Product safety testing, for the United States, is largely controlled by the Consumer Product Safety Commission. In addition, workplace related products come under the jurisdiction of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), which certifies independent testing companies as Nationally Recognized Testing Laboratories (NRTL), see.[14]

European Union

Institutions

- the European Commission (EC)

- the European Committee for Standardization (CEN)

- the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)

- the European Safety Federation (ESF)

Testing laboratories

The European Commission provides the legal framework, but the different Member States may authorize test laboratories to carry out safety testing.

Other countries

Standards institutions

- British Standards Institution

- Canadian Standards Association

- Deutsches Institut für Normung

- International Organization for Standardization

- Standards Australia

Testing laboratories

Many countries have national organizations that have accreditation to test and/or submit test reports for safety certification. These are typically referred to as a Notified or Competent Body.

See also

- Accident – Unforeseen event, often with a negative outcome

- Behavior-based safety – System used in industry to reduce exposure to hazards

- Risk management – Identification, evaluation and control of risks

- Safety statement – Document that outlines how a company manages their health and safety

- Certified safety professional – Qualified safety personnel

- American Society of Safety Professionals – Professional organization

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – United States government public health agency CDC

- Poison control center – Medical service that provides over-the-phone advice on poison exposure

- Safety in Australia

- Natural disaster – Type of adverse event

- Seismic analysis – Study of the response of buildings and structures to earthquakes

- Crowd control – Public security practice

- Aisles: Safety and regulatory considerations – Architectural element

- Consumer product safety – Request to return a product after the discovery of safety issues or product defects

- Door-related accidents – Movable barrier that allows ingress and egress

- Explosives safety – Safety practices related to explosives

- Gun safety – Study and practice of safe operation of firearms

- Child safety

- Child safety seat – Seat designed to protect children during traffic collisions

- Toy safety – Practice of ensuring that toys meet safety standards

- Safe Kids Worldwide – Global non-profit organization working to prevent childhood injury

- Patient safety – Prevention, reduction, reporting, and analysis of medical error

- Sports injury – Physical and emotional trauma safety

- Electrical safety

- Electrical safety testing – Testing to ensure the compliance of electrical systems with safety standards

- Arc flash – Heat and light produced during an electrical arc fault

- Fire safety – Practices to reduce the results of fire

- Process safety – Study, prevention, and management of major hazardous material accidents in process plants

- Nuclear safety and security – Regulations for uses of radioactive materials

- Lists of nuclear disasters and radioactive incidents

- Criticality accident – Uncontrolled nuclear fission chain reaction

- Transportation

- Road

- Automotive safety – Study and practice to minimize the occurrence and consequences of motor vehicle accidents

- Road traffic safety – Methods and measures for reducing the risk of death and injury on roads

- Motorcycle safety – Study of the risks and dangers of motorcycling

- Bicycle safety – Safety practices to reduce risk associated with cycling

- Traffic collision – Incident when a vehicle collides with another object

- Pedestrian safety – Methods and measures for reducing the risk of death and injury on roads

- Rail

- Maritime

- Maritime safety – Safety around maritime activities

- Sailing ship accidents – Naval mishaps

- Aircraft

- Aviation safety – State in which risks associated with aviation are at an acceptable level

- Aviation accidents and incidents – Accidental aviation occurences

- Road

- Occupational safety and health – Field concerned with the safety, health and welfare of people at work

- Work accident – Occurrence during work that leads to physical or mental harm

- Personal protective equipment – Equipment designed to help protect an individual from hazards

- Safety data sheet – Sheet listing work-related hazards of a product or substance

- Security – Degree of resistance to, or protection from, harm

- Security company – Type of company

- Safety engineering – Engineering discipline which assures that engineered systems provide acceptable levels of safety

- Fail-safe – Design feature or practice

- Poka-yoke – Process that helps an equipment operator avoid mistakes

- Software system safety

References

- ^ Safety Definition & Meaning - Merriam-Webster

- ^ safety | Etymology of safety by etymonline

- ^ a b Charles G. Oakes, PhD, Blue Ember Technologies, LLC."Safety versus Security in Fire Protection Planning Archived 2012-03-13 at the Wayback Machine,"The American Institute of Architects: Knowledge Communities, May 2009. Retrieved on June 22, 2011.

- ^ Neumann, Ann (February 2019). "Going to Extremes". Harper's Magazine. ISSN 0017-789X. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- ^ "Proven Safety Countermeasures: Roundabouts". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on 2012-07-31. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ^ Jeroen Johan de Hartog; Hanna Boogaard; Hans Nijland; Gerard Hoek (1 August 2010). "Do the Health Benefits of Cycling Outweigh the Risks?". Environmental Health Perspectives. 118 (8): 1109–1116. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901747. PMC 2920084. PMID 20587380.

- ^ Stotz, Tamara; Bearth, Angela; Ghelfi, Signe Maria; Siegrist, Michael (May 2022). "The perceived costs and benefits that drive the acceptability of risk-based security screenings at airports". Journal of Air Transport Management. 100: 102183. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2022.102183. hdl:20.500.11850/531027.

- ^ Buchan, John C.; Thiel, Cassandra L.; Steyn, Annalien; Somner, John; Venkatesh, Rengaraj; Burton, Matthew J.; Ramke, Jacqeline (June 2022). "Addressing the environmental sustainability of eye health-care delivery: a scoping review". The Lancet Planetary Health. 6 (6): e524–e534. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00074-2. PMID 35709809.

- ^ "Operational safety definition". www.lawinsider.com. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "Scopus preview - Scopus - Safety Science". www.scopus.com. Retrieved 2024-05-19.

- ^ "Scopus preview - Scopus - Journal of Safety Research". www.scopus.com. Retrieved 2024-05-19.

- ^ "Aims and scope - Safety Science | ScienceDirect.com by Elsevier". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2024-05-19.

- ^ Rheinland, TÜV. "Pressure Vessel Inspection According to ASME". tuv.com. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "Nationally Recognized Testing Laboratories (NRTLs) - Occupational Safety and Health Administration". www.osha.gov. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

Further reading

- Wildavsky, Aaron; Wildavsky, Adam (2008). "Risk and Safety". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.