Hainan black crested gibbon

| Hainan gibbon[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| N. n. hainanus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hylobatidae |

| Genus: | Nomascus |

| Species: | N. hainanus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Nomascus hainanus (Thomas, 1892)

| |

| |

| Hainan gibbon range | |

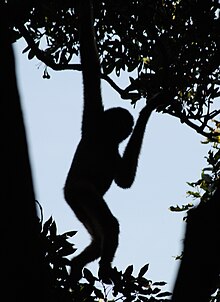

The Hainan black-crested gibbon (Nomascus hainanus), also called the Hainan gibbon, is a Critically Endangered species of gibbon found only on Hainan Island, in the Pacific Ocean.

It was formerly considered a subspecies of the eastern black crested gibbon (N. nasutus) from Hòa Bình and Cao Bằng provinces of Vietnam and Jingxi County in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China. Molecular data, together with morphology and call differences, suggest it is a separate species.[4] Its habitat consists of broad-leaved forests and semi-deciduous monsoon forests.[5] It feeds on ripe, sugar-rich fruit, such as figs and, at times, leaves, and insects.[5]

Current status

[edit]Hainan black-crested gibbons are under grave threat of extinction. They are currently identified as critically endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List.[2] Historically, they were widespread in China: Government records dating back to the 17th century state that their range used to cover half of China,[6] although the records in question might represent multiple species, as some are from areas separated from each other by physical barriers such as large rivers that gibbons would have difficulty crossing.[7] The gibbon population on Hainan Island has decreased precipitously over the last half century. While in the 1950s, more than 2,000 gibbons were found over the entirety of Hainan Island, a study in 2003 found 13 total gibbons split into two groups and two lone males,[8] and in 2004 only 12–19 Hainan gibbons were found exclusively in the Hainan Bawangling National Nature Reserve.[9] The most recent count found 22 Hainan gibbons split between two families, one of 11 and one of seven members, with four loners, all residing in Bawangling National Nature Reserve on Hainan Island. Habitat loss is the primary cause in the decline of the Hainan gibbon; poaching has also been a problem.[10] Over 25% of the Hainan gibbon’s habitat has been reduced due to illegal pulp paper plantation growers.[11] Originally denizens of lowland forest, logging has driven them to less suitable habitat at higher altitudes.[10] The species is currently vulnerable to being eliminated by a single major storm or epidemic.[10]

Physical and breeding characteristics

[edit]Sexual dichromatism is distinct in the Hainan gibbon.[5] The males are all almost completely black, with sometimes white or buff cheeks. Females, conversely, are a golden or buff color with black patches, including a streak of black on the head.[5] Both males and females are slender, with long arms and legs and no tail.[5] The arms are used to swing from tree to tree, which is known as brachiation. The Hainan gibbon sings duets for bonding and mating.[5]

The Hainan gibbons have acquired some reproductive adaptations in response to their drastically decreased natural habitat. The few remaining gibbons exhibit polygynous relationships; small families typically consist of one breeding male, two mature females, and their offspring. This stable pair bond relationship seems to have allowed the gibbons to decrease their interbirth interval, the length of time between births.[12] Their two-year interbirth interval is shorter than that of most gibbon species and coincides with the blooming patterns of fruits on the Hainan Islands.[12] The Hainan gibbon also has a shorter gestation period than other gibbon species. It has been observed that not all sexually mature females in the wild are breeding, however, the reasons for this are unclear.[12]

Habitat selection

[edit]The Hainan gibbons reside in three different types of forests on the island. Their main area of occupancy is known as the primary forest (Old-growth forest). Within the primary forest the gibbons typically live in trees that are ten meters or taller.[13] Along with offering sources of shelter and trees for singing rituals, the primary forests are also home to at least six species of plants eaten by the gibbons.[13] When primary forests are destroyed, it takes the trees an extensive amount of time to regenerate to a state that is suitable as a home for the gibbons. In the 1960s, much of Hainan's lowlands were deforested to make way for rubber plantations and commercial logging, causing a dramatic decline in their population. These actions forced gibbon communities to higher elevations. By 1999, only 4% of the gibbons’ original habitat remained on the island.[13]

Aside from primary forest, the gibbons split their time between two areas known as secondary forests and dwarf forests.[13] The secondary forests are less suitable for the Hainan gibbons than the primary forests. Their trees are shorter in height, and they severely lack resources, such as food and shelter, needed by the gibbons to survive. The dwarf forest is even less favorable for the gibbons and a study by Fan et al. found that gibbons spent only 0.5% of the 13-month study period in dwarf forests. Nonetheless, the dwarf forests still account for a small portion of their habitat and are used by gibbons to move between primary forests.[13] Even with the secondary and dwarf forests for the gibbons to reside in, the destruction of primary forests still severely impacts the gibbon population in a negative manner.

Resource availability, predation, and human expansion

[edit]A major result of habitat loss is the reduction of resources available to the Hainan gibbons. While lowland tropical forests are the most suitable habitat for the Hainan gibbon, much of this habitat and approximately 95% of the original vegetation on Hainan Island has been destroyed due to deforestation.[14][15] This natural vegetation has been succeeded by pine and fir trees, which decrease the amount of food available for the gibbons.[14]

Zhou et al. observed two unsuccessful hawk attacks on young gibbons, however, humans are the main threat to the Hainan gibbon. The human population on Hainan exploded 330% between 1950 and 2003, much of which was due to the open door policy implemented by the Chinese government in the late 1980s.[14] Naturally, the population boom led to the construction of roads and towns to accompany the developing rubber and timber industry. Many of these projects led not only to the destruction of habitat where the gibbons were found, but also caused gibbon populations to split and become isolated from other groups of gibbons.[14]

In addition to the economic development brought by the growing population, there is financial pressure to capture gibbons, since a female gibbon can be worth up to 300 US dollars.[14] Gibbon bones are prized in traditional medicine and this belief led to many mass hunts between 1960 and 1980, leading to the death of approximately 100 gibbons.[14] Aside from direct interactions between humans and gibbons, the low income of most residents of Hainan has led to their reliance on the forests for firewood, food, and herbs for use in traditional medicine, further amplifying human impact on the environment.[14]

Ecological significance

[edit]The Hainan gibbon is considered an umbrella species for the Hainan Island.[16] This designation indicates that status of the Hainan gibbon is a marker for the health and stability of its ecosystem. Alterations in the characteristics of the Hainan ecosystem that negatively affect the gibbons are indicative of negative impact on other species as well.

Other species of gibbons have been shown to be important factors in seed dispersal of several plant species, most notably figs and other fruit bearing plants.[17] Therefore, the destruction of the natural vegetation on Hainan Island, coupled with the dwindling gibbon population bodes ill for the recovery of native plant species. This being said, no gibbon species has gone extinct in the modern world and no other primate species has gone extinct since the 1700s.[18] The impact that the extinction of the Hainan gibbon could have is not well characterized due to the limited amount of research on its ecological importance.

Conservation

[edit]Reproduction limitations

[edit]The breeding characteristics for the Hainan gibbon do not lend themselves to rapid population growth. The breeding females have a single offspring every two years and the newborn has a dependence period of roughly a year and a half.[12] Furthermore, there are currently no Hainan gibbons in captivity and all previous attempts to breed them in captivity have failed.[2]

Conservation action plan

[edit]In response to the declining population of Hainan gibbons, a collaborative status survey and conservation plan was published in 2003 and updated in 2005. The survey was backed by members of the Hainanese and mainland Chinese governments, Kadoorie Conservation China, Fauna and Flora International (FFI), and other international institutions. The goals of the survey were to investigate the current status of the Hainan gibbon to better understand its situation and make recommendations.[8] With the initial survey results, the 2005 update focused on reparative action. The recommendations for action focused on several factors, the first being the mitigation of habitat loss by increasing and better equipping patrols of the island to dissuade illegal loggers.[8] Other suggestions included reverting lowland plantations and farms back into habitable forests for gibbons by specifically planting plant species they require for survival, such as figs and myrtle.[8][14] The plan also called for educating the residents of the island on the importance of the Hainan gibbon.

The loss of habitat directly impacts both sources of food and shelter the gibbons need to survive. Greenpeace and FFI conservation groups have been involved in raising public awareness both locally in East Asia and abroad. Currently the Action Plan is underfunded and poorly supported by its participating members, with limited coordination between them. Greenpeace has been calling on Hainan to better enforce its laws on poaching and logging.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Primates". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 180–181. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c Geissmann, T.; Bleisch, W. (2020). "Nomascus hainanus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T41643A17969392. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T41643A17969392.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ Roos, C.; Thanh, V. N.; Walter, L.; Nadler, T. (2007). "Molecular systematics of Indochinese primates" (PDF). Vietnamese Journal of Primatology. 1: 41–53.

- ^ a b c d e f "Black-crested gibbon (Nomascus concolor)". ARKive. Archived from the original on 2009-04-14. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ^ "Hainan gibbon decline charted in Chinese records". BBC News. August 5, 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-05.

- ^ Smith, Kiona (22 June 2018). ""Extinct gibbon in ancient Chinese tomb hints at other lost primate species"". Ars Technica.

- ^ a b c d Geissmann, T.; Chan, B. (2004). "The Hainan black crested gibbon: Most critically endangered ape". Folia Primatologica. 75 (Supplement 1): 116.

- ^ Wu, W.; Wang, X. M.; Claro, F.; Ding, Y.; Souris, A.-C.; Wang, Chundong; Wang, Changhe; Berzins, R. (2004). "The current status of the Hainan black-crested gibbon Nomascus sp. cf. nastutus hainanus in Bawangling National Nature Reserve, Hainan, China". Oryx. 38 (4): 452–456. doi:10.1017/S0030605304000845.

- ^ a b c Cressey, D. (2014-04-08). "Time running out for rarest primate". Nature News. 508 (163): 163. Bibcode:2014Natur.508..163C. doi:10.1038/508163a. PMID 24717492.

- ^ Platt, John R. (2011-12-03). "Illegal Deforestation Threatens the Last 23 Hainan Gibbons". Scientific American.

- ^ a b c d Zhou, J.; F. Wei, M.; Lok, C. B. P.; Wang, D.; Wang, Deli (2008). "Reproductive characters and mating behaviour of wild Nomascus hainanus". International Journal of Primatology. 29 (4): 1037–1046. doi:10.1007/s10764-008-9272-7. S2CID 35519035.

- ^ a b c d e Fan, P. F.; Jiang, X. L.; Tian, C. C. (2009). "The Critically Endangered black crested gibbon Nomascus concolor on Wuliang Mountain, Yunnan, China: the role of forest types in the species' conservation". Oryx. 43 (2): 203–208. doi:10.1017/S0030605308001907 (inactive 1 November 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Zhou, J.; Wei, F.; Li, M.; Zhang, J. F.; Wang, D.; Pan, R. L. (2005). "Hainan black-crested gibbon is headed for extinction". International Journal of Primatology. 26 (2): 453–465. doi:10.1007/s10764-005-2933-x. S2CID 41663138.

- ^ Chan, B. P. L.; Fellowes, J. R.; Geissmann, T.; Zhang, J. F. (2005). "Hainan Gibbon Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan, Version 1" (PDF).

- ^ Zhang, M.; Fellowes, J. R.; Jiang, X.; Wang, W.; Chan, B. P. L.; Ren, G.; Zhu, J. (June 2010). "Degradation of tropical forest in Hainan, China, 1991–2008: Conservation implications for Hainan Gibbon (Nomascus hainanus)". Biological Conservation. 143 (6): 1394–1404. Bibcode:2010BCons.143.1397Z. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2010.03.014.

- ^ McConkey, K. R. (2005). "The Influence of Gibbon Primary Seed Shadows on Post-dispersal Seed Fate in a Lowland Dipterocarp Forest in Central Borneo". Journal of Tropical Ecology. 21 (3): 255–262. doi:10.1017/s0266467405002257. JSTOR 4092030. S2CID 85893629.

- ^ MacPhee, R. (2021). "Xenothrix mcgregori". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T136515A17976302. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T136515A17976302.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.