SM-62 Snark

| SM-62 Snark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Surface-to-surface cruise missile |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1959–61 |

| Used by | United States Air Force |

| Production history | |

| Manufacturer | Northrop Corporation |

| Produced | 1958–61 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 48,150 pounds (21,840 kg) without boosters; 60,000 pounds (27,000 kg) with boosters |

| Length | 67 feet 2 inches (20.47 m) |

| Wingspan | 42 feet 3 inches (12.88 m) |

| Warhead | W39 thermonuclear warhead (explosive yield: 3.8 megatons) |

| Engine | 1 Pratt & Whitney J57 jet engine; and 2 Aerojet solid-propellant rocket boosters J57 turbojet: 10,500 pounds-force (47,000 N) of thrust; booster rockets: 130,000 pounds-force (580,000 N) of thrust |

Operational range | 5,500 nautical miles (10,200 km; 6,300 mi) |

| Flight ceiling | 50,250 feet (15,320 m) |

| Maximum speed | 565 knots (1,046 km/h; 650 mph) |

Guidance system | astro-inertial guidance with design CEP of 8,000 feet (2,400 m). |

Launch platform | mobile launcher |

The Northrop SM-62 Snark is an early-model intercontinental range ground-launched cruise missile that could carry a W39 thermonuclear warhead. The Snark was deployed by the United States Air Force's Strategic Air Command from 1958 through 1961. It represented an important step in weapons technology during the Cold War.[1] The Snark was named by Jack Northrop and took its name from the author Lewis Carroll's character the "snark".[2][3]: 1 The Snark was the only surface-to-surface cruise missile with such a long range that was ever deployed by the U.S. Air Force. Following the deployment of ICBMs, the Snark was rendered obsolete, and it was removed from deployment in 1961.

Design and development

[edit]

Project Mastiff, to create a missile for delivery for an atom bomb began immediately after the existence of the atomic bomb was revealed. Due to protracted security concerns of the Manhattan Project the Army Air Force’s new Project Mastiff was a years long “Fiasco” [4]: 85 Despite the failure of Project Mastiff the Army Air Force started a group of programs intended to create atomic bomb carrying missiles.

During the significant first decade of American strategic missile development the Air Force’s attention was upon developing air-breathing missiles.[5]: 3 Designations for individual programs changed over time and thus they are best known by their MX numbers.[4]: 76 Following the end of WWII the Guided Missile Committee decided that the development of guided missiles should be shifted from the existing ad hoc programs in order to concentrate upon basic research.[4]: 57 Northrop was selected to study two concepts, the sub-sonic MX-775A Snark, and the super-sonic MX775B Boojum.[4]: 76 The defense budget cuts of what was called the Black Christmas of 1946 drastically reduced the number of Army missile programs.[4]: 77 Few of those programs which survived resembled the later missiles which they eventually produced.[4]: 79 In March 1947 the MX-775B Boojum supersonic 5,000 mile range and not the subsonic MX-775A Snark was the only Northrop program.[4]: 79 By March 1948 the MX-775A Snark was the preferred missile while the super-sonic MX-775B Boojum had been reduced in importance to a speculative prospect.[4]: 117 Further intense budgetary pressure in 1949 saw the USAF surface to surface missile program reduced to two programs of which one was the MX-775A Snark. By July 1950 the Snark program was further reduced to development of the guidance subsystem and creation of a guidance test vehicle.[4]: 150 [6] The guidance test missile was the Northrop N-25. Development of the heavy stellar navigation system intended for the N-25 Snark was very difficult and required many hundreds of hours of flight aboard aircraft.[7] Twenty-one flights of the N-25 occurred at Holloman AFB, New Mexico between April 1951 and March 1952.[8]: 85

A new requirement for intercontinental range required a new, larger missile. The resulting Northrop N-69 was originally powered by a J71 engine and in later variants a J57.[8]: 86 While 10 of 25 N-25 missiles were recovered, only 11 of 39 N-69s were recovered.[7]: 194 As the available space for tests of an intercontinental ranged missile did not exist at Holloman, testing was moved to the Atlantic Missile Test Range at Cape Canaveral, Florida.[8]: 86 Test Snarks were recovered to a runway at the Joint Long Range Proving Ground which is still known as the "Skid Strip".[9] Unfortunately facilities at Cape Canaveral were still being constructed at the same time aerodynamic problems with the intended dive by the Snark on the target persisted.[7]: 194

The Snark, which was originally projected to become operational in 1953, suffered a protracted test program which involved significant redesigns.[8]: 89 Development of the N-69 dragged on with many failures which caused wags to jest of the “Snark Infested Waters” off Cape Canaveral.[8]: 92 As the prospective operational date of the Snark slipped continuously into the future, Strategic Air Command (SAC) grew more skeptical of the missile. Criticism of the Snark grew from doubts by SAC in 1951 to serious objections in 1954.[8]: 93 A high-level study by the Teapot Committee in early 1954 described the nascent Atlas ICBM project as beset by technical and administrative problems while advising that the ballistic missile offered the best means of delivering a thermonuclear weapon over intercontinental range.[5]: 37 Also in early 1954 the Strategic Missile Evaluation Committee concluded that the Snark was an “overly complex” and would not become operational until “substantially later” than scheduled.[7]: 195

The failure of the Snark to achieve the necessary accuracy for the original W-8 nuclear weapon (striking within 1,500 feet (460 m) of target) was offset somewhat by the change to the much more powerful W-39-Y1 Mod 1 thermonuclear bomb (striking within 8,000 feet (2,400 m) of target).[8]: 93 [10]: 195 Extensive flight testing, weight reduction efforts, an improved 24 hour stellar navigation system, and the addition of pylon fuel tanks below the wings to restore range capabilities eventually resulted in the N-69E Snark which became the prototype for the SM-62 Intercontinental Missile (ICM)[8]: 95

By late 1957 N-69E Snarks had complete two flights down range to Ascension Island, showing the Snark achieved an estimated circular error probable (CEP) of 17 nautical miles (31 km; 20 mi).[11]: 41 By 1958, the celestial navigation system used by the Snark allowed its most accurate test, which appeared to fall 4 nautical miles (7.4 km) wide of the target.[12] However, even with the decreased CEP, the design was notoriously unreliable, with the majority of tests suffering mechanical failure thousands of miles before reaching the target. Other factors, such as the reduction in operating altitude from 150,000 to 55,000 feet (46,000 to 17,000 m), and the inability of the Snark to detect countermeasures and perform evasive maneuvers also made it a questionable strategic deterrent.[3]: 2 A total of 97 N-25, N69 and SM-62 Snarks tests were made between December 1950 and December 1960.[11]: 42 SAC then changed requirements to require the launch 20% of Snarks within 15 minutes of notification, 40% within 75 minutes, and all in four hours. A daunting requirement given the base design and requirements of the missile.[7]: 198

In late 1957 SAC’s 556 Strategic Missile Squadron launched its first N-69E to begin the Snark Employment and Suitability Test program.[11]: 42 In December 1957 the 556th Strategic Missile Squadron was activated and began training to launch operational SM-62 Snark Missiles. In January 1958, SAC began accepting delivery of Snark missiles at Patrick Air Force Base for training, and in 1959, the 702d Strategic Missile Wing was formed. Snark launches for developmental purposes continued through 1958 but the training activities of the 556th were reduced. Training of Snark missile men at the Cape continued until December 1959.[11]: 43

From December 1950 until December 1960 118 N-25, N-69 and SM-62 test flights were made.[7]: 201–203

Technical description

[edit]

The jet propelled, 67-foot (20.5 m) long Snark missile had a top speed of about 650 miles per hour (1,050 km/h) and a maximum range of about 5,500 nautical miles (10,200 km). Its complicated celestial navigation system gave it a claimed CEP of about 8,000 feet (2,400 m).

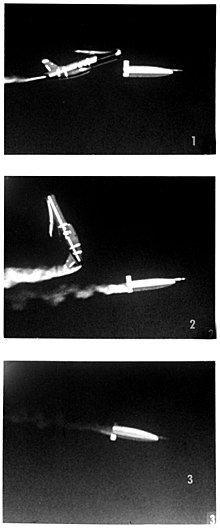

The Snark was an air-breathing missile, intended to be launched from a truck-mounted platform by two solid-fueled rocket booster engines. The Snark was propelled by an internal turbojet engine for the rest of its flight. The engine was a Pratt and Whitney J57, which was the first jet engine featuring a thrust of 10,000 lbf (44,000 N) or more. Since the Snark lacked a horizontal tail surface, it used elevons as its primary flight control surfaces, and it flew with an unusual nose-high angle during level flight. During the final phase of its flight, its nuclear warhead would have separated from its fuselage and then followed a ballistic trajectory towards its target. Due to the sudden shift in its center of gravity caused by separation, the fuselage would have performed an abrupt pitch-up maneuver in order to avoid a collision with the warhead. The resulting break-up of the missiles structure added clutter which confused enemy radar.

Operational history

[edit]

In May 1957, a Detachment of Air Force instructors was formed at Amarillo Air Force Base , Texas as the first cadre of Air Force personnel supporting an Intercontinental missile system. None of the detachment members had any previous training or experience in missile maintenance. They were trained at the Northrop factory in California and then returned to Amarillo to establish the training school for the Snark maintenance personnel.[citation needed]

On January 1, 1959 the 702nd Strategic Missile Wing was activated at Presque Isle, Maine. On 27 May 1959, Presque Isle Air Force Base, Maine, the only Snark missile base, received its first missile. It was ten months before the 702nd placed its first Snark on Alert on March 18, 1960. The first far superior Atlas D had already gone on Alert on October 31, 1957.[13]: 5 Exercises in 1960 indicated that only 20% of the missiles at Presque Isle met SAC standards of effectiveness.[7]: 197 Reliability improved over time with reliability achieving 95% in February 1961.[7]: 197

The 702nd Wing was not declared to be fully operational until February 1961. A total of 30 Snarks were deployed to the USAF's first and only long-range cruise missile base.[14] The duration of the SM-62 in active service was brief before the reality which had haunted the program since the Teapot Committee caught up with it. In March 1961, President John F. Kennedy declared the Snark to be "obsolete and of marginal military value", and on 25 June 1961, the 702nd Wing was inactivated.[15]

Many in the U.S. Military were surprised the Snark, due to its dubious guidance system, was ever operational. The most accurate of the seven full-range flights from June 1958 and May 1959 had fallen 4.2 nautical miles (7,800 m) left of and 0.3 nautical miles (560 m) short the target. In flight tests many were lost. A missile launched from Cape Canaveral in 1956 that was supposed to fly to Puerto Rico and back, flew so far off course that it was last seen on radar off the coast of Venezuela. The wreckage of the wayward Snark missile was found in northeastern Brazil in 1983.[16][17][18] Many of those connected with the program commented in jest "that the Caribbean was full of 'Snark infested waters'."[19] The Snark suffered from deficiencies in missile technology, design, and development which delayed its entry into service until it had been overtaken by development of the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile. The ICBM was capable of delivering the same thermonuclear weapon over the same distance much faster and without possibility of interception.[8]: 103

Surviving missiles

[edit]Five Snark missiles survive in museum collections. They are located as follows:

- Air Force Space & Missile Museum at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station at Cape Canaveral, Florida.[20]

- National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.[21]

- Strategic Air Command & Aerospace Museum in Ashland, Nebraska near Omaha.[22]

- Hill Aerospace Museum at Hill Air Force Base in Ogden, Utah.[23]

- National Museum of Nuclear Science & History near Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque, New Mexico.[24]

See also

[edit]Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Northrop SM-62 Snark. National Museum of the United States Air Force. May 29, 2015.

- ^ Carroll and Gardner 1982, p. 97.

- ^ a b ‘’From Snark to Peacekeeper. Office of the Historian, Strategic Air Command, Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska (1990).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rosenberg, Max (1988). The U.S. Air Force and The National Guided Missile Program 1944-1950. USAF Historical Division Liaison Office, USAF, Washington D.C.

- ^ a b Lonnquest, John C., Winkler, David F. (1996). ‘’To Defend and Deter: the Legacy of the United States Cold War Missile Program‘’. U.S. Army Construction Engineering Research Laboratories, Champaign, Illinois.

- ^ Reed, Irving, The Dawn of the Computer Age, https://calteches.library.caltech.edu/4159/1/Computer.pdf, Engineering and Science, Caltech Magazine

- ^ a b c d e f g h Werrell, Kenneth (1988). ‘’The Case Study of Failure‘’ American Aviation Historical Society Journal, Fall 1988.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Werrell, Kenneth (1985). ‘’The Evolution of the Cruise Missile‘’. Air University Press, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama.

- ^ Snark Lands on Skids With Little Damage, https://archive.aviationweek.com/issue/19580421#!&pid=138, Aviation Week including Space Technology, McGraw-Hill, NY

- ^ Hansen, Chuck (1988). U.S. Nuclear Weapons - The Secret History. Aerofax, Arlington Texas. ISBN 0-517-56740-7

- ^ a b c d Cleary, Mark C. (1990) ‘’The 6555th Missile and Space Launches Through 1970”. 45th Space Wing History Office, Patric AFB, Florida).

- ^ Anderson, Fred (2016). Northrop: An Aeronautical History. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-5326-0356-3.

- ^ ‘’Alert Operations and the Strategic Air Command, 1957-1991”. Office of the Historian, Strategic Air Command, Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska (1991).

- ^ Gibson 1996, p. 151.

- ^ "U.S. Air Force Fact Sheet: Development of the 45SW Eastern Rqnge." Archived 2012-02-06 at the Wayback Machine United States Air Force. Retrieved: 12 April 2012.

- ^ "Snark ignores Air Force 'orders'." Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 8 December 1956. Retrieved: 6 January 2013.

- ^ "Long-lost missile found." The Leader-Post, 15 January 1983. Retrieved: 6 January 2013.

- ^ "The Day They Lost the Snark" Air Force Magazine, December 2004. Retrieved: 17 August 2018.

- ^ Zaloga 1993, p. 193.

- ^ "Snark". Air Force Space & Missile Museum. Air Force Space and Missile Museum. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ "Northrop SM-62 Snark". National Museum of the US Air Force. 29 May 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ "Missiles & Rockets". Strategic Air Command & Aerospace Museum. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ "Northrop XSM-62A Snark". Hill Air Force Base. 16 October 2008. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ "Heritage Park". The National Museum of Nuclear Science & History. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]- ‘’Alert Operations and the Strategic Air Command, 1957-1991”. Office of the Historian, Strategic Air Command, Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska (1991

- Carroll, Lewis and Martin Gardner. Lewis Carroll's The Hunting of the Snark: The Annotated Snark. London: William Kaufmann, 1982. ISBN 978-0-913232-36-1.

- Cleary, Mark C. ‘’The 6555th Missile and Space Launches Through 1970”. 45th Space Wing History Office, Patrick AFB, Florida. 1990

- Gibson, James N. Nuclear Weapons of the United States: An Illustrated History. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 1996. ISBN 0-7643-0063-6.

- Hansen, Chuck. U.S. Nuclear Weapons - The Secret History. Arlington, Texas: Aerofax, 1988. ISBN 0-517-56740-7.

- “From Snark to Peacekeeper”. Office of the Historian, Strategic Air Command, Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska (1990).

- Lonnquest, John C, and Winkler, David F. ‘’To Defend and Deter: the Legacy of the United States Cold War Missile Program’’. Champaign, Illinois: US Army Construction Engineering Research Laboratories/Defense Publishing Service, Rock Island, Illinois 1996.

- Rosenberg, Max. ‘’The U.S. Air Force and The National Guided Missile Program 1944-1950. USAF Historical Division Liaison Office, USAF, Washington D.C. 1988

- Werrel, Kenneth, ‘’The Case Study of Failure‘’. American Aviation Historical Society Journal, Fall 1988

- Werrel, Kenneth, ‘’The Evolution of the Cruise Missile‘’. Air University Press, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama. 1985

- Zaloga, Steven J. "Chapter 5." Target America: The Soviet Union and the Strategic Arms Race, 1945–1964. New York: Presidio Press, 1993. ISBN 0-89141-400-2.

External links

[edit]- The Day They Lost The Snark by J.P. Anderson, Air Force Magazine article about a Snark that was test-fired and rumored to have been found in Brazil

- Snark Lands on Skids With Little Damage

- The Dawn of the Computer Age

- Excellent article on the Snark on FAS.org

- "Our First Guided Missileaires", Popular Mechanics, July 1954, detailed article on Snark and the USAF school to train personnel for it