Noël Coward

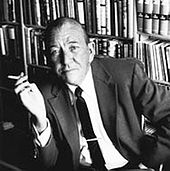

Sir Noël Peirce Coward (16 December 1899 – 26 March 1973) was an English playwright, composer, director, actor, and singer, known for his wit, flamboyance, and what Time magazine called "a sense of personal style, a combination of cheek and chic, pose and poise".[1]

Coward attended a dance academy in London as a child, making his professional stage début at the age of eleven. As a teenager he was introduced into the high society in which most of his plays would be set. Coward achieved enduring success as a playwright, publishing more than 50 plays from his teens onwards. Many of his works, such as Hay Fever, Private Lives, Design for Living, Present Laughter, and Blithe Spirit, have remained in the regular theatre repertoire. He composed hundreds of songs, in addition to well over a dozen musical theatre works (including the operetta Bitter Sweet and comic revues), screenplays, poetry, several volumes of short stories, the novel Pomp and Circumstance, and a three-volume autobiography. Coward's stage and film acting and directing career spanned six decades, during which he starred in many of his own works, as well as those of others.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Coward volunteered for war work, running the British propaganda office in Paris. He also worked with the Secret Service, seeking to use his influence to persuade the American public and government to help Britain. Coward won an Academy Honorary Award in 1943 for his naval film drama In Which We Serve and was knighted in 1970. In the 1950s he achieved fresh success as a cabaret performer, performing his own songs, such as "Mad Dogs and Englishmen", "London Pride", and "I Went to a Marvellous Party".

Coward's plays and songs achieved new popularity in the 1960s and 1970s, and his work and style continue to influence popular culture. He did not publicly acknowledge his homosexuality, but it was discussed candidly after his death by biographers including Graham Payn, his long-time partner, and in Coward's diaries and letters, published posthumously. The former Albery Theatre (originally the New Theatre) in London was renamed the Noël Coward Theatre in his honour in 2006.

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]Coward was born in 1899 in Teddington, Middlesex, a south-western suburb of London. His parents were Arthur Sabin Coward (1856–1937), a piano salesman, and Violet Agnes Coward (1863–1954), daughter of Henry Gordon Veitch, a captain and surveyor in the Royal Navy.[2][n 1] Noël Coward was the second of their three sons, the eldest of whom had died in 1898 at the age of six.[4] Coward's father lacked ambition and industry, and family finances were often poor.[5] Coward was bitten by the performing bug early and appeared in amateur concerts by the age of seven. He attended the Chapel Royal Choir School as a young child. He had little formal schooling but was a voracious reader.[6]

Encouraged by his ambitious mother, who sent him to a dance academy in London,[7] Coward's first professional engagement was in January 1911 as Prince Mussel in the children's play The Goldfish.[8] In Present Indicative, his first volume of memoirs, Coward wrote:

One day ... a little advertisement appeared in the Daily Mirror.... It stated that a talented boy of attractive appearance was required by a Miss Lila Field to appear in her production of an all-children fairy play: The Goldfish. This seemed to dispose of all argument. I was a talented boy, God knows, and, when washed and smarmed down a bit, passably attractive. There appeared to be no earthly reason why Miss Lila Field shouldn't jump at me, and we both believed that she would be a fool indeed to miss such a magnificent opportunity.[9]

The leading actor-manager Charles Hawtrey, whom the young Coward idolised and from whom he learned a great deal about the theatre, cast him in the children's play Where the Rainbow Ends. Coward played in the piece in 1911 and 1912 at the Garrick Theatre in London's West End.[10][11] In 1912 Coward also appeared at the Savoy Theatre in An Autumn Idyll (as a dancer in the ballet) and at the London Coliseum in A Little Fowl Play, by Harold Owen, in which Hawtrey starred.[12] Italia Conti engaged Coward to appear at the Liverpool Repertory Theatre in 1913, and in the same year he was cast as the Lost Boy Slightly in Peter Pan.[13] He reappeared in Peter Pan the following year, and in 1915 he was again in Where the Rainbow Ends.[14] He worked with other child actors in this period, including Hermione Gingold (whose mother threatened to turn "that naughty boy" out);[15] Fabia Drake; Esmé Wynne, with whom he collaborated on his earliest plays; Alfred Willmore, later known as Micheál Mac Liammóir; and Gertrude Lawrence who, Coward wrote in his memoirs, "gave me an orange and told me a few mildly dirty stories, and I loved her from then onwards."[11][16][17]

In 1914, when Coward was fourteen, he became the protégé and probably the lover of Philip Streatfeild, a society painter.[18] Streatfeild introduced him to Mrs Astley Cooper and her high society friends.[n 2] Streatfeild died from tuberculosis in 1915, but Mrs Astley Cooper continued to encourage her late friend's protégé, who remained a frequent guest at her estate, Hambleton Hall in Rutland.[20]

Coward continued to perform during most of the First World War, appearing at the Prince of Wales Theatre in 1916 in The Happy Family[17] and on tour with Amy Brandon Thomas's company in Charley's Aunt. In 1917, he appeared in The Saving Grace, a comedy produced by Hawtrey. Coward recalled in his memoirs, "My part was reasonably large and I was really quite good in it, owing to the kindness and care of Hawtrey's direction. He took endless trouble with me ... and taught me during those two short weeks many technical points of comedy acting which I use to this day."[21]

In 1918, Coward was conscripted into the Artists Rifles but was assessed as unfit for active service because of a tubercular tendency, and he was discharged on health grounds after nine months.[22] That year he appeared in the D. W. Griffith film Hearts of the World in an uncredited role. He began writing plays, collaborating on the first two (Ida Collaborates (1917) and Women and Whisky (1918)) with his friend Esmé Wynne.[23] His first solo effort as a playwright was The Rat Trap (1918) which was eventually produced at the Everyman Theatre, Hampstead, in October 1926.[24] During these years, he met Lorn McNaughtan,[n 3] who became his private secretary and served in that capacity for more than forty years, until her death.[26]

Inter-war successes

[edit]In 1920, at the age of 20, Coward starred in his own play, the light comedy I'll Leave It to You. After a three-week run in Manchester it opened in London at the New Theatre (renamed the Noël Coward Theatre in 2006), his first full-length play in the West End.[27] Neville Cardus's praise in The Manchester Guardian was grudging.[28] Notices for the London production were mixed, but encouraging.[29] The Observer commented, "Mr Coward... has a sense of comedy, and if he can overcome a tendency to smartness, he will probably produce a good play one of these days."[30] The Times, on the other hand, was enthusiastic: "It is a remarkable piece of work from so young a head – spontaneous, light, and always 'brainy'."[31]

The play ran for a month (and was Coward's first play seen in America),[27] after which Coward returned to acting in works by other writers, starring as Ralph in The Knight of the Burning Pestle in Birmingham and then London.[32] He did not enjoy the role, finding Francis Beaumont and his sometime collaborator John Fletcher "two of the dullest Elizabethan writers ever known ... I had a very, very long part, but I was very, very bad at it".[33] Nevertheless, The Manchester Guardian thought that Coward got the best out of the role,[34] and The Times called the play "the jolliest thing in London".[35]

Coward completed a one-act satire, The Better Half, about a man's relationship with two women. It had a short run at The Little Theatre, London, in 1922. The critic St John Ervine wrote of the piece, "When Mr Coward has learned that tea-table chitter-chatter had better remain the prerogative of women he will write more interesting plays than he now seems likely to write."[36] The play was thought to be lost until a typescript was found in 2007 in the archive of the Lord Chamberlain's Office, the official censor of stage plays in the UK until 1968.[37]

In 1921, Coward made his first trip to America, hoping to interest producers there in his plays. Although he had little luck, he found the Broadway theatre stimulating.[38] He absorbed its smartness and pace into his own work, which brought him his first real success as a playwright with The Young Idea. The play opened in London in 1923, after a provincial tour, with Coward in one of the leading roles.[39] The reviews were good: "Mr Noël Coward calls his brilliant little farce a 'comedy of youth', and so it is. And youth pervaded the Savoy last night, applauding everything so boisterously that you felt, not without exhilaration, that you were in the midst of a 'rag'."[40] One critic, who noted the influence of Bernard Shaw on Coward's writing, thought more highly of the play than of Coward's newly found fans: "I was unfortunately wedged in the centre of a group of his more exuberant friends who greeted each of his sallies with 'That's a Noëlism!'"[41][n 4] The play ran in London from 1 February to 24 March 1923, after which Coward turned to revue, co-writing and performing in André Charlot's London Calling![43]

In 1924, Coward achieved his first great critical and financial success as a playwright with The Vortex. The story is about a nymphomaniac socialite and her cocaine-addicted son (played by Coward). Some saw the drugs as a mask for homosexuality;[44] Kenneth Tynan later described it as "a jeremiad against narcotics with dialogue that sounds today not so much stilted as high-heeled".[45] The Vortex was considered shocking in its day for its depiction of sexual vanity and drug abuse among the upper classes. Its notoriety and fiery performances attracted large audiences, justifying a move from a small suburban theatre to a larger one in the West End.[46] Coward, still having trouble finding producers, raised the money to produce the play himself. During the run of The Vortex, Coward met Jack Wilson, an American stockbroker (later a director and producer), who became his business manager and lover. At first Wilson managed Coward's business affairs well, but later abused his position to embezzle from his employer.[47]

The success of The Vortex in both London and America caused a great demand for new Coward plays. In 1925 he premiered Fallen Angels, a three-act comedy that amused and shocked audiences with the spectacle of two middle-aged women slowly getting drunk while awaiting the arrival of their mutual lover.[48] Hay Fever, the first of Coward's plays to gain an enduring place in the mainstream theatrical repertoire, also appeared in 1925. It is a comedy about four egocentric members of an artistic family who casually invite acquaintances to their country house for the weekend and bemuse and enrage each other's guests. Some writers have seen elements of Coward's old mentor, Mrs Astley Cooper, and her set in the characters of the family.[49] By the 1970s the play was recognised as a classic, described in The Times as a "dazzling achievement; like The Importance of Being Earnest, it is pure comedy with no mission but to delight, and it depends purely on the interplay of characters, not on elaborate comic machinery."[50] By June 1925 Coward had four shows running in the West End: The Vortex, Fallen Angels, Hay Fever and On with the Dance.[51] Coward was turning out numerous plays and acting in his own works and others'. Soon his frantic pace caught up with him while starring in The Constant Nymph. He collapsed and was ordered to rest for a month; he ignored the doctors and sailed for the US to start rehearsals for his play This Was a Man.[52] In New York he collapsed again, and had to take an extended rest, recuperating in Hawaii.[53]

Other Coward works produced in the mid-to-late 1920s included the plays Easy Virtue (1926), a drama about a divorcée's clash with her snobbish in-laws; The Queen Was in the Parlour, a Ruritanian romance; This Was a Man (1926), a comedy about adulterous aristocrats; The Marquise (1927), an eighteenth-century costume drama; Home Chat (1927), a comedy about a married woman's fidelity; and the revues On with the Dance (1925) and This Year of Grace (1928). None of these shows has entered the regular repertoire, but the last introduced one of Coward's best-known songs, "A Room with a View".[54] His biggest failure in this period was the play Sirocco (1927), which concerns free love among the wealthy. It starred Ivor Novello, of whom Coward said, "the two most beautiful things in the world are Ivor's profile and my mind".[55] Theatregoers hated the play, showing violent disapproval at the curtain calls and spitting at Coward as he left the theatre.[56] Coward later said of this flop, "My first instinct was to leave England immediately, but this seemed too craven a move, and also too gratifying to my enemies, whose numbers had by then swollen in our minds to practically the entire population of the British Isles."[57]

By 1929 Coward was one of the world's highest-earning writers, with an annual income of £50,000, more than £3 million in terms of 2020 values.[58] Coward thrived during the Great Depression, writing a succession of popular hits.[59] They ranged from large-scale spectaculars to intimate comedies. Examples of the former were the operetta Bitter Sweet (1929), about a woman who elopes with her music teacher,[60] and the historical extravaganza Cavalcade (1931) at Drury Lane, about thirty years in the lives of two families, which required a huge cast, gargantuan sets and a complex hydraulic stage. Its 1933 film adaptation won the Academy Award for best picture.[61] Coward's intimate-scale hits of the period included Private Lives (1930) and Design for Living (1932). In Private Lives, Coward starred alongside his most famous stage partner, Gertrude Lawrence, together with the young Laurence Olivier. It was a highlight of both Coward's and Lawrence's career, selling out in both London and New York. Coward disliked long runs, and after this he made a rule of starring in a play for no more than three months at any venue.[62] Design for Living, written for Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, was so risqué, with its theme of bisexuality and a ménage à trois, that Coward premiered it in New York, knowing that it would not survive the censor in London.[63]

In 1933 Coward wrote, directed and co-starred with the French singer Yvonne Printemps in both London and New York productions of an operetta, Conversation Piece (1933).[64] He next wrote, directed and co-starred with Lawrence in Tonight at 8.30 (1936), a cycle of ten short plays, presented in various permutations across three evenings.[n 5] One of these plays, Still Life, was expanded into the 1945 David Lean film Brief Encounter.[66] Tonight at 8.30 was followed by a musical, Operette (1938), from which the most famous number is "The Stately Homes of England", and a revue entitled Set to Music (1938, a Broadway version of his 1932 London revue, Words and Music).[67] Coward's last pre-war plays were This Happy Breed, a drama about a working-class family, and Present Laughter, a comic self-caricature with an egomaniac actor as the central character. These were first performed in 1942, although they were both written in 1939.[68]

Between 1929 and 1936 Coward recorded many of his best-known songs for His Master's Voice (HMV), now reissued on CD, including the romantic "I'll See You Again" from Bitter Sweet, the comic "Mad Dogs and Englishmen" from Words and Music, and "Mrs Worthington".[69]

Second World War

[edit]With the outbreak of the Second World War Coward abandoned the theatre and sought official war work. After running the British propaganda office in Paris, where he concluded that "if the policy of His Majesty's Government is to bore the Germans to death I don't think we have time",[70] he worked on behalf of British intelligence.[71] His task was to use his celebrity to influence American public and political opinion in favour of helping Britain.[n 6] He was frustrated by British press criticism of his foreign travel while his countrymen suffered at home, but he was unable to reveal that he was acting on behalf of the Secret Service.[73] In 1942 George VI wished to award Coward a knighthood for his efforts, but was dissuaded by Winston Churchill. Mindful of the public view of Coward's flamboyant lifestyle, Churchill used as his reason for withholding the honour Coward's £200 fine for contravening currency regulations in 1941.[73]

Had the Germans invaded Britain, Coward was scheduled to be arrested and killed, as he was in The Black Book along with other figures such as Virginia Woolf, Paul Robeson, Bertrand Russell, C. P. Snow and H. G. Wells. When this came to light after the war, Coward wrote: "If anyone had told me at that time I was high up on the Nazi blacklist, I should have laughed ... I remember Rebecca West, who was one of the many who shared the honour with me, sent me a telegram which read: 'My dear – the people we should have been seen dead with'."[74]

Churchill's view was that Coward would do more for the war effort by entertaining the troops and the home front than by intelligence work: "Go and sing to them when the guns are firing – that's your job!"[75] Coward, though disappointed, followed this advice. He toured, acted and sang indefatigably in Europe, Africa, Asia and America.[76] He wrote and recorded war-themed popular songs, including "London Pride" and "Don't Let's Be Beastly to the Germans". His London home was wrecked by German bombs in 1941, and he took up temporary residence at the Savoy Hotel.[77] During one air raid on the area around the Savoy he joined Carroll Gibbons and Judy Campbell in impromptu cabaret to distract the captive guests from their fears.[78] Another of Coward's wartime projects, as writer, star, composer and co-director (alongside David Lean), was the naval film drama In Which We Serve. The film was popular on both sides of the Atlantic, and he was awarded an honorary certificate of merit at the 1943 Academy Awards ceremony.[79] Coward played a naval captain, basing the character on his friend Lord Louis Mountbatten.[80] Lean went on to direct and adapt film versions of three Coward plays.[81]

Coward's most enduring work from the war years was the hugely successful black comedy Blithe Spirit (1941), about a novelist who researches the occult and hires a medium. A séance brings back the ghost of his first wife, causing havoc for the novelist and his second wife. With 1,997 consecutive performances, it broke box-office records for the run of a West End comedy, and was also produced on Broadway, where its original run was 650 performances.[n 7] The play was adapted into a 1945 film, directed by Lean. Coward toured during 1942 in Blithe Spirit, in rotation with his comedy Present Laughter and his working-class drama This Happy Breed.[84]

In his Middle East Diary Coward made several statements that offended many Americans. In particular, he commented that he was "less impressed by some of the mournful little Brooklyn boys lying there in tears amid the alien corn with nothing worse than a bullet wound in the leg or a fractured arm".[85][86] After protests from both The New York Times and The Washington Post, the Foreign Office urged Coward not to visit the United States in January 1945. He did not return to America again during the war. In the aftermath of the war, Coward wrote an alternative reality play, Peace in Our Time, depicting an England occupied by Nazi Germany.[59]

Post-war career

[edit]Coward's new plays after the war were moderately successful but failed to match the popularity of his pre-war hits.[87] Relative Values (1951) addresses the culture clash between an aristocratic English family and a Hollywood actress with matrimonial ambitions; South Sea Bubble (1951) is a political comedy set in a British colony; Quadrille (1952) is a drama about Victorian love and elopement; and Nude with Violin (1956, starring John Gielgud in London and Coward in New York) is a satire on modern art and critical pretension.[88] A revue, Sigh No More (1945), was a moderate success,[89] but two musicals, Pacific 1860 (1946), a lavish South Seas romance, and Ace of Clubs (1950), set in a night club, were financial failures.[90] Further blows in this period were the deaths of Coward's friends Charles Cochran and Gertrude Lawrence, in 1951 and 1952 respectively. Despite his disappointments, Coward maintained a high public profile; his performance as King Magnus in Shaw's The Apple Cart for the Coronation season of 1953, co-starring Margaret Leighton, received much coverage in the press,[91] and his cabaret act, honed during his wartime tours entertaining the troops, was a supreme success, first in London at the Café de Paris, and later in Las Vegas.[92] The theatre critic Kenneth Tynan wrote:

To see him whole, public and private personalities conjoined, you must see him in cabaret ... he padded down the celebrated stairs ... halted before the microphone on black-suede-clad feet, and, upraising both hands in a gesture of benediction, set about demonstrating how these things should be done. Baring his teeth as if unveiling some grotesque monument, and cooing like a baritone dove, he gave us "I'll See You Again" and the other bat's-wing melodies of his youth. Nothing he does on these occasions sounds strained or arid; his tanned, leathery face is still an enthusiast's.... If it is possible to romp fastidiously, that is what Coward does. He owes little to earlier wits, such as Wilde or Labouchere. Their best things need to be delivered slowly, even lazily. Coward's emerge with the staccato, blind impulsiveness of a machine-gun.[45]

In 1955 Coward's cabaret act at Las Vegas, recorded live for the gramophone and released as Noël Coward at Las Vegas,[93] was so successful that CBS engaged him to write and direct a series of three 90-minute television specials for the 1955–56 season. The first of these, Together With Music, paired Coward with Mary Martin, featuring him in many of the numbers from his Las Vegas act.[94] It was followed by productions of Blithe Spirit in which he starred with Claudette Colbert, Lauren Bacall and Mildred Natwick and This Happy Breed with Edna Best and Roger Moore. Despite excellent reviews, the audience viewing figures were moderate.[95]

During the 1950s and 1960s Coward continued to write musicals and plays. After the Ball, his 1953 adaptation of Lady Windermere's Fan, was the last musical he premiered in the West End; his last two musicals were first produced on Broadway. Sail Away (1961), set on a luxury cruise liner, was Coward's most successful post-war musical, with productions in America, Britain and Australia.[96] The Girl Who Came to Supper, a musical adaptation of The Sleeping Prince (1963), ran for only three months.[97] He directed the successful 1964 Broadway musical adaptation of Blithe Spirit, called High Spirits. Coward's late plays include a farce, Look After Lulu! (1959), and a tragi-comic study of old age, Waiting in the Wings (1960), both of which were successful despite "critical disdain".[98] Coward argued that the primary purpose of a play was to entertain, and he made no attempt at modernism, which he felt was boring to the audience although fascinating to the critics. His comic novel, Pomp and Circumstance (1960), about life in a tropical British colony, met with more critical success.[99][n 8]

Coward's final stage success came with Suite in Three Keys (1966), a trilogy set in a hotel penthouse suite. He wrote it as his swan song as a stage actor: "I would like to act once more before I fold my bedraggled wings."[101] The trilogy gained glowing reviews and did good box office business in the UK.[102] In one of the three plays, A Song at Twilight, Coward abandoned his customary reticence on the subject and played an explicitly homosexual character. The daring piece earned Coward new critical praise.[103] He intended to star in the trilogy on Broadway but was too ill to travel. Only two of the Suite in Three Keys plays were performed in New York, with the title changed to Noël Coward in Two Keys, starring Hume Cronyn.[104]

Coward won new popularity in several notable films later in his career, such as Around the World in 80 Days (1956), Our Man in Havana (1959), Bunny Lake Is Missing (1965), Boom! (1968) and The Italian Job (1969).[105] Stage and film opportunities he turned down in the 1950s included an invitation to compose a musical version of Pygmalion (two years before My Fair Lady was written), and offers of the roles of the king in the original stage production of The King and I, and Colonel Nicholson in the film The Bridge on the River Kwai.[106] Invited to play the title role in the 1962 film Dr. No, he replied, "No, no, no, a thousand times, no."[107] In the same year, he turned down the role of Humbert Humbert in Lolita, saying, "At my time of life the film story would be logical if the 12-year-old heroine was a sweet little old lady."[108]

In the mid-1960s and early 1970s successful productions of his 1920s and 1930s plays, and new revues celebrating his music, including Oh, Coward! on Broadway and Cowardy Custard in London, revived Coward's popularity and critical reputation. He dubbed this comeback "Dad's Renaissance".[109] It began with a hit 1963 revival of Private Lives in London and then New York.[110] Invited to direct Hay Fever with Edith Evans at the National Theatre, he wrote in 1964, "I am thrilled and flattered and frankly a little flabbergasted that the National Theatre should have had the curious perceptiveness to choose a very early play of mine and to give it a cast that could play the Albanian telephone directory."[111]

Other examples of "Dad's Renaissance" included a 1968 Off-Broadway production of Private Lives at the Theatre de Lys starring Elaine Stritch, Lee Bowman and Betsy von Furstenberg, and directed by Charles Nelson Reilly. Despite this impressive cast, Coward's popularity had risen so high that the theatre poster for the production used an Al Hirschfeld caricature of Coward (pictured above) [n 9] instead of an image of the production or its stars. The illustration captures how Coward's image had changed by the 1960s: he was no longer seen as the smooth 1930s sophisticate, but as the doyen of the theatre. As The New Statesman wrote in 1964, "Who would have thought the landmarks of the Sixties would include the emergence of Noël Coward as the grand old man of British drama? There he was one morning, flipping verbal tiddlywinks with reporters about "Dad's Renaissance"; the next he was ... beside Forster, T. S. Eliot and the OMs, demonstrably the greatest living English playwright."[112] Time wrote that "in the 60s... his best work, with its inspired inconsequentiality, seemed to exert not only a period charm but charm, period."[1]

Death and honours

[edit]

By the end of the 1960s, Coward developed arteriosclerosis and, during the run of Suite in Three Keys, struggled with bouts of memory loss.[113] This also affected his work in The Italian Job, and he retired from acting immediately afterwards.[114] Coward was knighted in 1970,[115] and was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.[116] He received a Tony Award for lifetime achievement in 1970.[117] In 1972, he was awarded an honorary Doctor of Letters degree by the University of Sussex.[118]

At the age of 73, Coward died at his home, Firefly Estate, in Jamaica on 26 March 1973 of heart failure[50] and was buried three days later on the brow of Firefly Hill, overlooking the north coast of the island.[119] A memorial service was held in St Martin-in-the-Fields in London on 29 May 1973, for which the Poet Laureate, John Betjeman, wrote and delivered a poem in Coward's honour,[n 10] John Gielgud and Laurence Olivier read verse, and Yehudi Menuhin played Bach. On 28 March 1984 a memorial stone was unveiled by the Queen Mother in Poets' Corner, Westminster Abbey. Thanked by Coward's partner, Graham Payn, for attending, the Queen Mother replied, "I came because he was my friend."[121]

The Noël Coward Theatre in St Martin's Lane, originally opened in 1903 as the New Theatre and later called the Albery, was renamed in his honour after extensive refurbishment, re-opening on 1 June 2006.[122] A statue of Coward by Angela Conner was unveiled by the Queen Mother in the foyer of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1998.[123] There are also sculptures of Coward displayed in New York and Jamaica,[124] and a bust of him in the library in Teddington, near where he was born.[125] In 2008 an exhibition devoted to Coward was mounted at the National Theatre in London.[126] The exhibition was later hosted by the Museum of Performance & Design in San Francisco and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Beverly Hills, California.[127] In June 2021 an exhibition celebrating Coward opened at the Guildhall Art Gallery in the City of London.[128]

Personal life

[edit]

Coward was homosexual but, following the convention of his times, this was never publicly mentioned.[60] The critic Kenneth Tynan's description in 1953 was close to an acknowledgment of Coward's sexuality: "Forty years ago he was Slightly in Peter Pan, and you might say that he has been wholly in Peter Pan ever since. No private considerations have been allowed to deflect the drive of his career; like Gielgud and Rattigan, like the late Ivor Novello, he is a congenital bachelor."[45] Coward firmly believed his private business was not for public discussion, considering "any sexual activities when over-advertised" to be tasteless.[129] Even in the 1960s, Coward refused to acknowledge his sexual orientation publicly, wryly observing, "There are still a few old ladies in Worthing who don't know."[130] Despite this reticence, he encouraged his secretary Cole Lesley to write a frank biography once Coward was safely dead.[131]

Coward's most important relationship, which began in the mid-1940s and lasted until his death, was with the South African stage and film actor Graham Payn.[132] Coward featured Payn in several of his London productions. Payn later co-edited with Sheridan Morley a collection of Coward's diaries, published in 1982. Coward's other relationships included the playwright Keith Winter, actors Louis Hayward and Alan Webb, his manager Jack Wilson and the composer Ned Rorem, who published details of their relationship in his diaries.[133] Coward had a 19-year friendship with Prince George, Duke of Kent, but biographers differ on whether it was platonic.[134] Payn believed that it was, although Coward reportedly admitted to the historian Michael Thornton that there had been "a little dalliance".[135] Coward said, on the duke's death, "I suddenly find that I loved him more than I knew."[136]

Coward maintained close friendships with many women, including the actress and author Esmé Wynne-Tyson, his first collaborator and constant correspondent; Gladys Calthrop, who designed sets and costumes for many of his works; his secretary and close confidante Lorn Loraine; the actresses Gertrude Lawrence, Joyce Carey and Judy Campbell; and "his loyal and lifelong amitié amoureuse", Marlene Dietrich.[137]

In his profession, Coward was widely admired and loved for his generosity and kindness to those who fell on hard times. Stories are told of the unobtrusive way in which he relieved the needs or paid the debts of old theatrical acquaintances who had no claim on him.[50] From 1934 until 1956, Coward was the president of the Actors Orphanage, which was supported by the theatrical industry. In that capacity, he befriended the young Peter Collinson, who was in the care of the orphanage. He became Collinson's godfather and helped him to get started in show business. When Collinson was a successful director, he invited Coward to play a role in The Italian Job. Graham Payn also played a small role in the film.[138]

In 1926, Coward acquired Goldenhurst Farm, in Aldington, Kent, making it his home for most of the next thirty years, except when the military used it during the Second World War.[139] It is a Grade II listed building.[140] In the 1950s, Coward left the UK for tax reasons, receiving harsh criticism in the press.[141] He first settled in Bermuda but later bought houses in Jamaica and Switzerland (Chalet Covar in the village of Les Avants, near Montreux), which remained his homes for the rest of his life.[142] His expatriate neighbours and friends included Joan Sutherland, David Niven, Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, and Julie Andrews and Blake Edwards in Switzerland[143] and Ian Fleming and his wife Ann in Jamaica. Coward was a witness at the Flemings' wedding, but his diaries record his exasperation with their constant bickering.[144]

Coward's political views were conservative, but not unswervingly so: he despised the government of Neville Chamberlain for its policy of appeasing Nazi Germany, and he differed sharply with Winston Churchill over the abdication crisis of 1936. Whereas Churchill supported Edward VIII's wish to marry "his cutie", Wallis Simpson, Coward thought the king irresponsible, telling Churchill, "England doesn't wish for a Queen Cutie."[145] Coward disliked propaganda in plays:

Nevertheless, his own views sometimes surfaced in his plays: both Cavalcade and This Happy Breed are, in the words of the playwright David Edgar, "overtly Conservative political plays written in the Brechtian epic manner."[147] In religion, Coward was agnostic. He wrote of his views, "Do I believe in God? I can't say No and I can't say Yes, To me it's anybody's guess."[148][n 11]

Coward spelled his first name with the diæresis ("I didn't put the dots over the 'e' in Noël. The language did. Otherwise it's not Noël but Nool!").[150] The press and many book publishers failed to follow suit, and his name was printed as 'Noel' in The Times, The Observer and other contemporary newspapers and books.[n 12]

Public image

[edit]

"Why", asked Coward, "am I always expected to wear a dressing-gown, smoke cigarettes in a long holder and say 'Darling, how wonderful'?"[152] The answer lay in Coward's assiduous cultivation of a carefully crafted image. As a suburban boy who had been taken up by the upper classes he rapidly acquired the taste for high life: "I am determined to travel through life first class."[153] He first wore a dressing gown onstage in The Vortex and used the fashion in several of his other famous plays, including Private Lives and Present Laughter.[154][155] George Walden identifies him as a modern dandy.[156] In connection with the National Theatre's 2008 exhibition, The Independent commented, "His famous silk, polka-dot dressing gown and elegant cigarette holder both seem to belong to another era. But 2008 is proving to be the year that Britain falls in love with Noël Coward all over again."[126]

As soon as he achieved success he began polishing the Coward image: an early press photograph showed him sitting up in bed holding a cigarette holder: "I looked like an advanced Chinese decadent in the last phases of dope."[157] Soon after that, Coward wrote:

He soon became more cautious about overdoing the flamboyance, advising Cecil Beaton to tone down his outfits: "It is important not to let the public have a loophole to lampoon you."[159] However, Coward was happy to generate publicity from his lifestyle.[160] In 1969 he told Time magazine, "I acted up like crazy. I did everything that was expected of me. Part of the job." Time concluded, "Coward's greatest single gift has not been writing or composing, not acting or directing, but projecting a sense of personal style, a combination of cheek and chic, pose and poise."[1]

Coward's distinctive clipped diction arose from his childhood: his mother was deaf and Coward developed his staccato style of speaking to make it easier for her to hear what he was saying; it also helped him eradicate a slight lisp.[161] His nickname, "The Master", "started as a joke and became true", according to Coward. It was used of him from the 1920s onwards.[151] Coward himself made light of it: when asked by a journalist why he was known as "The Master", he replied, "Oh, you know – Jack of all trades, master of none."[162] He could, however, joke about his own immodesty: "My sense of my importance to the world is relatively small. On the other hand, my sense of my own importance to myself is tremendous."[163] When a Time interviewer apologised, "I hope you haven't been bored having to go through all these interviews for your [70th] birthday, having to answer the same old questions about yourself", Coward rejoined, "Not at all. I'm fascinated by the subject."[1]

Works and appearances

[edit]Coward wrote more than 65 plays and musicals (not all produced or published) and appeared in approximately 70 stage productions.[164] More than 20 films were made from his plays and musicals, either by Coward or other screenwriters, and he acted in 17 films.[165]

Plays

[edit]In a 2005 survey Dan Rebellato divides the plays into early, middle and late periods.[166] In The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature (2006) Jean Chothia calls the plays of the 1920s and 1930s "the quintessential theatrical works of the years between World Wars I and II".[167] Rebellato considers Hay Fever (1925) typical of the early plays, "showing a highly theatrical family running rings around a group of staid outsiders"; Easy Virtue (1926) "brings the well-made play into the twentieth century".[166] Chothia writes that "the seeming triviality" and rich, flippant characters of Coward's plays, though popular with the public, aroused hostility from a few, such as the playwright Sean O'Casey, "perhaps particularly because of the ease with which his sexually charged writing seemed to elude censorship".[167] Rebellato rates Private Lives (1930) as the pinnacle of Coward's early plays, with its "evasion of moral judgement, and the blur of paradox and witticism".[166]

During the 1930s, once he was established by his early successes, Coward experimented with theatrical forms. The historical epic Cavalcade (1931) with its huge cast, and the cycle of ten short plays Tonight at 8.30 (1935), played to full houses, but are difficult to revive because of the expense and "logistical complexities" of staging them.[168] He continued to push the boundaries of social acceptability in the 1930s: Design for Living (1932), with its bisexual triangle, had to be premiered in the US, beyond the reach of the British censor.[167] Chothia comments that a feature of Coward's plays of the 1920s and 1930s is that, "unusually for the period, the women in Coward's plays are at least as self-assertive as the men, and as likely to seethe with desire or rage, so that courtship and the battle of the sexes is waged on strictly equal terms".[167][n 13]

The best-known plays of Coward's middle period, the late 1930s and the 1940s, Present Laughter, This Happy Breed and Blithe Spirit are more traditional in construction and less unconventional in content. Coward toured them throughout Britain during the Second World War, and the first and third of them are frequently revived in Britain and the US.[170]

Coward's plays from the late 1940s and early 1950s are generally seen as showing a decline in his theatrical flair. Morley comments, "The truth is that, although the theatrical and political world had changed considerably through the century for which he stood as an ineffably English icon, Noël himself changed very little."[171] Chothis comments, "sentimentality and nostalgia, often lurking but usually kept in check in earlier works, were cloyingly present in such post-World War II plays as Peace in Our Time and Nude with Violin, although his writing was back on form with the astringent Waiting in the Wings".[167] His final plays, in Suite in Three Keys (1966), were well received,[172] but the Coward plays most often revived are from the years 1925 to 1940: Hay Fever, Private Lives, Design for Living, Present Laughter and Blithe Spirit.[170]

Musicals and revues

[edit]Coward wrote the words and music for eight full-length musicals between 1928 and 1963. By far the most successful was the first, Bitter Sweet (1929), which he termed an operetta. It ran in the West End for 697 performances between 1929 and 1931.[173] Bitter Sweet was set in 19th-century Vienna and London; for his next musical, Conversation Piece (1934) Coward again chose a historical setting: Regency Brighton. Notices were excellent, but the run ended after 177 performances when the leading lady, Yvonne Printemps, had to leave the cast to honour a filming commitment. The show has a cast of more than fifty and has never been professionally revived in London.[174] A third musical with a historical setting, Operette, ran for 133 performances in 1938 and closed for lack of box-office business. Coward later described it as "over-written and under-composed", with too much plot and too few good numbers.[175] He persisted with a romantic historical theme with Pacific 1860 (1946), another work with a huge cast. It ran for 129 performances, and Coward's failure to keep up with public tastes was pointed up by the success of the Rodgers and Hammerstein show that followed Pacific 1860 at Drury Lane: Oklahoma! ran there for 1,534 performances.[82] His friend and biographer Cole Lesley wrote that although Coward admired Oklahoma! enormously, he "did not learn from it and the change it had brought about, that the songs should in some way further the storyline."[176] Lesley added that Coward compounded this error by managing "in every single show to write one song, nothing whatever to do with the plot, that was an absolute showstopper".[176]

With Ace of Clubs (1949) Coward sought to be up-to-date, with the setting of a contemporary Soho nightclub. It did better than its three predecessors, running for 211 performances, but Coward wrote, "I am furious about Ace of Clubs not being a real smash and I have come to the conclusion that if they don't care for first rate music, lyrics, dialogue and performance they can stuff it up their collective arses and go and see [Ivor Novello's] King's Rhapsody".[177] He reverted, without success, to a romantic historical setting for After the Ball (1954 – 188 performances). His last two musicals were premiered on Broadway rather than in London. Sail Away (1961) with a setting on a modern cruise ship ran for 167 performances in New York and then 252 in London.[178] For his last and least successful musical, Coward reverted to Ruritanian royalty in The Girl Who Came to Supper (1963), which closed after 112 performances in New York and has never been staged in London.[179]

Coward's first contributions to revue were in 1922, writing most of the songs and some of the sketches in André Charlot's London Calling!. This was before his first major success as a playwright and actor, in The Vortex, written the following year and staged in 1924. The revue contained only one song that features prominently in the Noël Coward Society's list of his most popular numbers – "Parisian Pierrot", sung by Gertrude Lawrence.[54] His other early revues, On With the Dance (1925) and This Year of Grace (1928) were liked by the press and public, and contained several songs that have remained well known, including "Dance, Little Lady", "Poor Little Rich Girl" and "A Room With a View".[54][180] Words and Music (1932) and its Broadway successor Set to Music (1939) included "Mad About the Boy", "Mad Dogs and Englishmen", "Marvellous Party" and "The Party's Over Now".[54]

At the end of the Second World War, Coward wrote his last original revue. He recalled "I had thought of a good title, Sigh No More, which later, I regret to say, turned out to be the best part of the revue".[181] It was a moderate success with 213 performances in 1945–46.[182] Among the best-known songs from the show are "I Wonder What Happened to Him?", "Matelot" and "Nina".[54] Towards the end of his life Coward was consulted about, but did not compile, two 1972 revues that were anthologies of his songs from the 1920s to the 1960s, Cowardy Custard in London (the title was chosen by Coward) and Oh, Coward! in New York, at the premiere of which he made his last public appearance.[183]

Songs

[edit]Coward wrote three hundred songs. The Noël Coward Society's website, drawing on performing statistics from the publishers and the Performing Rights Society, names "Mad About the Boy" (from Words and Music) as Coward's most popular song, followed, in order, by:

- "I'll See You Again" (Bitter Sweet)

- "Mad Dogs and Englishmen" (Words and Music)

- "If Love Were All" (Bitter Sweet)

- "Someday I'll Find You" (Private Lives)

- "I'll Follow My Secret Heart" (Conversation Piece)

- "London Pride" (1941)

- "A Room With a View" (This Year of Grace)

- "Mrs Worthington" (1934)

- "Poor Little Rich Girl" (On with the Dance)

- "The Stately Homes of England" (Operette)[54]

Coward was no fan of the works of Gilbert and Sullivan,[n 14] but as a songwriter was nevertheless strongly influenced by them. He recalled: "I was born into a generation that still took light music seriously. The lyrics and melodies of Gilbert and Sullivan were hummed and strummed into my consciousness at an early age. My father sang them, my mother played them ... my aunts and uncles, who were legion, sang them singly and in unison at the slightest provocation."[185] His colleague Terence Rattigan wrote that as a lyricist Coward was "the best of his kind since W. S. Gilbert."[186]

Critical reputation and legacy

[edit]The playwright John Osborne said, "Mr Coward is his own invention and contribution to this century. Anyone who cannot see that should keep well away from the theatre."[187] Tynan wrote in 1964, "Even the youngest of us will know, in fifty years' time, exactly what we mean by 'a very Noel Coward sort of person'."[45] In praise of Coward's versatility, Lord Mountbatten said, in a tribute on Coward's seventieth birthday:

Tynan's was the first generation of critics to realise that Coward's plays might enjoy more than ephemeral success. In the 1930s, Cyril Connolly wrote that they were "written in the most topical and perishable way imaginable, the cream in them turns sour overnight".[189] What seemed daring in the 1920s and 1930s came to seem old-fashioned in the 1950s, and Coward never repeated the success of his pre-war plays.[45] By the 1960s, critics began to note that underneath the witty dialogue and the Art Deco glamour of the inter-war years, Coward's best plays also dealt with recognisable people and familiar relationships, with an emotional depth and pathos that had been often overlooked.[190] By the time of his death, The Times was writing of him, "None of the great figures of the English theatre has been more versatile than he", and the paper ranked his plays in "the classical tradition of Congreve, Sheridan, Wilde and Shaw".[50] In late 1999 The Stage ran what it called a "millennium poll" of its readers to name the people from the world of theatre, variety, broadcasting or film who have most influenced the arts and entertainment in Britain: Shakespeare came first, followed by Coward in second place.[191]

A symposium published in 1999 to mark the centenary of Coward's birth listed some of his major productions scheduled for the year in Britain and North America, including Ace of Clubs, After the Ball, Blithe Spirit, Cavalcade, Easy Virtue, Hay Fever, Present Laughter, Private Lives, Sail Away, A Song at Twilight, The Young Idea and Waiting in the Wings, with stars including Lauren Bacall, Rosemary Harris, Ian McKellen, Corin Redgrave, Vanessa Redgrave and Elaine Stritch.[192] A centenary celebration was presented at the Savoy Theatre on 12 December 1999, devised by Hugh Wooldridge, featuring more than 30 leading performers, raising funds for the Actors' Orphanage.[193] Tim Rice said of Coward's songs, "The wit and wisdom of Noël Coward's lyrics will be as lively and contemporary in 100 years' time as they are today",[194] and many have been recorded by Damon Albarn, Ian Bostridge, The Divine Comedy, Elton John, Valerie Masterson, Paul McCartney, Michael Nyman, Pet Shop Boys, Vic Reeves, Sting, Joan Sutherland, Robbie Williams and others.[195]

Coward's music, writings, characteristic voice and style have been widely parodied and imitated, for instance in Monty Python,[196] Round the Horne,[197] and Privates on Parade.[198] Coward has frequently been depicted as a character in plays,[199][200] films, television and radio shows, for example, in the 1968 Julie Andrews film Star! (in which Coward was portrayed by his godson, Daniel Massey),[201] the BBC sitcom Goodnight Sweetheart[202] and a BBC Radio 4 series written by Marcy Kahan in which Coward was dramatised as a detective in Design For Murder (2000), A Bullet at Balmain's (2003) and Death at the Desert Inn (2005), and as a spy in Blithe Spy (2002) and Our Man in Jamaica (2007), with Malcolm Sinclair playing Coward in each.[203] On stage, characters based on Coward have included Beverly Carlton in the 1939 Broadway play The Man Who Came to Dinner.[204] A play about the friendship between Coward and Dietrich, called Lunch with Marlene, by Chris Burgess, ran at the New End Theatre in 2008. The second act presents a musical revue, including Coward songs such as "Don't Let's Be Beastly to the Germans".[205]

Coward was an early admirer of the plays of Harold Pinter and backed Pinter's film version of The Caretaker with a £1,000 investment.[206] Some critics have detected Coward's influence in Pinter's plays.[207] Tynan compared Pinter's "elliptical patter" to Coward's "stylised dialogue".[206] Pinter returned the compliment by directing the National Theatre's revival of Blithe Spirit in 1976.[208]

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

- ^ Violet's cousin, Rachel Veitch, was mother of Field-Marshal Douglas Haig.[3]

- ^ Evangeline Julia Marshall, an eccentric society hostess (1854–1944), married Clement Paston Astley Cooper, grandson of Sir Astley Paston Cooper, on 10 July 1877. She inherited Hambleton Hall from her brother Walter Marshall (d. 1899), and there she entertained rising talents in the artistic world, including Streatfeild, the conductor Malcolm Sargent and the writer Charles Scott Moncrieff, as well as the young Coward.[19]

- ^ Later known by her married name, Lorn Loraine.[25]

- ^ Coward himself acknowledged that Shaw's You Never Can Tell was the primary inspiration for The Young Idea.[42]

- ^ The cycle effectively comprised only nine plays: although Coward wrote ten works for the cycle, Star Chamber was dropped after a single performance.[65]

- ^ Harold Nicolson, speaking for the Ministry of Information, stated that Coward "possesses contacts with certain sections of opinion which are very difficult to reach through ordinary sources".[72]

- ^ The record (1,466 performances) had been held by Charley's Aunt since the 1890s.[82] Blithe Spirit's West End record was overtaken by Boeing Boeing in the 1960s.[83]

- ^ Coward's fictional South Sea Islands colony, "Samolo", was loosely based on Jamaica, where he had a home; he used it as the setting not only for his novel, but for two plays (Point Valaine and South Sea Bubble) and a musical (Pacific 1860).[100]

- ^ The caricature was also used in connection with other Coward works, for example on his album of his ballet suite, "London Morning" (1959; reissued in 1978 on LP on DRG SL 5180 OCLC 5966289 with the Hirschfeld drawing on the cover)

- ^ "We are all here today to thank the Lord for the life of Noel Coward.

Noel with two dots over the 'e'

And the firm decided downward stroke of the 'l'.

We can all see him in our mind's eye

And in our mind's ear

We can hear the clipped decided voice".[120] - ^ Coward also said, "I keep an open mind, but I will be somewhat surprised if St Peter taps me on the shoulder and says: 'This way, Noël Coward, come up and try your hand on the harp.' I am no harpist."[149]

- ^ Even Cole Lesley's 1976 biography refers to Coward as "Noel": "...I have also forgone the use of his beloved diaeresis over the 'e' in his name, having no wish to dizzy the eye of the reader."[151]

- ^ Others have interpreted Coward's strong female characters as evidence of misogyny.[169]

- ^ "I went to Iolanthe... beautifully done and the music lovely but dated. It's no use, I hate Gilbert and Sullivan".[184]

References

- ^ a b c d "Noel Coward at 70", Time, 26 December 1969, p. 46

- ^ Morley (1974), p. 2

- ^ Hoare, p. 2

- ^ Morley (1974), p. 3

- ^ Morley (1974), pp. 4, 8 and 67

- ^ Lesley, p. 19

- ^ Hoare, p. 19

- ^ "The Little Theatre", The Times, 28 January 1911, p. 12

- ^ Coward (Present Indicative), pp. 21–22

- ^ Hoare, pp. 23–26

- ^ a b "Garrick Theatre", The Times, 12 December 1912, p. 8

- ^ "The Savoy Theatre", The Times, 26 June 1912, p. 10; "The Coliseum", 29 October 1912, p. 8; and "Varieties etc", 18 November 1912, p. 1

- ^ "The Cult of Peter Pan", The Times, 24 December 1913, p. 8

- ^ "Fairies at the Garrick", The Times, 28 December 1915, p. 10

- ^ Castle, p. 12

- ^ Hoare, pp. 27, 30 and 51

- ^ a b "The Happy Family", The Times, 19 December 1916, p. 11

- ^ Hoare, pp. 33–34

- ^ Callow, Simon. "Englishman abroad", The Guardian, 19 April 2006, accessed 8 February 2009; and "History", Hambleton Hall website, accessed 8 February 2009

- ^ Hoare, pp. 39–43

- ^ Coward (Present Indicative), p. 66

- ^ Lesley, pp. 41–42

- ^ "Plays and Musicals" Archived 25 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Noel Coward Society, accessed 8 February 2009

- ^ Thaxter, John. "The Rat Trap" Archived 15 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine , British Theatre Guide, 2006, accessed 8 February 2009

- ^ Hoare, p. 79

- ^ Morley (1974), p. 52

- ^ a b Thaxter, John. I'll Leave It To You Archived 10 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine , British Theatre Guide, 2009

- ^ Cardus, Neville. "Gaiety Theatre", The Manchester Guardian, 4 May 1920, p. 13

- ^ Morley (1974), p. 57

- ^ Ervine, St John. "At the Play", The Observer, 25 July 1920, p. 9

- ^ "I'll Leave It to You", The Times, 22 July 1920, p. 10

- ^ Coward (Present Indicative), pp. 104–05 and 112

- ^ Castle, p. 38

- ^ "The Knight of the Burning Pestle", The Manchester Guardian, 25 November 1920, p. 14

- ^ "A Jacobean Romp", The Times, 25 November 1920, p. 10

- ^ Ervine, St John. "New Grand Guignol Series", The Observer, 4 June 1922, p. 9

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa. "Coward's long-lost satire was almost too 'daring' about women", The Observer, 16 September 2007, accessed 22 September 2016

- ^ Morley (1974), p. 66; and Lesley, p. 59

- ^ Hoare, pp. 89–91

- ^ "New Play at the Savoy", The Times, 2 February 1923, p. 8

- ^ "The Young Idea", The Observer, 4 February 1923, p. 11

- ^ Coward (Present Indicative), p. 114

- ^ Coward (Present Indicative), pp. 112 and 150

- ^ Hoare, p. 129

- ^ a b c d e Tynan, pp. 286–88

- ^ Coward (Present Indicative), pp. 182–85

- ^ Hoare, pp. 158; and Lesley, p. 257

- ^ "Fallen Angels", The Manchester Guardian, 23 April 1925, p. 12

- ^ Hoare, pp. 42–43

- ^ a b c d "Obituary: Sir Noel Coward", The Times, 27 March 1973, p. 18

- ^ Morley (1974), p. 107

- ^ Hoare, p. 169

- ^ Lesley, pp. 107–108

- ^ a b c d e f "Appendix 3 (The Relative Popularity of Coward's Works)", Noël Coward Music Index, accessed 29 November 2015

- ^ Richards, p. 56

- ^ Lesley, p. 112

- ^ Richards, p. 26

- ^ "Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1270 to the present", Measuring Worth website, accessed 21 September 2021

- ^ a b Lahr, p. 93

- ^ a b Norton, Richard C. "Coward & Novello", Operetta Research Center, 1 September 2007, accessed 29 November 2015

- ^ "Best Picture – 1932/33 (6th)" Archived 21 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, accessed 4 December 2013

- ^ Lesley, p. 134

- ^ Hoare, p. 249

- ^ Morley (1974), pp. 177 and 182

- ^ Hoare, pp. 268–70

- ^ Morley (1974), pp. 226–28 and 230

- ^ Morley (1974), pp. 237 and 239

- ^ Lahr, pp. 32 and 93

- ^ Naxos CDs 8.120559 OCLC 58787371 and 8.120623 OCLC 48993177

- ^ Richards, p. 105

- ^ Koch, Stephen. "The Playboy was a Spy", The New York Times, 13 April 2008, accessed 4 January 2009

- ^ Lesley, p. 215

- ^ a b Hastings, Chris. "Winston Churchill vetoed Coward knighthood", Telegraph.co.uk, 3 November 2007, accessed 4 January 2009

- ^ Coward (Future Indefinite), p. 121

- ^ Morley (1974), p. 246

- ^ "Light Entertainment", Time, 19 July 1954, accessed 4 January 2009

- ^ Hoare, p. 317

- ^ Hoare, p. 318

- ^ "In Which we Serve" Archived 5 December 2013 at archive.today , Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, accessed 5 December 2013

- ^ Hoare, pp. 322–323

- ^ Mander and Mitchenson, pp. 317, 365 and 377

- ^ a b Gaye, p. 1525

- ^ Herbert, p. 1280

- ^ Hoare, p. 331

- ^ Calder, Robert. Beware the British serpent, p. 103

- ^ Hoare, p. 341

- ^ Lahr, p. 136

- ^ Lesley, pp. 314, 370 and 361

- ^ Morley (1974), p. 308

- ^ Lesley, pp. 248 and 289

- ^ "Haymarket Theatre", The Times, 8 May 1953, p. 12; and Brown, Ivor. "Royal and Ancient", The Manchester Guardian, 8 May 1953, p. 5

- ^ Morley (1974), pp. 339–40

- ^ Reissued in 2003 on CD by CBS – DRG 19037

- ^ Mander and Mitchenson, pp. 547–548

- ^ Payn and Morley (1974), pp. 287–88, 304 and 314

- ^ Lesley, pp. 410–14, and 428–29

- ^ Lesley, p. 430

- ^ Simon, John. "Waiting in the Wings", The NY Magazine, 3 January 2000, accessed 8 February 2009

- ^ Payn and Morley, pp. 451 and 453

- ^ Coward, Plays, Six, p. xi

- ^ Coward, Plays, Five, introduction, unnumbered page

- ^ Morley (1974), p. 375

- ^ "Noel Coward's Skeleton Feast", The Times, 15 April 1966, p. 16

- ^ Hoare, p. 502

- ^ Hoare, pp. 380, 414, 491, 507 and 508

- ^ Hoare, pp. 387, 386, and 473

- ^ Day, p. 310

- ^ Richards, p. 83

- ^ Hoare p. 479 et seq.

- ^ Morley (1974), pp. 370–72

- ^ Morley (1974), p. 369

- ^ Ronald Bryden in The New Statesman, August 1964, quoted in Hoare, p. 479

- ^ Hoare, p. 501

- ^ Lesley, p. 454

- ^ "No. 45036". The London Gazette (Supplement). 6 February 1970.

- ^ "Coward, Sir Noël", Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edition, Oxford University Press, December 2007, accessed 12 March 2009.

- ^ "Chronology" Archived 13 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Noël Coward Society, May 2001, accessed 27 August 2008

- ^ "List of Honorary Graduates" Archived 19 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, University of Sussex, accessed 17 December 2014

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2. McFarland & Company (2016) ISBN 0786479922

- ^ Lesley, p. 481

- ^ Day, p. 725

- ^ Davies, Hugh. "Coward is the toast of theatreland again", The Daily Telegraph, 1 July 2006, p. 14

- ^ "Coward statue unveiled", BBC news, 8 December 1998, accessed 8 February 2009

- ^ "Centenary Year – 1999" Archived 9 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, The Noël Coward Society, accessed 10 March 2009 and Koss, p. 163

- ^ Historic England, "Teddington Library (1396400)", National Heritage List for England, accessed 3 July 2014

- ^ a b Byrne, Ciar. "What's inspiring the Noël Coward renaissance?" The Independent, 21 January 2008, accessed on 17 March 2009

- ^ "Coward on the Coast", The Noël Coward Society, 27 November 2009

- ^ "Noel Coward – Art and Style" Archived 20 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Guildhall Art Gallery. Retrieved 20 September 2021

- ^ Payn, p. 248

- ^ Hoare, p. 509

- ^ Lesley, p. xvii

- ^ Payn, passim

- ^ Hoare, pp. 162–63, 258, 261–62, 275, 273–74, and 469–70

- ^ Hoare, p. 122

- ^ "Upstairs life of a royal rogue", The Daily Express, 26 February 2012

- ^ Lesley, p. 231

- ^ Lesley, p. 176

- ^ Payn and Morley, p. 668

- ^ Clark, Ross. "Mad about the house", The Telegraph, 24 November 2004, accessed 27 August 2016

- ^ Historic England, "Goldenhurst Manor (1071221)", National Heritage List for England, accessed 24 August 2016

- ^ Lesley, p. 355

- ^ Lesley, p. 395

- ^ Lesley, p. 437

- ^ Lesley, p. 310; and Payn and Morley, p. 463

- ^ Lesley, pp. 187 and 197

- ^ Morley (1974), p. 249

- ^ Kaplan, p. 4

- ^ Coward (Not Yet the Dodo), p. 54.

- ^ Richards, pp. 64–65

- ^ Richards, p. 58

- ^ a b Lesley, p. xx

- ^ Richards, p. 59

- ^ Richards, p. 28

- ^ Sacheli, Robert. "Joyeux Noel", Dandyism.net, 16 December 2006, accessed 17 March 2009

- ^ Private Lives, Act II, passim

- ^ Barbey D'Aurevilly, p. 45

- ^ Castle, p. 66

- ^ Coward (Present Indicative), p. 183

- ^ Hoare, p. 201

- ^ Morley, p. 82

- ^ Hoare, p. 16

- ^ Richards, p. 65

- ^ Richards, p. 67

- ^ Mander and Mitchenson, passim

- ^ Contemporary Authors Online, Thomson Gale, 2004, accessed 30 December 2008: requires subscription; and Noel Coward at the IMDB database, accessed 12 March 2009

- ^ a b c Rebellato, Dan. "Coward, Noël", The Oxford Encyclopedia of Theatre and Performance, Oxford University Press, 2005. Retrieved 5 April 2020 (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e Chothia, Jean. "Coward, Noël", The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature, Oxford University Press, 2006. Retrieved 5 April 2020 (subscription required)

- ^ Morgan, Terry. "Tonight at 8.30", Variety, 5 November 2007

- ^ Billington, Michael. "Tonight at 8.30 review – unexpectedly nourishing Noel Coward marathon" and " The play's the thing in a fine Noël Coward revival", The Guardian 11 March 2014 and 11 May 2014

- ^ a b "Productions" Archived 5 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Noël Coward. Retrieved 5 April 2020

- ^ Morley, Sheridan. "Noël Coward", Noël Coward. Retrieved 5 April 2020

- ^ Bryden, Ronald. "Theatre", The Observer, 1 May 1966, p. 24

- ^ Mander and Mitchenson, p. 183; and Gaye, p. 1529

- ^ Mander and Mitchenson, pp. 270–271

- ^ Mander and Mitchenson, pp. 326 and 336–337

- ^ a b Lesley, p. 196

- ^ Lesley, p. 291

- ^ Mander and Mitchenson, p. 489; and Gaye, p. 1537

- ^ Mander and Mitchenson, pp. 500 and 510

- ^ Mander and Mitchenson, pp. 128 and 171

- ^ Quoted in Morley (2004), p. 91

- ^ Mander and Mitchenson, p. 378

- ^ Lesley, pp. 469 and 471

- ^ Day, p. 125

- ^ Programme note for Cowardy Custard (1972) quoting The Noël Coward Song Book

- ^ Day, p. 257

- ^ "Noel Coward", Introduction page to NoelCoward.com, accessed 8 February 2009

- ^ Day, p. 3

- ^ Lahr, p. 2

- ^ Kaplan, pp. 7–13

- ^ "And the winner is ...", The Stage, 6 January 2000, p. 11

- ^ Kaplan, pp. 217–21

- ^ "Noël Coward: The Centenary Celebration", The Stage, 18 November 1999, p. 15

- ^ "Music", Noël Coward Archive Trust, accessed 21 September 2021

- ^ "Twentieth-century blues: the songs of Noel Coward", "Ian Bostridge: Noël Coward songbook"; and "Sutherland sings Noel Coward", WorldCat, accessed 5 December 2013

- ^ McCall, p. 145

- ^ Dibbs, p. 245

- ^ Nichols, Peter: Privates on Parade, Act 2, Scene 1 ("Noël, Noël")

- ^ Hoare, Philip. "Manuscripts and the Master", The Daily Telegraph, 22 May 2005 (subscription required)

- ^ Martin, Dominic. Making Dickie Happy, TheStage.co.uk., 27 September 2004, accessed 4 January 2009

- ^ "Star! (1968)" Time Out Film Guide, accessed 16 February 2009

- ^ Grove, Valerie, "Carrying on Kenneth's pain", The Times, 27 December 1997, p. 19 and "Book Now" The Independent, 20 August 2008, p. 16

- ^ "Audio and Broadcasts" Archived 22 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, The Noël Coward Society, 2007, accessed 11 March 2009

- ^ Isherwood, Charles. "The Man Who Came to Dinner", Variety, 28 July 2000, accessed 16 February 2009

- ^ Vale, Paul. "Lunch with Marlene", The Stage, 9 April 2008, accessed 29 March 2010

- ^ a b Hoare, p. 458

- ^ Hoare, p. 269

- ^ "Blithe Spirit by Noel Coward, The National Theatre, June 1976 (and tour)" at haroldpinter.org, 2003, accessed 7 March 2009

Sources

[edit]- Barbey D'Aurevilly, Jules (2002) [1845]. Who's a Dandy? – Dandyism and Beau Brummell. George Walden (trans. and ed. of new edition). London: Gibson Square. ISBN 978-1-903933-18-3.

- Castle, Charles (1972). Noël. London: W H Allen. ISBN 978-0-491-00534-0.

- Coward, Noël (1994). Plays, Five. Sheridan Morley (introduction). London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-413-51740-1.

- Coward, Noël (1994). Plays, Six. Sheridan Morley (introduction). London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-413-73410-5.

- Coward, Noël (2004) [1932]. Present Indicative – Autobiography to 1931. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-413-77413-2.

- Coward, Noël (1954). Future Indefinite. London: Heinemann. OCLC 5002107.

- Coward, Noël (1967). Not Yet the Dodo, and other verses. London: Heinemann. OCLC 488338862.

- Day, Barry, ed. (2007). The Letters of Noël Coward. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-1-4081-0675-4.

- Dibbs, Martin (2019). Radio Fun and the BBC Variety Department, 1922–67. Cham: Springer.

- Gaye, Freda, ed. (1967). Who's Who in the Theatre (fourteenth ed.). London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons. OCLC 5997224.

- Herbert, Ian, ed. (1977). Who's Who in the Theatre (sixteenth ed.). London and Detroit: Pitman Publishing and Gale Research. ISBN 978-0-273-00163-8.

- Hoare, Philip (1995). Noël Coward, A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson. ISBN 978-1-4081-0675-4.

- Kaplan, Joel; Stowel, Sheila, eds. (2000). Look Back in Pleasure: Noël Coward Reconsidered. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-413-75500-1.

- Koss, Richard (2008). Jamaica. London: Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-693-9.

- Lahr, John (1982). Coward the Playwright. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-413-48050-7.

- Lesley, Cole (1976). The Life of Noël Coward. London: Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-01288-1.

- Mander, Raymond; Mitchenson, Joe; Day, Barry; Morley, Sheridan (2000) [1957]. Theatrical Companion to Coward (second ed.). London: Oberon. ISBN 978-1-84002-054-0.

- McCall, Douglas (2014). Monty Python: A Chronology, 1969–2012. Jefferson: Mc Farland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7811-8.

- Morley, Sheridan (1974) [1969]. A Talent to Amuse. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-003863-7.

- Morley, Sheridan (2005). Noël Coward. London: Haus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-90-434188-8.

- Payn, Graham; Morley, Sheridan, eds. (1982). The Noël Coward Diaries (1941–1969). London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-297-78142-4.

- Payn, Graham (1994). My Life with Noël Coward. New York: Applause Books. ISBN 978-1-55783-190-3.

- Richards, Dick, ed. (1970). The Wit of Noël Coward. London: Sphere Books. ISBN 978-0-7221-3676-8.

- Tynan, Kenneth (1964). Tynan on Theatre. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin. OCLC 949598.

Further reading

[edit]- Braybrooke, Patrick (1933). The Amazing Mr Noel Coward. Denis Archer. OCLC 1374995.

- Coward, Noël (1985). The Complete Stories. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-413-59970-4.

- Coward, Noël (1986). Past Conditional (third volume, unfinished, of autobiography). London: Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-413-60660-0.

- Coward, Noël (1944). Middle East Diary. London: Heinemann. OCLC 640033606.

- Coward, Noël (1998). Barry Day (ed.). Coward: The Complete Lyrics. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-413-73230-9.

- Coward, Noël (2011). Barry Day (ed.). The Complete Verse of Noël Coward. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-1-4081-3174-9.

- Fisher, Clive (1992). Noël Coward. London: Weidenfeld. ISBN 978-0-297-81180-0.

- James, Elliot (2020). The Importance of Happiness: Noël Coward and the Actors' Orphanage. UK: Troubador Publishing. ISBN 9781800460416.

- Wynne-Tyson, Jon (2004). Finding the Words: A Publishing Life. Norwich: Michael Russell. ISBN 978-0-85955-287-5.

External links

[edit]| Archives at | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| How to use archival material |

Works

- Works by Noel Coward at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Noël Coward at the Internet Archive

- Works by Noël Coward at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Portals

- Noël Coward

- 1899 births

- 1973 deaths

- 20th-century English dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century English LGBTQ people

- 20th-century English male actors

- 20th-century English male singers

- 20th-century English memoirists

- 20th-century English screenwriters

- Academy Honorary Award recipients

- Actors awarded knighthoods

- Actors from the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

- Algonquin Round Table

- Alumni of the Italia Conti Academy of Theatre Arts

- Artists' Rifles soldiers

- British Army personnel of World War I

- British LGBTQ film directors

- Cabaret singers

- Composers awarded knighthoods

- English expatriates in Jamaica

- English expatriates in Switzerland

- English gay actors

- English gay musicians

- English gay writers

- English LGBTQ composers

- English LGBTQ dramatists and playwrights

- English LGBTQ screenwriters

- English LGBTQ singers

- English LGBTQ songwriters

- English lyricists

- English male composers

- English male dramatists and playwrights

- English male film actors

- English male pianists

- English male screenwriters

- English male songwriters

- English male stage actors

- English musical theatre composers

- English pianists

- Gay composers

- Gay dramatists and playwrights

- Gay memoirists

- Gay screenwriters

- Gay singers

- Gay songwriters

- Knights Bachelor

- LGBTQ theatre directors

- MI5 personnel

- Military personnel from the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

- People from Teddington

- Singers awarded knighthoods

- Singers from the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

- Special Tony Award recipients