Oneida Nation of the Thames

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2008) |

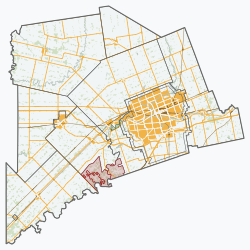

Oneida 41 | |

|---|---|

| Oneida Indian Reserve No. 41 | |

| Coordinates: 42°49′N 81°24′W / 42.817°N 81.400°W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| County | Middlesex |

| First Nation | Oneidas of the Thames |

| Settled | 1840 |

| Government | |

| • Chief | J. Todd Cornelius |

| • Federal riding | Lambton—Kent—Middlesex |

| • Prov. riding | Lambton—Kent—Middlesex |

| Area | |

| • Land | 22.16 km2 (8.56 sq mi) |

| Population (September, 2018)[2] | |

• Total | 2,175 |

| • Density | 57.8/km2 (150/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Postal Code | N0L |

| Area code(s) | 519 and 226 |

| Website | www.oneida.on.ca |

The Oneida Nation of the Thames is an Onyota'a:ka (Oneida) First Nations band government located in southwestern Ontario, located about a 30-minute drive from London, Ontario, Canada.[3] The Oneida Nation reports a total of 6,108 members, including 2,159 residents.[4]

The Oneida Settlement

[edit]The Oneida, Haudenosaunee people, an Iroquoian speaking people, had a traditional territory that once covered a large section of the eastern part of North America. The territory of the Oneida Settlement is part of the traditional hunting area known as the Beaver Hunting Grounds, which was recognized in 1701 Nanfan Treaty. The people who live there are descendants of many later migrants, a small group of assimilated/Christian Oneidas who relocated to Southwold, Ontario, Canada from New York state in 1840. The original settlers of the Oneida community were associated with two Christian denominations, Methodist and Anglican. One of the leaders in the migration was an ordained Methodist minister. Soon after their arrival in Ontario, the settlers built Methodist and Anglican churches. Since those early days, these two churches have had over half of the population as members. By 1877, some people began to join the Baptists. Old Methodist records show some families and individuals shifting from the Methodist to the Baptist church, and the reverse.

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada designates the settlement as Oneida 41 Indian Reserve or simply as Oneida 41.[5] The Oneida people who live or are descendants of people at the "Oneida Settlement" always insist that their lands be called a "settlement" because Oneida people purchased the relocation lands in Ontario. This is a distinction from having the lands "set aside" or "reserved" for them. Many other lands inhabited by indigenous people in North America are called "Indian reserves".

Prior to selling their New York lands, the Oneida requested assurance from the Crown that should they remove to Canada, they would be protected and treated in every respect as their brethren who had always resided within the precincts of the province. Having received such assurance, they sold their lands in New York and selected the Thames River tract. They expressed a wish that their tenure to these lands should be precisely the same as that held by the resident tribes; the parties from whom the lands were purchased should surrender them to Her Majesty in trust for the sole use and benefit of the tribe and their posterity. In this way, the people of the Oneida Settlement would be put on a footing with other tribes in the province, and be exempt from the taxation to which the non-native inhabitants of the country were liable by law.

The circumstances of purchase and subsequent surrender of the land have led some present-day Oneidas to hold an equivocal position regarding the status of the communal lands. A number of Oneidas object to the term “reserve” in reference to the Oneida community. They prefer to call it the “Oneida Settlement” or "Oneida Community", claiming that the land is private property, having been purchased by their ancestors rather than given by treaty. They also contend that the Oneida have never surrendered the land to the Crown, therefore the government should not have jurisdiction over them. Nevertheless, the government treats Oneida as a reserve. The Oneidas recognize, though often with protest, this de facto status of the community. Those who claim the land is still privately owned rather than held in trust do not press to establish this claim with the government.

Several reasons are stated for letting the issue ride: the impossibility of getting all the special interest groups in the community to work together to prove their claim; lack of funds to fight such a case; and fear of losing certain advantages which reserve status owes them (Indian Act Governments). This latter is perhaps the most important reason. Those who deny that Oneida is Crown land held in trust for the Indians, fear that should the government accept their claim to its being privately owned land, then the Oneida might have to pay taxes. These would be delinquent since 1840.

Governance

[edit]The current Indian Act Band Council consists of Chief Randall Phillips and twelve (12) councillors: Carol Antone,[4] Clinton Cornelius, Brandon Doxtator, Charity Doxtator, Gloria Doxtator, H.Grant Doxtator, Harry Doxtator, Kathleen Doxtator, Ursula Doxtator and Olive Elm, Justin Kechego-Doxtator and Stacey Phillips. The council, in turn, is a member of the Southern First Nation Secretariat, a Regional Chiefs' Council. On a larger political scale, the First Nation is a member of the Association of Iroquois and Allied Indians, a Tribal Political Organization representing eight Iroquoian and Anishinaabe First Nation governments in Ontario.

This community also has a hereditary government structure in place.

Women Chiefs at Oneida Nation of the Thames

[edit]Virginia Summers was the 1st elected chief at Oneida Nation of the Thames (1963?). Susan John was acting chief at some point after Virginia Summers. Sheri Doxtator, turtle clan, was elected in 2014. Jessica Hill was elected in 2018.

Sheri Doxtator during her term practiced a consensus decision-making to the council. She was able to convene several joint traditional council and elected council meetings that were open for all members of Oneida to attend. She actively sought to work with the clan mothers and faith keepers on issues of importance to the community including wellbeing, community wellness, and local economy. Doxtator, along with Chief White-Eye of Chippewas of the Thames First Nation and Chief Rogers of Munsee-Delaware First Nation supported tri-council discussions between the three communities.

Community

[edit]The community contains three sub-divisions, a community centre, and three parks. Bingo and radio bingo are very popular, and sports are important. The people attend longhouse and the annual ceremonies. They teach the Oneida language to all children in school.

The Community Centre has been the centre of controversy related to its construction, funding, and operations. Envisioned as a central facility for community use, it was envisioned to be self-sustaining by renting meeting rooms for special events (e.g., birthday parties and other celebrations). Without a strong revenue base, the Community Centre has always operated in a deficit position.

Language Revitalization

[edit]In 2015, the Oneida Language and Cultural Centre celebrated the opening of a new building. With the centre's help, Marsha and Max Ireland have been working on an Oneida sign language guidebook as part of a pilot project working with elected councillor Olive Elm and master speaker in 2018.

Facilities

[edit]The Oneida people who live in this reserve also have a traditional longhouse and government. There are two factions: the River Road Longhouse follows the Code of Handsome Lake as well as the Great Law.

A number of Oneida own independent businesses, including several craft shops, variety stores, gas bars, and a great number of smoke shops. Two elementary schools have been built: Standing Stone and The Log School (Tsi ni yu kwali ho:tu')'. A health clinic is located in downtown Oneida. This area includes a community-owned radio station, administration building, senior rest home, a volunteer fire hall/ambulance station, water treatment facility, sewage treatment facilities, public works building, community centre, police station, and a training centre.

Annual events

[edit]The Oneida Nation of the Thames holds an annual Oneida Fair, the third weekend in the month of September. The Oneida Fair was once an occasion for the people to celebrate and compete in agricultural events and other competitions associated with their historical rural lifestyle.

Today most Oneida people do not rely on an agricultural lifestyle. Their lives do not depend on a rural garden, home canning, baking, sewing, arts and crafts, and the raising of livestock. They have become more urbanized just as have other populations in Canada. But, people do participate every year and enter the various agricultural and home arts competitions, albeit on a smaller scale than in the past. Since the early 21st century, the Oneida Fairboard has sponsored a fireworks show at the Fair. It also has featured musicians such as Joanne Shenendoah (Oneida Indian Tribe of New York) and local acts such as Robbie Antone (blues performer).

The Oneida Fair has likely gained more importance for those members who no longer live at the settlement. It is an occasion for homecoming and a chance to renew tribal ties. Many people feel welcome at the fair because it is generally a secular and non-political event.

Neighbours

[edit]The closest tribal or First Nation neighbours to the Oneida are the Munsee-Delaware Nation and the Chippewas of the Thames.

Recent successes

[edit]In the summer of 2007, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care approved the Oneida Nation of the Thames for the licensing and funding of 64 long-term care beds, as well as $2.8 million in capital. The First Nation continues to negotiate with other governments and partners to participate in this opportunity for family care. The facility will employ 70-80 people and will bring in 70 million dollars over a 20-year span. It will also allow First Nations people to return to their families, and partake in cultural activities.

Media

[edit]A First Nations/community radio station in Oneida Nation of the Thames operates at 89.5 FM. This unlicensed station is branded as Oneida Radio 89.5 FM The Eagle[6] or Eagle Radio 89.5, etc. and has no call sign.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Oneida 41 community profile". 2011 Census data. Statistics Canada. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ Branch, Government of Canada; Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada; Communications (3 November 2008). "Oneida Nation of the Thames". Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. Government of Canada. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ^ a b "Oneida Nation of the Thames – Oneida Nation of the Thames". oneida.on.ca. Retrieved 2016-08-27.

- ^ Indian and Northern Affairs Canada Reserve/Settlement/Village Detail

- ^ Oneida Radio 89.5 FM The Eagle