Pelvic fracture

| Pelvic fracture | |

|---|---|

| |

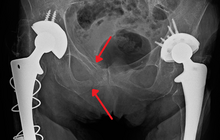

| A pelvic X-ray showing an open book fracture | |

| Symptoms | Pelvic pain, particularly with movement[1] |

| Complications | Internal bleeding, bladder injury, vaginal trauma[2][3] |

| Types | Stable, unstable[1] |

| Causes | Falls, motor vehicle collisions, vehicle hitting a pedestrian, crush injury[2] |

| Risk factors | Osteoporosis[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, confirmed by X-rays or CT scan[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Femur fracture, vertebral fracture, low back pain[4] |

| Treatment | Bleeding control (pelvic binder, angiographic embolization, preperitoneal packing), fluid replacement[2] |

| Medication | Pain medication[1] |

| Prognosis | Stable: Good[1] Unstable: Risk of death ~15%[2] |

| Frequency | 3% of adult fractures[1] |

A pelvic fracture is a break of the bony structure of the pelvis.[1] This includes any break of the sacrum, hip bones (ischium, pubis, ilium), or tailbone.[1] Symptoms include pain, particularly with movement.[1] Complications may include internal bleeding, injury to the bladder, or vaginal trauma.[2][3]

Common causes include falls, motor vehicle collisions, a vehicle hitting a pedestrian, or a direct crush injury.[2] In younger people significant trauma is typically required while in older people less significant trauma can result in a fracture.[1] They are divided into two types: stable and unstable.[1] Unstable fractures are further divided into anterior posterior compression, lateral compression, vertical shear, and combined mechanism fractures.[2][1] Diagnosis is suspected based on symptoms and examination with confirmation by X-rays or CT scan.[1] If a person is fully awake and has no pain of the pelvis medical imaging is not needed.[2]

Emergency treatment generally follows advanced trauma life support.[2] This begins with efforts to stop bleeding and replace fluids.[2] Bleeding control may be achieved by using a pelvic binder or bed-sheet to support the pelvis.[2] Other efforts may include angiographic embolization or preperitoneal packing.[2] After stabilization, the pelvis may require surgical reconstruction.[2]

Pelvic fractures make up around 3% of adult fractures.[1] Stable fractures generally have a good outcome.[1] The risk of death with an unstable fracture is about 15%, while those who also have low blood pressure have a risk of death approaching 50%.[2][4] Unstable fractures are often associated with injuries to other parts of the body.[3]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Symptoms include pain, particularly with movement.[1]

Complications

[edit]Complications are likely to result in cases of excess blood loss or puncture to certain organs, possibly leading to shock.[5][6] Swelling and bruising may result, more so in high-impact injuries.[6] Pain in the affected areas may differ where severity of impact increases its likelihood and may radiate if symptoms are aggravated when one moves around.[citation needed]

Causes

[edit]Common causes include falls, motor vehicle collisions, a vehicle hitting a pedestrian, or a direct crush injury.[2] In younger people significant trauma is typically required while in older people less significant trauma can result in a fracture.[1]

Pathophysiology

[edit]The bony pelvis consists of the ilium (i.e., iliac wings), ischium, and pubis, which form an anatomic ring with the sacrum. Disruption of this ring requires significant energy. When it comes to the stability and the structure of the pelvis, or pelvic girdle, understanding its function as support for the trunk and legs helps to recognize the effect a pelvic fracture has on someone.[7] The pubic bone, the ischium and the ilium make up the pelvic girdle, fused together as one unit. They attach to both sides of the spine and circle around to create a ring and sockets to place hip joints. Attachment to the spine is important to direct force into the trunk from the legs as movement occurs, extending to one's back. This requires the pelvis to be strong enough to withstand pressure and energy. Various muscles play important roles in pelvic stability. Because of the forces involved, pelvic fractures frequently involve injury to organs contained within the bony pelvis. In addition, trauma to extra-pelvic organs is common. Pelvic fractures are often associated with severe hemorrhage due to the extensive blood supply to the region. The veins of the presacral pelvic plexus are particularly vulnerable. Greater than 85 percent of bleeding due to pelvic fractures is venous or from the open surfaces of the bone.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

[edit]If a person is fully awake and has no pain in the pelvis, medical imaging of the pelvis is not needed.[2]

Classification

[edit]

Pelvic fractures are most commonly described using one of two classification systems. The different forces on the pelvis result in different fractures. Sometimes they are determined based on stability or instability.[8]

Tile classification

[edit]The Tile classification system is based on the integrity of the posterior sacroiliac complex.[citation needed]

In type A injuries, the sacroiliac complex is intact. The pelvic ring has a stable fracture that can be managed nonoperatively. Type B injuries are caused by either external or internal rotational forces resulting in partial disruption of the posterior sacroiliac complex. These are often unstable. Type C injuries are characterized by complete disruption of the posterior sacroiliac complex and are both rotationally and vertically unstable. These injuries are the result of great force, usually from a motor vehicle crash, fall from a height or severe compression.[citation needed]

Young-Burgess classification

[edit]

The Young-Burgess classification system is based on mechanism of injury: anteroposterior compression type I, II and III, lateral compression types I, II and III, and vertical shear,[5] or a combination of forces.

Lateral compression (LC) fractures involve transverse fractures of the pubic rami, either ipsilateral or contralateral to a posterior injury.

- Grade I – Associated sacral compression on side of impact

- Grade II – Associated posterior iliac ("crescent") fracture on side of impact

- Grade III – Associated contralateral sacroiliac joint injury

The most common force type, lateral compression (LC) forces, from side-impact automobile accidents and pedestrian injuries, can result in an internal rotation.[9] The superior and inferior pubic rami may fracture anteriorly, for example. Injuries from shear forces, like falls from above, can result in disruption of ligaments or bones. When multiple forces occur, it is called combined mechanical injury (CMI). The best imaging modality to use for this classification is probably a pelvic CT scan.[10]

Open book fracture

[edit]One specific kind of pelvic fracture is known as an 'open book' fracture. This is often the result of a heavy impact to the groin (pubis), a common motorcycling accident injury. In this kind of injury, the left and right halves of the pelvis are separated at front and rear, the front opening more than the rear, i.e. like an open book that falls to the ground and splits in the middle. Depending on the severity, this may require surgical reconstruction before rehabilitation.[11] Forces from an anterior or posterior direction, like head-on car accidents, usually cause external rotation of the hemipelvis, an “open-book” injury. Open fractures have an increased risk of infection and hemorrhaging from vessel injury, leading to higher mortality.[12]

Prevention

[edit]As the human body ages, the bones become weaker and brittle and are therefore more susceptible to fractures. Certain precautions are crucial in order to lower the risk of getting pelvic fractures. The most damaging is one from a car accident, cycling accident, or falling from a high building which can result in a high energy injury.[13] This can be very dangerous because the pelvis supports many internal organs and can damage these organs. Falling is one of the most common causes of pelvic fracture. Therefore, proper precautions should be taken to prevent this from happening.[citation needed]

Treatment

[edit]A pelvic fracture is often complicated and treatment can be a long and painful process. Depending on the severity, pelvic fractures can be treated with or without surgery.[14]

Initial

[edit]A high index of suspicion should be held for pelvic injuries in anyone with major trauma. The pelvis should be stabilized with a pelvic binder.[15] This can be a purpose-made device, but improvised pelvic binders have also been used around the world to good effect.[16] Stabilisation of the pelvic ring reduces blood loss from the pelvic vessels and reduced the risk of death.

Surgery

[edit]Surgery is often required for pelvic fractures. Many methods of pelvic stabilization are used including external fixation or internal fixation and traction.[17][18] There are often other injuries associated with a pelvic fracture so the type of surgery involved must be thoroughly planned.[19]

Rehabilitation

[edit]Pelvic fractures that are treatable without surgery are treated with bed rest. Once the fracture has healed enough, rehabilitation can be started with first standing upright with the help of a physical therapist, followed by starting to walk using a walker and eventually progressing to a cane.[citation needed]

Prognosis

[edit]Mortality rates in people with pelvic fractures are between 10 and 16 percent.[20] However, death is typically due to associated trauma affecting other organs, such as the brain. Death rates due to complications directly related to pelvic fractures, such as bleeding, are relatively low.[20]

Epidemiology

[edit]In the United States of America, about 10 percent of people that seek treatment at a level 1 trauma center after a blunt force injury have a pelvic fracture.[20] Motorcycle injuries are the most common cause of pelvic fractures, followed by injuries to pedestrians caused by motor vehicles, large falls (over 15 feet), and motor vehicle crashes.[20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Pelvic Fractures". OrthoInfo - AAOS. February 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p ATLS - Advanced Trauma Life Support - Student Course Manual (10 ed.). American College of Surgeons. 2018. pp. 89, 96–97. ISBN 9780996826235.

- ^ a b c Peitzman, Andrew B.; Rhodes, Michael; Schwab, C. William (2008). The Trauma Manual: Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 322. ISBN 9780781762755.

- ^ a b Walls, Ron; Hockberger, Robert; Gausche-Hill, Marianne (2017). Rosen's Emergency Medicine - Concepts and Clinical Practice E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 577, 588. ISBN 9780323390163.

- ^ a b Walker, J (Nov 9–15, 2011). "Pelvic fractures: classification and nursing management". Nursing Standard. 26 (10): 49–57, quiz 58. doi:10.7748/ns2011.11.26.10.49.c8816. PMID 22206172.

- ^ a b "Fracture of the Pelvis". OrthoInfo. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

- ^ Dimon, Theodore Jr. (2010). The body in motion : its evolution and design. Berkeley, Calif.: North Atlantic Books. pp. 49–56. ISBN 978-1556439704.

- ^ Young, JW; Resnik, CS (December 1990). "Fracture of the Pelvis: Current Concepts of Classification". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 155 (6): 1169–75. doi:10.2214/ajr.155.6.2122661. PMID 2122661.

- ^ Lee, C; Porter, K (February 2007). "The prehospital management of pelvic fractures". Emergency Medicine Journal. 24 (2): 130–3. doi:10.1136/emj.2006.041384. PMC 2658194. PMID 17251627.

- ^ "Pelvic Fractures". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "Anteroposterior Compression Fracture of Pelvis (Open Book Fracture)". Elsevier: Netter's Images.

- ^ Rothenberger, D; Velasco, R; Strate, R; Fischer, RP; Perry JF, Jr. (March 1978). "Open pelvic fracture: a lethal injury". The Journal of Trauma. 18 (3): 184–7. doi:10.1097/00005373-197803000-00006. PMID 642044.

- ^ "High Energy Fractures". International Society for Fracture Repair. Archived from the original on 2013-01-27.

- ^ Davis DD, Foris LA, Kane SM, et al. (January 2021). "Pelvic Fracture". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. PMID 28613485. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ "The Ideal Pelvic Binder". www.trauma.org. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Mallinson, T (2013). "Alternative improvised pelvic binder". African Journal of Emergency Medicine. 3 (4): 195–6. doi:10.1016/j.afjem.2013.04.006.

- ^ Mirghasemi A, Mohamadi A, Ara AM, Gabaran NR, Sadat MM (2009). "Completely displaced S-1/S-2 growth plate fracture in an adolescent: case report and review of literature". J Orthop Trauma. 23 (10): 734–8. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181a23d8b. PMID 19858983. S2CID 6651435.

- ^ Taguchi, T; Kawai, S; Kaneko, K; Yugue, D (1999). "Operative management of displaced fractures of the sacrum". Journal of Orthopaedic Science. 4 (5): 347–52. doi:10.1007/s007760050115. PMID 10542038. S2CID 46282760.

- ^ Hancharenka, V.; Tuzikov, A.; Arkhipau, V.; Kryvanos, A. (March 2009). "Preoperative planning of pelvic and lower limbs surgery by CT image processing". Pattern Recognition and Image Analysis. 19 (1): 109–113. doi:10.1134/S1054661809010209. S2CID 34590414.

- ^ a b c d Vincent, Jean-Louis (2011). Textbook of Critical Care (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. p. 1523. ISBN 9781437713671.