Great Disappointment

| Part of a series on |

| Adventism |

|---|

|

|

|

The Great Disappointment in the Millerite movement was the reaction that followed Baptist preacher William Miller's proclamation that Jesus Christ would return to the Earth by 1844, which he called the Second Advent. His study of the Daniel 8 prophecy during the Second Great Awakening led him to conclude that Daniel's "cleansing of the sanctuary" was cleansing the world from sin when Christ would come, and he and many others prepared. When Jesus did not appear by October 22, 1844, Miller and his followers were disappointed.[1][2][3][4]

These events paved the way for the Adventists who formed the Seventh-day Adventist Church. They contended that what had happened on October 22 was not Jesus's return, as Miller had thought, but the start of Jesus's final work of atonement, the cleansing in the heavenly sanctuary, leading up to the Second Coming.[1][2][3][4]

Miller's apocalyptic claims

[edit]Between 1831 and 1844, on the basis of his study of the Bible, and particularly the prophecy of Daniel 8:14[5]—"Unto two thousand and three hundred days; then shall the sanctuary be cleansed"—William Miller, a rural New York farmer and Baptist lay preacher, predicted and preached the return of Jesus Christ to the earth. Miller's teachings form the theological foundation of Seventh-day Adventism. Four topics were especially important:

- Miller's use of the Bible;

- his eschatology;

- his perspective on the first and second angel's messages of Revelation 14; and;

- the seven-month movement that ended with the "Great Disappointment".[6]

Miller's use of the Bible

[edit]Miller's approach was thorough and methodical, intensive and extensive. His central principle for interpreting the Bible was that "all scripture is necessary" and that no part should be bypassed. To understand a doctrine, Miller said one needed to "bring all scriptures together on the subject you wish to know; then let every word have its proper influence, and if you can form your theory without a contradiction you cannot be in error." He held that the Bible should be its own expositor. By comparing scripture with scripture a person could unlock the meaning of the Bible. In that way the Bible became a person's authority, whereas if a creed of other individuals or their writings served as the basis of authority, then that external authority became central rather than the teaching of the Bible itself.[7] Miller's guidelines concerning the interpretation of Bible prophecy was built upon the same concepts set forth in his general rules. The Bible, so far as Miller and his followers were concerned, was the supreme authority in all matters of faith and doctrine.[8]

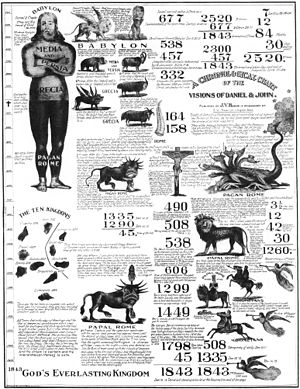

Second Advent

[edit]The Millerite movement was primarily concerned with the return of Jesus, literally, visually, in the clouds of heaven. The French Revolution was one of several factors that caused many Bible students around the world who shared Miller's concerns to delve into the time prophecies of Daniel using the historicist methodology of interpretation. They concluded, to their satisfaction, that the end of the 1,260-"day" prophecy of Daniel 7:25[9] in 1798 started the era of "time of the end". They next considered the 2,300 "days" of Daniel 8:14.[10]

There were three things that Miller determined about this text:[11]

- that the 2,300 symbolic days represented 2,300 real years, as evidenced in Ezekiel 4:6[12] and Numbers 14:34;[13]

- that the sanctuary represents the earth or church; and

- by referring to 2 Peter 3:7,[14] that the 2,300 years ended with the burning of the earth at the Second Advent.

Miller tied the 2,300-day vision to the Prophecy of Seventy Weeks in Daniel 9 where a beginning date is given. He concluded that the 70 weeks (or 70 sevens, or 490 days) were the first 490 years of the 2,300 years. The 490 years were to begin with the command to rebuild and restore Jerusalem. The Bible records four decrees concerning Jerusalem after the Babylonian captivity:

- 536 BC: Decree by Cyrus to rebuild the temple.[15]

- 519 BC: Decree by Darius I to finish the temple.[16]

- 457 BC: Decree by Artaxerxes I of Persia.[17]

- 444 BC: Decree by Artaxerxes to Nehemiah to finish the wall at Jerusalem.[18]

The decree by Artaxerxes empowered Ezra to ordain laws and to set up magistrates and judges for the restored Jewish state. It also gave him unlimited funds to rebuild whatever he wanted at Jerusalem.[19]

Miller concluded that 457 BC was the beginning of the 2,300-day (or -year) prophecy, which meant that it would end about 1843–1844 (457 BC + 2300 years = 1843 AD). And so, too, the Second Advent would happen about that time.[11]

Miller assumed that the "cleansing of the sanctuary" represented purification of the earth by fire at Christ's Second Coming. Using an interpretive principle known as the day-year principle, Miller, along with others, interpreted a prophetic "day" to read not as a 24-hour period, but rather a calendar year. Miller became convinced that the 2,300-day period started in 457 BC, the date of the decree to rebuild Jerusalem by Artaxerxes I of Persia. His interpretation led Miller to believe—and predict, despite urging of his supporters—that Christ would return in "about 1843". Miller narrowed the time period to sometime in the Jewish year 5604, stating: "My principles in brief, are, that Jesus Christ will come again to this earth, cleanse, purify, and take possession of the same, with all the saints, sometime between March 21, 1843, and March 21, 1844."[20] March 21, 1844, passed without incident, but the majority of Millerites maintained their faith.[citation needed]

After further discussion and study, Miller briefly adopted a new date—April 18, 1844—one based on the Karaite Jewish calendar (as opposed to the Rabbinic calendar).[21] Like the previous date, April 18 passed without Christ's return. In the Advent Herald of April 24, Joshua Himes wrote that all the "expected and published time" had passed and admitted that they had been "mistaken in the precise time of the termination of the prophetic period". Josiah Litch surmised that the Adventists were probably "only in error relative to the event which marked its close". Miller published a letter "To Second Advent Believers," writing, "I confess my error, and acknowledge my disappointment; yet I still believe that the day of the Lord is near, even at the door."[22]

In August 1844, at a camp meeting in Exeter, New Hampshire, Samuel S. Snow presented a new interpretation, which became known as the "seventh-month message" or the "true midnight cry". In a complex discussion based on scriptural typology, Snow presented his conclusion (still based on the 2,300-day prophecy in Daniel 8:14) that Christ would return on "the tenth day of the seventh month of the present year, 1844".[23] Using the calendar of the Karaite Jews, he determined this date to be October 22, 1844. This "seventh-month message" "spread with a rapidity unparalleled in the Millerites experience" amongst the general population.[citation needed]

October 22, 1844

[edit]October 22 passed without incident, resulting in feelings of disappointment among many Millerites.[24] Henry Emmons, a Millerite, later wrote,

I waited all Tuesday [October 22] and dear Jesus did not come;—I waited all the forenoon of Wednesday, and was well in body as I ever was, but after 12 o'clock I began to feel faint, and before dark I needed someone to help me up to my chamber, as my natural strength was leaving me very fast, and I lay prostrate for 2 days without any pain—sick with disappointment.[25]

Repercussions

[edit]

The Millerites had to deal with their own shattered expectations, as well as considerable criticism and even violence from the public. Many followers had given up their possessions in expectation of Christ's return. On November 18, 1844, Miller wrote to Himes about his experiences:

Some are tauntingly enquiring, 'Have you not gone up?' Even little children in the streets are shouting continually to passersby, 'Have you a ticket to go up?' The public prints, of the most fashionable and popular kind [...] are caricaturing in the most shameful manner of the 'white robes of the saints,' Revelation 6:11,[26] the 'going up,' and the great day of 'burning.' Even the pulpits are desecrated by the repetition of scandalous and false reports concerning the 'ascension robes', and priests are using their powers and pens to fill the catalogue of scoffing in the most scandalous periodicals of the day.[27]

There were also the instances of violence: a Millerite church was burned in Ithaca, New York, and two were vandalized in Dansville and Scottsville. In Loraine, Illinois, a mob attacked the Millerite congregation with clubs and knives, while a group in Toronto was tarred and feathered. Shots were fired at another Canadian group meeting in a private house.[28]

Both Millerite leaders and followers were left generally bewildered and disillusioned. Responses varied: some continued to look daily for Christ's return, while others predicted different dates—among them April, July, and October 1845. Some theorized that the world had entered the seventh millennium—the "Great Sabbath", and that therefore, the saved should not work. Others acted as children, basing their belief on Jesus' words in Mark 10:15:[29] "Truly, I say to you, whoever does not receive the kingdom of God like a child shall not enter it." Millerite O. J. D. Pickands used Revelation 14:14–16[30] to teach that Christ was now sitting on a white cloud and must be prayed down. It has been speculated[by whom?] that the majority simply gave up their beliefs and attempted to rebuild their lives. Some members rejoined their previous denominations. A substantial number joined the Shakers.[31]

By mid-1845, doctrinal lines among the various Millerite groups began to solidify, and the groups emphasized their differences, in a process George R. Knight terms "sect building". During this time, there were three main Millerite groups—in addition to those who had simply given up their beliefs.[32]

The first major division of the Millerite groups who retained a belief in Christ's Second Advent were those who focused on the "shut-door" belief. Popularized by Joseph Turner, this belief was based on a key Millerite passage, Matthew 25:1–13;[33] the Parable of the Ten Virgins.[34]

The shut door mentioned in Matthew 25:11–12[35] was interpreted as the close of probation. As Knight explains, "After the door was shut, there would be no additional salvation. The wise virgins (true believers) would be in the kingdom, while the foolish virgins and all others would be on the outside."[36]

The widespread acceptance of the shut-door belief lost ground as doubts were raised about the significance of the October 22, 1844, date—if nothing happened on that date, then there could be no shut door. The opposition to these shut-door beliefs was led by Himes and make up the second post-1844 group. This faction soon gained the upper hand, even converting Miller to their point of view. Their influence was enhanced by the staging of the Albany Conference. The Advent Christian Church has its roots in this post-Great Disappointment group.[citation needed]

The third major post-disappointment Millerite group also claimed, like the Hale- and Turner-led group, that the October 22 date was correct. Rather than Christ having returned invisibly, however, they concluded that the event that took place on October 22, 1844, was quite different. The theology of this third group appears to have had its beginnings as early as October 23, 1844—the day after the Great Disappointment. On that day, during a prayer session with a group of Advent believers, Hiram Edson became convinced that "light would be given" and their "disappointment explained".[37]

Edson's experience led him into an extended study on the topic with O. R. L. Crosier and F. B. Hahn. They came to the conclusion that Miller's assumption that the sanctuary represented the earth was in error. "The sanctuary to be cleansed in Daniel 8:14 was not the earth or the church, but the sanctuary in heaven."[38] Therefore, the October 22 date marked not the Second Coming of Christ, but rather a heavenly event. Out of this third group arose the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and this interpretation of the Great Disappointment forms the basis for the Seventh-day Adventist doctrine of the pre-Advent Divine Investigative Judgement. Their interpretations were published in early 1845 in the Day Dawn.

Connection to the Baháʼí Faith

[edit]Members of the Baháʼí Faith believe that Miller's interpretation of signs and dates of the coming of Jesus were, for the most part, correct.[39] They believe that the fulfillment of biblical prophecies of the coming of Christ came through a forerunner of their own religion, the Báb, who declared that he was the "Promised One" on May 23, 1844, and began openly teaching in Persia in October 1844.[40][41] Several Baháʼí books and pamphlets make mention of the Millerites, the prophecies used by Miller and the Great Disappointment, most notably Baháʼí follower William Sears' Thief in the Night.[42][43][44]

It was noted that the year AD 1844 was also the Year AH 1260. Sears tied Daniel's prophecies in with the Book of Revelation in the New Testament in support of Baháʼí teaching, interpreting the year 1260 as the "times, time and half a time" of Daniel 7:25 (3 and 1/2 years = 42 months = 1,260 days). Using the same day-year principle as did William Miller, Sears decoded these texts into the year AH 1260, or 1844.[42]

It is believed by Baháʼís that if William Miller had known the year 1844 was also the year AH 1260, then he may have considered that there were other signs to look for. The Baháʼí interpretation of chapters 11 and 12 of the Book of Revelation, together with the predictions of Daniel, were explained by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the son of the founder of the Baháʼí Faith, to Laura Clifford Barney and published in 1908 in Chapters 10, 11 and 13 of "Some Answered Questions". The explanation provided in Chapter 10 draws on the same biblical verses that William Miller used, and comes to the same conclusion about the year in which to expect the 'cleansing of the sanctuary' which was interpreted by 'Abdu'l-Bahá to be the 'dawn' of a new 'Revelation' – AD 1844.[citation needed]

Other views

[edit]The Great Disappointment is viewed by some scholars as an example of the psychological phenomenon of cognitive dissonance.[45] The theory was proposed by Leon Festinger to describe the formation of new beliefs and increased proselytizing in order to reduce the tension, or dissonance, that results from failed prophecies.[46] According to the theory, believers experienced tension following the failure of Jesus's reappearance in 1844, which led to a variety of new explanations. The various solutions form a part of the teachings of the different groups that outlived the disappointment.

See also

[edit]- 2011 end times prediction

- Adventism

- Adventist

- Burned-over district

- Christian revival

- Christianity in the 19th century

- Day-year principle

- Edgar C. Whisenant

- Escalation of commitment

- Harold Camping

- List of Christian denominations § Millerites and comparable groups

- List of prophecies of Joseph Smith

- List of religions and religious denominations § Adventist and related churches

- Millennialism

- Predictions and claims for the Second Coming of Christ

- Rationalization

- True-believer syndrome

- Unfulfilled Christian religious predictions

- Unfulfilled Watch Tower Society predictions

- When Prophecy Fails

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Seventh-day Adventist Church emerged from religious fervor of 19th Century". 4 October 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Apocalypticism Explained – Apocalypse!". Frontline – PBS. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ a b "The Great Disappointment and the Birth of Adventism". Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Adventist Review Online – Great Disappointment Remembered 170 Years On". 23 October 2014. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Daniel 8:14

- ^ Knight 2000, p. 38.

- ^ Miller, William (November 17, 1842), The Midnight Cry (PDF), p. 4

- ^ Knight 2000, pp. 39–42.

- ^ Daniel 7:25

- ^ Knight 2000, pp. 42–44.

- ^ a b Knight 2000, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Ezekiel 4:6

- ^ Numbers 14:34

- ^ 2 Peter 3:7

- ^ Ezra 1:1–4

- ^ Ezra 6:1–12

- ^ Ezra 7

- ^ Nehemiah 2

- ^ Ezra 7:11–26

- ^ William to Joshua V. Himes, February 4, 1844.

- ^ Knight 1993, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Bliss, Sylvester (1853). Memoirs of William Miller. Boston: Joshua V. Himes. p. 256.

- ^ Samuel S. Snow, The Advent Herald, August 21, 1844, 20.

- ^ "The Great Disappointment | Grace Communion International". www.gci.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-23. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

- ^ Knight 1993, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Revelation 6:11

- ^ White, James (1875). Sketches of the Christian Life and Public Labors of William Miller: Gathered From His Memoir by the Late Sylvester Bliss, and From Other Sources. Battle Creek: Steam Press of the Seventh-day Adventist Publishing Association. p. 310.

- ^ Knight 1993, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Mark 10:15

- ^ Revelation 14:14–16

- ^ Cross, Whitney R. (1950). The Burned-over District: A Social and Intellectual History of Enthusiastic Religion in Western New York. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 310.

- ^ Knight 1993, p. 232.

- ^ Matthew 25:1–13

- ^ Dick, Everett N. (1994). William Miller and the Advent Crisis. Berrien Springs, Michigan: Andrews University Press. p. 25.

- ^ Matthew 25:11–12

- ^ Knight 1993, p. 236.

- ^ Knight 1993, p. 305.

- ^ Knight 1993, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Momen, Moojan (1992). "Fundamentalism and Liberalism: towards an understanding of the dichotomy". Baháʼí Studies Review. 2 (1).

- ^ Cameron, G.; Momen, W. (1996). A Basic Bahá'í Chronology. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. pp. 15–20, 125. ISBN 0-85398-404-2.

- ^ Shoghi Effendi Rabbani. God Passes By. p. 9.

- ^ a b Sears, William (1961). Thief in the Night. London: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-008-X.

- ^ Bowers, Kenneth E. (2004). God Speaks Again: An Introduction to the Bahá'í Faith. Baha'i Publishing Trust. p. 12. ISBN 1-931847-12-6.

- ^ Motlagh, Hushidar Hugh (1992). I Shall Come Again (The Great Disappointment ed.). Mt. Pleasant, MI: Global Perspective. pp. 205–213. ISBN 0-937661-01-5.

- ^ O'Leary, Stephen (2000). "When Prophecy Fails and When It Succeeds: Apocalyptic Prediction and Re-Entry into Ordinary Time". In Albert I. Baumgarten (ed.). Apocalyptic Time. Brill Publishers. p. 356. ISBN 90-04-11879-9.

Examining Millerite accounts of the Great Disappointment, it is clear that Festinger's theory of cognitive dissonance is relevant to the experience of this apocalyptic movement.

- ^ James T. Richardson. "Encyclopedia of Religion and Society: Cognitive Dissonance". Hartland Institute. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

Bibliography

[edit]- Knight, George R. (1993). Millennial Fever and the End of the World. Boise, Idaho: Pacific Press. ISBN 978-0816311781.

- Knight, George (2000). A Search for Identity. Review and Herald Pub.

- Rowe, David L. (2008). God's Strange Work: William Miller and the End of the World. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-0380-1.