Grim Fandango

| Grim Fandango | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | LucasArts[a] |

| Publisher(s) | LucasArts[b] |

| Director(s) | Tim Schafer |

| Programmer(s) | Bret Mogilefsky |

| Artist(s) | Peter Tsacle |

| Writer(s) | Tim Schafer |

| Composer(s) | Peter McConnell |

| Engine | GrimE |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Graphic adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Grim Fandango is a 1998 adventure game directed by Tim Schafer and developed and published by LucasArts for Microsoft Windows. It is the first adventure game by LucasArts to use 3D computer graphics overlaid on pre-rendered static backgrounds. As with other LucasArts adventure games, the player must converse with characters and examine, collect, and use objects to solve puzzles.

Grim Fandango is set in the Land of the Dead and the retro-futuristic version of the 1950s, through which recently departed souls, represented as calaca-like figures, travel before they reach their final destination. The story follows travel agent Manuel "Manny" Calavera as he attempts to save new arrival Mercedes "Meche" Colomar, a virtuous soul, on her journey. The game combines elements of the Aztec afterlife with film noir style, with influences including The Maltese Falcon, On the Waterfront and Casablanca.

Grim Fandango received praise for its art design and direction. It was selected for several awards and is often listed as one of the greatest video games of all time. However, it was a commercial failure and contributed towards LucasArts' decision to end adventure game development and the decline of the adventure game genre.

In 2014, with help from Sony, Schafer's studio Double Fine Productions acquired the Grim Fandango license following Disney's acquisition and closure of LucasArts as a video game developer the previous year. Double Fine produced a remastered version of the game, featuring improved character graphics, controls (including point and click), an orchestrated score, and directors' commentary. It was released for Linux, OS X, PlayStation 4, PlayStation Vita, and Windows in January 2015, for Android and iOS in May 2015, for Nintendo Switch in November 2018, and for Xbox One in October 2020.

Gameplay

[edit]Grim Fandango is an adventure game, in which the player controls Manuel "Manny" Calavera (calavera being Spanish for 'skull') as he follows Mercedes "Meche" Colomar in the Underworld. The game uses the GrimE engine, pre-rendering static backgrounds from 3D models, while the main objects and characters are animated in 3D.[1] Additionally, cutscenes in the game have also been pre-rendered in 3D. The player controls Manny's movements and actions with a keyboard, a joystick, or a gamepad. The remastered edition allows control via a mouse as well. Manny must collect objects that can be used with either other collectible objects, parts of the scenery, or with other people in the Land of the Dead in order to solve puzzles and progress in the game. The game lacks any type of HUD. Unlike the earlier 2D LucasArts games, the player is informed of objects or persons of interest not by text floating on the screen when the player passes a cursor over them, but instead by the fact that Manny will turn his head toward that object or person as he walks by.[2] The player reviews the inventory of items that Manny has collected by watching him pull each item in and out of his coat jacket.[3] Manny can engage in dialogue with other characters through conversation trees to gain hints of what needs to be done to solve the puzzles or to progress the plot.[4] As in most LucasArts adventure games, the player can never die or otherwise get into a no-win situation (that prevents completion of the game).[5]

Synopsis

[edit]Setting

[edit]Grim Fandango takes place in the Land of the Dead (the Eighth Underworld), where recently departed souls aim to make their way to the Land of Eternal Rest (the Ninth Underworld) on the Four Year Journey of the Soul. Good deeds in life are rewarded by access to better travel packages, provided by the Department of Death, to assist in making the journey (such as sports cars and luxury ocean cruises), the best of which is the Number Nine, an express train that takes four minutes to reach the gate to the Ninth Underworld.[6] However, souls who did not lead a kind life are left to travel through the Land of the Dead on foot, which would take around four years. Such souls often lose faith in the existence of the Ninth Underworld and instead find jobs and stay in the Land of the Dead. The travel agents of the Department of Death act as the Grim Reaper to escort the souls from the Land of the Living to the Land of the Dead, and then determine which mode of transport the soul has merited. Each year on the Day of the Dead, these souls are allowed to visit their families in the Land of the Living.[4][7]

The souls in the Land of the Dead appear as skeletal calaca figures.[7] Alongside them are demons that have been summoned to help with the more mundane tasks of day-to-day life, such as vehicle maintenance and even drink service. The souls themselves can suffer death-within-death by being "sprouted", the result of being shot with "sproutella"-filled darts that cause flowers to grow out through bones,[8] rapidly feeding off the calcium of the soul's skeleton. The ones who are sprouted are reincarnated. Many of the characters are Mexican and occasional Spanish words are interspersed into the English dialogue, resulting in Spanglish.[2] Many of the characters smoke, following a film noir tradition;[4] the manual asks players to consider that every smoker in the game is dead.[4]

Plot

[edit]

The game is divided into four acts, each taking place on November 2 (the Day of the Dead) in four consecutive years.[9]

Manuel "Manny" Calavera is a travel agent at the Department of Death in the city of El Marrow, forced into his job to work off a debt "to the powers that be".[10] Manny is frustrated with being assigned clients that must take the four-year journey due to their poor living choices and is threatened to be fired by his boss, Don Copal, if he does not come up with better clients. Manny steals a client, Mercedes "Meche" Colomar, from his successful co-worker Domino Hurley. The Department computers assign Meche to the four-year journey even though Manny believes she should have a guaranteed spot on the "Number Nine" luxury express train due to her pureness of heart in her life.[11] When Manny went to his boss while asking Meche to wait for him fixing the issue, Meche starts her journey on foot herself. Don Copal uses it as a reason to arrest Manny. Manny was freed from arrest and sprouting by Salvador "Sal" Limones, the leader of the small underground organization the Lost Souls Alliance (LSA), who warns him of Domino and Don rigging the system to deny many clients Double N tickets, hoarding them for the boss of the criminal underworld, Hector LeMans.[12] LeMans then sells the tickets at an exorbitant price to those that can afford it. Sal recruits Manny to help LSA by setting up a system of pigeon mail and providing the group with biometrics of Manny in order to access the computer systems of the Department. Manny recognizes that he cannot stop Hector at present and instead, with the help of his driver and speed demon Glottis, he tries to find Meche on her journey in the nearby Petrified Forest. Manny arrives at the small port city of Rubacava and finds that he has beaten Meche there, and waits for her to arrive.

A year passes, and the city of Rubacava has grown. Manny now runs his own nightclub off a converted automat near the edge of the Forest. Manny sees Meche leaving the port with Domino, but when he tries to stop them, he himself was stopped by Meche. Manny learns from Olivia Ofrenda, the owner of the beatnik Blue Casket nightclub, that Don has been sprouted for letting the scandal be known.

Manny gives chase, manages to get on a board of leaving ship as a janitor, and a year later (after being promoted to a captain) tracks them to a coral mining plant on the Edge of the World. Domino has been holding Meche there as a trap to lure Manny.[13] All of Domino's clients who had their tickets stolen are also being held there and used as slave labor, both to make a profit with the coral mining and as a way to keep Hector's scandal quiet. Domino tries to convince Manny to take over his position in the plant seeing as he has no alternative and can spend the rest of eternity with Meche but he refuses. After rescuing Meche, Manny defeats Domino by causing him to fall into a rock crusher. Manny, along with Meche, Glottis and a few of the souls being held at the plant then escape from the Edge of the World.

The three travel for another year until they reach the terminus for the Number Nine train before the Ninth Underworld. The Gate Keeper to the Ninth Underworld won't let the souls progress without their tickets, mistakenly believing they have sold them, and it's further revealed that a wicked soul that has either not paid off their debt or tried to cheat the Gate Keeper with a fake or stolen Double N Ticket to gain entrance to the Ninth Underworld will cause the express train to transform into the hell train (which sends all souls on board to hell). Meanwhile, Glottis has fallen deathly ill. Manny learns from demons stationed at the terminus that the only way to revive Glottis is to travel at high speeds to restore Glottis' purpose for being summoned. Manny and the others devise a makeshift fuel source to create a "rocket" train cart, quickly taking Manny and Meche back to Rubacava and saving Glottis' life.[14] The three return to El Marrow, now found to be fully in Hector's control and renamed as Nuevo Marrow. Manny regroups with Sal and his expanded LSA and with the help of Olivia, who volunteered to join the gang earlier in Rubacava, and is able to learn about Hector's current activities.[15] Further investigation reveals that Hector not only has been hoarding the Number Nine tickets, but has created counterfeit versions that he has sold to others while keeping the real tickets for himself in a desperate attempt to balance out his sinful life and get out of the Land of the Dead.[16] Manny tries to confront Hector but is lured into another trap by Olivia, who is revealed to be Hector's girlfriend, who has also captured Sal, and is taken to Hector's greenhouse to be sprouted. Manny is able to defeat Hector after Sal sacrifices himself to prevent Olivia from interfering.

Manny and Meche are able to find the real Double N tickets, including the one that Meche should have received. Manny makes sure the rest of the tickets are given to their rightful owners; in turn, he is granted his own ticket for his good deeds.[17] Together, Manny and Meche board the Number Nine for their happy journey to the Ninth Underworld while Glottis waves tearfully goodbye.[18]

Development

[edit]Background and project inception

[edit]

Grim Fandango's development was led by project leader Tim Schafer, co-designer of Day of the Tentacle and creator of Full Throttle and the more recent Psychonauts and Brütal Legend.[19][20] Schafer had conceived a Day of the Dead-themed adventure before production of Full Throttle began,[21] and he submitted both concepts to LucasArts for approval at the same time. Full Throttle was accepted instead because of its greater mainstream appeal; it became a hit and opened the way for Schafer to create Grim Fandango.[22] Rogue Leaders: The Story of LucasArts noted that the pitching process for Grim Fandango was "a breeze" because of Schafer's earlier success, despite the new project's unusual theme.[23]

Development began soon after the completion of Full Throttle in June 1995.[21] Grim Fandango was an attempt by LucasArts to rejuvenate the graphic adventure genre, in decline by 1998.[24][25] In response to complaints that Full Throttle was too short, Schafer set the goal of having twice as many puzzles as Full Throttle, which demanded a more lengthy and ambitious story to accommodate them.[26] According to Schafer, the game was developed on a $3 million budget.[27] It was the first LucasArts adventure since Labyrinth not to use the SCUMM engine, instead using the Sith engine, pioneered by Jedi Knight: Dark Forces II, as the basis of the new GrimE engine.[28][29] The GrimE engine was built using the scripting language Lua. This design decision was due to LucasArts programmer Bret Mogilefsky's interest in the language, and is considered one of the first uses of Lua in gaming applications. The game's success led to the language's use in many other games and applications, including Escape from Monkey Island and Baldur's Gate.[30]

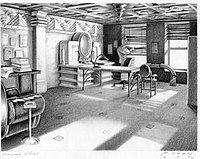

3D design

[edit]Grim Fandango mixed static pre-rendered background images with 3D characters and objects. Part of this decision was based on how the calaca figures would appear in three dimensions.[8] There were more than 90 sets and 50 characters in the game to be created and rendered; Manny's character alone comprised 250 polygons.[8] The development team found that by utilizing three-dimensional models to pre-render the backgrounds, they could alter the camera shot to achieve more effective or dramatic angles for certain scenes simply by re-rendering the background, instead of having to have an artist redraw the background for a traditional 2D adventure game.[8] The team adapted the engine to allow Manny's head to move separately from his body to make the player aware of important objects nearby.[8] The 3D engine also aided in the choreography between the spoken dialog and body and arm movements of the characters.[8][26] Additionally, full motion video cutscenes were incorporated to advance the plot, using the same in-game style for the characters and backgrounds to make them nearly indistinguishable from the actual game.[31]

Themes and influences

[edit]The game combines several Aztec beliefs of the afterlife and underworld with 1930s Art Deco design motifs and a dark plot reminiscent of the film noir genre.[32] The Aztec motifs of the game were influenced by Schafer's decade-long fascination with folklore, stemming from an anthropology class he took at University of California Berkeley, and talks with folklorist Alan Dundes, with Schafer recognizing that the four-year journey of the soul in the afterlife would set the stage for an adventure game.[2][33][34] Schafer stated that once he had set on the Afterlife setting: "Then I thought, what role would a person want to play in a Day of the Dead scenario? You'd want to be the grim reaper himself. That's how Manny got his job. Then I imagined him picking up people in the land of the living and bringing them to the land of the dead, like he's really just a glorified limo or taxi driver. So the idea came of Manny having this really mundane job that looks glamorous because he has the robe and the scythe, but really, he's just punching the clock".[2] Schafer recounted a Mexican folklore about how the dead were buried with two bags of gold to be used in the afterlife, one on their chest and one hidden in their coffin, such that if the spirits in the afterlife stole the one on the chest, they would still have the hidden bag of gold; this idea of a criminal element in the afterlife led to the idea of a crime-ridden, film noir style to the world.[35][34] The division of the game into four years was a way of breaking the game's overall puzzle into four discrete sections.[2][8][34] Each year was divided into several non-linear branches of puzzles that all had to be solved before the player could progress to the next year.[34][36]

Schafer opted to give the conversation-heavy game the flavor of film noir set in the 1930s and 1940s, stating that "there's something that I feel is really honest about the way people talked that's different than modern movies".[40] He was partially inspired by novels written by Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett.[40] Several film noir movies were also inspiration for much of the game's plot and characters. Tim Schafer stated that the true inspiration was drawn from films like Double Indemnity, in which a weak and undistinguished insurance salesman finds himself entangled in a murder plot.[32] The design and early plot are fashioned after films such as Chinatown and Glengarry Glen Ross.[2][34][7] Several scenes in Grim Fandango are directly inspired by the genre's films such as The Maltese Falcon, The Third Man, Key Largo, and most notably Casablanca: two characters in the game's second act are directly modeled after the roles played by Peter Lorre and Claude Rains in the film.[1][32] The main villain, Hector LeMans, was designed to resemble Sydney Greenstreet's character of Signor Ferrari from Casablanca.[2] His voice was also modeled after Greenstreet, complete with his trademark chuckle.

Visually, the game drew inspiration from various sources: the skeletal character designs were based largely on the calaca figures used in Mexican Day of the Dead festivities, while the architecture ranged from Art Deco skyscrapers to an Aztec temple.[32] The team turned to LucasArts artist Peter Chan to create the calaca figures. The art of Ed "Big Daddy" Roth was used as inspiration for the designs of the hot rods and the demon characters like Glottis.[2]

Originally, Schafer had come up with the name "Deeds of the Dead" for the game's title, as he had originally planned Manny to be a real estate agent in the Land of the Dead. Other potential titles included "The Long Siesta" and "Dirt Nap", before he came up with the title Grim Fandango.[40]

Voice cast

[edit]

The game featured a large cast for voice acting in the game's dialog and cutscenes, employing many Latino actors to help with the Spanish slang.[2] Voice actors included Tony Plana as Manny, Maria Canals-Barrera as Meche, Alan Blumenfeld as Glottis, and Jim Ward as Hector. Schafer credits Plana for helping to deepen the character of Manny, as the voice actor was a native Spanish speaker and suggested alternate dialog for the game that was more natural for casual Spanish conversations.[40] Schafer planned from the beginning for the voice cast to consist entirely of Latino performers.[26]

Original release

[edit]Originally, the game was to be shipped in the first half of 1998 but was delayed;[8] as a result, the game was shipped on October 28, 1998,[41] for release on October 30, the Friday before November 2, the actual date of the Day of the Dead celebration.[2] Even with the delay, the team had to drop several of the puzzles and characters from the game, including a climactic five-step puzzle against Hector LeMans at the conclusion of the game; Schafer later noted that they would have needed one to two more years to implement their original designs.[36]

Remastered version

[edit]Acquisition of rights and announcement

[edit]A remastered version of Grim Fandango was released for Linux, OS X, PlayStation 4, PlayStation Vita, and Windows platforms on January 27, 2015.[42][43][44][45] The PlayStation 4 and PlayStation Vita versions feature cross-buy[46] and cross-save.[47] It was later released for Android and iOS on May 5.[48] The remastered version was released as a PlayStation Plus title for the month of January 2016.[49][50]

The remastered version was predicated on the transition of LucasArts from a developer and publisher into a licensor and publisher in 2013 shortly after its acquisition by Disney. Under new management, LucasArts licensed several of its intellectual properties (IP), including Grim Fandango, to outside developers. Schafer was able to acquire the rights to the game with financial assistance from Sony, and started the process of building out the remaster within Double Fine Productions.[35] Schafer said that the sale of LucasArts to Disney had reminded them of the past efforts of former LucasArts president Darrell Rodriguez to release the older LucasArts titles as Legacy Properties, such as the 2009 rerelease of The Secret of Monkey Island.[40] Schafer also noted that they had tried to acquire the property from LucasArts in the years prior, but the frequent change in management stalled progress.[51] When they began to inquire about the rights with Disney and LucasArts following its acquisition, they found that Sony, through their vice president of publisher and developer relations Adam Boyes, was also looking to acquire the rights. Boyes stated that Sony had been interested in working with a wide array of developers for the PlayStation 4, and was also inspired to seek Grim Fandango's after seeing developers like Capcom and Midway Games revive older properties. Boyes' determination was supported by John Vignocchi, VP of Production for Disney Interactive, who also shared memories of the game, and was able to bring in contacts to track down the game's assets.[51] After discovering they were vying for the same property, Schafer and Boyes agreed to work together to acquire the IP and subsequent funding, planning to make the re-release a remastered version.[40][51] Sony did not ask for any of IP rights for the game, instead only asking Double Fine to give the PlayStation platforms console exclusivity in exchange for funding support, similar to their Pub Fund scheme they use to support independent developers.[51]

Challenges

[edit]

A major complication in remastering the original work was having many of the critical game files go missing or on archaic formats. A large number of backup files were made on Digital Linear Tape (DLT) which Disney/LucasArts had been able to recover for Double Fine, but the company had no drives to read the tapes. Former LucasArts sound engineer Jory Prum had managed to save a DLT drive and was able to extract all of the game's audio development data from the tapes.[51]

Schafer noted at the time of Grim Fandango's original development, retention of code was not as rigorous as present-day standards, and in some cases, Schafer believes the only copies of some files were unintentionally taken by employees when they had left LucasArts. As such, Schafer and his team have been going back through past employee records to try to trace down any of them and ask for any files they may have saved.[52] In other cases, they have had difficulty in identifying elements on the low-resolution artwork of the original game, such as an emblem on one character's hat, and have had to go looking for original concept art to figure out the design.[52]

Once original assets were identified, as to be used to present the "classic" look of the game in the Remastered edition, Double Fine worked to improve the overall look for modern computers. The textures and lighting models for the characters were improved, in particular for Manny.[51] Schafer has likened the remastering approach to The Criterion Collection film releases in providing a high-fidelity version of the game without changing the story or the characters.[53]

In addition to his own developers, Schafer reached out to players who had created unofficial patches and graphical improvements on the original game, and modifications needed to keep it running in ResidualVM, and gained their help to improve the game's assets for the remastered version.[35][54][55] One such feature was a modified control scheme that converted the game's movement controls from the tank controls to a point and click-style interface. Schafer said the team used tank controls as it was popular with other games like Resident Evil at the time, but recognized it did not work well within the adventure game genre.[40] Schafer contacted Tobias Pfaff who created the point-and-click modification to obtain access to his code to incorporate into the remastered version.[52]

Later development and new features

[edit]Double Fine demonstrated an in-progress version of the remastered game at IndieCade event in October 2014; new features included higher-resolution textures and improved resolution for the character models as well as having real-time lighting models, and the ability to switch back and forth between this presentation and the original graphics at the touch of a control. The remastered game runs in 4:3 aspect ratio but has an option to stretch this to a 16:9 ratio rather than render in a native 4:3 ratio. The remaster includes improvements to the control scheme developed by Pfaff's patch and other alternate control schemes in addition to the original tank like controls, including analogue controls for console versions and point-and-click controls for computer versions. The game's soundtrack was fully orchestrated through performances of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra (who also performed the soundtrack for Double Fine's Broken Age). The remastered version also includes developer commentary, which can be activated via the options menu and listened to at various points in the game. The PlayStation version also features cloud saving between the PS4 and Vita versions.[56] A Nintendo Switch port[57] was released on November 1, 2018.[58] Double Fine was acquired by Xbox Game Studios in 2019, and Grim Fandango for the Xbox One arrived in 2020.[59]

Soundtrack

[edit]Original soundtrack

[edit]Grim Fandango has an original soundtrack that combines orchestral score, South American folk music, jazz, bebop, swing, and big band music,[34][61] inspired by the likes of Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman as well as film composers Max Steiner and Adolph Deutsch.[62] It also has various influences from traditional Russian, Celtic, Mexican, Spanish, and Indian strings culture.[63][61] It was composed and produced by Peter McConnell at LucasArts. Others credited are Jeff Kliment (Engineer, Mixed By, Mastered), and Hans Christian Reumschüssel (Additional Music Production).[4] The score featured live musicians that McConnell knew or made contact with in San Francisco's Mission District, including a mariachi band.[62] The soundtrack was released as a CD in 1998.[64]

The soundtrack was very well received. IGN called it a "beautiful soundtrack that you'll find yourself listening to even after you're done with the game".[65] SEMO said "the compositions and performances are so good that listening to this album on a stand-alone basis can make people feel like they're in a bar back then".[66] RPGFan said "the pieces are beautifully composed, wonderfully played ... has a stellar soundtrack with music that easily stands alone outside the context of the game. This CD was an absolute pleasure to listen to and comes highly recommended".[67] Game Revolution in its game review praised as one of the "most memorable soundtracks ever to grace the inside of a cranial cavity where an eardrum used to be".[68] PC Gamer in its 2014 list of Top 100 Games, acclaimed Grim Fandango for including "one of the best soundtracks in PC gaming history".[69] In 2017 Fact magazine also listed it as one of the "100 best video game soundtracks of all time".[61]

In 1999's Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences' Interactive Achievement Awards, the soundtrack was nominated in the category of "Outstanding Achievement in Sound and Music".[70] It was also lauded by GameSpot, which awarded it the "Best PC Music awards",[71] and included it in the "Ten Best PC Game Soundtracks" list in 1999.[72]

Remastered soundtrack

[edit]After the original Pro Tools sound files were recovered, Peter McConnell found that some of the samples he had used originally did not sound good, and the team opted to re-orchestrate the score.[51] The game's soundtrack was fully orchestrated through performances of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra for the remastered version of the game.[56]

The re-made soundtrack was produced under Nile Rodgers' label Sumthing Else.[73] It had a standard release of 37 tracks, as well as a Director's Cut with 14 extra tracks (the latter sold exclusively through Sumthing Else).[74] It included the original score from the LucasArts archives, new compositions by Peter McConnell and new orchestral arrangements, as well as new extended versions of jazz pieces re-mixed at Sony Computer Entertainment America.[73]

In 2018, celebrating the 20th anniversary of the original release of the game, the soundtrack was released for the first time in vinyl format.[75]

Reception

[edit]Reviews

[edit]| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | 94/100[76] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Adventure Gamers | |

| AllGame | |

| Edge | 9/10[79] |

| GameRevolution | A−[68] |

| GameSpot | 9.3/10[80] |

| IGN | 9.4/10[60] |

| Next Generation | |

| PC Gamer (US) | 91%[76] |

| PC Zone | 9.0/10[82] |

Grim Fandango gained critical acclaim upon its release.[83] Aggregating review website Metacritic gave the game a score of 94/100.[76] Critics lauded the art direction in particular, with GameSpot rating the visual design as "consistently great".[80] PC Zone emphasized the production as a whole calling the direction, costumes, characters, music, and atmosphere expertly done. They also commented the game would make a "superb film".[82] The San Francisco Chronicle stated "Grim Fandango feels like a wild dance through a cartoonish film-noir adventure. Its wacky characters, seductive puzzle-filled plot and a nearly invisible interface allow players to lose themselves in the game just as cinemagoers might get lost in a movie."[2] The Houston Chronicle, in naming Grim Fandango the best game of 1998 along with Half-Life, complimented the graphics calling them "jaw-dropping" and commented that the game "is full of both dark and light humor".[84] IGN summed its review up by saying the game was the "best adventure game" it had ever seen.[60]

Next Generation reviewed the PC version of the game, rating it five stars out of five, and stated that "Grim Fandango is a smart, beautiful, and enjoyable adventure game that will leave you holding your breath waiting for Grim Fandango 2."[81]

The game also received criticisms from the media. Several reviewers noted that there were difficulties experienced with the interface, requiring a certain learning curve to get used to, and selected camera angles for some puzzles were poorly chosen.[60][77][80] The use of elevators in the game was particularly noted as troublesome.[60][80] The review from Adventure Gamers expressed dislike of the soundtrack, and, at times, "found it too heavy and not well suited to the game's theme".[77] A Computer and Video Games review also noted that the game had continuous and long data loading from the CD-ROM that interrupted the game and "spoils the fluidity of some sequences and causes niggling delays".[85]

In 1999, Next Generation listed Grim Fandango as number 26 on their "Top 50 Games of All Time", commenting that, "Grim offered adventure fans funny, touching, and infuriating moments in following its characters, and it did so through a magnificently beautiful game."[86]

Awards

[edit]Grim Fandango won several awards after its release in 1998. PC Gamer selected the game as the 1998 "Adventure Game of the Year".[87][88] The game won IGN's "Best Adventure Game of the Year" in 1998,[89] while GameSpot awarded it their "Best of E3 1998",[90] "PC Adventure Game of the Year",[91] "PC Game of the Year",[92] "Best PC Graphics for Artistic Design",[93] and "Best PC Music awards".[71] GameSpot named Grim Fandango its Game of the Year for 1998,[94] and in the following year included the game in their "Ten Best PC Game Soundtracks"[72] and was selected as the 10th "Best PC Ending" by their readership.[95] In 1999, Grim Fandango won "PC Adventure Game of the Year"[96][97] during the AIAS' 2nd Annual Interactive Achievement Awards (now known as the D.I.C.E. Awards); it was also nominated for "Game of the Year", "Computer Entertainment Title of the Year", "Outstanding Achievement in Art/Graphics", "Outstanding Achievement in Character or Story Development", and "Outstanding Achievement in Sound and Music".[98][99]

Grim Fandango has been included in several publishers' "Top Games" lists well after its release. GameSpot inducted the game into their "Greatest Games of All Time" in 2003 citing, "Ask just about anyone who has played Grim Fandango, and he or she will agree that it's one of the greatest games of all time."[100] GameSpy also added the game to their Hall of Fame in 2004,[101] further describing it as the seventh "Most Underrated Game of All Time" in 2003.[102] Adventure Gamers listed Grim Fandango as the seventh "Top Adventure Game of All Time" in 2004;[103] in their 2011 list of "Top 100 All-Time Adventures" it was listed as #1.[104] In 2007, IGN included the game in the "Top 25 PC Games" (as 15th)[105] and "Top 100 Games of All Time" (at 36th), citing that "LucasArts' second-to-last stab at the classic adventure genre may very well be the most original and brilliant one ever made."[106] Grim Fandango remained as the 20th in the Top 25 PC Games in IGN's 2009 list.[107]

Lists of awards and rankings

[edit]| Publication or ceremony | Award name | Result | Year | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC Gamer | Adventure Game of the Year | Won | 1998 | [87][88] |

| IGN | Best Adventure Game of the Year | Won | 1998 | [89] |

| CNET Gamecenter | Best Adventure Game of 1998 | Won | 1998 | [108] |

| GameSpot | PC Adventure Game of the Year | Won | 1998 | [91] |

| PC Game of the Year | Won | 1998 | [92] | |

| Best PC Graphics for Artistic Design | Won | 1998 | [93] | |

| Best PC Music awards | Won | 1998 | [71] | |

| Game of the Year | Won | 1998 | [94] | |

| Best of E3 1998 | Won | 1998 | [90] | |

| Computer Gaming World | Best Adventure Game of the Year | Won, tied with Sanitarium | 1998 | [109] |

| Micromanía | Best game in the Adventure and RPG categories | Won | 1998 | [110] |

| Game Critics Awards | Best Action/Adventure Game (displayed at E3) | Won | 1998 | [111] |

| Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences | PC Adventure Game of the Year | Won | 1999 | [96][97] |

| Game of the Year | Nominated | 1999 | [98] | |

| Computer Entertainment Title of the Year | Nominated | 1999 | [112] | |

| Outstanding Achievement in Art/Graphics | Nominated | 1999 | [99] | |

| Outstanding Achievement in Character or Story Development | Nominated | 1999 | [99] | |

| Outstanding Achievement in Sound and Music | Nominated | 1999 | [99] |

| Publication | Ranking name | Position | Year | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GameSpot | Ten Best PC Game Soundtracks | Included in top ten | 1999 | [72] |

| Adventure Classic Gaming | Top 10 adventure games of all time | 9th position | 2000 | [113] |

| Computer Gaming World | CGW's Hall of Fame | Inducted | 2001 | [114] |

| GameSpot | Greatest Games of All Time | Included in the list | 2003 | [100] |

| GameSpy | 25 Most Underrated Games of All Time | 7th position | 2004 | [102] |

| Adventure Gamers | Top Adventure Game of All Time | 7th position | 2004 | [103] |

| GameSpy | GameSpy Hall of Fame | Inducted | 2004 | [101] |

| IGN | Top 100 Games of All Time | 36th position | 2007 | [106] |

| IGN | Top 25 PC Games of All Time | 15th position | 2007 | [115] |

| IGN | Top 25 PC Games | 20th position | 2009 | [107] |

| Adventure Gamers | Top 100 All-Time Adventures | 1st position | 2011 | [104] |

| PC Gamer | The 100 best PC games of all time | 80th position | 2011 | [116] |

| Time | All-Time 100 Greatest Video Games | Included in list | 2012 | [117] |

| GameSpot | Best PC Ending (of all time) | 10th position | 2012 | [95] |

| Wired | The Most Jaw-Dropping Game Graphics of the Last 20 Years | Best of 1998 | 2013 | [118] |

| Empire | The 100 Greatest Video Games of All Time | 84th position | 2014 | [119] |

| PC Gamer | The PC Gamer Top 100 | 21st position | 2014 | [69] |

Sales and aftermath

[edit]Initial estimates suggested that Grim Fandango sold well during the 1998 holiday season.[120] It debuted at #6 for the first week of November on PC Data's computer game sales charts, at an average retail price of $35. It was absent by its second week.[121] In the United Kingdom, Grim Fandango claimed first place on Chart-Track's weekly sales chart in December, before falling to ninth place.[122] It secured 12th after four weeks,[123] and 24th at the 13-week mark.[124] The game sold 58,617 copies and earned $2.33 million in the United States by the end of 1998,[125] and rose to 95,000 sales there by March 2000, according to PC Data.[126][127] Grim Fandango sold another 16,157 units in the region during 2001,[128] and 8,032 in the first six months of 2002;[129] its jewel case SKU reached 5,621 sales during 2003.[130] According to Tim Schafer, the game achieved sales of approximately 500,000 units by 2012,[131] around 50% fewer than Full Throttle had achieved.[132] It is commonly considered a commercial failure,[133][134][135] even though LucasArts stated that "Grim Fandango met domestic expectations and exceeded them worldwide".[136][137][34] The game had become profitable by 2000,[138] although Dave Grossman has said, "It was pretty ambitious and expensive, and I don't think it made very much money back."[131] A writer for Edge summarized in 2009, "While its reputation as a flop isn't entirely accurate, Grim's sales were either an indication that people preferred motorbikes to Gitanes-smoking corpses, or a sign of the times: adventure games were simply on their way out."[132]

While LucasArts proceeded to produce Escape from Monkey Island in 2000, they canceled development of sequels to Sam & Max Hit the Road[139] and Full Throttle[140] stating that "After careful evaluation of current market place realities and underlying economic considerations, we've decided that this was not the appropriate time to launch a graphic adventure on the PC."[139] Subsequently, the studio dismissed many of the people involved with their adventure games,[141][142] some of whom went on to set up Telltale Games, creating an episodic series of Sam & Max games.[143] These events, along with other changes in the video game market towards action-based games, are seen as primary causes in the decline of the adventure game genre.[24][144] Grim Fandango's underperformance was seen as a sign that the genre was commercially "dead" to rival Sierra, as well.[145] LucasArts stated in 2006 that they do not plan on returning to adventure games until the "next decade".[146] Ultimately the studio stopped developing video games in 2013 after The Walt Disney Company acquisition of Lucasfilm, and was dissolved shortly thereafter.

Tim Schafer left LucasArts shortly after Grim Fandango's release, and created his own company, Double Fine Productions, in 2000 along with many of those involved in the development of Grim Fandango. The company has found similar critical success with their first title, Psychonauts. Schafer stated that while there is strong interest from fans and that he "would love to go back and spend time with the characters from any game [he's] worked on", a sequel to Grim Fandango or his other previous games is unlikely as "I always want to make something new."[147] With the help of developers such as Double Fine and Telltale Games, adventure games saw a resurgence in the 2010s, with financially successful titles such as Broken Age, The Walking Dead, and The Wolf Among Us.

Remastered version

[edit]| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | PC: 84/100[148] PS4: 80/100[149] VITA: 84/100[150] iOS: 78/100[151] NS: 84/100[152] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Digital Trends | |

| Eurogamer | 8/10[153] |

| GameRevolution | |

| GameSpot | 8/10[155] |

| Hardcore Gamer | 4.5/5[165] |

| IGN | 9.3/10[156] |

| Nintendo Life | 9/10[162] |

| PC Gamer (US) | 80%[157] |

| PCGamesN | 7/10[163] |

| Push Square | 9/10[161] |

| Shacknews | 7/10[160] |

| TouchArcade | iOS: |

| USgamer |

Grim Fandango Remastered has received similar positive reception as the original release, with many critics continuing to praise the game's story, characters, and soundtrack. They also found the developer's commentary to be very insightful to the history of the game. Reviewers were disappointed at the lack of an auto-save system, as well as the game not receiving a full high-definition upgrade, leaving the higher-resolution characters somewhat out of place with the original 3D backgrounds.[153][155][156][157] Many reviewers also noted that the puzzles, though a staple of the day when Grim Fandango was first released, remain somewhat obtuse with solutions that are not clear even after the player solves them, and that a hint system, as was added to the Monkey Island remake, would have been very helpful.[153][157][166][167] The game's pacing, also unchanged from the original version, was also found harder to grasp, in both the pacing within the game's four acts, and the time taken to move around and between rooms.[168] In his review for Eurogamer, Richard Cobbett warned players to "be careful of rose-tinted memories", that while the remastered version is faithful to the original, it does show aspects of the original game that have become outdated in video game development.[153] Wired's Laura Hudson considered the remastered version highlighted how the original game was "an artifact of its time, an exceptional piece of interactive art wrapped inextricably around the technology and conventions of its time in a way that reveals both their limitations and the brilliance they were capable of producing".[169]

Legacy

[edit]In 2005, The Guardian characterized the game as "the last genuine classic to come from LucasArts, the company that helped define adventure games, Tim Schafer's noir-pastiche follows skull-faced Manny Calavera through a bureaucratic parody of the Land of the Dead. With a look that takes from both Mexican mythology and art deco, Grim Fandango is as unique an artistic statement as mainstream gaming has managed to offer. While loved by devotees, its limited sales prompted LucasArts to back away from original adventures to simply exploit franchises".[170]

Eurogamer's Jeffrey Matulef, in a 2012 retrospective look, believed that Grim Fandango's combination of film noir and the adventure game genre was the first of its kind and a natural fit due to the script-heavy nature of both, and would later help influence games with similar themes like the Ace Attorney series and L.A. Noire.[3]

Grim Fandango has been considered a representative title demonstrating video games as an art form; the game was selected in 2012 as a candidate for public voting for inclusion within the Smithsonian Institution's "The Art of Video Games" exhibit,[171] while the Museum of Modern Art seeks to install the game as an exhibit as part of its permanent collection within the Department of Architecture and Design.[172]

The game was included in the "Game Masters" exhibition, organized in 2012 by the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI); an event devoted to explore the faces and the history behind computer games. Tim Schafer was featured as the creative force behind Grim Fandango, within the exhibition section called "Game Changers", crediting him along a few other visionary game designers for having "pushed the boundaries of game design and storytelling, introducing new genres, creating our best-loved characters and revolutionising the way we understand and play games".[20]

Grim Fandango has been the centerpiece of a large fan community for the game that has continued to be active more than 10 years after the game's release.[173] Such fan communities include the Grim Fandango Network and the Department of Death, both of which include fan art and fiction in addition to other original content.[174]

In an interview with Kotaku after the announcement of the remaster, Schafer stated that he has long considered the idea of a Grim Fandango sequel to further expand on the setting of the game. He felt the story would be a difficult component, as either they would have to figure a means to bring Manny back from his final reward, or otherwise build the story around a new character. One option he has considered to alleviate the issue is by creating an adventure game using an open-world mechanic similar to the Grand Theft Auto series.[175]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Remastered version developed by Double Fine Productions.

- ^ Remastered version published by Double Fine Productions; Xbox One remastered version published by Xbox Game Studios.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "LucasArts' Grim Fandango Presents a Surreal Tale of Crime, Corruption and Greed in the Land of the Dead; Dramatic New Graphic Adventure from the Creator of Award-Winning Full Throttle Expected to Release in First Half 1998". Business Wire. September 8, 1997. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Evenson, Laura (October 27, 1998). "Fleshing Out an Idea". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ^ a b Matulef, Jeffery (February 5, 2012). "Retrospective: Grim Fandango". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Grim Fandango Instruction Manual (PDF). LucasArts. 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "The Greatest Games of All Time: Day of the Tentacle". GameSpot. April 30, 2004. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ^ LucasArts. Grim Fandango.

Celso: The Number Nine?

Manny: That's our top of the line express train. It shoots straight to the Ninth Underworld, the land of eternal rest in four minutes instead of four years. - ^ a b c Schafer, Tim (1997). "Grim Fandango Design Diaries". GameSpot. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Buxton, Chris (May 1998). "The Everlasting Adventure". PC Gamer. pp. 48–52.

- ^ Shaker, Wyatt (1999). "Grim Fandango Game Guide". GameSpot. Archived from the original on May 8, 1999. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ^ LucasArts. Grim Fandango.

Manny: Oh I can't leave here till I've worked off a little debt to the powers that be.

- ^ LucasArts. Grim Fandango.

Manny: Meche. I can see it in your face. And in your file here, where it says you're entitled to a first-class ticket to ... ...nowhere? WHAT?!

Meche: Did I do something wrong?

Manny: Not according to your bio! It was spotless! ... at least the part I read was. - ^ LucasArts. Grim Fandango.

Salvador: I was once a reaper like yourself Manuel, but I uncovered a web of corruption in our beloved Department of Death. I have reason to believe that the Bureau of Acquisitions is cheating the very souls it was charted to serve. I think someone is robbing these poor naïve souls of their rightful destinies, leaving them no option but to march on a treacherous trail of tears, unprotected and alone, like babies, Manuel, like babies.

- ^ LucasArts. Grim Fandango.

Meche: You were headed for a trap, I was trying to warn you. Domino was using me like bait. I didn't want you to end up a prisoner here like me.

- ^ LucasArts. Grim Fandango.

Mechanics: We shoot you now like an arrow into the wind. May you pierce the heart of the wind itself, and drink the blood of flight. Speed is the food of the great Glottis. Speed bring you life. Come back to us some day.

- ^ LucasArts. Grim Fandango.

Salvador: Manuel Calavera, we meet again. I am glad to see you have found what you were looking for. It is fortunate that you should arrive just now, as we, too, are about to achieve great success. Our army has grown, and right now our top agents are in Hector's weapons lab, about to close in on the enemy in his own den. I couldn't have done it without you, Manuel.

- ^ LucasArts. Grim Fandango.

Manny: Is this where you tell me all about your secret plan, Hector? How you stole Double N tickets from innocent souls, pretended to sell them but really hoarded them all for yourself in a desperate attempt to get out of the Land of the Dead?

- ^ LucasArts. Grim Fandango.

Meche: You can count them if you want. They're all here.

Gate Keeper: What about yours?

Manny: The company gave me one on the other end; sort of a retirement present. - ^ Ashburn, Jo (October 28, 1998). Grim Fandango: Prima's Official Strategy Guide. Roseville, California: Prima Games, Random House. ISBN 978-0761517979.

- ^ Cifaldi, Frank (February 3, 2012). "Happy Action, Happy Developer: Tim Schafer on Reimagining Double Fine". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2012.

- ^ a b "Let the Games Begin". Sunday Herald Sun. Australia. June 24, 2012. p. 12 – "Play" section.

- ^ a b "Inside the Mind – Designer Diaries – Page 1". Grim Fandango Network. Archived from the original on July 20, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2012.

- ^ Knibbe, Willem (April 10, 1998). "Preview: Grim Fandango". PC Games. Archived from the original on October 8, 1999. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ^ Smith, Rob (November 26, 2008). Rogue Leaders: The Story of LucasArts. Chronicle Books. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-8118-6184-7.

- ^ a b Cook, Daniel (May 7, 2007). "The Circle of Life: An Analysis of the Game Product Lifecycle". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2008.

- ^ Costikyan, Greg (October 21, 1998). "The adventure continues". Salon. Archived from the original on August 16, 2000. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Grim Fandango". Next Generation. No. 36. Imagine Media. December 1997. pp. 100–103.

- ^ Dutton, Fred (February 10, 2012). "Double Fine Adventure passes Day of the Tentacle budget". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on March 14, 2013. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- ^ Mogilefsky, Bret. "Lua in Grim Fandango". Grim Fandango Network. Archived from the original on February 18, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- ^ Blossom, Jon; Michaud, Collette (August 13, 1999). "Postmortem: LucasLearning's Star Wars DroidWorks". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on April 5, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ Ierusalimschy, Roberto; de Figueiredo, Luiz Henrique; Celes, Waldemar (2001). The Evolution of an Extension Language: A History of Lua. Proceedings of V Brazilian Symposium on Programming Languages. pp. B–14–B–28. Archived from the original on January 3, 2014. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ Waggoner, Ben; York, Halstead (January 3, 2000). "Video in Games: The State of the Industry". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on March 26, 2008. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Pearce, Celia (March 7, 2003). "Game Noir – A Conversation with Tim Schafer". International Journal of Computer Game Research. Archived from the original on September 14, 2013. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- ^ Rivera, Joshua (January 26, 2015). "'Grim Fandango' creator Tim Schafer talks his magnum opus -- a classic game lost for 16 years". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Grosso, Robert (February 5, 2015). "Gaming Obscura: Grim Fandango". TechRaptor. Archived from the original on April 21, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ a b c Siddiky, Asif (June 10, 2014). "A Closer Look at Grim Fandango's Surprise Revival". PlayStation Blog. Archived from the original on August 13, 2014. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ^ a b Purchase, Rob (November 6, 2008). "Grim Fandango design doc now on net". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ^ Purchese, Robert (November 6, 2008). "Grim Fandango design doc now on net". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Grim Fandango: Tim Schafer exhume un trésor" [Grim Fandango: Tim Schafer exhumes a treasure] (in French). France: Canard PC. November 6, 2008. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ McWhertor, Michael (November 5, 2008). "Tim Schafer Publishes Original Grim Fandango Design Doc". Kotaku. Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Matulef, Jeffrey (January 26, 2015). "Bringing out the Dead: Tim Schafer reflects back on Grim Fandango". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2015.

- ^ Mullen, Micheal (October 28, 1998). "Grim Fandango Releases". GameSpot. Archived from the original on February 26, 2000.

- ^ Nunnely, Stephany (June 9, 2014). "Grim Fandango remastered coming to PlayStation". VG247. Archived from the original on June 14, 2014. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- ^ Gera, Emily (June 9, 2014). "Grim Fandango is coming to PS4 and PS Vita (update)". Polygon. Archived from the original on June 13, 2014. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ^ "Grim Fandango platforms". Double Fine Productions. July 9, 2014. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ "Double Fine is Pleased to Announce..." Double Fine Productions. July 9, 2014. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ "Playstation Store: Grim Fandango Remastered". Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ "Playstation Trophies: Cross-Save Solution". February 2, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ Matuleft, Jeffrey (May 5, 2015). "Grim Fandango Remastered is out today on iOS and Android". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on May 7, 2015. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ^ Sarkar, Samit (December 30, 2015). "PlayStation Plus brings you Grim Fandango Remastered and more in January 2016". Polygon. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ Osborn, Alex (December 30, 2015). "Grim Fandango Remastered Headlines PlayStation Plus' Free Games for January". IGN. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tach, Dave (January 27, 2015). "Digital Archeology: How Double Fine, Disney, Lucasarts and Sony Resurrected Grim Fandango". Polygon. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c Grayson, Nathan (November 5, 2014). "The Crazy Journey To Save Grim Fandango". Kotaku. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ Diver, Mike (January 27, 2015). "Tim Schafer Discusses the Classic Video Games 'Grim Fandango' and 'Monkey Island'". VICE. Archived from the original on January 30, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ^ Ramsay, Randolph (June 9, 2014). "E3 2014: Remastered Grim Fandango heading to PS4, Vita - Tim Schafer's classic adventure game headed to current-gen Sony consoles". GameSpot. Archived from the original on October 2, 2014. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

- ^ Molina, Brett (June 11, 2014). "5 things from E3 Sony PS event". USA Today. p. 5B – Money Section.

- ^ a b McWhertor, Michael (October 10, 2014). "Grim Fandango returns with updated graphics, orchestral score and fan-made controls". Polygon. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- ^ Green, Jake (June 13, 2018). "Double Fine's Grim Fandango and Broken Age Head to Nintendo Switch". USGamer. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ Carter, Chris (November 1, 2018). "Surprise! Grim Fandango Remastered launches today on Switch". Destructoid. Archived from the original on September 12, 2022. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ Makedonski, Brett (May 13, 2020). "Grim Fandango, Full Throttle, and Day of the Tentacle finally break PS4 console exclusivity this year". Destructoid. Archived from the original on August 6, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Ward, Trent C. (November 3, 1998). "LucasArts flexes their storytelling muscle in this near-perfect adventure game". IGN. Archived from the original on September 12, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- ^ a b c Stabler, Brad; Twells, John; Bowe, Miles; Wilson, Scott; Lea, Tom (April 28, 2015). "The 100 best video game soundtracks of all time". Fact. United Kingdom. Archived from the original on April 30, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ a b "Grim Fandango Files". LucasArts. Archived from the original on February 14, 2007. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

- ^ Lubienski, Stefan (September 1, 2008). "Grim Fandango". Adventure Classic Gaming. Archived from the original on May 31, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2013.

- ^ "Grim Fandango Soundtrack". Amazon. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ "Grim Fandango – LucasArts flexes their storytelling muscle in this near-perfect adventure game". IGN Entertainment, Inc. November 3, 1998. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ "Grim Fandango Original Game Soundtrack :: Review by Chris". Square Enix Music Online. Archived from the original on December 26, 2010. Retrieved April 1, 2013.

- ^ Chandran, Neal. "Grim Fandango OGS". Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ a b Manny (1998). "Dang! I Left My Heart In The Land Of The Living!". Game Revolution. Archived from the original on August 20, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- ^ a b Warr, Philippa; Senior, Tom; Kelly, Andy (August 29, 2014). "The PC Gamer Top 100 - 21. Grim Fandango". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ "2nd Annual Interactive Achievement Awards". Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. 1999. Archived from the original on October 9, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Best and Worst of 1998: Special Achievement Awards". GameSpot. 1999. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ a b c "The Ten Best Game Soundtracks". GameSpot. 2000. Archived from the original on December 6, 2000. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ a b "Peter McConnell's classic Grim Fandango soundtrack reissued by Nile Rodgers' Sumthing Else". Fact. United Kingdom. May 5, 2015. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ Meer, Alec (April 24, 2015). "Play It Again, Manny: Grim Fandango Remastered OST". Rock Paper Shotgun. Archived from the original on March 26, 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ Thomas, Sean (November 1, 2018). "'Grim Fandango Remastered' Celebrates Nintendo Switch Launch with Vinyl". Archived from the original on November 2, 2018. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Grim Fandango (pc: 1998)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on July 3, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2008.

- ^ a b c Fournier, Heidi (May 20, 2002). "Grim Fandango Review". Adventure Gamers. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2008.

- ^ House, Michael L. "Grim Fandango". AllGame. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ Edge staff (October 28, 1998). "Grim Fandango Review". Edge. No. 65. Archived from the original on September 4, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Dulin, Ron (October 30, 1998). "Grim Fandango for PC Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on March 17, 2014. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ a b "Finals". Next Generation. No. 50. Imagine Media. February 1999. p. 96.

- ^ a b Hill, Steve (August 13, 2001). "Grim Fandango". PC Zone. Future plc. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved January 25, 2006.

- ^ "Grim Fandango". Adventure Gamers. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ Silverman, Dwight (December 15, 1998). "Outstanding in their fields". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 10, 2004. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ^ Fulljames, Stephan (August 15, 2001). "PC Review: Grim Fandango". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on March 14, 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ "Top 50 Games of All Time". Next Generation. No. 50. Imagine Media. February 1999. p. 77.

- ^ a b "PC Gamer Fifth Annual Awards". Vol. 6, No. 3. PC Gamer. March 1999.

- ^ a b "A Selection of Awards and Accolades for Recent LucasArts Releases". LucasArts. Archived from the original on May 7, 2008. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ^ a b IGN Staff (January 31, 1999). "IGNPC's Best of 1998 Awards". IGN. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- ^ a b "GameSpot's Best of E3: Grim Fandango". GameSpot. 1998. Archived from the original on December 9, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ a b "Best and Worst of 1998: Genre Awards". GameSpot. 1999. Archived from the original on February 24, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ a b "Best and Worst of 1998: Game of the Year". GameSpot. 1999. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ a b "Best and Worst of 1998: Special Achievement Awards". GameSpot. 1999. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ a b Leone, Matt (March 30, 2009). "Tim Schafer Profile". 1UP. Retrieved April 1, 2009.

- ^ a b "The Ten Best Readers Endings". GameSpot. 2000. Archived from the original on December 2, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ a b "Second Interactive Achievement Awards - Computer". Interactive.org. Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on November 4, 1999. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Clarke, Stuart (May 29, 1999). "INSERT; Games". Sydney Morning Herald. Australia. p. 13 – Computers section.

- ^ a b "Second Interactive Achievement Awards - Game of the Year". Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on November 4, 1999. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Second Interactive Achievement Awards - Craft Award". Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on November 3, 1999. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Greatest Games of All Time – Grim Fandango". GameSpot. 2003. Archived from the original on December 6, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ a b Leeper, Justin (April 10, 2004). "Hall of Fame: Grim Fandango". GameSpy. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ a b "25 Most Underrated Games of All Time – Grim Fandango". GameSpy. 2003. Archived from the original on January 2, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ a b Dickens, Evan (April 2, 2004). "Top 20 Adventure Games of All-Time". Adventure Gamers. Archived from the original on August 13, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- ^ a b "Top 100 All-Time Adventures". Adventure Gamers. December 30, 2011. Archived from the original on May 13, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2015.

- ^ Adams, Dan; Butts, Steve; Onyett, Charles (March 16, 2007). "Top 25 PC Games of All Time". IGN. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- ^ a b "Top 100 Games of All Time". IGN. 2007. Archived from the original on November 29, 2007. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- ^ a b Jason, Ocampo; Butts, Steve; Haynes, Jeff (September 27, 2010). "Top 25 PC Games – 2009 Edition". IGN. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ "Gamecenter takes a look at 1998 and chooses the best games of the year!". CNET Gamecenter. United States. January 29, 1999. Archived from the original on December 17, 2000.

- ^ CGW staff (April 1999). "The Best of the Year". Computer Gaming World. No. 177. Ziff Davis. p. 96.

- ^ "Los Mejores Juegos del 98" [The Best Games of 1998]. Micromanía (in Spanish). 3 [Tercera Época] (47). Spain: Hobby Press: 44, 48. December 1998.

- ^ "1998 Winners". Game Critics Awards. 1998. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ^ "Personal Computer Awards". Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on November 4, 1999. Retrieved June 29, 2023.

- ^ "Top 10 adventure games of the 20th century". Adventure Classic Gaming. January 1, 2000. Archived from the original on March 10, 2006. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- ^ CGW staff (February 2001). "Welcome to the Cooperstown of Computer Games - Hall of Fame - Inductions: Grim Fandango, Half-Life". Computer Gaming World. No. 199. Ziff Davis. pp. 62–63.

- ^ Adams, Dan; Butts, Steve; Onyett, Charles (March 16, 2007). "Top 25 PC Games of All Time". IGN. p. 2 (web). Archived from the original on March 25, 2007.

(...)there was a time when LucasArts was known as the industry's best adventure game developer. With a roster of superlative titles, the company had already cemented its reputation in the annals of gaming. Then they went one step further with a game that many consider the greatest adventure game of all time.

- ^ PC Gamer staff (February 15, 2011). "The 100 best PC games of all time". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ Peckham, Matt (November 15, 2012). "All-Time 100 Video Games - From Adventure to Zork, here are our picks for the All-Time 100 greatest video games". Time. New York, U.S. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ^ Kohler, Chris; Groen, Andrew; Rigney, Ryan (May 6, 2013). "The Most Jaw-Dropping Game Graphics of the Last 20 Years - 1998: Grim Fandango =". Wired. Archived from the original on April 8, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Video Games of All Time - 84. Grim Fandango". Empire. United Kingdom. 2014. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ^ Albertson, Joshua (December 8, 1998). "Tech Gifts of the Season". Smart Money. Archived from the original on December 21, 2004. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ^ Feldman, Curt (November 25, 1998). "Top Sellers of the Week". GameSpot. Archived from the original on June 9, 2000.

- ^ Mallinson, Paul (January 1999). "Charts; The ChartTrack Top 10". PC Zone (72): 22.

- ^ "PC Gaming World's ELSPA Chart". GameSpot UK. December 4, 1998. Archived from the original on December 6, 1998. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ "PC Gaming World's ELSPA Charts". GameSpot UK. January 27, 1999. Archived from the original on January 28, 1999. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ Staff (April 1999). "The Numbers Game; Does Award Winner = Best Seller?". PC Gamer US. 6 (4): 50.

- ^ Sluganski, Randy (March 2000). "(Not) Playing the Game; Part 4". Just Adventure. Archived from the original on April 20, 2001.

- ^ Sluganski, Randy (July 2000). "The State of Adventure Gaming". Just Adventure. Archived from the original on April 20, 2001.

- ^ Sluganski, Randy (March 2002). "State of Adventure Gaming - March 2002 - 2001 Sales Table". Just Adventure. Archived from the original on June 19, 2002.

- ^ Sluganski, Randy (August 2002). "State of Adventure Gaming - August 2002 - June 2002 Sales Table". Just Adventure. Archived from the original on March 14, 2005.

- ^ Sluganski, Randy (March 2004). "Sales December 2003 - The State of Adventure Gaming". Just Adventure. Archived from the original on April 11, 2004.

- ^ a b Winegarner, Beth (May 23, 2012). "The Adventures of a Videogame Rebel: Tim Schafer at Double Fine". SF Weekly. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017.

- ^ a b Staff (August 2009). "Master of Unreality". Edge. No. 204. United Kingdom: Future Publishing. pp. 82–87.

- ^ Brenasal, Barry (January 4, 2000). "Y2K the game, appropriately enough, is a dud". CNN. Archived from the original on September 24, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ Barton, Matt (November 5, 2005). "Review: LucasArts' Grim Fandango (1998)". Gameology. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- ^ Fahs, Travis (March 3, 2008). "The Lives and Deaths of the Interactive Movie". IGN. Archived from the original on March 6, 2008. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- ^ Christof, Bob (June 26, 2000). "Lucasarts ziet het licht" (in Dutch). Gamer.nl. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- ^ "The Future Of LucasArts". Daily Radar. May 25, 2000. Archived from the original on June 27, 2001. Retrieved March 19, 2008. "Although LucasArts, a privately held company, will not release sales figures, a spokesperson expressed confidence in the history and future of LucasArt's [sic] original titles. 'The response to the Monkey Island series has been phenomenal,' he said. '[And] Grim Fandango met domestic expectations and exceeded them worldwide.'"

- ^ Ajami, Amer (September 8, 2000). "Escape from Monkey Island Preview". GameSpot. Archived from the original on November 17, 2000.

- ^ a b Thorsen, Tor (March 4, 2003). "Sam & Max sequel canceled". GameSpot. Archived from the original on March 23, 2014. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ Parker, Sam (August 7, 2003). "LucasArts cancels Full Throttle". GameSpot. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ "A Short History of LucasArts". Edge. Future plc. August 26, 2006. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved February 2, 2009.

- ^ Feldman, Curt (August 13, 2004). "LucasArts undergoing "major restructuring"". GameSpot. Archived from the original on October 4, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2009.

- ^ Jenkins, David (October 4, 2004). "Sam & Max 2 Developers Form New Studio". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on December 30, 2013. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ Lindsay, Greg (October 8, 1998). "Myst And Riven Are A Dead End. The Future Of Computer Gaming Lies In Online, Multiplayer Worlds". Salon. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ^ "Adventure Series: Part III Feature". The Next Level. November 28, 2005. Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ "LucasArts at E3". G4tv. 2006. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2008.

- ^ "Geniuses at Play". Playboy. 2007. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ "Grim Fandango Remastered for PC Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ "Grim Fandango Remastered for PlayStation 4 Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ "Grim Fandango Remastered for PlayStation Vita Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ "Grim Fandango Remastered for iPhone/iPad Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ "Grim Fandango Remastered for Switch Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Cobbett, Richard (January 27, 2015). "Grim Fandango Remastered review". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ Nick_Tan (2015). "Grim Fandango Remastered Review". Game Revolution. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ^ a b VanOrd, Kevin (January 27, 2015). "Grim Fandango Remastered Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ a b McCaffrey, Ryan (January 26, 2015). "Rise from Your Grave". IGN. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c Senior, Tom (January 27, 2015). "grim fandango remastered". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on January 30, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ Fretz, Andrew (May 27, 2015). "'Grim Fandango Remastered' Review – Dust off the Bones Before you Roll Em". TouchArcade. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ Mackey, Bob (February 4, 2015). "Grim Fandango Remastered PS4 Review: A Bone to Pick". USgamer. Archived from the original on November 27, 2022. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ^ Perez, Daniel (January 27, 2015). "Grim Fandango Remastered Review: Los Muertos Resucitan". Shacknews. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ^ Banas, Graham (January 29, 2015). "Review: Grim Fandango Remastered (PlayStation 4)". Push Square. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ^ Reseigh-Lincoln, Dom (November 16, 2018). "Review: Grim Fandango Remastered - Still One Of The Greatest Point-And-Click Adventures Ever Made". Nintendo Life. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ^ Brown, Fraser (January 27, 2015). "Grim Fandango Remastered PC review". PCGamesN. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ^ Agnello, Anthony (January 29, 2015). "Grim Fandango tells a lively, relatable story set in the land of the dead". Digital Trends. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ^ Thew, Geoff (January 27, 2015). "Review: Grim Fandango Remastered - Hardcore Gamer". Hardcore Gamer. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ^ Cragg, Oliver (February 4, 2015). "Grim Fandango Remastered review: it's worth admiring this lovingly restored antique". The Independent. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ Byrd, Christopher (February 3, 2015). "Grim Fandango Remastered review: A witty but tedious classic". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ Strom, Steven (January 27, 2015). "Grim Fandango Remastered is a flawed remake of a considered masterpiece". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ Hudson, Laura (January 29, 2015). "I Love You, Grim Fandango, Even Though You're Broken". Wired. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- ^ Gillen, Kieron (September 15, 2005). "Technology: Back story: The titles that defined Fahrenheit's genre". The Guardian. London. p. 3 – Technology Pages.

- ^ "The Art of Video Games Exhibition Checklist" (PDF). Smithsonian Institution. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 19, 2013. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ Savage, Phil (November 30, 2012). "Museum of Modern Art to install 14 games, including EVE, Dwarf Fortress and Portal". PC Magazine. Archived from the original on October 4, 2014. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ Alderman, Naomi (January 21, 2010). "G2: Games:The Player". The Guardian. London. p. 17, Feature Pages.

- ^ Barlow, Nova (March 4, 2008). "Walk, Don't Run". The Escapist. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- ^ Grayson, Nathan (November 4, 2014). "Tim Schafer Dreams Of An Open-World Grim Fandango Sequel". Kotaku. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

Sources

[edit]- Schafer, Tim; Tsacle, Peter; Ingerson, Eric; Mogilefsky, Bret; Chan, Peter (1996). "Grim Fandango Puzzle Document". LucasArts. Archived from the original on December 12, 2008. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Robertson, Adi (November 3, 2018). "Remembering Grim Fandango: this week in tech, 20 years ago". The Verge. Archived from the original on November 4, 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- The Making of Grim Fandango Remastered by 2 Player Productions: Episode 1, Episode 2, Episode 3

- Ashburn, Jo (October 28, 1998). Grim Fandango: Prima's Official Strategy Guide Paperback. Prima Games. ISBN 978-0761517979.

- McConnell, Peter (September 1999). "Dance of the Dead: The Adventures of a Composer Creating the Game Music for Grim Fandango". Electronic Musician. 15 (9). New York: NewBay Media, LLC: 30–32, 35–36, 38–40, 42. ISSN 0884-4720.

- Schafer, Tim; Tsacle, Peter; Ingerson, Eric; Mogilefsky, Bret; Chan, Peter (1996). "Grim Fandango Puzzle Document". LucasArts. Archived from the original on December 12, 2008. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- 1998 video games

- Android (operating system) games

- Day of the Dead

- IOS games

- Linux games

- Lua (programming language)-scripted video games

- LucasArts games

- Magic realism

- MacOS games

- Neo-noir video games

- Nintendo Switch games

- PlayStation 4 games

- PlayStation Network games

- PlayStation Vita games

- Point-and-click adventure games

- Retrofuturistic video games

- ScummVM-supported games

- Single-player video games

- Video games about personifications of death

- Video games about skeletons

- Video games developed in the United States

- Video games scored by Peter McConnell

- Video games with pre-rendered 3D graphics

- Video games about the afterlife

- Video games set in the 1950s

- Windows games

- Xbox One games