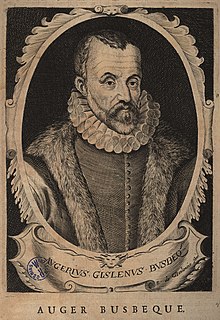

Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq

Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq (1522 in Comines – 29 October 1592 in Saint-Germain-sous-Cailly; Latin: Augerius Gislenius Busbequius), sometimes Augier Ghislain de Busbecq, was a 16th-century Flemish writer, herbalist and diplomat in the employ of three generations of Austrian monarchs. He served as ambassador to the Ottoman Empire in Constantinople and in 1581 published a book about his time there, Itinera Constantinopolitanum et Amasianum, re-published in 1595 under the title of Turcicae epistolae or Turkish Letters. His letters also contain the only surviving word list of Crimean Gothic, a Germanic dialect spoken at the time in some isolated regions of Crimea. He is credited with the introduction of tulips into Western Europe and to the origin of their name.

Early years

[edit]

He was born the illegitimate son of the Seigneur de Busbecq, Georges Ghiselin, and his mistress Catherine Hespiel, although he was later legitimized.[1] He grew up at Busbecq Castle (in present-day Bousbecque, Nord, France), studying in Wervik and Comines, which at the time were all part of Spanish West Flanders, a province of the Holy Roman Empire.

Busbecq's intellectual gifts led him to advanced studies at the Latin-language University of Leuven, where he registered in 1536 under the name Ogier Ghislain de Comines. From there, he went on to study at a number of well-known universities in northern Italy, including taking classes from Giovanni Battista Egnazio in Venice.

Like his father and grandfather, Busbecq chose a career of public service. He started work in the court of the later Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I in approximately 1552. In 1554, he was sent to England for the marriage in Winchester of the English queen Mary Tudor to Philip II of Spain.

At the Ottoman court

[edit]In 1554 and again in 1556,[1] Ferdinand named Busbecq ambassador to the Ottoman Empire under the rule of Suleiman the Magnificent. His task for much of the time he was in Constantinople was the negotiation of a border treaty between his employer (the future Holy Roman Emperor) and the Sultan over the disputed territory of Transylvania. He had no success in this mission while Rüstem Pasha was the Sultan's vizier, but ultimately reached an accord with his successor Semiz Ali Pasha.

During his stay in Constantinople, Busbecq wrote his best known work, the Turkish Letters, a compendium of personal correspondence to his friend, and fellow Hungarian diplomat, Nicholas Michault, in Flanders and some of the world's first travel literature. These letters, together with Melchior Lorck's woodprints describe his adventures in Ottoman politics and remain one of the principal primary sources for students of the 16th-century Ottoman court. He also wrote in enormous detail about the plant and animal life he encountered in Turkey. His letters also contain the only surviving word list of Crimean Gothic, a Germanic dialect spoken at the time in some isolated regions of Crimea.[2]

Busbecq discovered an almost complete copy of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, an account of Roman emperor Augustus' life and accomplishments, at the Monumentum Ancyranum in Ancyra. He identified its origin from his reading of Suetonius and published a copy of parts of it in his Turkish Letters.[3]

He was an avid collector, acquiring valuable manuscripts, rare coins and curios of various kinds. Among the best known of his discoveries was a 6th-century copy of Dioscorides' De Materia Medica, a compendium of medicinal herbs. The emperor purchased it after Busbecq's recommendation; the manuscript is now known as the Vienna Dioscorides. His passion for herbalism led him to send Turkish tulip bulbs to his friend Charles de l'Écluse, who acclimatized them to life in the Low Countries. He called them "tulip", mistaking the Turkish word for turban (tulipant) which was often decorated with the flower (known in Turkish as lale).[4] Busbecq has also been credited with introducing the lilac to northern Europe (though this is debated)[2] as well as the Angora goat.[1]

Life after Turkey

[edit]He returned from Turkey in 1562 and became a counsellor at the court of Emperor Ferdinand in Vienna and tutor to his grandchildren, the sons of future Emperor Maximilian II. Busbecq ended his career as the guardian of Elisabeth of Austria, Maximilian's daughter and widow of French king Charles IX. He continued to serve the Austrian monarchy, observing the development of the French Wars of Religion on behalf of Rudolf II. Finally, in 1592 and nearing the end of his life, he chose to leave his residence in Mantes outside of Paris for his native West Flanders, but was assaulted and robbed by members of the Catholic League near Rouen. He died a few days later. His body is buried in the castle chapel at Saint-Germain-sous-Cailly near where he died, and his heart was embalmed and sent to the family tomb in Bousbecque.

Bibliography

[edit]- Itinera Constantinopolitanum et Amasianum (1581), later published as A. G. Busbequii D. legationis Turcicae epistolae quattor - Known in English as Turkish Letters. An early 20th-century English translation is available as ISBN 0-8071-3071-0.

- Epistolae ad Rudolphum II. Imperatorem e Gallia scriptae (1630) – Posthumous publication of Busbecq's letters to Rudolf II detailing the life and politics of the French court.

- Vier brieven over het gezantschap naar Turkije (Legationis Turcicae epistolae quatuor), Ogier Ghiselin van Boesbeeck. Translation Michel Goldsteen, Introduction and Notes Zweder von Martels. Available ISBN 90-6550-007-3 (uitgeverij Verloren, Hilversum, Netherlands)

- Les écritures de l'ambassade: les Lettres turques d'Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq. Traduction annotée et étude littéraire. PhD Thesis of Dominique ARRIGHI, Sorbonne, Paris, 2006.

- Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq. Les Lettres Turques, translation into French by Dominique ARRIGHI, Honoré Champion, Champion Classiques collection, ISBN 978-2-7453-2038-4, introduction by Gilles Veinstein, Ottoman history professor at Collège de France.

- translated into English as, The Life and Letters of Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, 1881, by Forster and Daniell available on-line free Vol 1 Vol 2

- Turkish Letters, English, translated by E.S. Forster. Eland Books (2005) ISBN 0-907871-69-0

See also

[edit]- Manuscripts Busbecq brought from Constantinople: Minuscule 218, Minuscule 222, Minuscule 421, Minuscule 434, Minuscule 425, Minuscule 719, Minuscule 722

- List of Austrian ambassadors to Turkey

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Busbecq, Augier Ghislain de. (2009). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 28, 2009, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://search.eb.com/eb/article-9018254

- ^ a b Considine, John (2008). Dictionaries in early modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 139–140. ISBN 9780521886741.

- ^ Edward Seymour Forster, translator, The Turkish Letters of Ogier de Busbecq reprinted Louisiana State University 2005.

- ^ Hernández Bermejo, J. Esteban; García Sánchez, Expiración (2009). "Tulips: An Ornamental Crop in the Andalusian Middle Ages". Economic Botany. 63 (1): 60–66. doi:10.1007/s12231-008-9070-3. ISSN 0013-0001. S2CID 25071279.