Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna of Russia

| Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna of Russia | |

|---|---|

Olga Alexandrovna c. 1910 | |

| Born | 13 June 1882 [O.S. June 1] Peterhof Palace, Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Died | 24 November 1960 (aged 78) Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | |

| Issue |

|

| House | Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov |

| Father | Alexander III of Russia |

| Mother | Dagmar of Denmark |

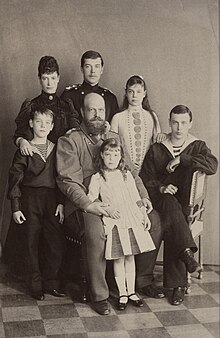

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna of Russia (Russian: Ольга Александровна; 13 June [O.S. 1 June] 1882 – 24 November 1960) was the youngest child of Emperor Alexander III of Russia and younger sister of Emperor Nicholas II.

Olga was raised at the Gatchina Palace outside Saint Petersburg. Olga's relationship with her mother, Empress Marie, the daughter of King Christian IX of Denmark, was strained and distant from childhood. In contrast, she and her father were close. He died when she was 12, and her brother Nicholas became emperor. In 1901, at 19, she married Duke Peter Alexandrovich of Oldenburg, who was privately believed by family and friends to be homosexual. Their marriage of 15 years remained unconsummated, and Peter at first refused Olga's request for a divorce. The couple led separate lives and their marriage was eventually annulled by the Emperor in October 1916. The following month Olga married cavalry officer Nikolai Kulikovsky, with whom she had fallen in love several years before. During the First World War, Olga served as an army nurse and was awarded a medal for personal gallantry. At the downfall of the Romanovs in the Russian Revolution of 1917, she fled with her husband and children to Crimea, where they lived under the threat of assassination. Her brother Nicholas and his family were shot and bayoneted to death by revolutionaries.

Olga escaped revolutionary Russia with her second husband and their two sons in February 1920. They joined her mother, the Dowager Empress, in Denmark. In exile, Olga acted as companion and secretary to her mother and was often sought out by Romanov impostors who claimed to be her dead relatives. She met Anna Anderson, the best-known impostor, in Berlin in 1925. After the Dowager Empress's death in 1928, Olga and her husband purchased a dairy farm in Ballerup, near Copenhagen. She led a simple life: raising her two sons, working on the farm and painting. During her lifetime, she painted over 2,000 works of art, which provided extra income for both her family and the charitable causes she supported.

In 1948, feeling threatened by Joseph Stalin's regime, Olga and her immediate family relocated to a farm in Campbellville, Ontario, Canada. With advancing age, Olga and her husband moved to a bungalow near Cooksville, Ontario. Colonel Kulikovsky died there in 1958. Two years later, as her health deteriorated, Olga moved with friends to a small apartment in East Toronto. She died aged 78, seven months after her older sister, Xenia. At the end of her life and afterwards, Olga was widely labelled the last Grand Duchess of Imperial Russia.

Early life

[edit]

Olga was the youngest daughter of Emperor Alexander III and his consort, Empress Marie, formerly Princess Dagmar of Denmark. She was born in the purple (i.e., during her father's reign) on 13 June 1882 in the Peterhof Palace, west of central Saint Petersburg. Her birth was announced by a traditional 101-gun salute from the ramparts of the Peter and Paul Fortress, and similar salutes throughout the Russian Empire.[1] Her mother, advised by her sister, Alexandra, Princess of Wales, placed Olga in the care of an English nanny, Elizabeth Franklin.[1]

The Russian imperial family was a frequent target for assassins, so for safety reasons the Grand Duchess was raised at the country palace of Gatchina, about 50 miles (80 km) west of Saint Petersburg. Although Olga and her siblings lived in a palace, conditions in the nursery were modest, even Spartan.[2] They slept on hard camp beds, rose at dawn, washed in cold water, and ate a simple porridge for breakfast.[2]

Olga left Gatchina for the first time in 1888 when the imperial family visited the Caucasus. On 29 October, their return train approached the small town of Borki at speed. Olga's parents and their four older children were eating lunch in the dining-car when the train lurched violently and came off the rails. The carriage was torn open; the heavy iron roof caved in, and the wheels and floor of the car were sliced off. Survivors claimed the Tsar crawled out from beneath the crushed roof, and held it up with "a Herculean effort" so that the others could escape;[3] a story subsequently considered unbelievable.[4] There were 21 fatalities. Empress Marie helped tend the wounded and made makeshift bandages from her own clothes.[5] An official investigation found that the crash was an accident,[6] but it was widely and falsely believed that two bombs had been planted on the line.[5]

The Grand Duchess and her siblings were taught at home by private tutors. Subjects included history, geography, Russian, English, and French, as well as drawing and dancing.[7] Physical activities such as equestrianism were taught at an early age, and the children became expert riders.[8]

The family was deeply religious. While Christmas and Easter were times of celebration and extravagance, Lent was strictly observed—meat, dairy products and any form of entertainment were avoided.[9]

Empress Marie was reserved and formal with Olga as a child, and their relationship remained a difficult one.[10] But Olga, her father, and the youngest of her brothers, Michael, had a close relationship. Together, the three frequently went on hikes in the Gatchina forests, where the Tsar taught Olga and Michael woodsmanship.[11] Olga said of her father:

My father was everything to me. Immersed in work as he was, he always spared that daily half-hour. ... once my father showed me a very old album full of most exciting pen and ink sketches of an imaginary city called Mopsopolis, inhabited by Mopses [pug dogs]. He showed it to me in secret, and I was thrilled to have him share his own childhood secrets with me.[12]

Family holidays were taken in the summer at Peterhof and with Olga's grandparents in Denmark.[13] However, in 1894, Olga's father became increasingly ill, and the annual trip to Denmark was cancelled.[14] On 13 November 1894, he died at the age of 49. The emotional impact on Olga, aged 12, was traumatic,[15] and her eldest brother, the new Tsar Nicholas II, was propelled into a role for which, in Olga's later opinion, he was ill-prepared.[16]

Court life

[edit]Olga was due to enter society in mid-1899 at the age of 17, but after the death of her brother George at the age of 28, her first official public appearance was delayed by a year until 1900.[17] She hated the experience, and later told her official biographer Ian Vorres, "I felt as though I were an animal in a cage—exhibited to the public for the first time."[18] From 1901 Olga served as the honorary Commander-in-Chief of the 12th Akhtyrsky Hussar Regiment of the Imperial Russian Army. The Akhtyrsky Hussars, famous for their victory over Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle of Kulm in 1813, wore a distinctive brown dolman.[19]

By 1900, Olga, aged 18, was being escorted to the theatre and opera by a distant cousin, Duke Peter Alexandrovich of Oldenburg, a member of the Russian branch of the House of Oldenburg.[20] He was 14 years her senior and known for his passion for literature and gambling.[21] Peter asked for Olga's hand in marriage the following year, a proposal that took the Grand Duchess completely by surprise: "I was so taken aback that all I could say was 'thank you'," she later explained.[22]

Their engagement, announced in May 1901, surprised family and friends, as Peter had shown no prior interest in women,[18] and members of society assumed he was homosexual.[23] At the age of 19, on 9 August [O.S. 27 July] 1901, Olga married 33-year-old Peter. After the celebration the newlyweds left for the Oldenburg palace on the Field of Mars. Olga spent her wedding night alone in tears, while her husband left for a gambling club, returning the next morning.[24] Their marriage remained unconsummated,[25] and Olga suspected that Peter's ambitious mother had pushed him into proposing.[26] Biographer Patricia Phenix thought Olga may have accepted his proposal to gain independence from her own mother, the Dowager Empress, or to avoid marriage into a foreign court.[27] The couple initially lived with her in-laws Alexander Petrovich and Eugénie Maximilianovna of Oldenburg. The arrangement was not harmonious, as Peter's parents, both well known for their philanthropic work, berated their only son for his laziness.[24] Olga took a dislike to her mother-in-law; although Eugénie, a close friend of the Dowager Empress, gave her daughter-in-law many gifts, including a ruby tiara that Napoleon had given as a present to Joséphine de Beauharnais.[24] A few weeks after the wedding Olga and her husband travelled to Biarritz, France, from where they sailed to Sorrento, Italy, on a yacht loaned to them by King Edward VII of Great Britain.[28]

On their return to Russia, they settled into a 200-room palace (the former Baryatinsky mansion) at 46 Sergievskaya Street (present-day Tchaikovsky Street) in Saint Petersburg.[29] (The palace, a gift from Tsar Nicholas II to his sister, now houses the Saint Petersburg Chamber of Commerce and Industry.) Olga and Peter had separate bedrooms at opposite ends of the building, and the Grand Duchess had her own art studio.[28] Unhappy in her marriage, she fell into bouts of depression that caused her to lose her hair, forcing her to wear a wig. It took two years for her hair to regrow.[24]

Near the Oldenburgs' estate, Ramon in Voronezh province, Olga had her own villa, called "Olgino" after the local town.[30] She subsidized the village school out of her own pocket, and established a hospital.[31] Her daughter-in-law later wrote, "She tried to help every needy person as far as her strengths and means would permit."[31] At the hospital she learned basic medical treatment and proper care from the local doctor.[32] She exemplified her strong Orthodox faith by creating religious icons, which she distributed to the charitable endeavours she supported.[31] At Ramon, Olga and Peter enjoyed walking through the nearby woods and hunted wolves together.[33] He was kind and considerate towards her, but she longed for love, a normal marriage, and children.[28]

In April 1903, during a royal military review at Pavlovsk Palace, Olga's brother Michael introduced her to a Blue Cuirassier Guards officer, Nikolai Kulikovsky.[34] Olga and Kulikovsky began to see each other and exchanged letters regularly. The same year, at the age of 22, she confronted her husband and asked for a divorce, which he refused – with the qualification that he might reconsider after seven years.[35] Nevertheless, Oldenburg appointed Kulikovsky as an aide-de-camp, and allowed him to live in the same residence as Oldenburg and the Grand Duchess on Sergievskaya Street.[36] The relationship between Kulikovsky and the Grand Duchess was not public,[37] but gossip about their romance spread through society.[38]

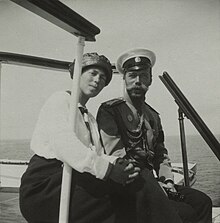

From 1904 to 1906 Duke Peter had an appointment to a military post in Tsarskoye Selo, a complex of palaces just south of Saint Petersburg. In Tsarskoye Selo, the Grand Duchess grew close to her brother Nicholas and his family, who lived at the Alexander Palace near her own residence.[39] Olga prized her connection to the Tsar's four daughters.[40] From 1906 to 1914, Olga took her nieces to parties and engagements in Saint Petersburg, without their parents, every weekend throughout the winter.[40] She especially took a liking to the youngest of Nicholas's daughters, her god-daughter Anastasia, whom she called Shvipsik ("little one").[41] Through her brother and sister-in-law, Olga met Rasputin, a self-styled holy man who purported to have healing powers. Although she made no public criticisms of Rasputin's association with the imperial family, she was unconvinced of his supposed powers and privately disliked him.[42] As Olga grew close to her brother's family, her relationship with her other surviving brother, Michael, deteriorated. To her and Nicholas's horror, Michael eloped with his mistress, a twice-divorced commoner, and communication between Michael and the rest of the family essentially ceased.[43]

Public unrest over the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905 and demands for political reform increased in the early years of the twentieth century. At Epiphany 1905, a band of revolutionaries fired live rounds at the Winter Palace from the Peter and Paul Fortress. Olga and the Dowager Empress were showered with glass splinters from a smashed window, but remained unharmed.[44] Three weeks later, on "Bloody Sunday" (22 January [O.S. 9 January] 1905), Cossack troops killed at least 92 people during a demonstration,[45] and a month later Olga's uncle, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich of Russia, was assassinated.[46] Uprisings occurred throughout the country, and parts of the navy mutinied.[47] Olga supported the appointment of the liberal Pyotr Stolypin as prime minister, and he embarked on a programme of gradual reform, but in 1911 he was assassinated.[48] The public unrest, Michael's elopement, and Olga's sham marriage placed her under strain, and in 1912, while visiting England with her mother, she suffered a nervous breakdown.[49] Tsarina Alexandra was also unwell with fatigue, concerned by the poor health of her hemophiliac son, Alexei.[50] Olga stood in for the Tsarina at public events and accompanied her brother on a tour of the interior, while the Tsarina remained at home.[51]

War and revolution

[edit]

On 1 August 1914, with World War I looming, Olga's regiment, the Akhtyrsky Hussars, appeared at an Imperial Review before her and the Tsar at Krasnoe Selo.[52] Kulikovsky volunteered for service with the Hussars, who were stationed on the frontlines in Southwestern Russia.[19] With the Grand Duchess's prior medical knowledge from the village of Olgino, she started work as a nurse at an under-staffed Red Cross hospital in Rovno, near to where her own regiment was stationed.[53] During the war, she came under heavy Austrian fire while attending the regiment at the front. Nurses rarely worked so close to the frontline and consequently, she was awarded the Order of St. George by General Mannerheim, who later became President of Finland.[19] As the Russians lost ground to the Central Powers, Olga's hospital was moved eastwards to Kiev,[54] and Michael returned to Russia from exile abroad.[55]

In 1916, Tsar Nicholas II annulled the marriage between Duke Peter Alexandrovich and the Grand Duchess, allowing her to marry Colonel Kulikovsky.[56] The service was performed on 16 November 1916 in the Kievo-Vasilievskaya Church on Triokhsviatitelskaya (Three Saints Street) in Kiev. The only guests were the Dowager Empress, Olga's brother-in-law Grand Duke Alexander, four officers of the Akhtyrsky Regiment, and two of Olga's fellow nurses from the hospital in Kiev.[57]

During the war, internal tensions and economic deprivation in Russia continued to mount and revolutionary sympathies grew. After Tsar Nicholas II abdicated in early 1917, many members of the Romanov dynasty, including Nicholas and his immediate family, were detained under house arrest. In search of safety, the Dowager Empress, Grand Duke Alexander, and Grand Duchess Olga travelled to Crimea by special train, where they were joined by Olga's sister (Alexander's wife) Grand Duchess Xenia.[58] They lived at Alexander's estate, Ai-Todor, about 12 miles (19 km) from Yalta, where they were placed under house arrest by the local forces.[59] On 12 August 1917, her first child and son, Tikhon Nikolaevich was born during their virtual imprisonment. He was named after Tikhon of Zadonsk, the Saint venerated near the Grand Duchess's estate at Olgino.[19]

The Romanovs isolated in Crimea knew little of the fate of the Tsar and his family. Nicholas, Alexandra, and their children were originally held at their official residence, the Alexander Palace, but the Provisional government under Alexander Kerensky relocated them to Tobolsk, Siberia. In February 1918, most of the imperial family at Ai-Todor was moved to another estate at Djulber, where Grand Dukes Nicholas and Peter were already under house arrest. Olga and her husband were left at Ai-Todor. The entire Romanov family in Crimea was condemned to death by the Yalta revolutionary council, but the executions were delayed by political rivalry between the Yalta and Sevastopol Soviets.[60] By March 1918, the Central Power of Germany had advanced on Crimea, and the revolutionary guards were replaced by German ones.[61] In November 1918, the German forces were informed that their nation had lost the war, and they evacuated homewards. Allied forces took over the Crimean ports, in support of the loyalist White Army, which allowed the surviving members of the Romanov family time to escape abroad. The Dowager Empress and, at her insistence, most of her family and friends were evacuated by the British warship HMS Marlborough. Nicholas II had already been shot dead and the family assumed, correctly, that his wife and children had also been killed.[62]

Olga and her husband refused to leave Russia and decided to move to the Caucasus, which the White Army had cleared of revolutionary Bolsheviks.[63] An imperial bodyguard, Timofei Yatchik, guided them to his hometown, the large Cossack village of Novominskaya. In a rented five-room farmhouse there, Olga gave birth to her second son, Guri Nikolaevich, on 23 April 1919.[64] He was named after a friend of hers, Guri Panayev, who was killed while serving in the Akhtyrsky Regiment during World War I. In November 1919, the family set out on what would be their last journey through Russia. Just ahead of revolutionary troops, they escaped to Novorossiysk and took refuge in the residence of the Danish consul, Thomas Schytte, who informed them of the Dowager Empress's safe arrival in Denmark.[65] After a brief stay with the consul, the family was shipped to a refugee camp on the island of Büyükada in the Dardanelles Strait near Istanbul, Turkey, where Olga, her husband and children shared three rooms with eleven other adults.[66] After two weeks, they were evacuated to Belgrade in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes where she was visited by Prince Regent Alexander. Alexander offered the Grand Duchess and her family a permanent home, but Olga was summoned to Denmark by her mother.[65] On Good Friday 1920, Olga and her family arrived in Copenhagen. They lived with the Dowager Empress, at first at the Amalienborg Palace and then at the royal estate of Hvidøre, where Olga acted as her mother's secretary and companion.[67] It was a difficult arrangement at times. The Dowager Empress insisted on having Olga at her beck and call and found Olga's young sons too boisterous. Having never reconciled with the idea of her daughter's marriage to a commoner, she was cold towards Kulikovsky, rarely allowing him in her presence. At formal functions, Olga was expected to accompany her mother alone.[68]

Anna Anderson

[edit]

In 1925, Olga and Colonel Kulikovsky travelled to Berlin to meet Anna Anderson, who claimed to be Olga's niece, Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia. Anderson had attempted suicide in Berlin in 1920, which Olga later called "probably the only indisputable fact in the whole story".[69] Anderson claimed that with the help of a man named Tchaikovsky she had escaped from revolutionary Russia via Bucharest, where she had given birth to his child. Olga thought the story "palpably false",[70] since Anderson made no attempt to approach Queen Marie of Romania (first cousin of both of Anastasia's parents), during her entire alleged time in Bucharest. Olga said:

If Mrs. Anderson had indeed been Anastasia, Queen Marie would have recognized her on the spot. ... Marie would never have been shocked at anything, and a niece of mine would have known it. ... There is not one tittle of genuine evidence in the story. The woman keeps away from the one relative who would have been the first to recognize her, understand her desperate plight, and sympathize with her.[70]

Anderson stated she was in Berlin to inform Princess Irene of Prussia (sister of Tsarina Alexandra and cousin of Tsar Nicholas II) of her survival. Olga commented, "[Princess Irene] was one of the most straightlaced women in her generation. My niece would have known that her condition would have indeed have shocked [her]."[70]

Olga met Anderson, who was being treated for tuberculosis, at a nursing home. Of the visit Olga later said:

My beloved Anastasia was fifteen when I saw her for the last time in the summer of 1916. She would have been twenty-four in 1925. I thought Mrs. Anderson looked much older than that. Of course, one had to make allowances for a very long illness ... All the same, my niece's features could not possibly have altered out of all recognition. The nose, the mouth, the eyes were all different.[71] ... As soon as I sat down by that bed in the Mommsen Nursing Home, I knew I was looking at a stranger. ... I had left Denmark with something of a hope in my heart. I left Berlin with all hope extinguished.[72]

Olga also said she was dismayed that Anderson spoke only German and showed no sign of knowing either English or Russian, while Anastasia spoke both those languages fluently and was ignorant of German.[73] Nevertheless, Olga remained sympathetic towards Anderson, perhaps because she thought that she was ill rather than deliberately deceitful.[74] Olga later explained:

... she did not strike me as an out-and-out impostor. Her brusqueness warred against it. A cunning impostor would have done all she could to ingratiate herself ... But Mrs. Anderson's manner would have put anyone off. My own conviction is that it all started with some unscrupulous people who hoped they might lay their hands on at least a share of the fabulous and utterly non-existent Romanov fortune ... I had a feeling she was 'briefed,' as it were, but far from perfectly. The mistakes she made could not all be attributed to lapses of memory. For instance, she had a scar on one of her fingers and she kept telling everybody that it had been crushed because of a footman shutting the door of a landau too quickly. And at once I remembered the real incident. It was Marie, her elder sister, who got her hand hurt rather badly, and it did not happen in a carriage but on board the imperial train. Obviously someone, having heard something of the incident, had passed a garbled version of it to Mrs. Anderson.[72]

Conceivably, Olga was initially either open to the possibility that Anderson was Anastasia or unable to make up her mind.[75] Anderson's biographer and supporter Peter Kurth claimed that Olga wrote to the Danish ambassador, Herluf Zahle, at the end of October 1925: "My feeling is that she is not the one she believes—but one can't say she is not as a fact".[76] Within a month she had made up her mind. She wrote to a friend, "There is no resemblance, and she is undoubtedly not A."[77][78] Olga sent Anderson a scarf and five letters, which were used by Anderson's supporters to claim that Olga recognized Anderson as Anastasia.[79] Olga later said she sent the gift and letters "out of pity",[80] and called the claims "a complete fabrication".[80] When Olga refused to recognize Anderson as Anastasia publicly and published a statement denying any resemblance in a Danish newspaper,[81] Anderson's supporters, Harriet von Rathlef and Gleb Botkin, claimed that Olga was acting on instructions received from her sister Xenia by telegram, which Olga denied in private letters and sworn testimony.[82][83] She told her official biographer, "I never received any such telegram."[80] The telegram was never produced by Anderson's supporters, and it has never been found among any of the papers relating to the case.[84] Xenia said,

[Anderson's supporters] told the most terrible lies about my sister and me ... I was supposed to have sent Olga a telegram saying, 'On no account recognize Anastasia.' That was a fantasy. I never sent any telegrams, or gave my sister any advice about her visit to Berlin. We were all apprehensive about the wisdom of her going, but only because we feared it would be used for propaganda purposes by the claimant's supporters. ... My sister Olga felt sorry for that poor woman. She was kind to her, and because of her kindness of heart, her opinions and motives have been misrepresented.[85]

Danish residency and exodus

[edit]

The Dowager Empress died on 13 October 1928 at Hvidøre. Her estate was sold and Olga purchased Knudsminde, a farm in Ballerup about 20 kilometres (12 mi) from central Copenhagen, with her portion of the proceeds.[86] She and her husband kept horses, in which Colonel Kulikovsky was especially interested, along with Jersey cows, pigs, chickens, geese, dogs and cats.[87] For transport they had a small car and a sledge.[87] Tihon and Guri (age thirteen and eleven, respectively when they moved to Knudsminde) grew up on the farm. Olga ran the household with the help of her elderly, faithful lady's maid Emilia Tenso ("Mimka"), who had come along with her from Russia. The Grand Duchess lived with simplicity, working in the fields, doing household chores, and painting.[87]

The farm became a center for the Russian monarchist community in Denmark, and many Russian emigrants visited.[88] Olga maintained a high level of correspondence with the Russian émigré community and former members of the imperial army.[65] On 2 February 1935 in the Russian Orthodox Church in Copenhagen, she and her husband were godparents, with her cousin Prince Gustav of Denmark, to Aleksander Schalburg, son of Russian-born Danish army officer Christian Frederik von Schalburg.[89] In the 1930s, the family took annual holidays at Sofiero Palace, Sweden, with Crown Prince Gustaf of Sweden and his wife, Louise.[90] Olga began to sell her own paintings, of Russian and Danish scenes, with exhibition auctions in Copenhagen, London, Paris, and Berlin. Some of the proceeds were donated to the charities she supported.[65]

Neutral Denmark was invaded by Nazi Germany on 9 April 1940 and was occupied for the remainder of World War II. Food shortages, communication restrictions, and transport closures followed. As Olga's sons, Tikhon and Guri, served as officers in the Danish Army, they were interned as prisoners of war, but their imprisonment in a Copenhagen hotel lasted less than two months.[91] Tikhon was imprisoned for a further month in 1943 after being arrested on charges of espionage.[92] Other Russian émigrés, keen to fight against the Soviets, enlisted in the German forces. Despite her sons' internment and her mother's Danish origins, Olga was implicated in her compatriots' collusion with German forces, as she continued to meet and extend help to Russian émigrés fighting against communism.[93] On 4 May 1945, German forces in Denmark surrendered to the British. When economic and social conditions for Russian exiles failed to improve, General Pyotr Krasnov wrote to the Grand Duchess, detailing the wretched conditions affecting Russian immigrants in Denmark.[94] She in turn asked Prince Axel of Denmark to help them, but her request was refused.[95]

With the end of World War II, Soviet troops occupied the Danish island of Bornholm, and the Soviet Union wrote to the Danish government accusing Olga and a Danish Catholic bishop of conspiracy against the Soviet government.[96] The surviving Romanovs in Denmark grew fearful of an assassination or kidnap attempt,[97] and Olga decided to move her family across the Atlantic to the relative safety of rural Canada.[98]

Emigration to Canada

[edit]In May 1948, the Kulikovskys travelled to London by Danish troopship. They were housed in a grace and favour apartment at Hampton Court Palace while arrangements were made for their journey to Canada as agricultural immigrants.[99] On 2 June 1948, Olga, Kulikovsky, Tikhon and his Danish-born wife Agnete, Guri and his Danish-born wife Ruth, Guri and Ruth's two children, Xenia and Leonid, and Olga's devoted companion and former maid Emilia Tenso ("Mimka") departed Liverpool on board the Empress of Canada.[100] After a rough crossing, the ship docked at Halifax, Nova Scotia.[101] The family lived in Toronto, until they purchased a 200-acre (81 ha) farm in Halton County, Ontario, near Campbellville.[102][103]

By 1952, the farm had become a burden to Olga and her husband. They were both elderly; their sons had moved away; labour was hard to come by; the Colonel suffered increasing ill-health, and some of Olga's remaining jewelry was stolen.[104] The farm was sold, and Olga, her husband and her former maid, Mimka, moved to a smaller five-room house at 2130 Camilla Road, Cooksville, Ontario, a suburb of Toronto now amalgamated into Mississauga.[105] Mimka suffered a stroke that left her disabled, and Olga nursed her until Mimka's death on 24 January 1954.[106]

Neighbours and visitors to the region, including foreign and royal dignitaries, took interest in Olga, and visited her home. Among these were members of her extended family, including first cousin once removed Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent, in 1954,[107] and second cousin Louis Mountbatten, and his wife Edwina, in August 1959.[108] In June 1959, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip (a first cousin twice removed and a first cousin once removed, respectively) visited Toronto and invited the Grand Duchess for lunch on board the royal yacht Britannia.[109] Her home was also a magnet for Romanov impostors, whom Olga and her family considered a menace.[110]

By 1958, Olga's husband was virtually paralyzed, and she sold some of her remaining jewelry to raise funds.[111] Following her husband's death in 1958, she became increasingly infirm until hospitalized in April 1960 at Toronto General Hospital.[112] She was not informed[113] or was not aware[114] that her elder sister, Xenia, died in London that month. Unable to care for herself, Olga went to stay with Russian émigré friends, Konstantin and Sinaida Martemianoff, in an apartment above a beauty salon at 716 Gerrard Street East, Toronto.[115] She slipped into a coma on 21 November 1960, and died on 24 November at the age of 78.[116]

She was interred next to her husband in York Cemetery, Toronto, on 30 November 1960, after a funeral service at Christ the Saviour Cathedral, Toronto. Officers of the Akhtyrsky Hussars and the Blue Cuirassiers stood guard in the small Russian church, which overflowed with mourners.[117] Although she lived simply, bought cheap clothes, and did her own shopping and gardening, her estate was valued at more than 200,000 Canadian dollars (about C$2.03 million in 2023[118]) and was mostly held as stock and bonds.[119] Her material possessions were appraised at $350 in total, which biographer Patricia Phenix considered an underestimate.[120]

Legacy

[edit]

Olga began drawing and painting at a young age. She told her official biographer Ian Vorres:

Even during my geography and arithmetic lessons, I was allowed to sit with a pencil in my hand. I could listen much better when I was drawing corn or wild flowers.[121]

She painted throughout her life, on paper, canvas and ceramic, and her output is estimated at over 2,000 pieces.[122] Her usual subject was scenery and landscape, but she also painted portraits and still lifes. Vorres wrote,

Her paintings, vivid and sensitive, are immersed in the subdued light of her beloved Russia. Besides her numerous landscapes and flower pictures that reveal her inherent love for nature, she often also dwells on scenes from simple daily life ... executed with a sensitive eye for composition, expression and detail. Her work exudes peace, serenity and a spirit of love that mirror her own character, in total contrast to the suffering she experienced through most of her life.[122]

Her daughter-in-law wrote,

Being a deeply religious person, the Grand Duchess perceived the beauty of nature as being divinely inspired creation. Prayer and attending church provided her with the strength not only to overcome the new difficulties befallen her, but also to continue with her drawing. These feelings of gratefulness to God pervaded not only the icons created by the Grand Duchess, but also her portraits and still life paintings.[94]

Her paintings were a profitable source of income.[123] According to her daughter-in-law, Olga preferred to exhibit in Denmark to avoid the commercialism of the North American market.[124] The Russian Relief Programme, which was founded by Tikhon and his third wife Olga in honour of the Grand Duchess,[125] exhibited a selection of her work at the residence of the Russian ambassador in Washington in 2001, in Moscow in 2002, in Ekaterinburg in 2004, in Saint Petersburg and Moscow in 2005, in Tyumen and Surgut in 2006, at the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and Saint Michael's Castle in Saint Petersburg in 2007,[126] and at the Vladimir Arsenyev Museum in Vladivostok in 2013.[127] Pieces by Olga are included in the collections of the British queen Elizabeth II, the Norwegian king Harald V, and private collections in North America and Europe.[122] Ballerup Museum in Pederstrup, Denmark, has around 100 of her works.[128]

Ancestry

[edit]| Ancestors of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna of Russia |

|---|

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Vorres, p. 3

- ^ a b Phenix, pp. 8–10; Vorres, p. 4

- ^ Vorres, p. 11

- ^ Harcave, p. 32

- ^ a b Vorres, p. 12

- ^ Phenix, p. 20

- ^ Vorres, pp. 18–20

- ^ Phenix, pp. 12–13; Vorres, pp. 26–27

- ^ Vorres, p. 30

- ^ Phenix, p. 8; Vorres, p. 25

- ^ Vorres, p. 24

- ^ Vorres, pp. 9–11

- ^ Phenix, pp. 11, 24; Vorres, pp. 33–41

- ^ Vorres, pp. 48–52

- ^ Phenix, pp. 30–31; Vorres, pp. 54, 57

- ^ Vorres, p. 55

- ^ Phenix, p. 45; Vorres, pp. 72–74

- ^ a b Vorres, p. 74

- ^ a b c d Kulikovsky-Romanoff, p. 4

- ^ Belyakova, p. 86

- ^ Belyakova, p. 84

- ^ Vorres, p. 75

- ^ Phenix, p. 52

- ^ a b c d Belyakova, p. 88

- ^ Olga said: "I shared his roof for nearly fifteen years, and never once we were husband and wife" (Vorres, p. 76); see also Massie, p. 171

- ^ Vorres, pp. 75, 78

- ^ Phenix, p. 46

- ^ a b c Belyakova, p. 89

- ^ Vorres, p. 81

- ^ Vorres, pp. 78–79

- ^ a b c Kulikovsky-Romanoff, p. 3

- ^ Vorres, p. 79

- ^ Belyakova, p. 91

- ^ Crawford and Crawford, p. 51; Phenix, p. 62; Vorres, pp. 94–95

- ^ Phenix, p. 63; Vorres, p. 95

- ^ Crawford and Crawford, p. 52; Phenix, p. 73; Vorres, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Vorres, pp. 95–96

- ^ A Cuirassier's Memoirs by Vladimir Trubetskoy, quoted in Phenix, p. 73.

- ^ Vorres, pp. 97–99, 101

- ^ a b Massie, p. 171; Vorres, pp. 102–103

- ^ Phenix, p. 144; Vorres, pp. 98–99

- ^ Phenix, pp. 73–83; Vorres, pp. 127–139

- ^ Phenix, pp. 85–88; Vorres, pp. 108–109

- ^ Phenix, p. 68; Vorres, p. 111

- ^ Phenix, p. 69; Vorres, p. 111

- ^ Phenix, p. 69; Vorres, p. 112

- ^ Vorres, p. 113

- ^ Vorres, pp. 117–119

- ^ Phenix, p. 89; Vorres, pp. 121–122

- ^ Vorres, p. 122

- ^ Vorres, p. 123.

- ^ Vorres, p. 125

- ^ Phenix, pp. 91–92; Vorres, p. 141

- ^ Phenix, p. 93; Vorres, p. 143

- ^ Phenix, p. 101

- ^ Phenix, p. 103

- ^ Grand Duke Alexander's Memoirs, Once A Grand Duke, p. 273, quoted in Phenix, p. 104

- ^ Phenix, pp. 115–117; Vorres, pp. 149–150

- ^ Phenix, p. 118

- ^ Phenix, pp. 122–123; Vorres, pp. 155–156

- ^ Phenix, pp. 123–125; Vorres, pp. 156–157

- ^ e.g. Letter from King George V to Victoria, Marchioness of Milford Haven, 2 September 1918, quoted in Hough, p. 326

- ^ Phenix, p. 128; Vorres, p. 159

- ^ Phenix, p. 129

- ^ a b c d Kulikovsky-Romanoff, p. 5

- ^ Phenix, p. 132

- ^ Vorres, pp. 167–171

- ^ Beéche, p. 116

- ^ Olga quoted in Vorres, p. 173

- ^ a b c Olga quoted in Vorres, p. 175

- ^ Olga quoted in Massie, p. 174 and Vorres, p. 174

- ^ a b Olga quoted in Vorres, p. 176

- ^ "My nieces knew no German at all. Mrs. Anderson did not seem to understand a word of Russian or English, the two languages all the four sisters had spoken since babyhood.": Olga quoted in Vorres, p. 174

- ^ Klier and Mingay, p. 156; Vorres, p. 176

- ^ Klier and Mingay, p. 102; Massie, p. 174; Phenix, p. 155

- ^ Letter from Olga to Herluf Zahle, 31 October 1925, quoted in Kurth, p. 119, but with a proviso that the original letter has never been seen

- ^ Letter from Olga to Colonel Anatoly Mordvinov, 4 December 1925, Oberlandesgericht Archive, Hamburg, quoted in Kurth, p. 120

- ^ Olga wrote in a letter to Tatiana Melnik, 30 October 1926, Botkin Archive, quoted in Kurth, p. 144; and a letter dated 13 September 1926 quoted in von Nidda, pp. 197–198: "However hard we tried to recognize this patient as my niece Tatiana or Anastasia, we all came away quite convinced of the reverse." In a letter from Olga to Princess Irene, 22 December 1926, quoted in von Nidda, p. 168, she wrote, "I had to go to Berlin last autumn to see the poor girl said to be our dear little niece. Well, there is no resemblance at all, and it is obviously not Anastasia ... It was pitiful to watch this poor creature trying to prove she was Anastasia. She showed her feet, a finger with a scar and other marks which she said were bound to be recognized at once. But it was Maria who had a crushed finger, and someone must have told her this. For four years this poor creature's head was stuffed with all these stories ... It has been claimed, however, that we all recognized her and were then given instructions by Mama to deny that she was Anastasia. That is a complete lie. I believe this whole story is an attempt at blackmail."

- ^ Klier and Mingay, p. 102; Vorres, p. 177

- ^ a b c Olga quoted in Vorres, p. 177

- ^ National Tidende, 16 January 1926, quoted in Klier and Mingay, p. 102 and Phenix, p. 155

- ^ "I can swear to God that I did not receive before or during my visit to Berlin, either a telegram or a letter from my sister Xenia advising that I should not acknowledge the stranger.": Sworn testimony of Grand Duchess Olga, Staatsarchiv Hamburg, File 1991 74 0 297/57 Volume 7, pp. 1297–1315, quoted in Phenix, p. 238

- ^ "They state that we all recognized her and that we then received an order from Mama to say that she is not Anastasia. This is a great lie!": Letter from Olga to Princess Irene, quoted in Klier and Mingay, p. 149

- ^ Phenix, p. 238

- ^ Xenia to Michael Thornton, quoted in a letter from Thornton to Patricia Phenix, 10 January 1998, quoted in Phenix, pp. 237–238

- ^ Phenix, p. 168; Vorres, p. 185.

- ^ a b c Hall, p. 58.

- ^ Phenix, p. 170.

- ^ "Fødte Mandkøn" [Born Males]. Kirkebog [Parish Register]. 1915–1945 (in Danish). Den Ortodokse Russiske Kirke i København. 1934. p. 14.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Vorres, p. 186.

- ^ Phenix, p. 174.

- ^ Phenix, p. 176

- ^ Phenix, p. 176; Vorres, p. 187.

- ^ a b Kulikovsky-Romanoff, p. 6

- ^ Phenix, p. 178.

- ^ Phenix, p. 179.

- ^ Phenix, pp. 179–180; Vorres, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Mr. J. S. P. Armstrong, Agent General for Ontario, quoted in Vorres, p. 191.

- ^ Vorres, pp. 188, 190

- ^ Vorres, p. 193

- ^ Vorres, p. 196

- ^ Vorres, pp. 196–198

- ^ "Allison Farm in Nassagaweya Is for Russian Nobility". The Canadian Champion. Milton. 15 July 1948. p. 1.

- ^ Vorres, pp. 207–208

- ^ Phenix, pp. 205–206; Vorres, p. 209

- ^ Phenix, p. 207; Vorres, p. 210

- ^ Phenix, p. 214; Vorres, p. 211

- ^ Vorres, p. 221

- ^ Phenix, pp. 238–239; Vorres, p. 207

- ^ Vorres, pp. 200–205

- ^ Vorres, p. 219

- ^ Phenix, pp. 240–242; Vorres, p. 224

- ^ Vorres, p. 225

- ^ Phenix, p. 242

- ^ Phenix, p. 243; Vorres, p. 226

- ^ Vorres, p. 227

- ^ Phenix, pp. 246–247; Vorres, pp. 228–230

- ^ 1688 to 1923: Geloso, Vincent, A Price Index for Canada, 1688 to 1850 (December 6, 2016). Afterwards, Canadian inflation numbers based on Statistics Canada tables 18-10-0005-01 (formerly CANSIM 326-0021) "Consumer Price Index, annual average, not seasonally adjusted". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 17 April 2021. and table 18-10-0004-13 "Consumer Price Index by product group, monthly, percentage change, not seasonally adjusted, Canada, provinces, Whitehorse, Yellowknife and Iqaluit". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ Phenix, p. 249

- ^ Phenix, p. 250

- ^ Vorres, p. 26

- ^ a b c Vorres, Ian (2000) "After the Splendor... The Art of the Last Romanov Grand Duchess of Russia" Archived 12 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Smithsonian Institution, retrieved 9 March 2013

- ^ Grand Duchess Olga, quoted in Kulikovsky-Romanoff, p. 7

- ^ Kulikovsky-Romanoff, p. 8

- ^ Phenix, p. 1

- ^ "Majestic Artist: 125th birth anniversary of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna" Archived 21 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Russian State Museum, retrieved 9 March 2013

- ^ Gilbert, Paul (16 January 2013) "Exhibition of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna's Watercolours Opens in Vladivostok" Archived 12 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Royal Russia News, retrieved 9 March 2013

- ^ Ballerup Museum Archived 12 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 9 March 2013

References

[edit]- Beéche, Arturo (ed.) (2004) The Grand Duchesses. Oakland: Eurohistory. ISBN 0-9771961-1-9

- Belyakova, Zoia (2010) Honour and Fidelity: The Russian Dukes of Leuchtenberg. Saint Petersburg: Logos Publishers. ISBN 978-5-87288-391-3

- Crawford, Rosemary; Crawford, Donald (1997) Michael and Natasha: The Life and Love of the Last Tsar of Russia. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-7538-0516-9

- Hall, Coryne (1993) The Grand Duchess of Knudsminde. Article published in Royalty History Digest.

- Harcave, Sidney (2004) Count Sergei Witte and the Twilight of Imperial Russia: A Biography. New York: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1422-3

- Hough, Richard (1984) Louis and Victoria: The Family History of the Mountbattens. Second edition. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-78470-6

- Klier, John; Mingay, Helen (1995) The Quest for Anastasia. London: Smith Gryphon. ISBN 1-85685-085-4

- Kulikovsky-Romanoff, Olga (Undated) "The Unfading Light of Charity: Grand Duchess Olga As a Philanthropist And Painter", Historical Magazine, Gatchina, Russia: Gatchina Through The Centuries, retrieved 6 March 2010

- Kurth, Peter (1983) Anastasia: The Life of Anna Anderson. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-02951-7

- Massie, Robert K. (1995) The Romanovs: The Final Chapter. London: Random House. ISBN 0-09-960121-4

- Phenix, Patricia (1999) Olga Romanov: Russia's Last Grand Duchess. Toronto: Viking/Penguin. ISBN 0-14-028086-3

- von Nidda, Roland Krug (1958) Commentary in I, Anastasia: An autobiography with notes by Roland Krug von Nidda translated from the German by Oliver Coburn. London: Michael Joseph.

- Vorres, Ian (2001) [1964] The Last Grand Duchess. Toronto: Key Porter Books. ISBN 1-55263-302-0

External links

[edit]

- 1882 births

- 1960 deaths

- 19th-century women from the Russian Empire

- People from Petergof

- People from Petergofsky Uyezd

- Grand duchesses of Russia

- Duchesses of Oldenburg

- House of Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov

- Philanthropists from the Russian Empire

- Russian women philanthropists

- White movement people

- Russian women in World War I

- Female wartime nurses

- Painters from the Russian Empire

- Russian women painters

- Russian icon painters

- White Russian emigrants to Denmark

- Danish emigrants to Canada

- Grand Crosses of the Order of St. Sava

- Daughters of Russian emperors

- Burials at York Cemetery, Toronto

- Nurses from the Russian Empire

- Children of Alexander III of Russia

- Daughters of dukes