Jane Arden (director)

Jane Arden | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Norah Patricia Morris 29 October 1927[citation needed] Pontypool, Monmouthshire, Wales |

| Died | 20 December 1982 (aged 55) |

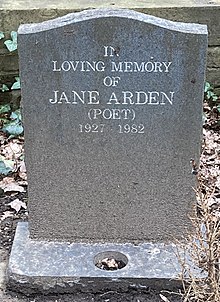

| Resting place | Highgate Cemetery (west side) |

| Alma mater | Royal Academy of Dramatic Art |

| Occupation(s) | Actress, film director, playwright, poet, screenwriter and songwriter |

| Spouse | Philip Saville |

| Children | 2 |

Jane Arden (born Norah Patricia Morris; 29 October 1927 – 20 December 1982) was a British film director, actress, singer/songwriter and poet, who gained note in the 1950s. Born in Pontypool, Monmouthshire, she studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. She started acting in the late 1940s and writing for stage and television in the 1950s. In the 1960s, she joined movements for feminism and anti-psychiatry. She wrote a screenplay for the film Separation (1967). In the late 1960s and 1970s, she wrote for experimental theatre, adapting one work as a self-directed film, The Other Side of the Underneath (1972). In 1978 she published a poetry book. Arden committed suicide in 1982. In 2009, her feature films Separation (1967), The Other Side of the Underneath (1972) and Anti-Clock (1979) were restored by the British Film Institute and released on DVD and Blu-ray. Her literary works are out of print.

Early life

[edit]Arden was born Norah Patricia Morris at 47 Twmpath Road, Pontypool, Monmouthshire, Wales.[1]

Career

[edit]Arden studied acting at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London and began a career in the late 1940s on television and in film.[2] She appeared in a television production of Romeo and Juliet in the late 1940s and starred in two British crime films: Black Memory (1947) directed by Oswald Mitchell – which provided South African-born actor Sid James with his first screen credit (billed as Sydney James) – and Richard M. Grey's A Gunman Has Escaped (1948). In 2017 Renown Pictures released both films on DVD in a set of three discs, Crime Collection Volume One.

Writing and theatre

[edit]In the 1950s Arden married the director Philip Saville. After a short spell in New York, where she began writing, the couple settled in Hampstead and had two sons. Arden then wrote several plays and television scripts, some of which her husband directed.[3]

Arden worked in the late 1950s with some leading figures in British theatre and cinema. Her stage play Conscience and Desire, and Dear Liz (1954) gained interest. Her comic television drama Curtains For Harry (1955) starring Bobby Howes and Sydney Tafler was shown on 20 October 1955 by the new ITV network,[4] featuring also the Carry On actress Joan Sims. Arden's co-writer on this was the American Richard Lester, who was working as a television director at the time.

In 1958, her play The Party, a family drama set in Kilburn, was directed at London's New Theatre by Charles Laughton.[5] It turned out to be Laughton's last appearance on the London stage, while providing Albert Finney with his first.[3] Her television drama The Thug (1959) gave Alan Bates a powerful early role.[6] In 1964, Arden appeared with Harold Pinter in In Camera, a television production of Jean-Paul Sartre's Huis Clos directed by Saville.[7]

Feminism, film and radical theatre

[edit]Arden's work became increasingly radical through her growing involvement in feminism and the anti-psychiatry movement of the 1960s. This is particularly clear from 1965 onwards, starting with the television drama The Logic Game, which she wrote and starred in.[3] The Logic Game, directed by Saville, also starred the British actor David de Keyser, who worked with her again in the film Separation (1967).[8] Arden wrote the screenplay; the film was directed by Jack Bond. Separation, shot in black and white by Aubrey Dewar, featured music by the group Procol Harum.[9]

Arden and Bond had hitherto worked on the documentary film Dalí in New York (1966), which has the surrealist Salvador Dalí and Arden walking the streets of New York City and discussing Dalí's work.[10] This was resurrected and shown at the 2007 Tate Gallery Dalí exhibition.[11]

Arden's television work in the mid-1960s included appearances in Saville's Exit 19, Jack Russell's The Interior Decorator, and the satirical programme That Was the Week That Was hosted by David Frost.[12] Her work in experimental theatre in the late 1960s and the 1970s coincided with a return to cinema as an actor, writer and director or co-director.[3]

The play Vagina Rex and the Gas Oven (1969), starring Victor Spinetti, and Sheila Allen, was sold out for six weeks at London's Arts Lab.[13] It was described by Arthur Marwick as "perhaps the most important single production" at the venue during that period.[14] Also around that time Arden wrote the drama The Illusionist.

In 1970, Arden formed the radical feminist theatre group Holocaust and wrote the play A New Communion for Freaks, Prophets and Witches, which would later be adapted for the screen as The Other Side of the Underneath (1972).[15] She directed the film and appeared in it uncredited; screenings at film festivals, including the 1972 London Film Festival, caused a major stir. It depicts a woman's mental breakdown and rebirth in scenes at times violent and shocking; the writer and critic George Melly called it "a most illuminating season in Hell",[16] while the BBC Radio journalist David Will called it "a major breakthrough for the British cinema".[17]

Throughout her life, Arden's interest in other cultures and belief systems increasingly took the form of a personal spiritual quest.[citation needed]

After The Other Side of the Underneath came two further collaborations with Jack Bond in the 1970s: Vibration (1974), described by Geoff Brown and Robert Murphy in their book Film Directors in Britain and Ireland (British Film Institute 2006) as "an exercise in meditation utilising experimental film and video techniques",[18] and the futuristic Anti-Clock (1979), which featured Arden's songs and starred her son Sebastian Saville. The latter opened the 1979 London Film Festival.[citation needed]

In 1978, Arden published the book You Don't Know What You Want, Do You? and supported its publication with public readings and discussions, for instance at the King's Head Theatre in London on 1 October 1978. Although loosely defined as poetry, it is also a radical socio-psychological manifesto comparable to R. D. Laing's Knots. By this time, Arden had moved on from feminism to a view that all people needed freeing from the tyranny of rationality.[citation needed]

Personal life

[edit]Jane Arden had two sons with Philip Saville: Sebastian and Dominic.[19]

Death

[edit]Arden had been depressed in the last years of her life. She committed suicide at Hindlethwaite Hall in Coverdale, Yorkshire, on 20 December 1982.[citation needed] Her death had an effect on Bond, who elected to store the films he made with Arden in a National Film Archive laboratory without release for several years.[20][21]

Legacy

[edit]In July 2008, Arden was among the topics discussed at the Conference of 1970s British Culture and Society held at the University of Portsmouth.[citation needed]

In 2009, the British Film Institute restored the three major feature films Arden made with her creative associate Jack Bond: Separation (1967), The Other Side of the Underneath (1972) and Anti-Clock (1979).[22][23][24] These became available on DVD and Blu-ray in July 2009.[25] Bond was involved in the restoration and reissue processes; the releases were accompanied by an exhibition of the restored features at the National Film Theatre and The Cube Microplex in Bristol.[26] Her books – poetry and plays – remain out of print.[citation needed]

As a tribute to Arden, the experimental-music group Hwyl Nofio, fronted by Steve Parry from Pontypool, included the song "Anti-Clock" on their album Dark (2012).[27]

Selected works

[edit]Feature films

[edit]Director

[edit]- Separation (1968 - writer, actor)

- The Other Side of the Underneath (1972 - writer, actor, director)

- Anti-Clock (1979 - writer, composer, co-director)

Actor

[edit]- Black Memory (1947 - actor)

- A Gunman Has Escaped (1948 - actor)

Short films

[edit]- Vibration (1975 - writer, co-director, cinematography, editing)

Television

[edit]- Romeo and Juliet (1947 - BBC Television, actor)

- Curtains For Harry (1955 - ITV, co-writer)

- The Thug (1959 - ITV, writer)

- Huis Clos (1964 - BBC Television, actor)

- The Logic Game (1965 - BBC Television, writer, actor)

- The Interior Decorator (1965 - television play, actor)

- Exit 19 (1966 - television play, a commentator)

- Dalí in New York (1966 - BBC Television, interviewer)

Bibliography

[edit]- Conscience and Desire, and Dear Liz (1954 - theatre, playwright)

- The Party (1958 - theatre, playwright)

- The Illusionist (1968 - writer)

- Vagina Rex and the Gas Oven (1969 - theatre, writer)

- A New Communion for Freaks, Prophets and Witches (1971, theatre, playwright)

- You Don't Know What You Want, Do You? (1978 - poetry, writer)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jane Arden at babylonwales.blogspot.com.

- ^ Fabrique. "Jane Arden – RADA". Rada.ac.uk.

- ^ a b c d "Arden, Jane (1927-82)". Screen Online.

- ^ "Curtains for Harry (1955)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 30 December 2018.

- ^ "Obituary: Albert Finney". BBC News. 8 February 2019.

- ^ "The Thug (1959)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020.

- ^ "In Camera (1964)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Separation (1968)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016.

- ^ "Ian Hockley reviews 'Separation' in London on Bastille Day 2009". Procolharum.com.

- ^ "Dali in New York (1966)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020.

- ^ "VERTIGO – Arden and Dali Loiter in the Streets". Closeupfilmcentre.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ "Jane Arden". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Vagina Rex and the Gas Oven (1/2)".

- ^ Marwick, Arthur (1998). The Sixties. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 352. ISBN 0-19-288100-0.

- ^ "The Other Side of the Underneath (1973)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021.

- ^ Vertigo Magazine: Unknown pleasures: By Sean Kaye-Smith. Retrieved August 2007.

- ^ "VERTIGO – Unknown Pleasures". Closeupfilmcentre.com.

- ^ Horizon Information Portal: Summary.

- ^ Hadoke, Toby (1 January 2017). "Philip Saville obituary". The Guardian.

- ^ "Muriel Zagha on the rerelease of Anti-Clock". The Guardian. 9 July 2009.

- ^ "Jack Bond". 2 September 2009.

- ^ "Separation". British Film Institute.

- ^ "The Other Side of the Underneath". British Film Institute.

- ^ "Anti-Clock". British Film Institute.

- ^ "The Films of Jane Arden & Jack Bond". Mondo-digital.com.

- ^ "Cube: Bfi Jane Arden And Jack Bond Season: Separation". Cubecinema.com.

- ^ "Hwyl Nofio – Dark". Discogs. January 2013.

Sources

[edit]- Film Directors in Britain and Ireland (BFI 2006) edited by Robert Murphy

- Unknown Pleasures: Vertigo Magazine online August 2007 [1]

- Arden and Dalí Loiter in the Streets: Vertigo Magazine online [2]

- Jane Arden, Jethro Tull and 1973: Vertigo Magazine online August 2008 [3]

External links

[edit]- Jane Arden at IMDb

- Jane Arden at the BFI's Screenonline

- 1927 births

- 1982 deaths

- 1982 suicides

- 20th-century Welsh composers

- 20th-century Welsh dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century Welsh screenwriters

- 20th-century Welsh women musicians

- 20th-century Welsh actresses

- 20th-century Welsh poets

- 20th-century Welsh women writers

- 20th-century British women composers

- Actresses from London

- Alumni of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art

- Welsh women dramatists and playwrights

- Burials at Highgate Cemetery

- Film directors from London

- Composers from London

- People from Pontypool

- Suicides in England

- British expatriate actresses in the United States

- Welsh feminists

- Welsh film actresses

- Welsh television actresses

- Welsh women songwriters

- Welsh women film directors

- Welsh women poets

- British women television writers

- Writers from London

- Feminist musicians

- Anti-psychiatry

- 20th-century English women

- 20th-century English poets