Odanak

Odanak | |

|---|---|

Saint-François-de-Sales church | |

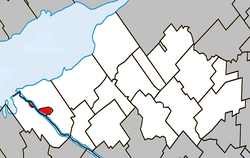

Location within Nicolet-Yamaska RCM | |

| Coordinates: 46°04′N 72°50′W / 46.067°N 72.833°W[1] | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Region | Centre-du-Québec |

| RCM | None |

| Constituted | unspecified |

| Government | |

| • Type | Band council |

| • Federal riding | Bas-Richelieu—Nicolet—Bécancour |

| • Prov. riding | Nicolet-Bécancour |

| Area | |

• Total | 5.70 km2 (2.20 sq mi) |

| • Land | 5.61 km2 (2.17 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Total | 481 |

| • Density | 85.8/km2 (222/sq mi) |

| • Dwellings | 243 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Area code | 450 |

| Access Routes[5] | |

Odanak is an Abenaki First Nations reserve in the Central Quebec region, Quebec, Canada. The mostly First Nations population as of the 2021 Canadian census was 481. The territory is located near the mouth of the Saint-François River at its confluence with the St. Lawrence River. It is partly within the limits of Pierreville and across the river from Saint-François-du-Lac. Odanak is an Abenaki word meaning "in the village".

History

[edit]Beginning about 1000 CE, Iroquoian-speaking people settled along the St. Lawrence River, where they practiced agriculture along with hunting and fishing. Archeological surveys have revealed that by 1300, they built fortified villages similar to those seen and described by French explorer Jacques Cartier in the mid-16th century, when he visited Hochelaga and Stadacona. However, by 1600, the villages and people were gone. Since the 1950s, historians and anthropologists have used archeological and linguistic evidence to develop a consensus that the people formed a distinct ethnic group, whom they have called St. Lawrence Iroquoians. They spoke Laurentian and were separate from the powerful Iroquois Confederacy of nations that developed in present-day New York and Pennsylvania along the southern edges of the Great Lakes.[6]

Their disappearance by 1600 is believed to be due to attacks and decimation from the Mohawk people of the Iroquois Confederacy; they stood to gain the most by getting control of the hunting grounds along the St. Lawrence River and dominating the fur trade route on the river above Tadoussac, which was under Montagnais control. By the time of Samuel de Champlain's arrival, the St. Lawrence River Valley was essentially uninhabited; the Mohawk reserved it for use as hunting grounds and as a path for war parties.[6]

As French missionaries worked in present-day Quebec and central-western New York with native peoples in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, they established mission villages for converted natives near the colonial towns of Quebec City and Montreal. The Abenaki who converted to Catholicism were allied with the French. Evidence supports the tradition that St. Francis was first occupied by the Sokoki (Ozogwakiakas in Abenaki) as early as 1660, with as many as twenty families; the earliest Sokoki baptism recorded in the area was nearby in Trois-Rivières in 1658. The Sokoki were a band or tribe within the larger Abenaki group. Central Maine was formerly inhabited by people of the Androscoggin people, also known as Arosaguntacook. The Androscoggin were a tribe in the Abenaki nation.

They were driven out of the area by Europeans in 1690 sometime after King Philip's War (1675–1676). They were relocated west at St. Francis, Canada. During the French and Indian War (the Seven Years' War), this settlement was destroyed and burnt by Rogers' Rangers in 1759. The Abenaki and some St. Francis residents participated in raids against English settlements. These were sometimes organized by Sébastien Rale and Abenaki chief Grey Lock in Dummer's War along the frontiers of New England in the early 18th century. Other Abenaki tribes suffered several severe defeats in reprisal during Father Rale's War, particularly the capture of Norridgewock in 1724 and the defeat of the Pequawket in 1725, which greatly reduced their numbers.

Odanak was first established in the year 1700. While traveling along the banks of the St. François River the Jesuit Priest Jacques Bigot made the decision to relocate the Jesuit mission "La Mission de Saint François de Sale" that was established in 1684 at the mouth of the Chaudière River to the banks of the St. François River following years of successive crop failure due to agricultural overexploitation.[7] The new mission was to be established in close proximity to a small village of both Abenaki and Sokokis that Bigot had previously observed during his travels throughout the region in the winter of 1684–1685.[8] At the request of the Governor General of New France Louis-Hector de Callière and the Intendant Jean Bochart de Champigny, Marguerite Hertel the widow of Jean Crevier de Saint-François and her son Joseph Crevier granted one "demi lieu" of land from their seigneury to the Abenakis which was accepted on behalf of Bigot on which the new mission was to be constructed.[9]

In 1704, the King Louis XIV of France ordered the King's Engineer, Levasseur De Néré to draw up a plan in order fortify the Jesuit mission during the War of the Spanish Succession to provide protection for the families of the Abenaki and Sokoki warriors who had sided with the French against the English and the Iroquois during the war and in prior conflicts. Governor Callière subsequently ordered the construction of defensive features such as redoubts and a 4.7 m high palisade that was to be reinforced with stone bastions.[10] During this war, Abenaki warriors were involved in numerous raids and conflicts such as the infamous Deerfield Raid of 29 February 1704 in which 112 English captives were taken.[11]

In 1706, the village was moved from its original location on the north-eastern bank of the St. François River downstream, near the current location of Pierreville in order to accommodate a growing population. In the summer of 1711, Odanak was temporarily abandoned due to the threats posed by Admiral Hovenden Walker's and Colonel Francis Nicholson's planned assault on Quebec City. The male Abenaki warriors of the village were called up to Quebec to take part in the defence of the city while the woman and children were temporarily relocated to Trois-Rivières and Montreal. Following the failure and withdrawal of Admiral Walker's fleet, the Abenaki would once again return to Odanak.[12] In 1715, the village would be relocated once more. This time moving further downstream to the site of its current location situated high upon the bank of the St. François River to protect against seasonal flooding.[13]

Following the conclusion of Dummer's War in 1725, Odanak would be further reinforced by the arrival of a contingent of 300 Abenaki warriors and their families from the Narransouac and Pentagouet missions in Maine.

On 4 October 1759, Odanak was sacked and destroyed by a contingent of 200 men under the command of Major Robert Rogers. Rogers was ordered by Jeffery Amherst to seek retaliation for numerous raids and attacks perpetrated by Abenaki warriors on British settlements. Rogers was able to take advantage of the absence of the majority of Abenaki warriors who were serving under the command of French General Montcalm in the defense of Quebec City.[14] Rogers men subsequently destroyed and set fire to entirety of the village destroying the mission's records and archives. Casualty estimates from this attack vary considerably depending on the accounts with Roger's claiming 200 dead and 20 captives (both women and children) while French accounts claim 30 dead, 20 of whom were identified as being women and children.[15] This would mark the last major event that took place during the era of New France.

Demographics

[edit]

Population

[edit]Population estimates prior to 1759 are difficult due to the loss of records associated with the raid conducted by Major Rogers on 4 October 1759.

Population trend:[16]

| Census | Population | Change (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 481 | |

| 2016 | 449 | |

| 2011 | 457 | |

| 2006 | 469 | |

| 2001 | 425 | |

| 1996 | 392 | |

| 1991 | 333 | |

| 1986 | 262 | |

| 1981 | 228 | |

| 1976 | 228 | |

| 1971 | 215 | |

| 1966 | 239 | |

| 1961 | 216 | |

| 1956 | 250 | |

| 1951 | 225 | |

| 1941 | 308 | |

| 1931 | 315 | |

| 1921 | 342 | N/A |

| 1749 | 200 warriors + families[17] | N/A |

| 1711 | 260 warriors + families[18] or 300 inhabitants + 260 warriors[19] | N/A |

| 1698 | 335 (census of mission prior to relocation) | N/A |

Language

[edit]Mother tongue language (2021)[20]

| Language | Population | Pct (%) |

|---|---|---|

| French only | 435 | 90.6% |

| English only | 35 | 7.3% |

| Both English and French | 5 | 1% |

| Other languages | 5 | 1% |

Arts and culture

[edit]Odanak is the site of the Musée des Abénakis (Abenaki Museum), dedicated to the history, culture, and art of the Western Abenaki people.

Alanis Obomsawin (Abenaki), is a filmmaker who grew up in Odanak. Her documentary, Waban-Aki: People from Where the Sun Rises[21] (2006) is a tribute to the people of St. Francis. Her most recent documentary film Gene Boy Came Home (2007) tells the story of Eugene "Gene Boy" Benedict. He was raised in Odanak. As a young man, he fought in the US Marine Corps against the North Vietnamese in the Vietnam War before returning to his home village.

Education

[edit]In 2011, the only First Nations CEGEP in Québec opened its doors in Odanak.

Notable people

[edit]- Alanis Obomsawin (born 1932), filmmaker, musician, singer[22]

- Christine Sioui-Wawanoloath, writer and artist living in Quebec[23]

- Elijah Tahamont (1855–1918), silent film actor Dark Cloud[24]

- Alexis Wawanoloath, member of National Assembly of Quebec[25]

- Michelle O'Bonsawin, first Indigenous Supreme Court Justice in Canadian history[26][27]

- Mali Obomsawin, musician, community organizer

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Banque de noms de lieux du Québec: Reference number 45182". toponymie.gouv.qc.ca (in French). Commission de toponymie du Québec.

- ^ a b Ministère des Affaires municipales, des Régions et de l'Occupation du territoire: Odanak

- ^ "Parliament of Canada Federal Riding History: BAS-RICHELIEU--NICOLET--BÉCANCOUR (Quebec)". Archived from the original on 2009-06-09. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ a b 2021 Statistics Canada Census Profile: Odanak

- ^ Official Transport Quebec Road Map

- ^ a b James F. Pendergast. (1998). "The Confusing Identities Attributed to Stadacona and Hochelaga", Journal of Canadian Studies, Volume 32, pp. 149-156, accessed 3 Feb 2010

- ^ Day, Gordon M. The identity of the Saint Francis Indians. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada, 1981. p.5.

- ^ Treyvaud, Geneviève and Michel Plourde. The Abenakis of Odanak, an Archaeological Journey. Quebec: Marquis, 2017.p.45.

- ^ Charland, Thomas Marie. Histoire des Abénakis d'Odanak (1675-1937). Montréal: Éditions du Lévrier, 1964. p.23.

- ^ Treyvaud, Geneviève and Michel Plourde. The Abenakis of Odanak, an Archaeological Journey. Quebec: Marquis, 2017.p.86.

- ^ Haefeli, Evan, and Kevin Sweeney Captors and captives: the 1704 French and Indian raid on Deerfield. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003. p.7.

- ^ Charland, Thomas Marie. Histoire des Abénakis d'Odanak (1675-1937). Montréal: Éditions du Lévrier, 1964. p.51.

- ^ Day, Gordon M. The identity of the Saint Francis Indians. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada, 1981. p.35.

- ^ Treyvaud, Geneviève and Michel Plourde. The Abenakis of Odanak, an Archaeological Journey. Quebec: Marquis, 2017. p.50.

- ^ Day, Gordon M. The identity of the Saint Francis Indians. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada, 1981. p.42.

- ^ Statistics Canada: 1996, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016, 2021 census

- ^ Day, Gordon M. The identity of the Saint Francis Indians. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada,1981. p.41.

- ^ Treyvaud, Geneviève and Michel Plourde. The Abenakis of Odanak, an Archaeological Journey. Quebec: Marquis, 2017. p.48.

- ^ Sévigny, Andrée. Les Abénaquis: habitat et migrations, 17e et 18e siècles. Montréal: Bellarmin, 1976

- ^ 2021 Statistics Canada Community Profile: Odanak

- ^ National Film Board of Canada

- ^ Voyageur, Cora J.; Beavon, Dan; Newhouse, Davud (2011). Hidden in Plain Sight Contributions of Aboriginal Peoples to Canadian Identity and Culture, Volume II. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781442663374.

- ^ "Christine Sioui Wawanoloath" (in French). Terres en vues/Land InSights. Archived from the original on 2016-08-13.

- ^ Chamberlain, Alexander F. (April 1903). "Algonkian Words in American English: A Study in the Contact of the White Man and the Indian". The Journal of American Folklore. 16 (61). American Folklore Society: 128–129. doi:10.2307/533199. JSTOR 533199.

- ^ "Biography of Alexis Wawanoloath". Dictionnaire des parlementaires du Québec de 1792 à nos jours (in French). National Assembly of Quebec.

- ^ Canada, Supreme Court of (2001-01-01). "Supreme Court of Canada - Biography - Michelle O'Bonsawin". www.scc-csc.ca. Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^ Boisvert, Nick (19 Aug 2022). "Michelle O'Bonsawin becomes 1st Indigenous person nominated to Supreme Court of Canada". CBC News. Retrieved 19 Aug 2022.

External links

[edit]- Conseil des Abénakis d'Odanak, official website

- Waban-Aki Nation, Quebec

- (in French) Abenaki Museum, Odanak, Quebec

- Map of Odanak (Google Maps)